"Terrorism is the war of the poor, war is the terrorism of the rich." |

Peter Ustinov |

"In the moment of crisis, the wise build bridges and the foolish build dams." |

Nigerian proverb |

It is nearly ten years since Mauritanian director Abderrahmane Sissako brought his inimitable style to bear on the depredations of global capitalism in his last feature film, Bamako. A masterpiece of poetic polemic, a trial film like no other, it combines a coruscating indictment of the IMF and World Bank with a delightful picture of everyday life in West Africa. In an enclosed courtyard in the titular capital of Mali, ordinary Africans speak out against the walls of indebtedness and poverty that circumscribe their lives. As the evidence mounts, those self-same lives unfold in the foreground and, astonishingly, a Western starring Danny Glover plays in the background. Many regarded it as the most beautiful and important film of 2006.

The wind of change has been blowing strong and steady since then. Those who claim to safeguard 'our' interests have rendered the world less equitable and more dangerous in the interim. Global inequality has increased exponentially. The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have exacerbated historic animosities, acted as recruitment drives for insurgent religious fundamentalism, and generated a cyclone of violence that may spiral for generations. If 'we' sowed that wind, 'they' are reaping its whirlwind. The international brigades of Islamic reaction, armed to the teeth with weapons forged in Western factories and captured from armies in flight, have seized vast stretches of Africa, Southeast Asia and the Middle East, forcing millions into exile and subjecting captive populations to systematic repression. What a world.

In his award-winning new film, Timbuktu, Sissako returns to Mali to peel the mask off 'Fascism with an Islamic face' and implicitly take stock of the 'new world order'. As he did in Bamako, he combines the local and the global, the personal and the political, without ever allowing his anger to overwhelm his humanity. Once again, he depicts an ancient way of life (here, that of the Bambara and Taureg peoples) while examining a modern form of tyranny. Again, he tackles pressing political questions with wit and warmth. Timbuktu is another timely and timeless masterpiece from a director now firmly established among the most gifted in world cinema.

Although based on the short-lived occupation of Timbuktu by Malian Jihadists in 2012, the film was actually shot in Mauritania and presents a composite portrait of continuing Islamic insurgency. Despite its dark subject matter, Timbuktu is a joy to behold, as critics have been at pains to point out. It looks and sounds sublime. The superlative work of Tunisian cinematographer Sofian El Fani and Franco-Tunisian composer Amine Boufine perfectly compliments Sissako's own keen eye and attuned ear. In less capable hands the film might have been weighed down by its freight of meaning, but Sissako has the knack of extracting beauty from the most ugly of circumstances. He takes politics seriously but treats it with the lightest of touches.

In Bamako, he earths the grand trial of globalisation in the tribulations of a bickering couple – a singer, Melé (Aïssa Maïga), and her unemployed husband, Chaka (Tiécoura Traoré). In Timbuktu, a Taureg family – Kidane (Ibrahim Ahmed), his wife Satima (Toulou Kiki), and their daughter Toya (Layla Walet Mohamed) – provide the human foundation on which he builds his fragmentary, overarching narrative about the horrors of autocratic fundamentalist rule.

The close-knit family live in splendid isolation beneath a tent pitched in rolling dunes beyond the city. Kidane is an intelligent, introspective cattle herder who refused to be uprooted when his neighbours fled the Jihadists. He is sanguine about the dramatic changes sweeping the region. All things pass, he thinks. Salima misses people and is frequently pestered by a lonely, slightly lascivious Jihadist, Abdelkrim (Abel Jafri), but she is protected by her stoic inner-strength. They are content.

Sadly, the family's peaceful existence is short-lived. When their favourite cow, 'GPS', loses his bearings and stumbles into the nets of a local fisherman, Amadou (Amadou Haidara), a tragic chain of events is unleashed. Amadou kills the cow and, in the subsequent confrontation, Kidane accidentally kills Amadou. The law takes its course and the film builds to a brilliantly choreographed, heartbreaking climax.

Certain films drop into our culture and our thoughts like stones disturbing still water, pushing out ideas and feeling in interlocking arcs, generating currents of association and memory. The splendour of Sissako's style isn't the only reason Bamako and Timbuktu have embedded themselves in my mind. It was while watching films at raucous open-air screenings in Africa that I fell in love with cinema, so Sissako's films hit me with particular force. I spent long stretches of my youth in Nigeria and Saudi Arabia, so they remind me of bony cattle and chirruping crickets, scorching heat and Harmattan sand storms, mud mosques and the muezzins' call-to-prayer, towering groundnut pyramids and limpid skies above the Sahara's endless edge. They also remind me of blood and swords: of the hacked corpse a Hausa magardi proudly showed me one night in Kano and the dull thud of a head hitting dusty ground at a beheading one afternoon in Dharan.

Earlier this week Saudi Arabia's record-breaking hundredth beheading of 2015 took place. Less than a third of those executed were found guilty under the Qisas (an eye for an eye) rulings of Sharia law. Nigeria has witnessed some of the worse atrocities perpetrated by those whose activities are partly funded by Saudi gold. Late last year, two hundred Muslims were killed during a Boko Haram attack on Kano mosque. Friday prayer had just begun when the suicide bombers struck. Just a couple of days ago, dozens died when Boko Haram bombs exploded in Monguno. Most, if not all of the schoolgirls kidnapped in Chibok last year are still in captivity. I often wonder how many of the lad and lasses I was at school with grew up to kill or be killed.

My adolescent experience of Africa and the Middle East didn't immediately improve my grasp of regional politics. Thought followed feeling, as it does in Abderrahmane Sissako's films. My background did, however, hugely increase my appreciation of his nuanced, non-judgemental approach. In Timbuktu, he de-demonizes Jihadists and demonstrates that Islam is as expansive, varied and riddled with crazy contradictions as Christianity. He reminds us that Islam is, as it were, a broad church.

In Challenge to Death, an anthology of writing on the problems of war and peace, Vera Brittain says: "In masculine minds there is often a confused identification of virility with the possession and use of weapons." The gun-wielding mujahideen we see in the film are the last word in fragile machismo. They cling to their weapons as if to comfort-blankets. Lesser directors have been happy to stereotype Jihadists as blood-crazed fanatics; Sissako, typically, suggests they are as various as they are numerous. They are sensitive and gentle as well as deluded and dangerous, hypocritical as well as sincere. Sissako tackles authoritarian absolutism with subtlety, contained anger and steely conviction, without descending to shallow didacticism.

In a film replete with stunning cinematography and unforgettable images, one of the most discussed scenes is that showing a group of local lads play football, without a ball. The 'beautiful game' may have been besmirched by its corrupt governing body but, in Timbuktu, the Islamic governing body has banned it outright. Sissako uses football, the Esparanto of the dispossessed, as another metaphor – for repression, freedom, and the irreversible penetration of modernity. While Jihadists debate the relative merits of Messi and Zidane, the locals respond to repression with ingenious resistance. Such is their love of the game it is enough to imagine the ball's trajectory. It is enough to pretend, and when a patrol of Jihadists appear on motorbikes they pretend they are taking 'healthy', officially sanctioned exercise.

This heart-warming, if minor defeat for the Islamic thought police belies a pervasive tyranny – the antecedents for which need no gloss when we can speak, without exaggeration, of troops enforcing insane edicts dispatched from a high command bent on world domination. Intimidating Jihadists patrol the streets around the clock, delivering chilling commandments to citizens controlled by force of arms: no football, no music, no smoking, no sex; socks and gloves are compulsory; men must wear their trousers legs rolled up. The threat of violence is ever present. One couple is publicly flogged, another couple are buried up to their necks in sand and stoned.

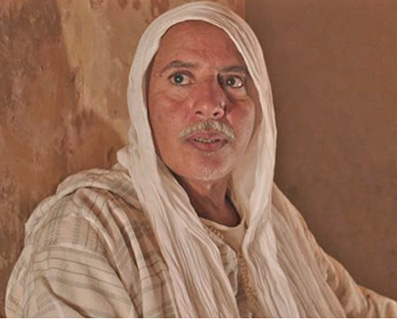

Among the many sympathetic characters we meet in the film is a decent, devout Imam (Adel Mahmoud Cherif, who bears a striking resemblance to Sissako). He patiently upbraids Jihadists for entering a mosque fully armed, at prayer time. "Here in Timbuktu," he says, "he who dedicates himself to religion uses his head not his weapons." Later, he intervenes on behalf of a woman whose daughter has been allocated to a Jihadist and attempts to prevent a forced marriage. He also defends an outspoken fishmonger who refuses to conform when ordered to wear gloves. "How," she asks, "can I sell fish wearing gloves?" The Imam speaks for her, for Sissako (who co-scripted Timbuktu with Kessen Tall), and, up to a point, for us when he asks: "Where is leniency? Where is forgiveness? Where is piety? Where is exchange? Exchange! Where is God in all of this?"

Admirable as the Imam and Kidane are, it is the women of Timbuktu who most often demand and deserve respect. It is they who most consistently and courageously resist. There is a distinct feminist undercurrent to the film. A fearless, presumably damaged 'witch', Zabou (Keetly Noel), faces down the Jihadists with careless abandon: she flings insults at them over her shoulder and, in the film's most direct act of resistance, stands with arms outstetched, like the lone student of Tiananmen Square, to block the progress of one of their jeeps. We fear for her safety as we fear for the fishmonger and, indeed, for all Muslim women trapped in a culture of endemic institutionalised misogny.

That last, reductive comment courts controversy and demands clarification. Misogny is not, of course, confined to African or Arab patriarchies. As Sissako ably shows, Muslim women are no more uniformly supine than Muslim societies are rigidly monolithic. And the wearing of a burqa, chador, hijab or yashmak is no more indicative of servility than the wearing of a Keffiyeh, Kuffi, Tagelmust or Turban. Intense heat dictates adequate headdress. It's worth noting, too, that pre-existent Arab misogyny was exacerbated by 'divide and conquer' European imperialism. The twisted sense of solidarity implied by the widely-used phrase 'My Arab brother before my Western sister', however, shouldn't blind us to the problems Muslim women face, problems all too evident in Timbuktu.

At the start of the film, we see carved African figurines being used for target practice. The bullets that rip the innocent statues tear, too, at human flesh and civilisation itself. This indelible image is typical of the effortless way Sissako moves between pointillist detail and symbolic grandeur. In this emblematic sequence Sissako immediately insinuates the idea of horrific violence while alluding explicitly to the desecration of mosques and destruction of cultural treasures by unhinged Jihadists. Although such iconoclastic zeal has a shameful history within Islam (and was, of course, common practise during periods of Puritan insurgency), this, Sissako seems to say, something new. The 'war on terror' certainly intensified the doomed struggle of the desperate poor against modernity and produced fresh forms of hypocrisy.

Here, Sissako sculpts additional symbolic meaning from that embedded in the film's title. For centuries the vast walled-city of Timbuktu, has always been synonymous, in Western minds, with the distant other, the dark heart of Africa. The fabled 'City of 333 Staints, was also, once, the hub of the camel caravan trading routes that criss-crossed Africa and a centre of Islamic learning that played a pivotal part in the spread of Islam across the continent. The arch-enemies of modernity are at war with their own traditions, just as its arch-exponents are in thrall to an ignorant Orientalism.

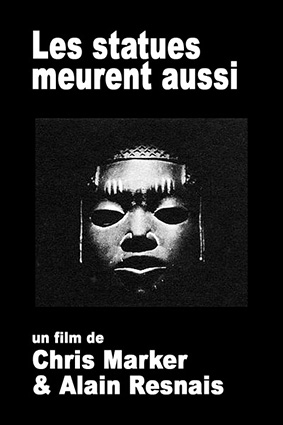

Sissako's facility with metaphor and understated virtuosity are grounded in deep knowledge of film history. The scene described above, for instance, recalls Chris Marker and Alain Resnais' Les statues meurent aussi/Statues Also Die (1953) – an early essay film, shot when Mali was still French Sudan, that interrogated colonialism using a series of African icons. Perhaps Sissako saw it during the decade he lived in Moscow, while studying at VGIK, the Institute of Cinematography – as the likes of Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Sokurov and Tarkovsky had before him. Perhaps his producer Sylvie Pialat (widow of the mighty Maurice Pialat), pointed him toward the film after his move from Mali to cinephile France.

Be that as it may, it's well-nigh impossible that Sissako was unaware of Marker when shooting Timbuktu. Marker, after all, nurtured a generation of African filmmakers while establishing the Insitut du cinéma in Guinea-Bissau and he explored African liberation struggles time and again in his films, notably in Sans Soleil/Sunless (1983). Another early scene in Timbuktu seems to confirm Sissako's familiarity with Marker's work. The film is bookended by scenes in which Jihadists hunt down an antelope. Sissako is surely paying homage to the famous closing sequence in Marker's Le fond de l'air est rouge/A Grin Without a Cat (1977), in which the hunting of wolves operates as a metaphor for political repression.

It has been complained that Sissako humanizes Jihadists and that his own Muslim beliefs persuaded him to go easy on them. Even if that were true, such an approach would still, surely, weaken the positions of Islamophobic propagandists in the West and 'hate week' Jihadists in the East, so, so much the better. Sissako may not recognise his own faith in Ansar Dine, al-Qaeda, Basij, Boko Haram or Hezbollah but, given that he has a masterly touch with the fine details of personality and psychology, the Jihadists might recognize themselves in Timbuktu. Perhaps. The tragedy is that they're no more likely to see it than mainstream audiences here.

Sissako's films are of a kind imagined by the late Stuart Hall when he considered emergent national cinemas. Films are not, he said, mirrors of reality but, rather, a "form of representation able to constitute us as new kinds of subjects, and thereby enable us to discover new places from which to speak." Initially envisioned as a documentary, Timbuktu uses fragmentary narrative techniques to quasi-documentary effect. Like the best documentarians, Sissako raises questions he may not have intended to. What does it say of Western culture that this film has probably generated more column inches here than the problems it highlights? What does it say of African culture that it won't reach wide audiences there because they have so few cinemas? Sissako says Timbuktu is alone among his films in making him cry and that he's cried several times while watching it. This reviewer could cry that such a beautiful and powerful film won't find a place in African hearts and minds.

|