|

1971 was a good year for giallo cinema. The Wikipedia page for this distinctively Italian subgenre of the thriller lists 31 such films released in that year alone, including a fair few fan favourites. These include: Lucio Fulci’s A Lizard in a Woman's Skin [Una lucertola con la pelle di donna]; Umberto Lenzi’s Oasis of Fear [Un posto ideale per uccidere]; the Dario Argento double of The Cat o' Nine Tails [Il gatto a nove code] and Four Flies on Grey Velvet [4 mosche di velluto grigio]; Duccio Tessari’s The Bloodstained Butterfly [Una farfalla con le ali insanguinate]; Mario Bava’s A Bay of Blood [Reazione a catena]; and Emilio Miraglia’s The Night Evelyn Came Out of the Grave [a notte che Evelyn uscì dalla tomba]. Released the same year was Cold Eyes of Fear [Gli occhi freddi della paura], a film that at first glance does appear to be a product of this then hugely popular subgenre. An Italian-Spanish co-production directed by Italian action specialist Enzo G. Castellari, it has music by the great Ennio Morricone, whose giallo scores include two of the above-listed films, and was edited by Vincenzo Tomassi, who the same year worked with Morricone on A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin, one of several movies he cut for cult horror filmmaker Lucio Fulci. And of course, there’s that title, which for my money has giallo potential written all over it.

If this doesn’t help to convince a newcomer that Cold Eyes of Fear is a giallo thriller – and I should note that it is included on that above-mentioned Wikipedia list – then the scene that begins the film after the opening titles have concluded (more on them in a minute) would seem to confirm it. An attractive woman (Karyn Schubert) strips down to her lacy black nightdress in a darkened bedroom, and as she walks over to a mirror to admire her body, a hand comes into shot in massive close-up and clicks open a switchblade knife. In a series of quick disorientating cuts, the woman looks every which way before settling her gaze on the male figure holding the weapon and advancing slowly towards her. An intimidating bark from the man startles the woman so much that she falls back on her bed, and the man then grasps her wrist and slowly trails the knife over her chest and neck in the sort of phallic weapon statement of sexualised violent intent that would have been banned in the UK a few years ago, and probably still prompts stern looks from BBFC censors today. It doesn’t end there. When the man cuts through one of the staps of the nightdress, the woman attempts to flee but falls to the floor, and as she backs off in terror, the man pulls off her nightdress to leave her in her underwear, which he then also then cuts off with his knife. As the woman lays naked on her bed, the now equally naked man starts tenderly kissing and fondling her body in a curiously tender-seeming overture to rape, one that, rather worrying, the woman appears to be responding positively to. As she pulls the man towards her, however, she reaches down with her free hand and picks up the dropped knife, which she uses to stab her attacker in the back. A classic giallo opening, right? Well, not quite. As soon as the man is stabbed, the camera zooms out and a watching audience applauds what is revealed to be a nightclub show staged for horny patrons in search of a bit of staged pre-internet sex and violence. It’s a neat bit of deception that also sends a message to the viewer that all here is not going to be quite what it seems, and that the giallo that we may have thought we were watching is soon to be revealed to be something else entirely.

Even before we reach this point, the film has indicated that it’s not going to go the way of a regular giallo with a title sequence that plays over footage of an as-yet unidentified man driving not through the expected Italian city streets or countryside, but seedy old early-1970s London, the city in which the entire film is set and where the giallo-show nightclub is apparently located. Sat uncomfortably at one of its tables is attractive Italian sex worker Anna (Giovanna Ralli), who has somehow hooked up with a drunken local man and is now looking for a way to ditch him and take her leave. As the show concludes, she catches the eye of handsome solicitor Peter Bedell (Gianni Garko) who is drinking at the bar and who responds her ‘please rescue me’ look by making a show of accidentally spilling his drink on her dress (“Idiot! I paid £35 for this!”) and politely leading her off to get some water to clean it. Unsurprisingly, the two immediately exit the bar, and are long gone by the time the drunken man emerges to pester a good-humouredly patient policeman about his mysteriously vanished date.

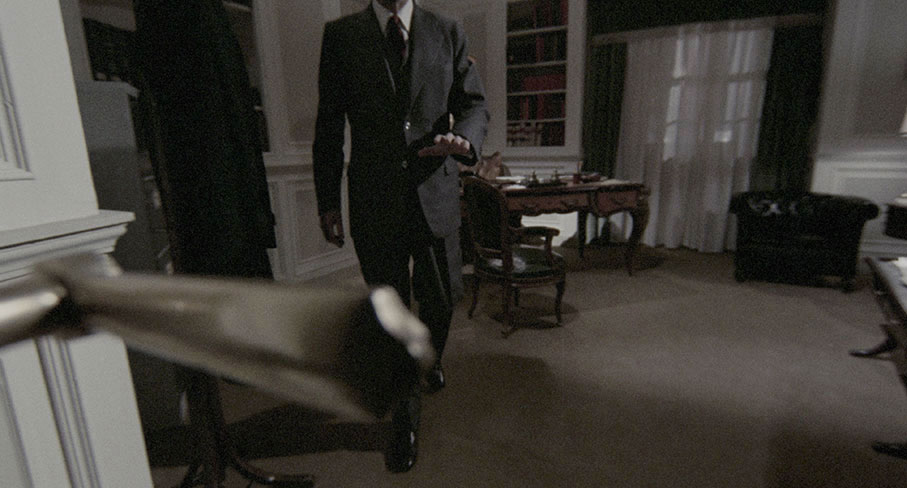

What follows is visually lively sequence that has also become bit of a time-capsule, as the Peter and Anna trip around Central London locations in a ‘let’s have fun’ montage that appears to have been improvised on the hoof and was clearly shot guerrilla-style with a handheld camera and no formal permission. This gives the sequence an air of documentary realism, which is enhanced by the camera operator having to react suddenly to whatever the actors choose to do, and the passers-by who turn to look at either the couple or the camera. It concludes with Peter making a phone call to the house owned by his uncle, Judge Bedell (Fernando Rey), to convince his uncle’s butler Hawkins (Leonardo Scavino) to disappear for the evening so he can have the place to himself. The judge is working late tonight, he assures him, so he won’t be any the wiser. No sooner has Hawkins put the phone down, however, the door opens and an unidentified figure walks slowly in, and whoever it is, he clearly alarms the hell out of poor Hawkins.

A short while later, Peter and Anna arrive at the house, and Peter has to bumble around to find the door he has a key for, and as soon as they get inside, he demonstrates to Anna what an entitled pig he is by forcibly kissing her against her will. She fights him off and quickly recovers, then flashes Peter a seductive smile, not the best way to discourage this one. As Anna walks through the house, however, a door eases quietly open, and whoever it was that gave Watkins such a start is shown now watching Peter and Anna from the shadows. While this also has a whiff of giallo cinema about it, that aspect is neutered a little by the fact that we can clearly see the intruder’s face. A fake jump-scare later, Peter once again tries to force himself on Anna, who throws him to the floor, then less than a minute later is willingly letting him kiss and fondle her, while Peter quietly pushes her to reveal how to say “love whore” in Italian. What an absolute charmer. They’re just getting down to business – a sequence visually enlivened by the hanging ceiling light that Peter accidentally knocks and which then swings back and forth – when the body of the now deceased Hawkins falls out of the cupboard in traditional murder-mystery manner. Anna screams and runs from the room with Peter in hot pursuit, and in one of my favourite shots in the film, the camera circles ominously round the terrified and transfixed Anna to reveal the pistol-packing, leather-jacketed intruder we can presume was responsible for Hawkins’ death. Editor Tomassi then cuts rapidly between zoom-in shots of the faces and eyes of the three individuals and the barrel of the intruder’s gun, giving the moment the air of a spaghetti western stand-off. Peter does the traditional “there’s no money – take the silver – I don’t want any trouble” bit as the intruder wanders over to Anna to compliment her on her work. Instead of then assaulting her as expected, he orders them both to sit down, and it becomes quickly evident that Cold Eyes of Fear is no giallo in the traditional sense, but a home invasion thriller. Quite what the intruder wants, what Peter and Anna will do, and what fate awaits them is at the core of the story that subsequently unfolds.

If I’m going to continue – and I am – then I can’t avoid dropping a few small plot spoilers, so please proceed with caution or skip to final paragraph (which you can do automatically by clicking here) if you’ve yet to see the film and intend to do so.

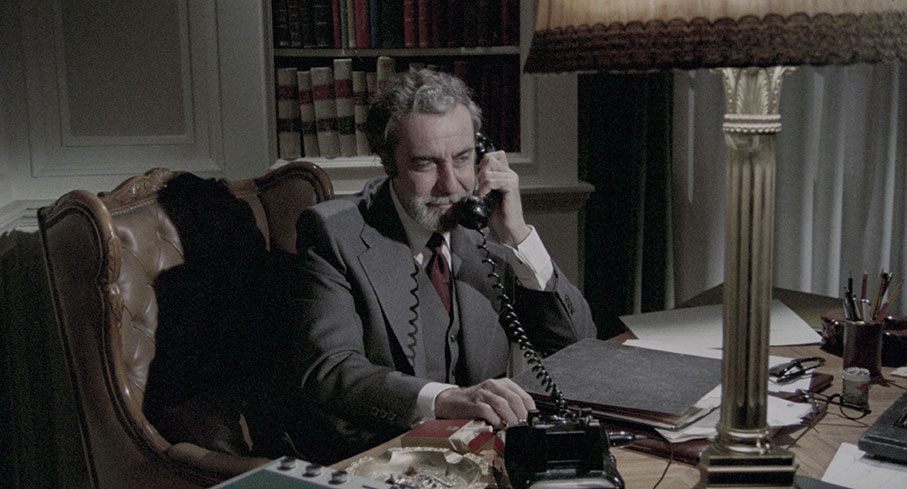

The intruder’s name is Quill (Julián Mateos), and all he initially tells Peter and Anna is that they are required to wait, but not what for. A potential complication arrives in the shape of a call from Peter’s uncle, who is still in his chambers at the court under police guard, where he is going through new evidence for a case over which he is presiding in the morning. Oddly, he doesn’t seem surprised that Peter’s in the house, and seems to know full well that he has a woman with him, despite Peter’s weakly unconvincing denial, and asks him to find some documents he needs for the case and to call him back when he finds them.

By this point it seemed clear to me that Quill’s arrival had something to do with the judge and the case he is soon to hear (“It appears there was an eyewitness after all,” the judge tells Peter while Quill listens in), but again, this proves to be only partially true. What happens next did confuse me a little. The judge writes a note that he gives to one of his police guards to deliver to Peter by hand, and the moment we get out first good look at the cop in question, it seemed obvious to me that he was in league with Quill. The thing is, it’s not because of anything he says, but because of how he’s lit by cinematographer Antonio L. Ballesteros, who casts the entire top half of his face into shadow in a manner that seems to paint him visually as a bad guy. Yet a short while later, when he turns up at door of the house in which Peter and Anna are being held, the impression we’re given is that he’s the real deal. Indeed, Quill orders Peter to deal with this unwelcome and potentially problematic visitor, and threatens to kill them all if he doesn’t. Peter does as he’s told, making a loud show of conversing innocently with the policeman whilst simultaneously whispering warnings to him about the presence of Quill. The cop responds by punching him in the mouth so hard that I genuinely winced. So was this meant to be the moment we discover that this is not a real cop at all but Quill’s partner-in-crime? It certainly plays that way, but I’d already made that assumption back in the judge’s chamber. Either way, it’s still an ultimately satisfying twist that introduces Peter and Anna and us to the film’s principal antagonist, Arthur Welt (Frank Wolff), who has effectively conned Quill into helping him with a made-up story about a safe full of money that they are ostensibly going to the house to rob. But Welt has a very personal reason for this home invasion, one that over the course of the film’s second half makes us realise that the real bad guy here is not Welt or Quill, but the man sitting in his chambers under police guard.

It's an intriguing setup for a film peppered with neat moments, smartly handled sequences, and interesting and socially relevant plot twists, as well as a final scene that I’m not about to reveal but whose socio-political subtext I’m convinced could write a couple of weighty paragraphs about alone. Castellari directs with style and the occasional giallo-esque flourish, framing a door handle that may prove deadly to turn and the figure about to approach it in the same deep focus extreme wide shot, and filming Anna’s eyes as she attempts to make a surreptitious phone call through the holes in the quietly rotating telephone dial. Later, there’s even a trippy paranoia-driven hallucination, a borderline bonkers sequence that sees Castellari momentarily throw all caution to the wind.

To really appreciate all this, however, you’re going to have to overcome a small but initially distracting obstacle. The film is set in London and the actors are all clearly delivering their lines in English, which is completely appropriate for the setting and the characters. With the exception of American-born Frank Wolff, however, all of the actors are either Italian or Spanish and very probably delivered their lines with accents that clearly indicated their country of birth. To get around this, English actors were thus hired to dub their voices, and while post-dubbing dialogue was common practice for Italian genre cinema of the day, a couple of the replacements here really do jar.

First the good news. I’m not sure if Giovanna Ralli dubbed her own voice as Anna, but it certainly plays that way, and as Anna is an Italian working abroad, her accent is appropriate and she ends up being the most vocally convincing. Whoever is responsible for Arthur’s English voice (maybe Frank Wolff himself?) also does a decent job, and for the most part Peter is believable in his annoyingly upper-middle class way. But then there’s Quill, who when he first speaks sounds as if he’s been dubbed by someone trying to do a wideboy cockney take on Melvin Hayes, and whose vocal pitch and inflection is a complete mismatch for this character and how he’s played by Spanish actor Julián Mateos. And then have the divine Fernando Rey, who has been saddled with a pompously posh English whose delivery at times sounds like an elocution lesson for slow beginners. The voices on the Italian dub are certainly better suited to both of these characters, but as the original actors clearly delivered their lines in English, the sometimes obvious mismatch of dialogue to mouths on that version creates its own distraction issues.

So is this a problem? Well, initially yes, but ultimately no. As I noted above, post-dubbing films was common practice in Italian cinema of the day, and is thus something most consumers of international cinema have long since learned to live with. Anyone here unable to watch A Fistful of Dollars because of the English dubbing of the supporting characters? I thought not. And for the most part, the dubbing here is not bad at all, which is probably why those two voices tend to jar so much when their characters first open their mouths. But here’s the thing, by midway through the second half I’d become so involved in the drama that I ceased to care a hoot about Quill’s squeaky geezer voice and had come to accept that this was just how he spoke. And put aside these mismatched voices and the performances here are of a generally high calibre, and what the actors do with facial expressions often says more than dialogue – surprisingly localised dialogue I might add – that probably did not feel natural for them to deliver. In this respect, director Castellari, cinematographer Ballesteros and editor Tomassi make good on the film’s title by focussing on the eyes and faces of characters as they react in fear or anger, size up the situation, or subtly send messages to each to suggest a possible next move.

Sitting just beneath the surface there’s also an intriguing class-conflict subtext, one that sees Arthur moved from one position on the social scale to another over the course of the drama, as surface of the person he initially presents himself to be is peeled back to reveal the man he really is and until a few years ago was, and why he has specifically targeted this house. There’s also a subtle suggestion that there might be more than a business relationship between Arthur and Quill – certainly Quill shows no interest in Anna, even when she strips before him in the bathroom and attempts to seduce him, a move he brusquely and almost angrily rejects. As all this unfolds, I found myself gradually sympathising more with Arthur than Peter, whose pushy attempts to force himself onto Anna made him difficult to like from the off, though an explanation for his sense of self-entitlement comes a little later when he reveals that he was educated at Eton. I even found myself slowly warming to Quill, who discovers too late that he's been played and at one point is beaten silly by a suddenly energised and furious Peter, a pasting that the watching Arthur curiously allows to continue until it looks like Peter might actually kill the young intruder.

The sometimes iffy voice dubbing aside, there are some elements of Cold Eyes of Fear that don’t quite click, most – though not all – of which are highlighted in the commentary track. In the end, however, these small logic blips do not seriously harm what for the most is part a neatly developed, claustrophobic, and character-centric thriller that makes effective use of the interior location to which the majority of the drama is confined. Thanks in part to this and the London setting, there’s an Armchair Theatre feel to the setup and how the story subsequently unfolds, and even how it concludes. Nailing it to its time is an almost avant-garde improvised jazz score by the great Ennio Morricone (for those wondering how you compose an improvised score, this is covered briefly in the special features), which contributes to the sense of encroaching madness but is wisely and effectively put on hold for the tensely handled in-the-dark finale. The result is a curious but oddly fascinating and often stylishly executed work that I found myself increasingly warming to as it progressed, an appreciation that increased over the course of my second and third viewings. Given how good the performances are on a visual level, however, I did find myself secretly pining for the version that never was and never will be, one in which the actors all delivered their own lines in their own voices, and incongruity of accents be damned.

Cold Eyes of Fear has been released by Indicator simultaneously on Blu-ray and UHD, and it’s the UHD under examination here. The transfer has been sourced from a brand-new 4K restoration from the original negative by Powerhouse Films and is presented here in its original 1.85:1 aspect ratio in a resolution of 2160p and Dolby Vision HDR, though the disc is also HDR-10 compatible.

So how do I put into coherent words what I really liked about this transfer? Let’s start with on-the-move title sequence and the verité footage of Peter and Anna tripping around Central London that follows shortly after. The image here may often be shy of pin-sharp and detail sometimes indistinct, but oh, the texture. We’ve rattled on before on this site about the unique feel that film still has when compared to even the most pristine digital picture, and that’s evident aplenty in this opening sequence, where the image has such a tactile feel that I wanted to reach into the screen and grab hold of it. There’s something heart-warmingly nostalgic about the visible film grain and lively Technicolor palette, which really pops when appropriate, whether it be the rich red of a London bus or the bright glow of neon signs or shop displays. Even the late afternoon mist (or should that be smog?) is handsomely captured here. How much of this is also evident on the Blu-ray transfer I’m not currently in a position to say, but I’m convinced that the 4K resolution and Dolby Vision UHD plays a significant part. The colour is more a little muted once we move into the judge’s house (actually a studio set in Rome), which has a sometimes earthy hue common to film scenes set in artificially lit locations, but brighter colours still really register here. The image detail in the post-title sequence footage is also much crisper, being particularly sharp on facial close-ups (you can see individual hairs and skin pores), of which there are many here. Shadow detail is particularly good, but the black levels are still solidly rendered, and any trace of dust or wear has been eradicated. A knockout restoration and transfer – the flat, sub-par screen grabs here (you can blame my software for that) don't come close to doing it justice.

You can choose to watch the film with either the original English or an Italian dub, both of which are presented here in 24-bit DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0 dual mono. Despite some inevitable tonal range restrictions (no thumping bass here), the English track is in very good shape, though there is a surprisingly wide dynamic range, with the result that if you crank up the volume to clearly hear the quieter whispers, you may well to have your eardrums blown asunder by a sudden piercing screech from Morricone’s score. The normal volume dialogue and that music is always clearly reproduced, however, and there is no trace of wear or background hiss.

The Italian track was produced for the domestic market, and while some of the voices are better matched to the characters than their English language equivalents, there are many times when the mismatch of dialogue to what the actors are saying is patently obvious, though this is far from unusual for dubbed Italian genre works. The condition of this track is not on a par with the English one, having a narrower tonal range that adds a fluffiness to dialogue and assures that the more screeching elements of the score become genuinely shrill. There’s also an audible background hiss in many scenes, and due to the condition of some parts of the track, it does briefly switch to its English language equivalent. When there is music only on the soundtrack – such as the title sequence and fun-in-town montage – the higher quality music from the English track appears to have been used.

Optional English subtitles for the Italian track have been included, as have optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired for the English language track.

Audio Commentary with David Flint and Adrian J Smith

Adrian Smith of the Movies and Mania website and David Flint from The Reprobate discuss a film that they believe is underrated in part because it’s not the giallo thriller that it’s often sold as and that many who view it are thus expecting. They provide details on the actors and director Enzo G. Castellari, discuss the character roles in the home invasion thriller and why these movies particularly resonate, and praise the cinematography and how the lighting ensures that the action is always clear even in the dark. Despite their fondness for the film, they do not shy away from criticising its logic holes, the dubbing issues, and the occasional odd directorial decisions. There’s also some discussion of the class-conflict and homoerotic subtexts, and they clearly have about as much respect for the character of the judge as I did. A useful and enjoyable companion to the film.

Enzo G Castellari: Directing Fear (24:16)

Director Enzo G. Castellari, interviewed in Italian with optional English subtitles, looks back at his entry into filmmaking and the only film on which he got to work alongside his prolific director father, Marino Girolami. Once he gets on to Cold Eyes of Fear, he takes us through the process of reshaping the initial script with Tito Carpi, his intention to make an intricately plotted low-budget film in a single environment, and reflects on the pleasure of working with the best people and many of his friends. He outlines some of the film’s distribution issues, and goes into some detail about the emotional problems suffered by leading man Frank Wolff, which fed into his character but later led to his tragic suicide. He also talks about hiring Ennio Morricone to compose the score, only to have him decide on an improvisational approach that I get the feeling Castellari was less than overjoyed with. “The result,” he says with a knowing grin, “is something I don’t need to talk about.” We even – thanks to some handy added dictionary captions – learn the difference between the Italian expressions mecojoni and sticazzi, and how they are used to judge the effectiveness of film titles.

Gianni Garko: An Italian in London (29:24)

Actor Gianni Garko, who plays Peter in the film, outlines how he selects roles and how his hesitance at doing another period piece led indirectly to him landing Cold Eyes of Fear. He talks briefly about his working relationship with his fellow actors, about director Enzo Castellari and the differing directorial styles of filmmakers he has worked with, how Italian cinema prefers its protagonists to look like real people rather than Hollywood stars, shooting on the streets of London with a hidden camera, and a good deal more. Looking back, he regrets that many of the characters he has played in films do not speak with his voice, and outlines how pressure from the Italian actors’ union, Sindacato Attori Italiano, helped to bring about a law that allowed actors to decide whether or not to dub their own voices.

Gianfranco Amicucci: The Men in the Editing Room (26:52)

Gianfranco Amicucci, the assistant editor on Cold Eyes of Fear, reveals that he only ended up involved in editing films because his dream of becoming a pilot was squashed, first by the expense of a pilot’s licence and then by his mother’s fear that he was going to get himself killed. He is brutally honest about editor Vincenzo Tomassi, whose assistant he was for several years, describing him as a nice person but “a typical crawler,” who was nicknamed ‘the worm’ by his colleagues because he never looked you in the face and cared only about money. It doesn’t end there, with Amicucci praising Tomassi’s editing in one breath and criticising it for being repetitive in the next. He reveals that when he first met Castellari, the man was so muscular he thought he was an acrobat, but the two soon found they had much in common and became good friends, and worked together many times in the years that followed. There are a few details about the making of Cold Eyes of Fear, but there’s considerably more on Castellari and his film work, and I have a feeling that fellow reviewer Camus – himself a film editor of many years standing – would nod in agreement when Amicucci complains about how deadlines have steadily shortened over the years, adding that editing is not about the increasingly fast cutting being demanded these days, but something that should have meaning within the film in question.

A Fearsome Collaboration: Lovely Jon on Morricone (15:07)

DJ and soundtrack enthusiast Lovely Jon provides a hugely useful introduction to the avant-garde free improvisation music group, Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza, whose members provided the score for Cold Eyes of Fear under direction of one of their number, a certain Ennio Morricone. He explores the origins of the group and the various influences on it before moving on to discuss its work on the film, then deconstructs in some detail the score for the giallo-esque post-title sequence. Not being a musician, I found this fascinating.

Desperate Moments Theatrical Trailer (3:17)

There are spoilers aplenty in this seriously trippy trailer set to one of the wilder tracks from the score. I would imagine it left audiences of the day wondering what the hell they were in for. I really liked it.

Image Gallery

16 screen of posters and what look like lobby cards, all scanned at pristine quality.

Also included with the retail release is an 80-page Book with a new essay by Roberto Curti, a new interview with Giovanna Ralli, an archival interview with actor Gianni Garko, archival news reports on the death of actor Frank Wolff, a career-spanning archival interview with director Enzo G Castellari conducted by Mark Wickum, an overview of contemporary critical responses, and full film credits, but this was not available for review. I’m sure it’s superb – they always are.

A film that steadily grew on me as I watched it for the first time and that drew me back for second and third viewings that highlighted its strengths and made its weaknesses seem less relevant. I even got used to the posh voice that poor old Fernando Rey was stuck with, and it certainly works for the film’s subtextual critique of those in positions of wealth and power. I came to this disc really late due to an act of spectacular stupidity on my part (one for a later blog, perhaps), but am so glad that I got around to it in the end. A top-notch restoration transfer and some excellent special feature make this an easy one to heartily recommend. Indicator just keeps knocking it out of the park.

|