| |

'We were inspired by legends from our area which speak to the species extinction that’s happening today. I think these stories act as vessels for wisdom and truth from times past. We can constantly mine them for knowledge we may be in danger of losing in the modern world.' |

| |

Tomm Moore |

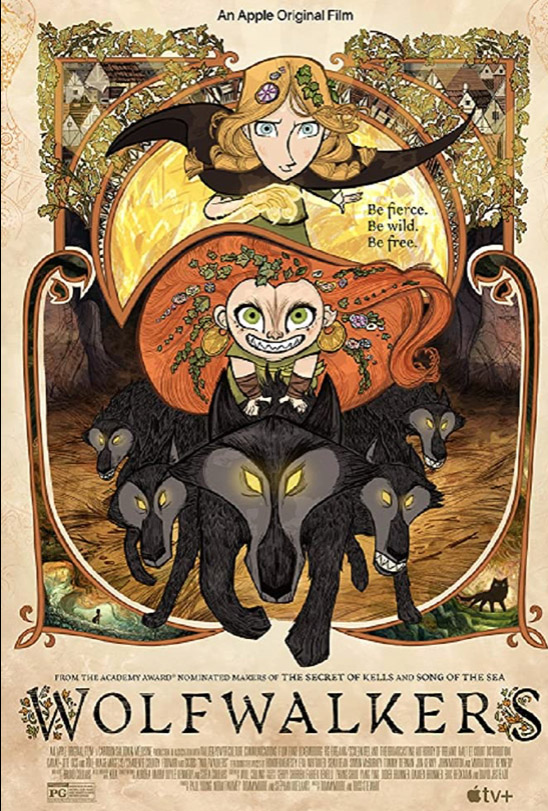

A new film from Cartoon Saloon, the internationally renowned animation studio based in the Irish city of Kilkenny, is a rare event worthy of celebration. Dozens of the world’s finest animators work tirelessly on each of the studio’s feature-length films, but the creation of cinematic magic requires a painstaking, unhurried approach which calls for patience on the part of their growing legion of admirers too. Wolfwalkers, which concludes the studio’s Irish folklore trilogy following the earlier success of The Secret of Kells (2010) and Song of the Sea (2015), is another dazzling wonder of the art of animation and well worth the wait. Although the film was digitally enhanced using TVPaint drawing software, and although it is a co-production with Apple, co-directors Tomm Moore and Ross Stewart are independent artists both and the film is indelibly stamped with their, and the studio’s inimitable style. Cartoon Saloon’s hauntingly beautiful illustrations, artisanal hand-drawn aesthetic, respect for ancient storytelling traditions, and sensitivity to the complexity of parent-child relations again coalesce in this exquisite and enthralling final instalment.

Cartoon Saloon’s last feature, The Breadwinner (2017), was adapted from Deborah Ellis’s award-winning trilogy of children’s novels and constituted a brave departure for the studio. It was their first adaptation but also broke new narrative ground by focusing on the story of an Afghan family living under Taliban rule. Like its predecessors, the film was critically acclaimed and Oscar-nominated. Wolfwalkers takes us back to Ireland, to the time of Cromwell’s subjugation of the Irish, and to Kilkenny. Having captured the walled garrison in 1650, the Lord Protector is determined to consolidate control, ‘tame’ the surrounding countryside and the Irish, and impose his new world order on those he sees as a Pagan affront to Christian values. He orders the eradication of the last pack of wolves in the woods beyond the city walls - as a prerequisite for deforestation, to deny cover to insurgent Irish rebels and English Royalists, and to provide timber for the Royal Navy.

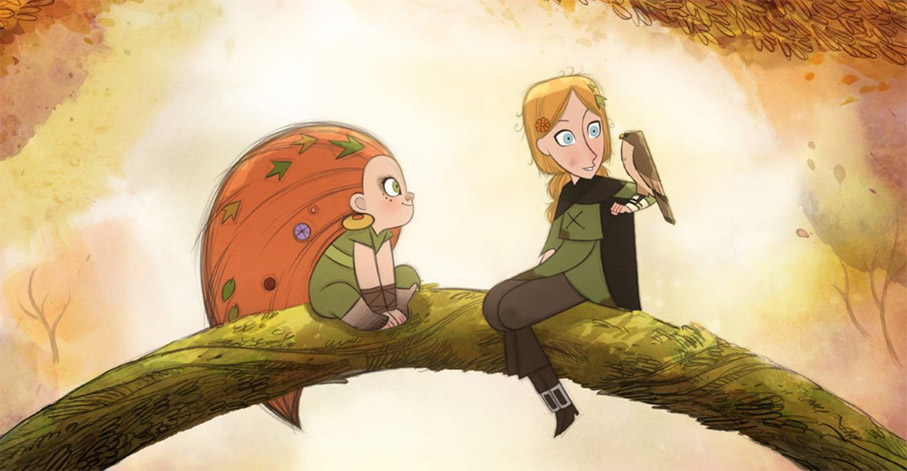

Cromwell assigns the detail to Trooper Bill Goodfellowe – an experienced hunter in his ranks whose work is complicated by his daughter Robyn’s restless high spirits. Goodfellowe has promised his late wife he’ll protect the girl and orders her to stay indoors, confining her to domestic servitude in house and scullery. Robyn is torn between loyalty and obedience to her father on the one hand, her insatiable curiosity and appetite for adventure on the other. In defiance of her stern father’s orders, she ventures into the woods, with her crossbow to hand and her pet hawk, Merlin, on her arm. Along the way, Robin careers into Meabh Óg MacTire - a wildly mischievous local lass with a scruffy shock of red hair who is also a shape-shifting wolfwalker of ancient legend – half-human-half-wolf and is able to transform herself into lupine form. After the two become fast friends, Robyn agrees to help Meabh find her long-lost mother, Moll, and after her new-found pal bites her during a play-fight, she is increasingly drawn into their world and into conflict with her father. She soon realizes that the imperilled wolves her father seeks to slay are benign and unjustly persecuted. Moll, it transpires, has been captured and caged by Cromwell and, as the plot thickens, Roybn must not only honour her promise to Meabh but persuade her father he’s doing great wrong and should switch sides.

© Cartoon Saloon – image reproduced with the kind permission of Tomm Moore

Wolfwalkers is a spellbinding, expertly executed masterwork that emanates from Kilkenny and feels entirely Irish but owes everything to international co-operation. Scriptwriter Will Collins was ably abetted by story consultant Jericca Cleland - a director and co-founder of Danish animation studio Nørlum. As he did on The Secret of Kells and Song of the Sea, French composer Bruno Coulais combines brilliantly with Irish folk band Kila to produce another stirring string-laden score that is by turns plaintive and thunderous. Two accomplished English thespians, Sean Bean (Goodyear) and Théâtre de Complicité director Simon McBurney (Cromwell), head the voice cast and earth the film’s entirely convincing aural landscape. Child actors Honor Kneafsey (Robyn) and Eva Whittaker (Meabh), though, match them line for line, and the Irish supporting cast, which includes Cartoon Saloon co-founders Nora Twomey (Head Housekeeper) and Paul Young (Woodcutter), are equally superb. A special mention must be made of Niamh Moyle’s amusing cameo as an inebriated fishmonger; it’s the kind of piquant detail characteristic of Cartoon Saloon’s work and lends credibility to the whole.

As in the earlier films in the folklore trilogy, the focus is on the growing pains of a free-spirited motherless child. Robyn’s stuttering friendship with Meabh develops and deepens through the trials they face together and acts as a compacted metaphor on the passage from the innocence of childhood into enlightened early adulthood. Tomm Moore and Ross Stewart respect the intelligence of audiences young and old, so they aren’t afraid to allude to the darker aspects of the human condition. They don’t shy from stockades and gallows. Kilkenny kids round on Robyn, an outsider in a foreign land, to bully and torment her. The citizenry and soldiery alike are shown to be in thrall to unfounded fears and deep-seated superstition. One suspect Moore and Stewart would agree with Thomas Mann, when he says, in Dr. Faustus, ‘This old, folkish layer survives in us all, and to speak as I really think, I do not consider religion the most adequate means of keeping it under lock and key. For that, literature alone avails, humanistic science, the ideal of the free and beautiful human being’. For them cinema, Celtic mythology, and the children charged with restoring the world’s despoiled beauty will prevail.

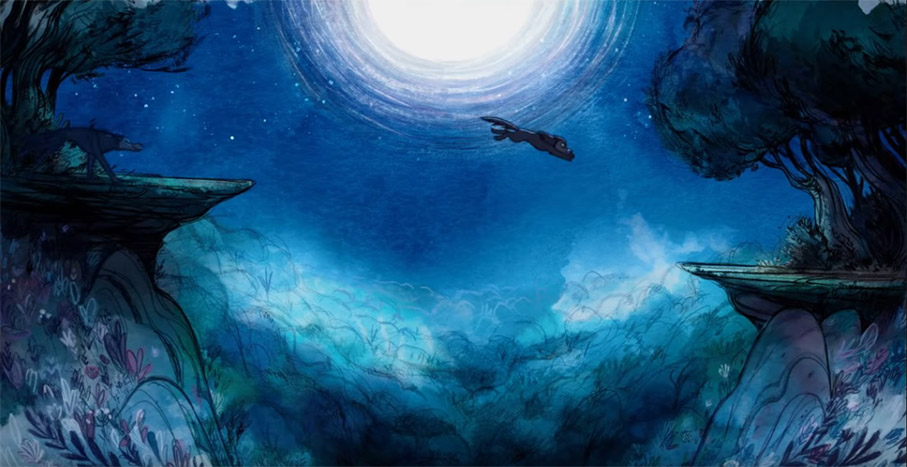

Their beguilingly simple fable, then, is also a tale of subtle and profound complexity. Wolfwalkers is full of conflict and contrast: between authority and obedience, city and country, English (Puritan) iconoclasm and Irish (Pagan) idolatry, proto-modernity and ancient pre-Celtic lore, and, ultimately, between the ‘civilised’, ‘civilising’ credo of the colonists and a resistant, more organic indigenous mythology. These contrasts are brilliantly delineated in stark visual counterpoint. Cartoon Saloon drew on the muted colour palette of woodblock Puritan pamphlets for their flatly geometric representations of the city. By contrast, they, again, deploy the loose spiralling shapes of Pictish art to paint the otherworldly forest in lustrous weeping watercolours. For the city they use grey-brown, slate grey, and midnight black: for the country - nocturnal blue, autumnal amber, and assorted spring greens.

Wolfwalkers is a tale of goodies and the baddies rendered in colour and form and its visual contradistinctions underpin an understated environmental sensibility. Tomm Moore is currently working on a short film for Greenpeace and is outspoken about the parallels between Bolsonaro’s destruction of the Amazonian rainforests and Cromwell’s policy of deforestation. In both Brazil and Ireland, indigenous people were driven from their land by avaricious, accumulative forces intent on the pillage of precious resources. Despite Cartoon Saloon’s commitment to craft skills and a hand-drawn, painterly aesthetic, it might be more useful, therefore, to compare Wolfwalkers to James Cameron’s CGI-heavy mock-environmental blockbuster Avatar than any film from Studio Ghibli – a formative influence though the Japanese studio certainly was for Cartoon Saloon and important though films like My Neighbour Totoro and The Tale of the Princess Kaguya were for them.

Comparisons with Avatar might seem far-fetched but Robyn and Meabh, after all, escape the restraints of authority by assuming alternative physical form and rapacious imperial power is contested in both films. The forest beyond Kilkenny might double for the Tree of Souls, the fair-skinned Irish for the blue-skinned Na’vis, and Cromwell for Colonel Quaritch. Finally, the wolves rush to the rescue in Wolfwalkers just as Pandoran wildlife does in Avatar. The analogy may break down over differences of budget, sustainability, and style but similarities between the films seem obvious, notably both films privilege ancient, heretic pantheistic traditions over the more recent Christian belief systems of our moment.

As they did in Song of the Sea, Moore and Stewart again delved deep into pre-Celtic and Celtic mythology for inspiration. It is that emphasis on local lore, and their implicit insistence on the importance of place and identity, that make Wolfwalkers so special. For his debut feature Silence, the Irish filmmaker Collins travelled across Ireland interviewing people for his meditation on the elusiveness of tranquillity, the longevity and durability of Irish legends, and the palimpsestic nature of Irish myth and memory. One of those he ‘encounters’ says, ‘The mind turns upon silence. Such an old, humanised country we have, you know. Two-way transmission between people and places. Legends heaped upon legends, lore heaped on lore, names heaped on names’. Moore and Steward peel back layer upon layer of Celtic myth. In particular, they tap into legends of the wolf-folk of the Kingdom of Ossary, in which humans were able to transform themselves into wolves at will. The Book of the Dunn Cow, which may have been written as early as the 11th century and is the oldest surviving manuscript in Irish Gaelic, contains many references to such transformations. The wolfwalkers of Cartoon Saloon’s film are direct descendants of far earlier Pagan, possibly pre-Christian mythic figures.

Tales of wolf-men and werewolves were certainly prevalent in Ireland long before Feudalism and the Dark Ages. More recently, they were intimately bound up with legends of the fianna - guerrilla bands of landless Irishmen who came together in hunting and raiding parties, wolf-warriors who were called luchthonn (wolf skin). Like the Scotch Cattle of Wales, they symbolised resistance to authority and probably took their name from a favoured form of disguise. All of which makes the connection between the wolfwalkers of the film and the history of Irish rebellion clearer and makes the characterisations in it more potent. In Wolfwalkers, Robyn essentially becomes an honorary Irishwoman while her friend Meabh becomes an honorary Irish rebel. Irish rebels, given corporeal form as wolfwalkers, are presented as freer and purer, more natural and noble than those who hunt them.

All of which makes the film’s representations of Robyn and her father more interesting too. Both speak in northern English accents, in contrast to the brutal English soldiers who have cockney accents. What does this signify? To ask that question is to wonder what, and where the north is, which nobody can categorically say. Draw a line between the Mersey and the Humber and you come close to a useful working definition of the English North but there’s another, Upper North - harder still to define, encompassing the Lowlands of Scotland and stretching up to the Gàidhealtachd regions of the Highlands and Islands. So, presenting Robyn and her father as northerners implies both a sense of pan-Celtic solidarity and respect for those Northern English characteristics born of hard graft, hard times and hard weather: defiance of cupidity and frippery, fixity of purpose and principle, grit, guts, stubbornness, tenacity, taciturnity – qualities Robyn and her father possess in abundance.

At this point, praise of Wolfwalkers must be tempered with a slight reservation. In a film of such depth and symbolic subtleties, many will be disappointed with the film’s reductive and revisionist portrayal of Cromwell. The Lord Protector’s religious zealotry may be represented accurately enough but by painting him as comic-book villain, as the film does, distorts the wider historical picture. Never mind that Cromwell established Britain’s only Republic, the Mother of All Parliaments, and the principles on which modern democracies are based, what about his actions in Kilkenny and Ireland? Cromwell invaded Ireland (over the objections of mutinous Levellers) not primarily to subjugate the Catholic Irish but, specifically, to defeat the regrouped English Royalists and their allies within the Irish Confederacy. Many Royalists fled to Ireland after their defeat by the New Model Army and many joined forces with the Duke of Ormond’s Royalist-Confederate coalition. Later Earl of Ossary, Ormond was the owner of Kilkenny Castle and the tyrant Charles 1’s representative in Ireland. He can have had few complaints that Cromwell seized the castle and the city, and grateful they weren’t sacked.

The infamous massacre of Drogheda prior to the siege of Kilkenny is another matter. Often cited to indict Cromwell of barbarism, it was primarily directed at those guilty English Royalists whom Cromwell described as ‘barbarous wretches who have imbrued their hands in so much innocent blood’. And even as barbarous and sanguinary a figure as General Sir Frank Kitson acknowledges that such horrors were common in the warfare of that period. In Old Ironsides, his military biography of Cromwell, Kitson says, ‘His determination to slaughter the garrison after Ashton had refused his summons to surrender was consistent with the contemporary rules of war as practised on the continent’. This is not the place for a defence of Cromwell, and I wouldn’t be the man for the job anyway, but it is a blemish on the film and if filmmakers opt to consider history it’s fitting we should consider it too.

There are few more amusing paradoxes in modern cinema than the sight of the Lord Protector being played in Ken Hughes’ Cromwell by Richard Harris - a proud Irishman averse to religious dogma and famously fond of a licentious knees-up. A similar paradox is present in Wolfwalkers, for the film’s superficial portrayal of Cromwell is completely at odds with the its overarching themes of friendship across divides, mutual respect and understanding. Stendhal once said that introducing politics into the novel was like firing a pistol shot in a concert. Yet his novel The Charterhouse of Parma was a dissection of Restoration Europe after 1815 and his masterpiece The Scarlet and the Black was a celebration and lament for Napoleon. Politics is embedded in culture whether we like it or not, and to object that arguments such as those posited above have no place in discussion of ‘a children’s film’ is to do a disservice to the complexity of Wolfwalkers – in more ways than one.

As Blair Worden says in Roundhead Reputations, ‘We may be tempted by what we have seen of the treatment, by successive generations, of Puritans and Republicans, of Cromwell and the Levellers, to despair at the mutability of historical understanding . . . So we should, were it not for the past’s capacity to answer back: to yield discoveries to which, at least within a pluralist polity, our preconceptions have to adjust . . . an entry into values peculiar to another time will teach us how ephemeral may be those dominant in our own’. Again, it is ironic that Moore and Stewart refreshingly remind us of the values of other times and demonstrate the transience of our own while distorting the historical record they reflect so accurately elsewhere. That blemish aside, it’s hard to find fault with Wolfwalkers.

There is mystery and magic enough in it to delight adults as well as tots. Moore and Stewart may unfairly misrepresent Cromwell as surely as Ken Hughes’s hagiography did, but we can forgive them; they’re Irish and be dead fish if they didn’t feel deep anger at the damage done by Cromwell on their island. Their research into history may fall short but their knowledge of Celtic myth is prodigious. Legends about wolf-folk was a pan-European as well as pan-Celtic phenomenon, as the German myth of the werewolf testifies. European Myths of werewolves are darker by far than those in the local Celtic tradition and Cartoon Saloon’s wolfwalkers reflect a more congenial kind of mythic figure.

The wolves in The Secret of Kells were of the threatening, lethal variety whereas those in Wolfwalkers are benign, often depicted as gambolling puppies rather than the marauding predatory ‘beasts’ Cromwell vows to destroy. Robyn Goodfellowe might be a figure from Little Red Riding Hood, the naïve young girl foolishly ignoring parental advice and warnings, but we never feel that Moore and Stewart’s wolves will eat her as the Big Bad Wolf ate Little Red Riding Hood and her grandmother. As Bruno Bettelheim notes in The Uses of Enchantment, the age-old story of Little Red Riding Hood changed with Perault’s later versions, in which a woodcutter rescues the girl; and, with the Brothers’ Grimm version, Little Red Cap, in which the wolf is drowned.

Bettelheim himself analysed the story using the concepts of Freudian psychology and with the Big Bad Wolf as a sexual predator. Nothing could be further from Moore or Stewart’ mind: it is environmental, moral, and political metaphors not sexual ones they weave. The late, great Chris Marker used wolves to environmental and political ends too. He concludes his magisterial 1977 film on political struggle, A Grin Without a Cat, with footage of a modern wolf hunt - in which the wild creatures are culled with telescopic rifles from helicopters. The wolves, here, represent those free spirits who fought for liberty, equality, and human solidarity - but failed to achieve their ends. The film’s final line: ’A comforting thought . . . some wolves still survive’.

It’s a comforting thought that Cartoon Saloon have survived for over 20 years and will be back with more films, perhaps one in which wolves return from remote hiding places to teach human beings respect for the environment and each other. Once again, we may have to wait a while and hope our patience will be rewarded with something as ethereally beautiful and entrancing, as enchanting and thought-provoking, as richly textured and deeply layered as Wolfwalker. Ross Stewart’s earlier work with Cartoon Saloon includes a short film, Cúl an Tí/The Back of the House, which featured in a TG4 series celebrating the tradition of sean-nós singing still surviving in the Gaeltacht regions of Ireland. The film cites a popular poem by the great Irish poet Seán Ó Riordáin. A lifelong TB sufferer Ó Riordáin once wrote: ‘I die again with every word/But rise again with every breath’. Each successive film from Cartoon Saloon is a kind of death and resurrection. We wish them long life, and many of them.

Vladimir Vysotsky’s Wolf Hunt: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ROmlFJamIuY

|