| |

“And Jeff [Jeff Goldblum] had an upright piano brought onto the set and he would be playing it, standing up playing ragtime on the piano and singing, and declaiming at the top of his voice from a P.G. Wodehouse paperback anything, anything to deflect his mind from the fact that I'm about to do a take, so that when I would say, "Action," he would throw the paperback away and there would be this flood of adrenaline into his head, which he used. And Tim Pigott-Smith would be trying keep up with this and remember where his mark was. But it was wonderful because that was exactly the dynamic between the two characters.” |

| |

Director Mick Jackson* |

Note: Life Story is available on BBC iPlayer in its best looking iteration I’ve found so far.** I’m not sure how long it will stay online but if you get anything out of my review that piques your interest, add yourself to its many fans. You’re in for a real treat.

Life Story has so many small but potent pleasures, I really don’t know where to start. I am one of a very small group of people who’ve seen the film actually projected. When I started working at the BBC, a colleague of mine, as a wonderful surprise, managed to get a 16mm copy of the film sent up from London to Cardiff which we screened just for us celebrating the completion of a short film on which we collaborated. It occupies a place on the highest level in my appreciation vaults where very few works ever ascend to. I rate it as the best television film I have ever seen for the exceptional quality of its screenplay, direction, music, sound, film editing and performance… In other words every creative on this film is at the top of their game. It is the very definition of a blessed gestalt, the sum of its parts creating a sublime whole. First, an overview of the narrative.

Based on the book The Double Helix: A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA by James Watson, Life Story introduces us to four scientists, all toiling on the same road heading for the same destination but some travelling a little faster than others. In the early 1950s, the Holy Grail of scientific discovery was to crack the structure of deoxyribonucleic acid, the building blocks of life itself. Biologically speaking, DNA is the architect of all living things on Earth. When your wheelhouse is at the molecular level, you’d think any attempt at filmmaking about the topic might be stymied by the infinitely small subject matter. Life Story is not about molecules in the same sense that Ted Lasso is not about football. It’s about people and what extraordinary people. The script offers just enough detail on the tasks these experts perform so while you may not understand what’s being done exactly, you understand how important the results are to those in the race. That is a rare screenwriting skill and William Nicholson uses his own considerable talent with some wit and style. He’s helped by intriguing close ups and camera movements that keep your attention even if you’re unclear regarding what you are being shown.

American James Watson is in Naples with his sister attending a seminar by a front runner in the field of genetic research, Maurice Wilkins. Maurice is so English, it’s a wonder he’s not wearing a knotted handkerchief. This socially awkward man is not equipped to deal with a forward, young American whirlwind and he is rescued by Watson’s sister physically steering her brother away from the poor soul. Based in Paris, a young English scientist, Rosalind Franklin, is heading to London to work with Maurice Wilkins. She has reservations. How can any city without patisseries possibly be worth living in? Braving the weather, a portent of more glum to come, she pitches up and almost immediately clashes with Wilkins, the man with whom she is supposed to be working alongside. Watson arrives at Cambridge University and finds to his delight that Francis Crick, ‘the bright hope’, has the same passion to go after the big questions because they need “…big answers!” It’s music to Watson’s ears when Crick mentions DNA… So begins the race between a united pair in Cambridge and a distinctly disunited pair in London. Franklin doesn’t see it as a race but is producing work that spurs Crick and Watson on to charge into the lead after a few embarrassing missteps.

Of course, the person most responsible for the quality of the work on any film is the director. They get the flak for a failure and more leverage and higher budgets for a success. After his successful TV work, it wasn’t a stretch to imagine Mick Jackson being lured to Hollywood. Hindsight can sometimes be a fog concealing or distorting reality but when I found out that one of Jackson’s first TV jobs was directing the first series of Connections with James Burke, I noted that the series’ visual style had the nascent stirrings of some of his creative contributions in later work. Watching the series as a thunderstruck child, I attributed the actual direction to the camera people because it looked so good. As we are lingering on the idea of ‘connection’ let me also credit Mick Jackson for directing in that series what you can find on YouTube as ‘The Greatest Shot In Television’. Check it out. It is utterly jaw-dropping. One more connection… Taking over from Jackson for series two in 1994 was Mike Slee, a director I worked with in 2023. We must also remember Jackson directed the superb ‘nuclear bomb goes off in Sheffield’ TV film Threads and the brilliant political drama A Very British Coup whose memorable first shot is urine hitting the toilet, a shot that American broadcasters would never have allowed for public consumption. Jackson’s Hollywood movie career gave us Steve Martin’s L.A. Story and the huge hit that was The Bodyguard. He later received some Emmy love too including ‘Outstanding Movie Made For Television’ for his biopic of a remarkable woman, Temple Grandin. So let’s say that Jackson’s role in the success of Life Story was probably major.

Helping him achieve that success is a cast so well suited to their characters, it’s hard to imagine anyone else in these roles. Jeff Goldblum is something of a one-off. Tall, wide-eyed and sporting mannerisms that tend to inhabit any character he’s playing, he’s only ever Jeff Goldblum. And it’s a constant surprise to me that his Goldblumminess never gets in the way of the character he’s playing. It’s like Connery never changing his accent despite playing a Russian submarine commander… Goldblum, now treating old age as another iconic cool career phase, is definitely the best Goldblum we have. He plays Watson as hyperactive, constantly chewing gum and focussed on the oddest of things which always make me smile. As Crick explains the nature of X-ray crystallography, Watson looks away from the drawing and seems to examine Crick’s left ear for really longer than necessary (at 53’ 32”). Goldblum, at this stage in his career, was carving out leading man status. A year earlier he’d starred in and as The Fly and was getting stellar reviews. How on Earth did Jackson snare a Hollywood leading man for Life Story? I’d like to think it was the script and a chance to work in the UK. Superbly counterbalancing Goldblum’s energy is Tim Piggot-Smith as Crick. It’s the less showy role but all the more important to keep the film grounded. This is a dramatised true story. What makes Piggot-Smith shine is his passion which is conveyed in a more concentrated form and one that only surfaces infrequently. It has to be said, the two men make a delightfully dynamic couple. In an altogether different relationship are Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins. The former – played heartbreakingly by Juliet Stevenson – is often misunderstood and rarely capable of correcting misconceptions about her character. When in the company of the French, she is warm, funny and relaxed. Stick her in London where it’s always raining and the trains are crowded with dour men and her defence shields snap up and rarely drop. She would have been known as a very new kind of woman in the early 50s, a ‘feminist’ which in that era meant something far more radical and to some, even odiously unpleasant. There’s a quotation from Watson in his book that the film is based on which would have him cancelled in a heartbeat. “The best home for a feminist is in another person’s lab.” Ouch. All there is, to ‘Rosie’ Franklin, is the work and without her work, Crick and Watson would not be so famous in scientific circles. Maurice Wilkins, the quintessential Englishman of his era is played by Alan Howard. Almost perpetually uncomfortable around Rosalind, he’s a lost man in his own department. It doesn’t help that he believes Franklin has the best DNA samples to play with. It’s these four powerhouse performances that are the beating heart of the film.

The rest of the cast, not to ignore then in any way, are uniformly excellent so let’s move on to other aspects. Peter Howell’s original score superbly drives the action forward and emphasises the emotion behind the few but profound moments of reflection. Created at the BBC Radiophonic Workshop (a romantic and well-loved name for old devices used to create new sound effects and music) it had the distinction of being very cutting edge at the time. Doctor Who’s very first iteration of its theme was created there too. See how well the score works accompanying Watson’s urgent tennis session with his sister (1 hr 28’ 59”). And then there is ‘Grand Choral’, a cue written for François Truffaut’s La Nuit Américaine (1973) by French national treasure George Delerue that is used to top and tail the film. It’s an inspired choice, once heard never forgotten. Let’s not forget the splendid sound design, from the ticking effect underlying some significant pieces of dialogue to the exaggerated wrenching squelch of an orange being torn apart. This film was sincerely loved by those that made it.

An aspect of the film close to my own heart is the superlative film editing by Jim Latham. An outsider can never know who was responsible for which creative decisions in the cutting room and it’s often left shrouded in ambiguity because the creative process is dynamic and organic. See the next paragraph for more on this mysterious process. One of the most creative aspects of any film is how it transitions from one scene to another. There’s the straight cut or a dissolve but getting from A to B can be playful, dramatic or challenging. Life Story is choc-a-bloc with fascinating transitions, so many that I’ll just point out a few of my favourites. About to deliver a metaphorical knockout blow to Wilkins’ assumption of DNA having an helical shape, Franklin prepares her pen. As she pushes the lid on to the bottom of the pen, we cut to a boxer’s arm completing the movement. A knockout blow. We are in Nic Roeg territory here (at 1 hr 08’ 06”). The arrival of a famous scientist’s son in his fancy car and all smiles is treated so playfully that I grin just thinking about it (1 hr 10’ 15”). The timing of the music and the sound effects is wondrous. My favourite for its humour and simplicity is at 10’ 59”. After Watson is told that his presence doesn’t cost the university anything, he delights at a female cyclist showing a bit of leg riding past and says “That’s right, I’m free!” smiling at his good fortune and the girl. Still on a close up of Goldblum, we hear a voice from the next scene say “I’m told you’re a birdwatcher!” Goldblum’s response to the unintended double-entendre is to look for the source of the question which is also timed perfectly. We cut to the man asking the question in his university office. The editing on this film is so clever, some of it invisible with liberal use of foreground wipes. With Watson alone jammed in on the floor next to bookshelves stuffing himself with oranges, we’re not even surprised when at 1 hr 30’ 33”, one cut takes us to both men from the shot of a scrunched up piece of paper. There is a smoothness to the editing that compliments Jackson’s camera movements which are many, varied and subtle. Even film dissolves, which I try to avoid using as they mostly feel lazy, all of them work in this film so well. I’m coming to the opinion that there is nothing in this film I do not appreciate and adore.

It is impossible to assign credit to individual minds working on the film for some of the most satisfying elements and there are too many to list. Did Nicholson indicate them in his script? Did Jackson fold them in with his mise-en-scene or were the actors responsible? What about the editor? With some of these transitions, I have to believe they were meticulously worked out, directed and shot and cut with precision. It matters little who came up with what. Those moments are there to interpret and enjoy. For a small example of nuance that, after twenty to thirty viewings, I’ve only just noticed, you don’t have to wait long. As mentioned before, Watson sends his sister ahead to butter up Maurice Wilkins in Naples. She finds out that Wilkins is practically blind without his glasses. He says “It’s better that way, sometimes.” As Watson comes charging in to the conversation, Wilkins is struck dumb by his brashness and it’s very clear he is intensely uncomfortable. He brings the meeting to an end in the subtlest of ways and Watson’s sister wordlessly accepts the cue and takes her brother away. What did Wilkins do? He took off his glasses… “It’s better that way, sometimes.” Just brilliant.

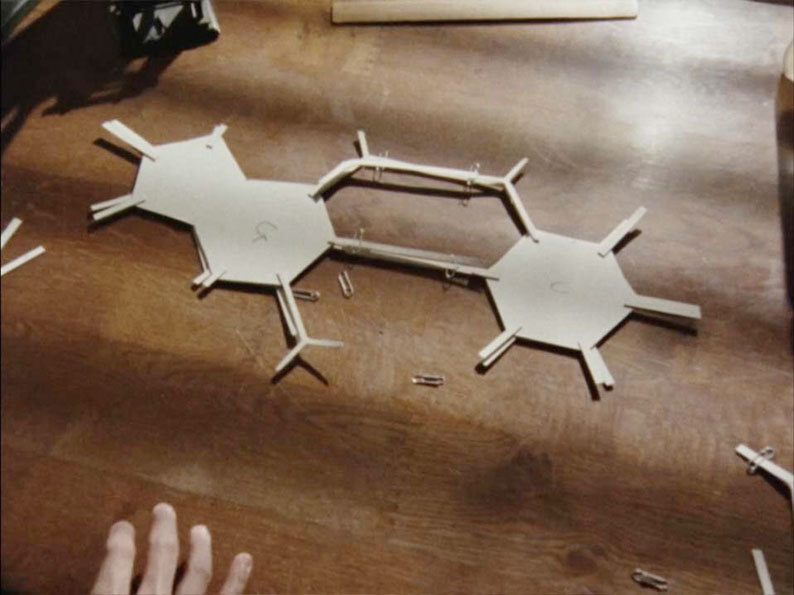

I’ll leave you with the last line of the film that seems to inform most creative endeavours delivered by Rosalind Franklin looking up at that extraordinary molecular skeletal model of DNA… “When you see how things really are, all the hurt and waste falls away. What’s left is the beauty.” Amen.

| A Postscript on What’s Out There Somewhere |

|

Life Story is a film almost perfectly realised. Dated by its 1.33:1 aspect ratio and existing for viewing only in standard definition is a crime against visual art. There are not many films that I would set up a crowd funder to unearth its original 16mm A & B cut negative, clean it up for scanning and create a Blu-ray for… But Life Story sits at the very top of my list. 16mm film is more than up to being scanned to a high definition format which is why it’s so infuriating to find copies of the film online as standard definition and dirty and in some iterations, somewhat washed out. It was never released on any format commercially in the UK despite winning ‘Best Single Drama’ at the BAFTAs in 1988 but the US Arts and Entertainment Network co-producer released a VHS and subsequent DVD designed primarily as a teaching aid. These rare beasts are commanding high prices on Ebay. Originally sourced, one imagines, from a 16mm print, the film runs 4 per cent slower than its UK version (as mentioned presently available on BBC iPlayer but not forever, folks**) due to its conversion to the American NTSC broadcast system. So a detail-rich 16mm film print was transferred, one assumes, to a master standard definition tape and then to the lowest resolution tape format (the DVD appears sourced from the same tape master – dust spots are in identical positions in frame. Trust me. I checked) and as such these copies have some film damage and look terribly washed out. Even the hallowed libraries of the British Film Institute*** only have standard definition tape masters. The Internet Archive has a few Horizon programmes available to download and Life Story is among them. Also from the same source, you can download a Portuguese hard coded subtitled version. I cannot even begin to guess where the original cut negative could be found. The frame grabs in this review were taken from the version available on the BBC website. I’ve not tracked down the physical DVD version or rather I have but cannot afford it! For the curious, the re-named film (Double Helix) is available here.**** Changing the name of the film itself plays havoc with research.

* https://www.dga.org/Craft/VisualHistory/Interviews/Mick-Jackson.aspx?Filter=Topics

** https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/m0025xxc/horizon-life-story-a-horizon-special

*** https://collections-search.bfi.org.uk/web/Details/ChoiceFilmWorks/150207265

**** https://films.com/title/7453 |