|

When Tomm Moore, Nora Twomey and Paul Young founded the Cartoon Saloon in 1998, their bold decision to gamble on their own talents and push out on their own must have felt foolhardy. Although the Celtic Tiger had sprung into short-lived life, Sullivan Bluth Studios (the animation powerhouse that helped establish the course on which all three learned their craft) had gone under in 1995, and the Irish animation industry was all at sea. The trend toward cold, corporate CGI methods made the trio's commitment to independence and the hand-drawn aesthetic of traditional animation appear doubly quixotic.

Many feared the Kilkenny atelier would share the fate of its esteemed predecessor. Instead, Moore & co steadied the ship with a series of captivating shorts, such as Nora Twomey's From Darkness (2002), and a wonderful TV series, Skunk Fu! (2007-8). They then consolidated their growing reputation with The Secret of Kells (2009), a gorgeous first feature that secured an Academy Award animation nomination and revived Irish animation, practically overnight and single-handedly.

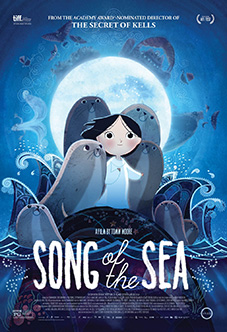

It is fitting that their latest feature, Song of the Sea, earned the Cartoon Saloon a second Oscar nod alongside Studio Ghibli's The Tale of Princess Kaguya and Disneys' Big Hero 6, the ultimate winner. Tomm Moore's exquisite 2D gem is worth worth half a dozen loudly heralded CGI 'toons', and, although the influence of Isao Takahata and Studio Gibhli is evident in the film's soulful tints and tone, its originality places the Irish artists in the front rank of world animation where their Japanese counterparts once proudly stood. A European co-production showcasing studios in Belgium, Denmark, France, and Luxembourg as well as Ireland, Song of the Sea is earthed in the fertile soil of Celtic myth but soars above the local.

There is much about this enchanting, cumulatively moving film that defies expectation, not least its refreshing refusal of the patronisingly simplistic binary of good and evil. Though nominally set in the eighties, it is timeless; though brightly genial it unfolds beneath sombre skies. A quote from W.B. Yeats's poem The Stolen Child establishes a bittersweet atmosphere of magic and melancholia from the outset: “To and fro we leap /And chase the frothy bubbles/While the world is full of troubles/ And anxious in its sleep/ Come away/O human child! /To the waters and the wild /With a faery, hand in hand/For the world's more full of weeping than you can understand.”

Song of the Sea superimposes a beguiling, completely convincing coming-of-age story upon a delicately woven tapestry of Gaelic folklore. It is a tale of tales to melt the hardest of hearts. The film's sparky hero, Ben, lives in a lonely lighthouse with his mute younger sister, Saoirse (Freedom), his taciturn father, Connor, and his irrepressible best friend, Old English sheepdog Cú (Hound). His sensitively delineated growing pains are compounded by sibling rivalry and family grief. A gentle giant, Connor is benumbed by pain at loss of his beloved wife, Bronach (Sorrowful), who was claimed by the sea on the fateful night Saoirse (the last selkie or seal-child of legend) entered the world. Ben's primordial fear of water is only barely restrained by his orange lifejacket, but his sister is inexorably drawn to the deep. Saoirse's moonlight dip with a group of seals provides the kids' stiff-necked oul granny with just the excuse she needs to whisk them off to the supposed safety of her house in Dublin. Pining for their father, Ben and Soairse immediately run away, guided homeward by the feathery motes Saoirse calls forth from the conch shell bequeathed by their mother along with the equally magical coat with which Saoirse must be reunited on pain of death.

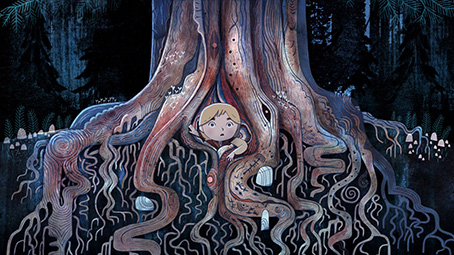

The kids' incredible journey takes them through Dublin traffic and lush countryside, holy wells and underground lagoons, fairy forts and stone circles marked with Pictish Ogham carvings. Their adventures pit them against the owl witch, Macha, who steals feelings, turns fairies to stone, and is as emotionally frozen as her son, the mythical granite giant Manannán mac Lir. The interconnected stories of Granny and Macha, Connor and Mac Lir are tied together by the expertly modulated voices of Brendan Gleeson and Fionnula Flanagan respectively. While David Rawle inevitably steals the show as Ben, the voice cast are flawless throughout. Special mention, though, must be made of Liam Hourican's sidesplitting turns both as a lackadaisical Dublin bus driver and as Spud, leader of three musical fairies Ben and Saoirse encounter.

The stories of human and mythic creatures alike warn us of the price we pay for bottling up emotion and allowing our hearts to turn to stone. A palpable sense of spirit worlds alive in the present is wonderfully evoked by the ethereal compositions of Bruno Coulais, the lilting fiddles and flutes of folk group Kíla, and the haunting song of Lisa Hannigan (whose debut LP was presciently titled Sea Saw). The film's understated soundtrack complements the delicate watercolours and muted palette art director Adrien Merigeau deploys to bring landscapes, skyscapes and seascapes to life before our delighted eyes. The film's component parts harmoniously merge to make the film dance a jig on screen are testimony to the patience and painstaking attention to detail of all involved in the film's lengthy, labour-intensive production.

Song of the Sea is a treasure trove of myth and magic, fable and fairytale. The dynamic but subtle ways Tomm Moore and Will Collins spin their yarns drive the film forward with an irresistible rhythm echoed in the Bodhrán's rolling bass. The complex narrative patterns they weave belie their familiarity with seanchaí lore and suggest they immersed themselves in time-honoured classics such as the mediaeval Yellow Book of Lecan, Yates's The Celtic Twilight, David Thomson's The People of the Sea and Duncan Williamson's Land of the Seal People. The myths Moore and Collins assemble from such sources nestle naturally alongside their own childhood memories to produce a coherent and poignant blend of the ancient and modern. It would be puerile to label this a 'children's film'; anybody who has experienced sibling rivalry or the loss of a loved one will be stirred by it, though I hope nobody will be profoundly moved by the film for the reasons I was.

I first saw Song of the Sea at the tail end of the 2014 London Film Festival, within days of laying my mother to rest in a woodland burial site in Cumbria. She had been diagnosed with terminal cancer just before the festival began and died, with extraordinary dignity and fortitude, within a fortnight of complaining of stomach pains, having refused chemotherapy. That catastrophic, testing time was, naturally, one of intense emotions for me. Though we know death is our common destiny (as Larkin said, “most things will never happen: this one will”) sudden loss still shocks. No shock I'd ever experienced, though, hit me with the unanchoring force of the one I felt when my Mum died. Like Connor in Moore's film, I was benumbed with grief; like Connor, I'd turned in on myself and buried my anguish deep within for the sake of my sister, my father, and others. Little wonder then that, though I cry readily in cinemas, I've never wept with such overwhelming pain, relief and, perverse though this will sound, joy as I did as I watched Song of the Sea. Images burn themselves on memory the more indelibly the more intense our feelings and there are scenes in it I hope I never forget. Certainly, I have never, before or since, been as moved by any other film as I was by Moore's magical delight.

As if there weren't material enough in the film's story arc alone to elicit profound reaction, my pain was drawn out by additional extra-cinematic coincidences and resonances. At the precise moment I heard the news of my mother's fatal cancer, I was clattering back to Lancaster from Millom by train. On Mum's insistence, I'd undertaken a pre-planned pilgrimage to the home of the great Cumbrian poet Norman Nicholson, who grew up in Millom when it was a thriving iron town and remained there 'til his death. The skyline above the town, once punctured by blast furnaces and bellowing chimneys, is dominated by Black Combe. That gigantic prominence bears a distinct resemblance to Benbulben, the mountain in Co. Sligo that overlooks the lighthouse in The Song of the Sea (2014 was a big year for Benbulben: it also featured in John Michael McDonagh's magnificent film Calvary). Seeing Benbulben in Moore's film, I was reminded of Black Combe, Millom, my mother, and my pain. I was off again, oblivious to who might detect my tears.

I now remember a line from Nicholson's poem Cloud on Black Combe: “The air clarifies/Rain/Has clocked off for the day/The wind scolds in from Sligo/Ripping the calico-grey from a pale sky/ Black Combe holds tight/To its tuft of cloud, but over the three-legged island/All the West is shining.” Looking out from Black Combe across the Irish Sea, beyond the Isle of Man (formed, legend has it, during a fight between the giants Finn MacCoul and Banandonnner), the Emerald Isle is visible on a clear day. As I watched The Song of the Sea, I pictured Ireland from Black Combe and didn't need Yeats to remind me that the world is full of troubles and weeping. This joyful, sorrowful, funny and inexpressibly beautiful film made me cry when I most needed to do so; now it makes me smile inside as well.

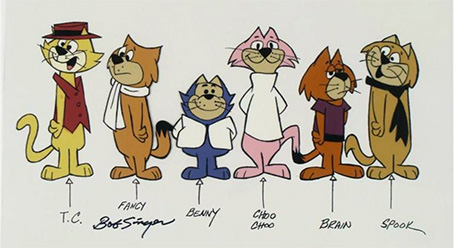

It sits among my favourite things alongside the poems of Norman Nicholson and Freddi Chaplain's Rupert the Bear albums – on a special shelf for cartoons with Halas and Bachelor's Animal Farm (1954), Hanna-Barbera's Top Cat (1961-62), Disney's 101 Dalmations (1961), Roman Kachanov's Mitten (1967), Fedor Khitruk's Vinni-Puh (1969), Sylvain Chomet's The Illusionist (2010), and Takahata's The Tale of Princess Kaguya. The season of goodwill and gifts is almost upon us; go on, make somebody you love happy, buy them Song of the Sea.

A wonderfully crisp 1.85:1 transfer that delivers pin-sharp line art edges without any visible enhancement, giving the image a lovely, clean look that really showcases the artwork. The colours are very attractively reproduced and are never over-saturated and there are no motion glitches or obvious compression artefacts.

There are two soundtrack options available, English DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 surround and Gaelic DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 surround. As you would expect from a modern sound mix, the results are clean, clear and boast a strong dynamic range, something particularly evident in the music score and some of the louder sound effects. There is some frontal separation, though the dialogue tends to sit front and centre. Only the music score really makes use of the surrounds, and that is still front weighted. The music on the English language track is very slightly louder and richer than on the Gaelic track, a difference that is more pronounced during the closing credits.

Optional English subtitles are available for either soundtrack, but it’s worth noting that they are SDH subs and thus also describe sound effects as well as reproducing or translating the dialogue.

Audio Commentary with Tomm Moore

Tomm Moore talks us through the making of the film from conception to completion and the way they edited down 'the fat baby' of the original script to more conventional proportions. Moore's style is charmingly convivial and chatty. His enthusiasm is infectious. It is clear he loved everything about this project and that he respects his many collaborators. He reveals many of the fascinating minor details that add to the film's local authenticity. For instance, he tells us that the three figures painted into the background of a passing 'shot' of the statue of Molly Malone in Dublin are his good self, and animators Elliot Cowen and Todd Paulsen.

It's a shame the cheeky 'Feck off' he takes great in delight in was removed from the film before it reached us, but at least he gets in a nod to his hurling team (Kilkenny GAA, 'the Cats'), gets his name on a pub (the 'Ó Mórdha'), and got to keep the lovely common and garden exclamations 'Janey Mackerel', 'Holy Moly' and 'Jesus, Mary, and Joseph'. Moore talks eloquently about the Cartoon Saloon's sensibility and their hand-drawn aesthetic. Unsurprisingly, he cites Yugo Serikawa's The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon (1963), Hayao Miyazaki's My Neighbour Totoro (1988) and Isao Takahata's The Tale of Princess Kaguya (2013) among the films that influenced his style.

The one point on which this reviewer would take issue with Moore relates to his recollection of the time he and his son stumbled across dead seals lined up on a beach at Dingle. Moore accepts at face value the view of a local woman who blames this cruel slaughter on the local fishermen's frustration at depleted fish stocks. He seems to share her view that 'we' are less connected now to the natural environment than was the case when more widespread familiarity with ancient mythys persuaded people to respect other creatures more. Would that that were so. I suspect seals have been slaughtered down the ages, enriching mythology or no. In the lyrical opening chapter of his 1936 autobiography, On Another Man's Wound, Ernie O Malley, recalls his boyhood adventure off the West Coast: “We sailed on the stout-nosed fishing smacks of Clew Bay, where there are few traditions. Farther out, beyond the Bar, was rough sea, and the story-tellers of Achill and Clare Island. Near the steep, swarthy cliffs of Achill men shot the seals that gluttoned on fish.”

Behind the Scenes (2:49)

Here Tomm Moore offers us wonderful glimpses of Cartoon Saloon artists at work and further insights into the way the film is put together by the various teams across Europe, no mean feat on a small budget just shy of five and half million euros. This can be played with or wiothout a commentary by Tomm Moore.

The Art of Song of the Sea (7:24)

This reviewer has watched this feature over and over. It is a privilege to see the original artwork. As Moore says in his commentary, there is far less difference between the concept art and the finished art than one might expect. Perhaps the bold ligne claire style is more prounounced and the characters more round-eyed, but otherwise less finesse is lost than is usual in the production process.

Also: A Trailer (0:56), a short Animation Tests (7:27) item and four quality Postcards bearing artwork from the film.

A rare gem to treasure. A beautiful tribute to the dying art of human-hand-drawn animation. The film's reputation can only grow as word of mouth extends its reach. Tomm Moore and the fine folk at Cartoon Saloon will be hard pressed to produce finer work but this one will do fine, just fine thank you very very much indeed, for the time being. Moore please! The Studio Canal Blu-ray of Song of the Sea will solve all your seasonal presents problems at a go. Highly Recommended.

Fedor Khitruk's Vinni-Puh: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=73uIn56G1YE

Roman Kachanov's Mitten: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6VqEGr8qM1M

|