"Our image of happiness is thoroughly coloured by the time to which the course of

our own existence has assigned us. The kind of happiness that could arouse envy in

us exists only in the air we have breathed . . . A chronicler who recites events without

distinguishing between major and minor ones acts in accordance with the following

truth: nothing that has ever happened should be regarded as lost for history." |

Walter Benjamin, On the Concept of History, 1940 |

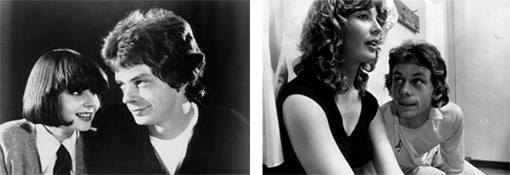

Olivier Assayas's face is delicate and firmly moulded, his head is long and narrow, the forehead is high, the eyes glint with assured intelligence. It's the face of a man who carries to the verge of his sixtieth year the energy and agility, the curiosity and sensibility of his youth. Something in the air we inhale during the breathless excitement of youth shapes our sensibilities for life. We may be more or less impetuous and impressionable in our formative years, but we're all of us marked by the attitudes and ideas we absorb as we edge toward the age of reason. There's considerable evidence in Assayas's films to suggest he was more attuned to his times as he grew up, and more intensely alive then than most. From his early post-punk pop shorts [Copyright (1979), Rectangle (1980), and Désordre (1986)] through to his arrival in the front rank of French filmmaking, he has consistently replayed the soundtrack of his youth. In his latest film, Après Mai/Something in the Air, Assayas returns to the early-1970s and the defining days of his adolescence, as he did in L'Eau froide/Cold Water (1994). Both these films recall his own first faltering steps toward maturity, both are peppered with scenes drawn from his own early experience, both revolve around rebellious teenage characters called Gilles and Catherine.

Each Gilles is clearly an Assayas alter ego; each Catherine is, presumably, modelled on his lingering memory of a teenage squeeze. These are but the most immediately obvious autobiographical aspects of these coming-of-age companion pieces. Assayas seems to spend a lot of time looking back on his young self, and his earlier films, and trying to puzzle out what shaped him. In both Cold Water and Something in the Air, Assayas looks back fondly on that intense time of life when everything seems possible and when, as Cassavetes repeatedly reminds us in Opening Night (1977), one's emotions lie "close to the surface." Assayas, though, is too serious-minded and shrewd to slip unwittingly into easy nostalgia and self-indulgent sentimentality. These films speak, with unflinching honesty, of the fragile certainties, disorientating confusions, and mutinous, libidinous energies of youth. There is nothing mawkish about either film. In both films, he depicts the pains and pleasures of adolescence, the styles and lifestyles of the early-70s with forensic precision and fine care.

Something in the Air is beautifully shot by Eric Gautier, masterfully edited by Luc Barnier and Mathilde Van de Moortel, and magnificently directed by Assayas. Clément Métayer plays Assayas's on-screen stand-in, Gilles, with easy-going excellence (in certain light and at certain angles he is the spitting image of Thin Lizzy's Phil Lynott), and the cast of non-professionals play their parts convincingly and intelligently. The costume designs of Jurgen Doering recreate the clothes of the early '70's to perfection. The film is as painstakingly researched as any heritage film. With the able assistance of all concerned, Assayas exquisitely evokes the atmosphere of that seldom-celebrated period as few have before, while remaining critical of it. As he has said: "The '70s are either ridiculed or romanticized, and both are wrong." Something in the Air, though, is much more than another loving exercise in nostalgic personal recollection and painstaking period recreation.

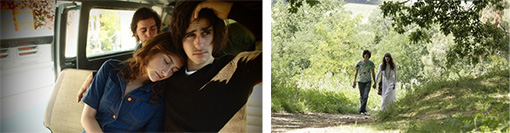

In Something in the Air, Assayas goes beyond the familiar markers of the period: the denim flares and floaty dresses, the narcotic haze of hard and soft drugs, the tie-die t-shirts and VW Camper vans. Here, as the film's superior French title suggests, he puts political flesh on the bones of wistful nostalgia, as he did in Carlos (2010) – his epic tale of Venezuelan revolutionary-turned-gun-for-hire 'Carlos the Jackal'. In touching on the desperate turn to violence of an impatient section of the defeated left, Assayas's latest film also operates as a companion piece to Carlos. Both films represent an attempt on his part to "dismantle events and reveal them from the inside out." In this more recent pair of films Assayas's determination to rescue the '70s from the enormous condescension of posterity leads him to layer political context onto autobiography. Carlos, as surely as Cold Water, can be seen as a counterpoint to Something in the Air, indeed, there is a case to be made for grouping all three films as a coherent '70s trilogy. Taken together, these three films show how the euphoric idealism of the '60s shaded into the darker realities of a later world in which, as Régis Debray once said, "the bourgeoisie still disgusts us but the Great Day has been and gone."

Something in the Air is set in France and Italy over one long hot summer during which the scent of grass is in the air and there's no sense winter will return. It is a song of tristesse and truth carried on a refreshing summer breeze. The film focuses, unsurprisingly, on Assayas's alter ego Gilles. It is built around his transient affairs with apolitical bohemian Laure (Carole Combes), his girlfriend as the film begins, and more grounded fellow student, Christine (Lola Créton), who he meets through politics. Both actresses are superbly cast, particularly Créton – a dead ringer for the Isabelle Huppert of La Dentelliere/The Lacemaker (1974). Both characters are completely convincing while embodying contending ideas. The ebb and flow of these fragile relationships underscores not only the easy-going sexuality of adolescence, but also Gilles' fluctuating interest in painting, poetry, politics, and, finally, film.

Somebody, I forget who, once coined an astute and amusing adage to describe the differences between the British and the French: the practical Brits tend to ask, "That's all well and good, but does it work in practice?" while the more cerebral French might be inclined to ask: "That all fine in practice, but does it work in theory?" A wonderful scene in Bill Forsythe's coming-of-age comedy Gregory's Girl (1981) serves to gloss that observation and demonstrate the related differences in the ways Assayas and Forsythe handle teenage romance. The film's hero, Gregory (John Gordon Sinclair) has developed a summer crush on a pretty but disinterested girl, Dorothy (Dee Hepburn), while another equally beautiful but more discerning girl, Susan (Clare Grogan), has fallen under the spell of Gregory's boyish charms. After Gregory plucks up courage to arrange a date with Dorothy, the two girls conceive a switch plan to divert and deliver the unwitting Gregory into the eager arms of Susan, with the help of two friends. Two awkward, sexually frustrated boys observe a game of pass the parcel as Gregory is collected from the date venue and delivered first by one, then by another girl to the waiting Susan. The astonished boys are filled with wonder at what they perceive as Gregory's predatory prowess; one repeatedly says: "There's definitely something in the air tonight Charlie."

That perfectly executed scene is as poignantly charming as it is funny and true. Something in the Air represents its own world with the same respect, accuracy, and authenticity. Assayas, though, handles the unselfconscious innocence of awakening sexuality differently: partly because of class differences, partly because of concomitant differences in intellectual climate, he does so with less humour and more seriousness than Forsythe. Gregory's Girl is set in a recognizably working class world that recalls two darker classics of British cinema: the childhood Trilogies of Bill Douglas and Terence Davies; and two similar classics of French cinema: Maurice Pialet's L'Enfance nue/Naked Childhood (1968) and François Truffaut's Les quatre cents coups/The 400 Blows (1959). Assayas's film, on the other hand, is set in a bourgeois milieu that recalls Bernardo Bertolucci's Prima della rivoluzione/Before the Revolution and Phillipe Garel's Les amants réguliers/Regular Lovers (2005). Assayas's characters – unlike those of Davies, Douglas, Forsythe, Pialet, and Truffaut – have cultural capital; his characters can move comfortably around ideas and ideologies in ways theirs cannot.

In Something in the Air, haute bourgeois Laura leaves for London and eventually succumbs to heroin addiction, politicized Christine remains loyal to the revolution, both drift away from Gilles into the arms of older men. The two young women speak to two contending sides of Gilles, his painterly aspirations and political convictions: ethereal Laura is Gilles' artistic muse; engagé Christine is his political conscience. Gilles feels sincere affection for both girls but wavers between the two, just as he vacillates between politics and self-expression. Gilles is too caught up in his own indecisive search for identity to commit to even teenage romance. Like Fabrizio in Bertolucci's Before the Revolution, Gilles is drawn to the romance of revolution but cannot commit to either revolution or romance; like Fabrizio, he merely dabbles in politics and love in the spirit of youthful experiment. Fabrizo talks about his "nostalgia for the present," the intense experience of the moment combined with realisation of its passing; Giles says something similar, he can't respond to reality because it's passing too quickly. Here class differences fall away to reveal a universal truth about the way we experience time in our teens. Although Something in the Air revolves around Gilles, Laura and Christine, the film's minor characters are as important as them in building what Assayas has called a "collective portrait" of his generation. He skillfully interweaves the personal and the political, the autobiographical and the historical, to describe the aesthetic and ideological disputes of the early-70s – all through a cast of characters who are both credible and emblematic.

In Assayas's latest film, love is in the air all right, but so, still, is revolution. He adds extra edge to his thematic concern with lost innocence by considering the 'desolate years' after the euphoria of May '68 – that revolutionary moment when Paris was the epicentre of international revolt, and when 10 million French workers followed the lead of the student movement to forge the largest general strike of the 20th century. It isn't just the mood and mores of our era that mark us in our minority; we're also defined by the extent to which we accept or reject the values of the epoch preceding our own. Like Assayas himself, the student radicals at the heart of the film were too young to participate in les événements de mai, but they have embraced the utopian ideals of May '68 and rejected the values of an earlier age – the values of old guard France, of reactionaries such as Raymond Marcellin, Maurice Papon and Marshal Pétain. Assayas grew up during a time when revolution was in the air, a time when, he says: "Everything was defined by how you positioned yourself politically. Right around the corner was a major change in society, the revolution. It was not a matter of if, it was only a matter of when, and of how to get it right when the past had gotten it wrong."

Assayas establishes his historical terrain and declares his political sympathies from the outset. We first meet Gilles at school, scratching the circled A of Anarchy on his desk as he half-listens to an earnest teacher deliver a lecture on orthodox Marxist history. The implication is that Gilles and his generation have lost interest and begun looking beyond Marx for answers. The film's first set piece recreates the riot that took place on 9 February, 1971, in Place de Clichy in Paris, during a demonstration called by the Maoist group Secours rouge (Red Aid) in support of their imprisoned comrades in La Gauche prolétarienne (GP/The Proletarian Left) – many of whom were on hunger strike demanding free speech and political status. During that demonstration, a 24 year-old Maoist, Richard Deshayes (whom Assayas thanks in the credits), was defaced and partially blinded by a tear gas grenade. An innocent apolitical student, coincidentally called Gilles Guiot, was arrested on his way home from the demo, scapegoated, and sentenced to six months in prison.

The Place de Clichy demo, which occurred as the revolutionary left prepared to celebrate the centenary of the Paris Commune, can be seen, with the benefit of hindsight, as a symbolic turning point for many on the French left. For those who refused to accept that the breach in history (or 'gap in reality') opened by May '68 had closed, the incident inaugurated a new phase of militancy that lead to armed struggle and Action Directe. For disillusioned revolutionaries like Régis Debray and Daniel Cohn-Bendit on the other hand, the incident signalled the need for reform of the mediatory mechanisms of civil society and coincided with a shift toward electoral politics – the first step on what Rudi Dutschke called "the long march through the institutions." Assayas doesn't consider that reformist tendency in the film, but, without laying things on too thick, he painstakingly picks out the ideological perspectives of various revolutionary groups active at the time.

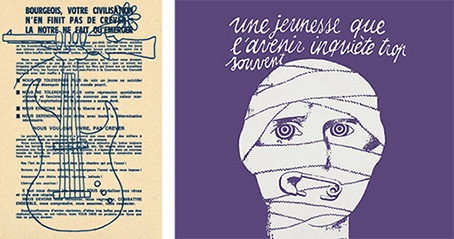

Gilles and fellow students Alain (Félix Armand), Christine, and Jean-Pierre (Hugo Conzelmann) respond to the Place de Clichy demo with a nighttime protest raid on their school. They spray it with slogans demanding the dissolution of the hated police Brigades spéciales d'intervention (who were responsible for Deshayes's injuries), declaring their admiration of anarchist leaders Durruti and Makhno, and proclaiming their affiliation to Vive la révolution (a short lived splinter group that fused 'anarcho-spontaneism', Maoism, and tier-mondisme/Third Worldism). After the raid we see Gilles at the school gates handing out copies of the polychromatic VLR paper, Ce que ne voulons: TOUT!/What We Want: Everything!, which, despite being edited by Sartre (who also edited the Maoist papers La Cause du peuple and J'accuse), was the most irreverently anarchic paper of the radical free press. Assayas's attention to the minutiae of radical politics is as understated as it is unusual. Close scrutiny of the film's rich textures, though, reveals the pointillist details that coalesce to form a striking portrait of Assayas's generation and the largely forgotten world of the French left in the aftermath of May '68.

Although Something in the Air seems to have its feet planted firmly in 1971, it effectively condenses events that took place over several years into a single summer. By tracing the lives of Alain, Christine, Gilles and Jean-Pierre over a short period, Assayas hints at the broader political journey of a generation of young radicals 'après mai'. After Jean-Pierre is implicated in the graffiti raid by security guards and subject to internal school discipline, the group return to the school in a reprisal attack on the guards. Gilles throws a Molotov cocktail at their hut and one of the chasing guards is injured when Jean-Pierre inadvertently drops a sack of cement mix on his head. When the authorities initiate a second, more serious investigation, an experienced militant, Rackman le rouge (Martin Loizillon), advises the group to lie low.

Gilles, Christine and Alain head to South to Italy with a group of militant filmmakers. Alain, an aspiring painter like Gilles, meets a group of rich American hippies and falls in love with Leslie (India Salvor Menuez), an aspiring dancer. Again, these characters are emblematic of tendencies within that (middle-class) generation. The individual journeys of Assayas's characters, and their trip to Italy, represent the wider journey taken by Assayas and a generation of radicals. The film collective calls to mind Chris Marker's SLON (Service de lancement des oeuvres nouvelles) co-operative; Godard's Dziga Vertov Group; and, when Gilles and co connect with militant workers in Italy, the Besançon Groupe Medvedkine – described by Trevor Stark, in his book Cinema in the Hands of the People, as one of postwar Europe's most significant experiments in cultural production 'from below'. Again, this is no accident. There is very little in Something in the Air that is accidental or extraneous. Those knowing references to film history reflect Assayas's knowledge of cinema, but there are, as there tend to be in his work, autobiographical allusions present.

Assayas often refers back to references in his earlier films: in Irma Vep (1996), he pays homage to Louis Feuillade's silent series Les Vampires (1915-16) but also to the SLON-Medvedkine collective, whose Classe de lutte/Class Struggle (1969) lingers on the screen. In another autobiographical aside, Gilles asks one of the filmmakers if he can borrow a camera (he is told the collective tend to lend only for agitprop work); Assayas made his debut short, Copyright, with a camera borrowed from Mark Karmitz, founder of MK2 but a militant filmmaker in the early '70's. Assayas knows cinema well enough to feed such references into his film effortlessly: he has written regularly for Cahiers du cinema, ever since being recruited by Serges Daney and Toubiana in the '70's; he subsequently succeeded them as Editor of Cahiers; and he has sat, for long spells, on the board of the Cinémathèque française.

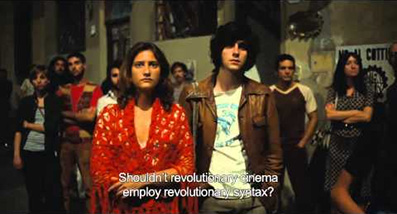

Among other things, Something in the Air, like Irma Vep, is a film about film and about filmmaking. It pays homage to Philippe Garel's Regular Lovers, contains scenes in which the collective present an open air screening in Italy, presents on-screen excerpts from radical films of the period, and effectively ends with Gilles watching an experimental film ('starring' his old flame Laure) in the Electric cinema on Portobello Road. The knowing references to film history are far from self-indulgent; they contribute to Assayas's "collective portrait". It is through the skilful application of layers of such details that Assayas builds up his picture of the aesthetic and ideological landscape of the period. It is by detailing the ideas Gilles and his friends absorb and reject along the way, through their choices and conversations, that Assayas paints the broader canvas. It is, therefore, only by examining the film's intricate details that we can follow Assayas's cinematic journey and recognise how it mirrors the left's collective shift from revolutionary struggle to cultural politics in the early '70's.

Something in the Air is set within that period (roughly 1969-1974) when, hard though it to believe now, Maoism found favour on the French left (notably with intellectuals such as Badiou, De Beauvoir, Foucault, Godard, and Sartre). De Beauvoir said: "Despite several reservations, especially my lack of blind faith in Mao's China, I sympathize with the Maoists . . . whereas the entirety of the traditional Left accepts the system, defining themselves as a force for renewal or the respectful opposition, the Maoists embody a genuinely radical form of contestation." Les Maos compared themselves to the Resistance and bracketed the counter-revolutionary Parti communiste français (the P"C"F as they called it) with the occupying powers of Gaullism and capitalism. Their view is encapsulated in the slogan: "Please leave the Communist Party as clean on leaving as you would like to have found it on entering." [Pialet's Naked Childhood begins with a scene that reminds us that working class support for the PCF, the party of the resistance, remained strong in this period]. This was a time – after the Sino-Soviet split, before the full horrors of the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution hit home – when Maoism, with its emphasis on the importance of moving among the people and its refusal of the separation of manual and intellectual labour, suggested a way forward that might unite students and workers. Maoism also, albeit briefly, seemed capable of reconciling and reviving the Marxist-Leninist and French revolutionary traditions.

Although Assayas appreciates such historical realities, he has declared his hostility to the Maoist moment in French radical politics. He had good reason to be suspicious of totalitarian political tendencies. His father, Jacques Rémy, an anti-Fascist and anti-Stalinist militant, had been forced to flee Vichy France, despite having changed his Jewish name to avoid detection. His mother, Catherine Rémy, was a Hungarian aristocrat who fled her country when the Soviet-backed regime took over in 1947. The film's autobiographical underpinnings and precise details always illuminate history and politics: in the film Gilles reads Gregory Corso, George Orwell, and Simon Leys' landmark work of 1971, The Chairman's New Clothes: Mao and the Cultural Revolution. While driving to Italy, Gilles stands his ground when one the filmmakers tells him to watch what he reads and declares Leys' book to be CIA propaganda. It's easy to see why Assayas/Gilles describes the collective's politics as primitive. This is typical of Assayas's attentiveness and his way of illuminating his characters' personalities through their political positions, and vice versa.

In the internecine disputes that bedevilled the frère-ennemis of the fragmented French left in the early-70s the group to which Gilles and his friends belong, VLR, steered a course between Anarchism and Maoism. The group saw sexual liberation, pop culture, and student resistance to an authoritarian education system as forms of political struggle as valid as wildcat strikes, factory occupations, and resistance to police violence. Their anti-authoritarian, anti-doctrinaire position is summed up in the Situationist slogan "Those who speak about revolution and class struggle without referring explicitly to everyday life, without understanding what is subversive about love and what is positive in the refusal of restraints, such people speak with a corpse in their mouth." In the VLR, the Situationist critique of everyday life dovetailed with Maoism's challenge to Stalinist orthodoxy.

As Something in the Air hits its stride, Assayas's interest in Situationist ideas comes to the fore. At the beginning of the film Gilles is reading TOUT!, by the end of it he is reading counter-cultural broadsheet IT and Situationist texts. Again, Assayas's own journey and that of his generation merge. Situationism's resistance to alienation and insistence that "boredom is counter-revolutionary" squares with Assayas's desire for a full, unfettered life of creativity, but it has also affected his filmmaking. He has frequently declared his debt to two figures: Robert Bresson and Guy Debord. In his book Une adolescence dans l'après-Mai. Lettre à Alice Debord Assayas says: "Aren't film shoots . . . situations to some degree? Don't they amount to conscious interventions in the domain of daily life?"

As ever the details are vital: Kevin Ayers, Nick Drake, Soft Machine, The Nice, Hendrix, Page, Zappa et al. are not here to make up the numbers and sell a soundtrack CD. By the early '70's many of the soixante-huitards who had once decried rock and pop as soporific, bourgeois pollutants, counter-revolutionary excretions of false class consciousness, now saw those forms as a means of connecting with working class youth. As Cromwell, perhaps with the Levellers in mind, said: "You never go so far as when you don't know where you're going." The left had gone far (De Gaulle and the PCF said it had gone too far), now it had to find its feet again. Free concerts, cultural interventions, and sexual liberation soon came to be seen by many on the revolutionary left as a means to a political end. To harness situations and 'collective joy' for the revolution was the new project. It was always a likely route for middle-class radicals after the 'return to normal' and the exhaustion of revolutionary proletarian energies. Writing about May '68 in La Prise de parole (The Capture of the Word), Michel de Certeau says: "In May we captured the word as the Bastille was captured in 1789." Régis Debray would later rephrase de Certau, suggesting that the defeated left would "go down into the street en masse to capture words as compensation for the Bastille and to present a student rag as a form of revenge."

If the politics in Something in the Air has the feeling of a student prank, that is only to be expected; these are students after all. Giles doesn't tread the well-travelled path of the middle-class radical: he doesn't scweam, grow bored, and throw his toys out of his pram when revolution doesn't fall from the trees, like a juicy apple, into his hands. He simply faces facts, turns, and heads for familiar ground. While frustrated and desperate die-hards turned into the cul de sac of armed struggle, another movement of militants shifted into cultural struggle. Assayas was clearly in the latter camp. At any rate, his own journey and that of his alter ego mirror each other.

After the trip to Italy, Gilles works briefly for his father, a scriptwriter afflicted by Parkinson's disease who needs his help. Again, parallels are strikingly obvious. When Assayas was a student he worked for his own father he fell ill. Towards the end of the film, Gilles attends a house party on the invitation of Laure. The party is held in a large country mansion reminiscent of (if not identical to) the one in Pillippe Garel's Regular Lovers, and not dissimilar to the one in Cold Water in which a group of students take drugs and dance around a bonfire to rock music from Assayas's youth, as they do in Something in the Air. At this latest house party Laure jumps from a top floor window to escape a fire, presumably stone, doubtless to her death. Christine, meanwhile, is still working for the revolution and finding her ideological bearings by frequenting feminist cafés. Gilles heads to London having found work as a runner at Pinewood, on a schlocky film about Nazis and dinosaurs (Assayas himself served his apprenticeship as a gofer on Richard Donner's Superman). It's all a long way from the demonstration in Place de Clichy. By the film's end, as Gilles' search to find himself is resolved in favour of film, self-expression has trumped collective commitment, and political aspirations have given way to career aspirations.

If Something in the Air seldom replicates the orgasmic potency and adrenaline-fuelled impatience of revolutionary youth, it has more to offer than politics as remembered by a middle-aged, middle-class aesthete through the medium of a cinematic alter ego. It is testimony to Assayas's achievement that Something in the Air does not look embarrassingly out of place among that select group of films to chart the aftermath of May '68. When one considers the importance of May '68, and the thousands of films that have poured forth in the interim, it is astonishing that the period after les événements has been covered by so few films. Perhaps the pain was too great. The period was covered in three great documentaries: Romain Goupil's Mourir à trente ans/Half a Life (1982), Chris Marker's Le fond de l'air est rouge/A Grin Without a Cat (1977), and Hervé Le Roux's Reprise (1997). Assayas's film sits in the select company of three great fiction features that have boldly gone where others feared to tread: Jean Eustache's La maman et la putain/The Mother and the Whore (1973), Philippe Garel's Les amants réguliers/Regular Lovers (2005), and Alain Tanner's Jonah Who Will Be 25 in the Year 2000 (1976).

Interviewed by Cahiers du cinéma, Alain Tanner responded to a question about the "survivors" of the "shipwreck" of May '68 by saying that les événements "brought out hopes and caused hidden desires to flower which have been on the surface ever since." Jonah, he said, was about those hopes and desires not those survivors. Something in the Air shows what happened to those hopes and desires in the period 'après mai'. Assayas's penetrating eye for detail results in a beautifully crafted collagist picture of that period and an unflinchingly honest "collective portrait" of his generation. Assayas has mined his own youth for material and meaning as effectively as Davies, Douglas, Pialet and Truffaut. In Something in the Air he offers insights into the aftermath of May '68 as penetrating as those provided by Eustache and Garel while treating the much-mocked early '70's with profound understanding and rare respect.

Forthcoming screening at the National Film Theatre:

July 10, 2013 8:40 PM

July 11, 2013 8:40 PM

July 12, 2013 6:00 PM

July 13, 2013 4:00 PM

July 14, 2013 8:40 PM

July 17, 2013 6:00 PM

|