"The Coens are clever directors who know too much

about movies and too little about real life." |

Emanuel Levy, from Cinema of Outsiders, 1999 |

"Art films are not necessarily photography. It's feeling. If we can capture

the feeling of a people, of a way of life, then we made a good picture." |

John Cassavetes, from Cinéastes de notre temps, 1969 |

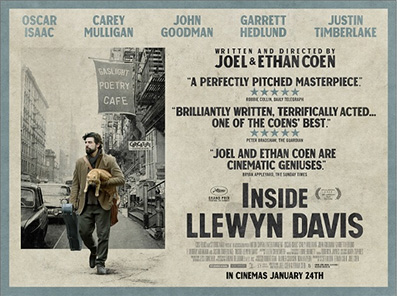

The American Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences may have snubbed Inside Llewyn Davis, but the Coen brothers' latest film had already earned a Grand Prix at Cannes before being named as Best Film of 2013 by the U.S. National Circle of Critics. Hell, what do critics know? Enough to recognise a good film when they see one. The Coens' reputation for excellence is deserved and reviews of their latest film have been overwhelmingly positive, and yet I hadn't planned to see it, far less to review it. The exalted brothers need no help from small fry like us to promote their productions and other, less heralded films called for attention more urgently. In addition, I’ve always felt there’s something soulless about the Coens’ work, for all their restless invention and admirable artisty. I acknowledge that our hunger for novelty is so acute that we become unjustly blasé about directors as prolific as the Coens. In their case, familiarity has bred, if not contempt, at least weariness in face of their tonal, stylistic, and thematic consistencies. Unfair perhaps, but not even appreciation of their daring diminishes my sense that those consistencies have hardened into cliché; nor has a taste for their humour altered my view of the Coens as talented cynics whose stylistic flair masks a lack of emotional depth. Their cynicism and flair are equally evident in Inside Llewyn Davis, which follows an angst-ridden aspiring musician on a circular journey centred on the Greenwich Village folk scene of 1961. A continuation of their thematic concern with isolated loners, it replicates the low-level misanthropy alluded to by critic Emanuel Levy when he said, in a review of Fargo: "The Coens have always treated their characters with contempt, ruthlessly manipulating and loathing their foolishness."

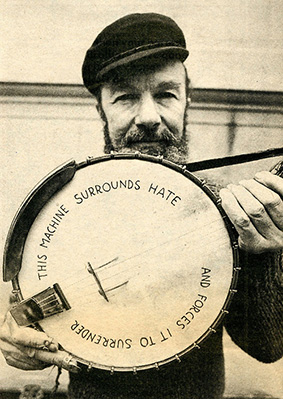

Having made my unease about the Coens plain, I'd best explain why I'm here. A few days ago, with time on my hands after a leisurely stroll beside the Thames; fancying a film, any film; I was drawn to Inside Llewyn Davis by its eye-catching poster, a fondness for folk music, winter weather, and the admittedly ditzy idea that there'd be a nice neatness to seeing a film set in Greenwich Village, New York in Greenwich Picturehouse, London. Life is full of coincidences and surprises. I left the cinema elated, surprised by how much I'd enjoyed the film, and then returned home to the searing, saddening news of Pete Seeger's death. A standard-bearer for the folk scene, Seeger was a man of unimpeachable integrity, who helped shore up the architecture of hope in a time of despair. Oboy will we miss him. I pulled his Strangers and Cousins LP from my shelves and, as the dear departed man's voice rang in my ears, I decided I must review the film; decided then and there, with tears in my eyes – tears not for Pete Seeger alone, but for all the folk giants who once walked our earth, for the likes of Ewan McColl, Phil Ochs, Hedy West, and Dave Van Ronk too. Sadly, Inside Llewyn Davis doesn't do justice to their memory. While it does a great service in rendering aspects of the folk scene in precise period detail, it is a sanitised pastiche of that scene not a distillation of its essence. If Inside Llewyn Davis were a folk song, it would be a polished poppy one by Peter, Paul & Mary bless 'em, not an earthy, engaged one by Woody Guthrie, may he rest in peace. Ultimately then, although I found the film captivating, I'm reviewing it to set the record straight, about the folk scene of the early sixties and about the much-manipulated-and-maligned Mr. Davis.

Another note is necessary here. Unable to begin my review until this weekend, I did manage to squeeze in a second viewing of the film in the interim, but by the time I'd gathered my thoughts on it, a fellow contributor to this site, Timothy E. RAW, had posted a review of it. Feck, I thought, and, well that's that! Later, I had second thoughts and decided to press on regardless. Tim's a terrific reviewer, but his mystifying passion for heavy metal (made public in his previous review, of Metallica: Through the Never) meant, inevitably, that his was an outsider's view of Inside Llewyn Davis, in more senses than one. Given my interest in the folk scene, I hope my review will complement and collide with his; given the importance of the Coen brothers, I hope our readers will forgive us for posting two reviews of the same slight but engaging film. Two for the price of one, as some say.

With fifteen feature films, six Oscars, and a Palm D'Or already behind them, the Coen brothers could have been forgiven for resting on their laurels. That's not in their nature though. The brothers have seldom stood still. They have consistently taken risks and constantly reinvented themselves. Rumours persist that their next film will star George Clooney as a silent era star cast in a film within a film, a 'sword and sandals' epic set in ancient Rome. Their work has tended to subvert Hollywood genres, in playfully postmodern ways. To paint with a broad brush, we might say they have vacillated between the visceral violence of either neo-noir [Blood Simple (1983), Miller's Crossing (1990), The Man Who Wasn't There (2001)] or the western [Fargo (1996), No Country for Old Men (2007), True Grit (2010)] and the gallows humour of screwball comedy [The Hudsucker Proxy (1994), Intolerable Cruelty (2003), Burn After Reading (2008)]. More precisely, we might say that elements of the gangster, noir, screwball, and western genres have more often than not mingled in the Coen cannon [Raising Arizona (1987), Barton Fink (1991), The Big Lewbowski (1998), Oh Brother Where Art Thou? (2000), The Ladykillers (2004), A Serious Man (2009)]. Theirs is a magpie cinema that thrives on, and revels in intertextuality, a cinema born of, and reliant upon knowing cinephilia and broad cultural memory.

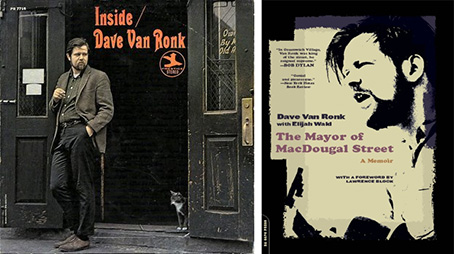

Throughout their career, the Coen brothers have drawn on literary sources (Dashiell Hammett, James M. Cain, Raymond Chandler, William Faulkner), on musical sources (Norman Blake, The Fairfield Four, Pete Seeger, The Stanley Brothers), and, obviously, on cinematic ones (Frank Capra, Ed Dmytryk, Howard Hawks, Preston Sturges). Their latest film is based a book, The Mayor of McDougal Street, a musician's memoir by Dave Van Ronk, a legendary figure on the folk scene, of whom Bob Dylan said: "In Greenwich Village, Van Ronk was King of the Street, he reigned supreme." It re-presents songs made famous by the likes of Brendan Behan, Ewan McColl, Cecil Sharp, and Hedy West. And it surely owes a debt to the cinéma-vérité-influenced films of John Cassavetes and Shirley Clarke; particularly Cassavetes' Shadows (1960) and Clarke’s Cool World (1964), both of which were shot in New York and which the Coens, as cinephile natives of the Big Apple, must have seen.

For Shadows, Cassavetes shot in 16mm to capture shimmering monochrome glimpses of the New York jazz scene at the tail end of its golden age, as clubs like Birdland closed and jazz retreated into poverty-stricken isolation. For Inside Llewyn Davis the Coens shot in 35mm to create a beautiful, muted Ektachrome look in keeping with their more remote recreation of the New York folk scene in 1961, just before folk took its turn in the spotlight and shortly before the advent of Bob Dylan, Simon & Garfunkel, and Phil Ochs. The film's cloudy, desaturated palette exquisitely replicates the wintery scene on the cover of Dylan's 1963 LP 'The Freewheelin Bob Dylan' – a visual touchstone for the film along with cover of 'Inside Dave Van Ronk'. That look underpins the film's melancholic mood as surely as the sadness that oozes from the folk songs performed, 'live', by its cast. The film opens with a faultless recital by Llewyn Davis (Oscar Isaacs) of Van Ronk's "Hang Me Oh Hang Me', with its repeated refrain "Poor boy . . . I've been around the world." The film's well-travelled and impecunious hero, who has stints in the merchant marine under his belt, is a "poor boy" all right: his father is dying, his mother is dead, his musical career and sense of self-worth are floundering, and he's all at sea after the suicide of his mate and musical partner, Mike Timlin, who, we learn, had thrown himself off the George Washington Bridge.

I remain mystified by reviewers' repeated characterisation of Llewyn as a feckless, dislikeable jerk. When 'the herd of independent minds' stampedes, there's no stopping them. Llewyn Davis may, himself, be prone to the kind of world-weary cynicism that takes refuge in solitude and self-destructive introspection, but he is also the victim of the more destructive, diffuse cynicism to which the Coens, and most reviewers of their latest film, are in thrall. In his 1991 work, The Cynical Society, Jeffrey Golfarb targets a "knee-jerk," "mocking," or "perpetual" cynicism that decries attempts to live a moral life as naïve. Llewyn is certainly a prickly pear reduced to crash pads on skid row, a little white liar and a disloyal friend, a man whose stubborn pride may predict a fall. But he is also a talented, tolerant, hardy, gentle, patient soul; a compassionate character with considerable integrity; a poet, and a one man band. And we might add that we all have our faults. As Alexander Pope said: "To err is human, to forgive divine." A little more forgiveness, compassion, and integrity wouldn't go amiss. Only last week our editor told me how shaken he'd been by the suicide of a close friend. It took him over a year to get over a shocking blow that, he said, "nearly dragged him under." Such a traumatic emotional upheaval would be enough to turn any sentient soul inward. The tragic suicide of Phil Ochs still hurts me, and I never even met the man.

Llewyn is a wounded animal, benumbed by pain. His taciturn hauteur is matched by the stoic patience with which he tolerates the abuse heaped upon him in Washington Square Park by his button-bright, conformist friend Jean (Cary Mulligan); by his nagging, joyless sister Joy (Jeanine Serralles) at her home in Queens; and by Roland Turner (John Goodman), an obnoxious junky jazz musician on the long drive to Chicago - where Llewyn heads in a determined effort to improve his fortunes. He absorbs their abuse, the cruel blows of fate, and a back ally beating behind the Gaslight Café with equal equanimity. At least Jean's grievances against him may have firm foundations. It is possible he has impregnated her at a time she's keen to bear a child by her partner, his friend Jim (Justin Timberlake). Denied a backstory, aware he's betrayed his friend, audiences will naturally take Jean's (and Jim's) part against him, but there's no suggestion that the procreative act wasn't consensual (as Llewyn reminds Jean, it takes two to tango). Furthermore, although the provenance of the pregnancy is uncertain, Llewyn acts with a certain guilty integrity by fulfilling his promise to secure and finance the abortion Jean wants.

In an interview with the BBC, Joel Coen says: "We do tend to like characters that have a lot of abuse heaped upon them!" It's a disingenuous comment; the Coens, after all, write their own scripts . . . and abuse. Although the Coens almost sadistically stack the deck against Llewlyn, as they do against so many of their characters, they display uncharacteristic tenderness towards him and even allow him a measure of integrity. Perhaps they recognized, better say, created in Llweyn a fellow iconoclast unwilling to compromise his personal vision in exchange for mainstream money. Perhaps they wrote their script with Too Late Blues in mind, for there are obvious parallels between Inside Llewyn Davis and Cassavetes' story of a struggling jazz musician, John 'Ghost' Wakefield (Bobby Darin), who lives a hand-to-mouth existence, is often reduced to couch-hopping, but nevertheless turns down the paying gigs offered by his unscrupulous agent rather than betray his musical principles. Perhaps Cassavetes had heard his contemporary Louis Armstrong say, "Making money ain't nothing exciting to me. You might be able to buy a little better booze . . . but you get sick just like the next cat and when you die you're just as graveyard dead as he is." Is the jingle in your pocket worth the jangle in your mind?

In a keynote exchange Jean and Llewyn clash over coffee in Caffe Regio. Jean asks Llewyn if he ever thinks of the future. He wonders what she means: "What like flying cars, hotels on the moon, Tang? You mean like move to the suburbs, have kids?" She says, "That's bad?" Llewyn defends his view of folk and speaks for the nascent counter-culture when he replies: "If that's what music is to you, a way to get to that place, then yeah. It's a little careerist, a little square, and, frankly, a little sad." It all depends with whom you'd sit, or where you stand. We can but admire Llewyn's fortitude and integrity, and fear for his future. After a fraught drive to Chicago, he arrives – destitute and exhausted, famished and frozen, at the end of the road and his tether – at the Gate of Horn. There, he is invited to audition, on the spot, by agent Albert 'Bud' Grossman (F. Murray Abraham). The Gate's real life Grossman supported black folk-blues greats like Sonny Terry and Odetta. He managed Bob Dylan. The Coens, would you believe it, present him as a cold-eyed cynic. Llewyn naively elects to stake his all on the traditional English ballad 'The Death of Queen Jane'. 'Buddy, Can You Spare a Dime?' might have been a more appropriate and effective choice. Grossman, unsurprisingly, is unmoved ("I don't see a lot of money here"), but then relents slightly and offers him a place in a harmony trio, if he'll only smarten up his act and trim his shaggy beard. No dice. Llewyn's beard is a badge that says he has no interest in teaching the world to sing, in perfect harmony or otherwise, and far less interest in money than those Coca Cola cats. After he turns Grossman down flat, the agent suggests he re-unites with his musical partner. Llewyn's chilling reply is, "That's good advice. Thank you Mr Grossman."

Whatever one's feelings about Llewyn Davis, whether or not the Coens intended Llewyn to be a sympathetic character or not, there is no taking away from the magnificence of Oscar Isaacs' performance. The Coens have said they were delighted and relieved when Isaacs’ ended their interminable search for an actor who could also sing and play guitar. While the Coens listened to Pete Seeger and Bill Big Broozy as kids, Isaacs grew up listening to his father's collection of Bob Dylan and Cat Stevens LPs. Although he honed his musical expertise while playing with punk-ska outfit The Blinking Underdogs, Issacs clearly understands the form his father favoured. He also understands Llewyn's struggles. Speaking in Esquire magazine, Isaacs says: "I think I was a little Llewyn-y when it comes to music as far as managers were concerned . . . there was part of me that wasn't comfortable with monetizing the music . . . so I tended to blow deals a lot." Which is to say, like Llewyn he didn't sell out. His proximity to the character he plays is reflected in an assured performance and some remarkable musical performances. The Coens' foolhardy decision to film 'live' recitals doesn't always pay dividends. It's asking a lot of actors to reproduce the craft and passion of seasoned musicians. Unfortunately, despite Isaacs attuned ear and the sterling efforts of the cast, the folk standards featured in the film all too often fall flat. The cover versions even sound slightly drippy sometimes.

An Aran-sweater-wearing quartet (clearly modelled on The Clancy Brothers), for instance, perform 'The Auld Triangle' as if they were in a suburban church choir. It's a world away from the raw, raucous rasp with which Brendan Behan immortalized the song. Elsewhere in the film, Llewyn sings Ewan McColl's 'The Shoals of Herring' to his incontinent father, and fails to nail it. The real McColl he ain't. Anybody who's heard Ewan McColl, Peggy Seeger, and Charles Parker's ground-breaking work for the BBC's Radio Ballads series will appreciate the gulf separating folk art and bland flim-flammery. And when Jean and Jim join a clean-cut grunt, Troy Nelson (Stark Sands), on stage to sing Hedy West's '500 Miles', it's as if The New Seekers had arrived ahead of time. The cast do their brilliant best with the songs, but their cover versions seldom capture either the provocative bite or melancholic sweetness of the originals.

Such musical shortcomings are typical of the way the film misrepresents the folk scene, which the Coens depoliticise, tidy up, and repackage for public consumption. Theirs is the kind of mocking cynicism described by Jeffrey Goldfarb: the kind that leads to a helpless indifference, which serves the status quo and is the enemy of hope. Without dreams we shrivel; without the belief that cynicism denies them dreams die. Fortunately, the Coens' mocking cynicism is mitigated by inclusive Jewish humour. In one deliciously funny scene, Llewyn dines on moussaka with four folky representatives of the East Coast intelligentsia: the hosts, the Gorfeins (who regularly provide Lleweyn with a bed and board), and another couple (he Jewish, she Chinese) who have decided to merge their surnames and call their son 'Greenfung'.

Inside Llewyn Davis is graced by many such moments of impish wit and the Coens' stifled humanity regularly bursts to life in them. It is ironic, then, that the film's general failure to reproduce folk's intensity of feeling is highlighted in one of its great comic set pieces. If Llewyn symbolizes the folkniks who saw the retrieval and revivification of authentic popular musical traditions as a political act or moral crusade, Jim stands in for the non-committal lightweights who were just along for the ride and didn't quite get it. As loyal as Llewyn is disloyal, Jim supportively offers his friend a fill-in slot at a recording session for Columbia Records. Llewyn leaps at the chance but is bemused by 'Please Mr Kennedy', the schlocky pop single they are to cut. "Who wrote this?" he exclaims. He is aghast and only slightly chastened when Jim innocently admits to authorship. The clever casting of Justin Timberlake as Jim adds an added layer to a perfectly executed in-joke that will work best for those familiar with its context. It's not necessary to know that Mickey Woods original version of 'Please Mr Kennedy' was a flop for Tamla Motown, but it's worth noting that the film's cover version converts a novelty song about the draft into an execrable, if jolly ditty about being sent into space. It's certainly useful to recall that 1961 was the year the tectonic plates of popular culture began to shift: Dylan, fresh from visiting Woody Guthrie in hospital, was cutting his teeth in the Village (he appears in the Gaslight towards the end of the film); the Beatles were starting up in the Jacaranda Club; André Coutand was developing the Éclair NPR (Noiseless Portable Reflex) handheld that was a shot in the arm for independent cinema; and books like Joseph Heller's Catch 22, Harper Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird, and Michel Foucault's Madness and Civilisation were published. It is a shame such harbingers of spring have no place in the film.

Aside from the nods to Dylan in the Gaslight scenes that bookend the film, Inside Llewyn Davis doesn't begin to hint at the seismic social and cultural changes to come. It offers no inkling that the focal point of rebellious energy would shortly shift from Greenwich Village to Berkeley then Haight-Ashbury, or that Vietnam is around the corner. More damagingly, the film offers few clues as to where the folk scene of 1961 came from. There is no sense that Alan Lomax, Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, Jean Ritchie, Hally Wood, Josh White, and scores of others had paved the way for folk's flowering; less sense of the connection between the folk scene and radical politics; and no sense that Greenwich Village had been the epicentre of non-conformist beatnik creativity only a few years earlier. It's hard, while watching Inside Llewyn Davis, to imagine hollow-eyed angleheaded hipsters dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix or burning their money in wastebaskets while listening to the Terror through the walls. Books, drugs, poetry, politics, sex – the Coens are having none of it. After watching Inside Llewyn Davis we could be forgiven for thinking that a group of polite, well-groomed, well-heeled preppie kids must've colonized Greenwich Village simply to share their passion for coffee, cigarettes, and careers in the media. If Llewyn deserved a beating for insulting his assailant's wife, this film demands to be roughed up. And yet, despite it all, the film's period charm and plot-lite pace win us over as easily as the brindled marmalade tabbies Llewyn befriends and misplaces, protects and abandons.

Much has been made of the film's wispy feline subplot. Are these kitty-cats real or imagined incarnations of Llewyn's dead friend? Do they incorporate metaphors relating to Llewyn's vulnerability and the divided self? Might they convey a fiendishly clever allusion to Homer's The Odyssey? Could they contain a cinephile homage to Chris Marker's Guillaume? Are they part of a running gag about the elusiveness of love and tricksy plot devices? The Coens told Rolling Stone that they joked about remaking The Odyssey with hillbilly music and they admitted elsewhere that they dashed off the script for Inside Llewyn Davis with unprecedented haste, so it's probably best to take the cats and the Coens with a pinch of salt and simply say that they flatter to deceive. We can comfortably say, though, that the cats are at the heart of two of the most elegant and affecting scenes in the film. The tracking sequences that present us with a cat's-eye-view of passing subway platforms and walls is matched only by the masterfully executed shots of Llewyn and his cat-companion as they stare in shared bemusement at a downhome beat poet as he mumbles to himself at the wheel. This is luxurious cinematography in which the camera seems to purr. With its understated palette and plot, flashes of folksy wit, and cats, Inside Llewyn Davis may just be the first Coen brothers' film with more soul than sneer.

Peter Seeger sings Waist Deep in the Big Muddy: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uXnJVkEX8O4

Phil Ochs sings When I’m Gone: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Greffl1UVYc

|