|

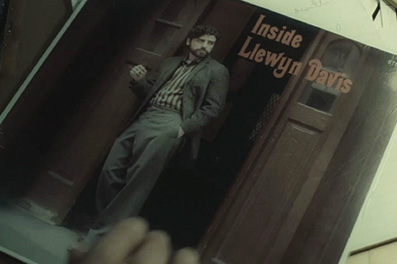

An unlikable protagonist. An unresolved ending. A story about a loser who isn't redeemed. It doesn't take a genius to figure out why the Academy didn't go for Inside Llewyn Davis, which right up until the nominations were announced, was predicted by many to be amongst the Oscar frontrunners. And if the absence of the film's folk revival soundtrack on the gong list feels like an especially egregious kick in the teeth, just consider Oscar Issac's ginger cat co-star, who despite being named Oscar, likely won't be slinking down any red carpets the way The Artist's Jack Russell Uggie did a couple of years ago.

The times are a' changin' for everyone but Llewyn Davis, a man of constant sorrow struggling to find paying gigs and public acceptance in a New York folk scene where he doesn't fit in.

His folk song of woe is as downbeat and desultory as they come, his story the polar opposite of the Coens' other musical O' Brother Where Art Thou, a knockabout comedy set in the Depression era that's about the furthest thing from it. A sun-baked Southern romp that warms the heart, Llewyn's East Coast cold chills to the bone. And yet, of all the films in the brothers' incomparable cannon, O' Brother feels like the most obvious antecedent. Both films feature prominently placed soundtracks curated by T Bone Burnett and both find parallels with Homer's The Odyssey. Most pointedly, the missing cat (played by the aforementioned Oscar) who instigates much of Llewyn's couch-to-couch movement across the city is called Ulysses, his hither and thither wanderings maybe even a furrier, cuddlier metaphor for Llewyn himself.

As if living hand to mouth and losing the cat of the couple periodically putting a roof over his head isn't bad enough, Llewyn's also managed to impregnate the wife (Cary Mulligan) of his best friend (Justin Timberlake), a complication that leaves him with one less place to crash. In a last ditch hope of advancing his career, Llewyn hitches a ride to Chicago to play before renowned club owner and manager Bud Grossman (F. Murray Abraham), but this being a Coen Bros. film, the oddball characters he meets along the way ensure the trip goes anything but smoothly.

In most other films about artists slogging their way to the top, music is a release from their misery, the feeling of performing live a drug of spiritually fortifying power that makes all the pain worthwhile. But music doesn't seem to make Llewyn any happier than he already is, and even his irregular audience at the Gaslight café seem to sense this, as disconnected from him as he is from them. The adage goes that you don't get into the music business to make money, so if not for the joy of performing why is Llewyn up on that stage at all? The film's opening number 'Hang Me, Oh Hang Me' (a cover of Dave Van Ronk, the inspiration for Davis' character and sound) is impressively performed in its entirety by star Oscar Issac and sets a tone of fledgling failure: "It's not the hanging, it's the laying in the grave so long... I've been all around this world."

Self-aggrandizing, prone to confrontation and unduly harsh, if you want to know what's 'inside' Llewyn Davis, as is the case with most musicians, you've got to pay attention to their songs. Even if he wasn't so standoffish offstage and could actually articulate something about himself without offending someone, Llewyn likely wouldn't get a word in edgeways, as every other character in the film is too busy telling us what an enormous asshole he is. Certainly the Coen brothers do nothing to exonerate him or attempt to persuade us otherwise. In one scene Llewyn cruelly heckles a performer, in another he's judging a heavily knitted troubadour before he's even listened to his music, not stopping to think what makes that person a bigger hit with the crowd than he could ever hope to be.

Llewyn's been laying in the grave so long, but that's nobody's fault but his own. Stubborn notions of his obligations as an artist leave him unwilling to compromise the (naive) vision he has of himself in any way, self-destructively slimming his odds of success. When he's offered a job as part of a trio in the folk equivalent of a boy band (led of course by Timberlake's character) he turns it down as a matter of artistic integrity. Purposely short-sighted, he ignores the obvious commercial qualities of a song he plays on (the honky tonk hokum of soundtrack highlight "Please Mr. Kennedy"), demanding to be paid right away rather than wait for the royalties to roll in off the back of a radio hit. Llewyn wants to make it on his terms, but the seismic shifts in the folk scene brought about by the arrival of Bob Dylan (cleverly alluded to at the film's conclusion) mean that such terms are non-negotiable. Or as Bud Grossman more succinctly puts it: "I don't see a lot of money here."

A death-haunted film, Llewyn's inability to pull himself up by his bootstraps has much to do with being marooned as a solo act after Mike, the other half of his folk duo, flings himself off the Washington bridge. He's not good with people or at selling himself and one suspects that any reputation Llewyn had as part of a duo was due in large part to his partner holding down the business end. With no drive to adapt to his circumstances or desire to change them, the closer he gets to Chicago the more obvious it is, that far from being the lost voice of a generation, Llewyn's just a man who's profoundly lost.

The film begins and ends at the Gaslight café, with Llewyn once more playing 'Hang Me, Oh Hang Me', literally and figuratively back where he started. To Chicago and back again lessons have been learned, but ultimately, his talents aren't enough to break the cycle of misfortune. Catching a ride with jerk-off Jazz man, Roland Turner (John Goodman) and his silent chauffer (Garrett Hedlund, On the Road again), the groaning wraith-like sounds of passing traffic woosh round the cinema's surround system in a circular motion, sonically suggesting that Llewyn is on a road to nowhere. The weather is so torrential it's impossible to see outside the car's windows, with only the headlights of other cars cutting through the wintery murk. It's a scene so evocatively lit by Bruno Delbonnel (a surprising but worthy replacement for longtime Coens DP Roger Deakins), it takes on the distinctive netherworld quality of a chiaroscuro purgatory, with Turner the voice of Llewyn's conscience and the artist left having conversations with himself in the backseat.

"And that's what I've got" Llewyn mutters into the mic after his second and final rendition of Hang Me, Oh Hang Me'. It leaves a bleak question mark hanging over his musical prospects. If an indifferent fate has condemned him to lie in the grave a little longer, he's well used to it by now, but if this is in fact the last ever performance of a failed career finally left to hang by the noose, it's probably for the best.

If Llewyn learns anything on his road trip West, it's that all dreams have to die someday.

Inside Llewyn Davis is out now via Studio Canal

|