|

If you've not been following the involvement

of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank in

the failing fortunes of the many countries that make up

the African content, then I'd certainly advise you to do

so. It's a grim story of exploitation and almost criminal

economic advantage-taking wrapped in the deceptively friendly

glove of financial support. Loans were granted to the world's

poorest nations by the richest, but with the sort of strings

attached that seem designed to exploit the recipients as

a source of cheap labour and goods, with forced privatisation

paving the way for foreign multinationals to undercut local

businesses with their own subsidised imports. If this were

not enough, many of the countries have had to spend

a far larger portion of their GNP on loan repayments than

on health care, which has been cited as a key contributor

to the continent's AIDS explosion. It's this socio-economic

issue that's at the heart of Abderrahmane Sissako's Bamako,

an unusual but elegantly handled blend of evidenced fact and drama.

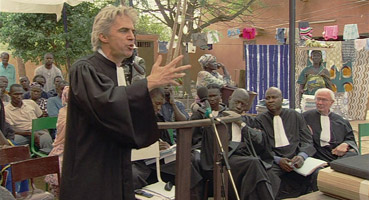

In

the Mali capital of Bamako, the relationship between bar

room singer Melé (Aïssa Maïga) and her

unemployed husband Chaka (Tiécoura Traoré)

has become strained. As the pair go about their daily life,

barely communicating with each other, the courtyard of their

house becomes host to legal proceedings in which the International

Monetary Fund and the World Bank are being prosecuted for

the harm their policies have inflicted on Africa, with witnesses

called to give evidence and answer interrogation from both

councils.

Now on paper I have no doubt that this sounds worthy but

cinematically a little dreary and even monotonous, and even

as someone who strongly supports the views being expressed

here I went in wondering whether this could actually work

as cinema. But from its earliest moments there is a gentle

poetry to the handling, and it soon becomes evident that

Bamako is going to be much more than a

platform for political rhetoric. The trial itself is slow

to get under way and at first appears to be taking place

on a different plane of existence to the everyday activities

that surround it. The locals indifferently go about their

business and although the proceedings are being conducted

in her own courtyard, Melé walks through it and the

assembled group without either party acknowledging the presence

of the other. Only the man guarding the entrance to the

yard appears to be initially aware of both worlds, greeting

Melé as she leaves and controlling access to the

court. He warns a camcorder-wielding reporter that no filming

is allowed, but professional cameras and mike booms are

openly in attendance – it's never certain whether these

are the instruments of a televised broadcast or Sissako's

own crew, revealed in a further peeling back of film reality.

Such

structural game-playing is always more than surface surrealism

and is clearly designed as a commentary on the relationship

that the average citizen has with decisions of state and

international politics. Initially unresponsive to the proceedings,

the townspeople begin to pay more attention when the arguments

heat up and the stories become more personal. But it doesn't

last. Indifference once again sets in, and the loudspeakers

over which the trial is being broadcast are disconnected by locals so that conversations

about more trivial matters can continue undisturbed.

The

location of the hearing also has an equalising effect, rightly

suggesting that the lives of ordinary citizens are as significant

and worthy of our attention as the debates of the even highest

court, something the judge here acknowledges with the announcement

that there will be "an adjournment for social realities"

to let a wedding party pass through. The quietly deteriorating

relationship between Melé and Chaka also has its

allegorical aspect, and even the most offhand moments can

double as social commentary: the unhelpful imported religions;

the reporter who bribes the gate keeper to gain access to

the trial; the man who is learning Hebrew to be a guard

at an Israeli embassy that there are no current plans to

build; the well-to-do defence attorney who demands to see

the logo that proves the sunglasses he is buying from a

street vendor are genuine Gucci.

At

the core, of course, is the case against the IMF and the

World Bank, which is passionately and persuasively made,

the dramatic structure of the film allowing an anger that

might feel overly didactic in a straight documentary. The

facts and figures presented are damning in themselves and

the indignation of the witnesses clearly comes from the

heart – unlike the main players and even many of the background

characters, they are clearly not professional actors but

Malian citizens with experience-formed views and their own

stories to tell. The case is intelligently and forcefully

argued by council and witnesses alike, but somehow the most

powerfully affecting moment is also the least specific,

as an old man sings in a voice filled with a sadness and

anger, in a dialect that neither we nor the court members

understand (there are no subtitles for this sequence), but

whose effect is to move us as profoundly as it does the

assembled group.

Bamako

is impassioned but well argued political cinema that also

succeeds in artistic and dramatic terms. It's typical of

the best recent African cinema in that it grips without ever

feeling the need to hurry and makes even its most inspired

moments seem unforced. Only the mid-film American Western

parody, complete with title and credits and starring co-executive

producer Danny Glover and directors Elia Suleiman, Zeka

Laplaine, Jean-Henri Roger and Sissako himself, feels a

little heavy-handed in its allegory. But in all other aspects

Bamako strikes a most effective balance

between subtle suggestion and direct confrontation, with

the anger of the witnesses and prosecutors both understandable

and appropriate. If you are familiar with the politics of

African poverty then Bamako still has plenty

to offer in its drama, its focus on the detail of everyday

lives, and its infectious sense of international solidarity.

If, on the other hand, you are looking to expand your understanding

of an issue that despite affecting an entire continent just

never seems to make the headlines, then this is a solid

and heartfelt place to start.

Framed

1.85:1 and anamorphically enhanced, this is a fine transfer

whose sharpness is free of obvious edge enhancement and

whose colours, which are vivid when they need to be (fabric

drying is a prominent background activity), are bright but

natural and do not feel artificially saturated. Even at

night the detail is clearly visible and the blacks here

are absolutely solid. Whether Bamako was

shot on film or Hi-Def I've been unable to confirm, but

the latter would account for the rare white-outs on the

some brighter spots in some shots. The occasional hazy look

is due to a combination of light, dust and insects and was

also that way on the film print.

Both

Dolby 2.0 stereo and 5.1 surround are available but there's

little to choose between them. Both offer clear, full bodied

reproduction of dialogue – there's not much in the way of

incidental music and the sound effects, with one deliberately

jarring exception, are largely consigned to the background.

The song sung by Melé that bookends the film sounds

particularly good on both tracks.

Interview

with Abderrahmane Sissako (35:41)

Becoming a standard but always welcome feature of Artificial

Eye discs is a half-hour interview with the director, and

this one with Abderrahmane Sissako covers some typically

useful ground, including Sissako's early life and film education

at the Soviet Union at the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography,

at which Sergei Eisenstein and Vsevolod Pudovkin once taught

and whose previous students include Sergei Bondarchuk, Andrei

Tarkovsky and Aleksandr Sokurov. He also discusses the film's

structure, intentions and casting, the western sequence

and the difficulty in distributing the film on home turf.

Interview

with Danny Glover (7:37)

The Hollywood actor and co-executive producer of this film

talks about working with a director he greatly admires,

and becomes infectiously passionate about the issues the

film confronts.

Christian

Aid Promotional Film (3:08)

Pete Postlethwaite, Adjoa Andoh and Ronan Keating outline

the problems created for poor countries by IMF and World

Bank in a level-headed appeal for action.

Trailer

(1:19)

A good sell that nonetheless suggests a faster paced film

than you get.

Stills

Gallery (1:31)

A rolling gallery of film stills displayed within the angled

framework of the menu design and of little real interest

when you have the feature to look at.

Director's

Statement

A textual feature in which Abderrahmane Sissako outlines

the political situation that provided his motivations for

making the film.

There's

also a brief Abderrahmane Sissako Filmography.

A

bold and effective approach to political filmmaking that

is nevertheless unlikely to work for everybody – we lost

one patron from our cinema screening just half-an-hour in.

But it deserves to be seen and its message appreciated,

understood and, in an ideal world, acted on. There are a

number of sites where you can find more information on the

issues raised in the film: The Africa

Action and Global

Issues sites should get you started.

Another

fine DVD from Artificial Eye that compliments the film with

a very reasonable package of extra features.

|