|

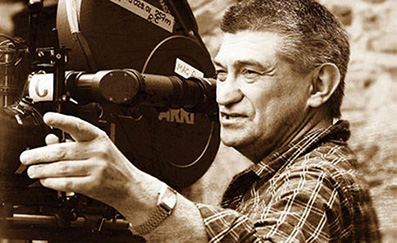

Alexandr Nokolayevich Sokurov long ago established himself among the most important and gifted directors of our moment. So long ago, in fact, that, despite the continuing evidence of his boundless gifts and ceaseless creativity, he has the aura of a figure from an earlier era. That is partly due to the company he has kept. Sokurov's impatience with critics who compare him to Andrei Tarkovsky is understandable, but it's hard not to perceive Sokurov as the natural heir to his late friend and mentor's mantle. They shared a taste for long takes and foggy mysticism. A similarly stark, darkly luminous beauty radiates from the films of both directors, and their investigations into the eternal verities of the human condition are similarly saturated in twilight gloom. When Sokurov tipped his cap to Tarkovsky in Moscow Elegy (1988), though, he finally stepped out from beneath his former teacher's shadow and wrenched free from the influence so evident in his early films featuring Ilya Rivin; from his debut feature, The Lonely Voice of Man (1979), to Empire (1987).

In Moscow Elegy, Sokurov used footage both from Tarkovky's films and from One Day in the Life of Andrei Arsenevich (1999), Chris Marker's own tribute to the late giant of late Soviet cinema. Given Sokurov's consistent engagement with the past, his ongoing interest in Japan, his predilection for the essay-film form, and the preponderance of documentaries in his oeuvre, it now seems more fruitful to compare him to Marker rather than Tarkovsky. It is a shame that Sokurov's Eurocentric woldview is far removed from Marker's internationalism.

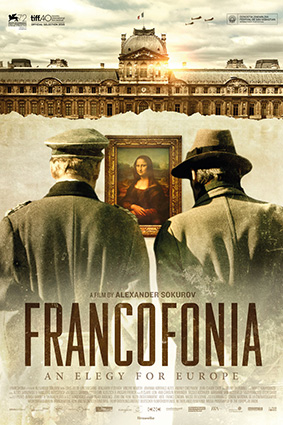

In his multi-layered, mixed-media documentary Francofonia, Sokurov returns to the Markerian subject of tyranny he explored in his tetralogy on men of power: Moloch (1999), Taurus (2001), The Sun (2004) and Faust (2011). As he did in his renowned one-shot-wonder Russian Ark (2002), he invites us to join him at the museum and then guides us through its contents and history with the help of various mythical and historical characters. In this instance, the museum is the Louvre not the Hermitage in St Petersburg but that city and its famous museum appear in Francofonia too, when Sokurov returns to another recurrent theme in his work: Soviet sacrifice and suffering, especially at the battle of Leningrad.

Francofonia is an engrossing, enriching meditation on the importance and fragility of art and museums, the ravages of war, the European project, and the fraught relationship of Russia to the rest of the continent. This complex but overwhelmingly coherent film is built from the bricolage of grainy archive footage, sepia-tinted historic re-enactment, filmed paintings and painterly filming. Sukarov grounds his discursive visual essay in the initially uneasy, ultimately warm wartime relationship between a German aristocrat, Count Franziskus Wolff-Metternich (Benjamin Utzerath), and a French Republican, the Director of National Museums, Jacques Jaujard (Louis-Do de Lencquesaing). Their ideological differences belied their shared belief in the centrality of art to civilisation and the two nominal enemies forged an alliance of convenience in their battle to safeguard the museum's collection.

Jaujard, with the able assistance of Rose Valland (played by newly appointed BFI Fellow Cate Blachett in Monuments Men) had already transferred thousands of artworks to chateaux across France in anticipation of the Nazis' conquest of Paris. So, when the Nazis eventually seized the Louvre all that remained were a scattering of immobile statues. Rearguard action was still necessary, though, to protect the dispersed collection from an acquisitive German high command. The relationship between Jaujard and Wolff-Metternich is integral to Sokurov's case for a wider vision of European unity than currently exists. Europe, he argues, must rally behind its common cultural heritage. It is odd, then, that he opens his case for Russia's inclusion in a new Europe with scenes involving Chekov and Tolstoy. It is odd, too, that he makes no mention of the fate of Europe's vital store of cinematic treasures.

Sokurov's reverence for European fine art and respect for Soviet wartime heroism is matched only by the intensity of his Francophilia. The film opens with a paean to French film-making and ends with a stunning recreation of the tricolour. At one point Sokurov calls Paris "the centre of world culture." Later, he asks, "What is left of France without its Louvre?" "Her cinema, surely, and her literary, philosophical and political traditions" we might reply, on his behalf. Throughout the film, Marianne (Johanna Korthals Altes), emblematic heroine of the French revolution, repeatedly murmurs the Republican battle cry 'Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité' to herself while Napoléon Bonaparte (Vincent Nemeth) essentially mutters 'To the victor go the spoils'. Art means little to dazed, embattled Marianne. For the pompous pint-sized Emperor ("that imperial impersonation of force and murder known as Napoleon the Great"), the Louvre is himself incarnate ("C'est moi! C'est moi!"), an extension of his unhinged ego. Vainglorious conquerors ludicrously seize art to establish national superiority and their own immortality, but art prevails, doggedly transmitting its vital messages to the future from the past, reminding us, finally, of our common fate.

Meanwhile, as those four historical figures come and go, playing out the metaphors of European unity, revolution and reaction, the captain of a container ship bearing art treasures through storm-tossed seas intermittently communicates with Sokurov by Skype. When the signal is sufficiently strong, Dr. Dirk is able to convey his increasingly urgent dilemma: should he jettison a part of his cargo to save his skin or risk the loss of his vessel and death by drowning? The freight of meaning is clear and the question recurs throughout the film: is art worth loss of life or must we preserve and honour it, at all cost, as the civilising embodiment of humanity itself? Elsewhere in the film, Sokurov wonders why portraiture has been so uniquely central to European art and sees the people in the Louvre's many thousand faces. Must we regard representations of ourselves in order to be persuaded of our existence?

Curiously, Francofonia sits among a cluster of recent documentaries about museums. With cinemas now broadcasting live opera and theatre performances, we should not, I suppose, be too surprised that museums have followed them into cinemas. The binding subplot of Francofonia mirrors the story told by Jean-Pierre Devillers and Pierre Pochart's TV documentary Illustre et inconnu: comment Jacques Jaujard a sauvé le Louvre/The Man Who Saved the Louvre (2015). Although Sokurov's film shares broader similarities with both National Gallery (2014), Frederick Wiseman's film on London's National Portrait Gallery, and Das Grosse Museum (2014), Johannes Holzhausen's film on Vienna's Kunsthistorisches Museum, it bears an particularly striking resemblance to Jem Cohen's Museum Hours (2012), which also focuses on the Kunsthistorisches.

Luc Sante says of Cohen's exquisite collagist: "Museum Hours suggests Cohen's descent from Jean Vigo and Chris Marker, two poetic film-makers who were fully engaged with the world and knew how to balance thought and feeling . . . While it is possible to say what it is about, it is much more difficult to say what it is. In its modest yet unassuming way it is a total experience, composed of people, sights, sounds, history, travel, argument, speculation, fantastic beauty and ordinary life, woven together and maintained in aerodynamic tensions. It is no more reducible than a day in Spring." Much the same could be said of Francofonia. "Modest" and "unassuming," though, it is not. At times it feels like a longer version of Museum Hours made with a budget a hundred times or so larger.

Cohen and Sokurov brilliantly make the most of their respective resources but while necessity is the mother of invention for the American, the Russian master is able to express his own tendency toward experiment on a more spectacular scale. In one of the many astonishing images that grace Francofonia, a Luftwaffe bomber glides unnaturally past a window in a courtyard of the Louvre. At another point in the film, a flight of Heinkels drone menacingly over an eerily pastel Paris, exactly as they do over Stockholm in the memorable closing sequence of Roy Andersson's You, the Living (2007). Sokurov's deft use of colour, like Andersson's, creates an atmosphere by turns dreamlike and nightmarish.

At times, Sokurov's justifiable pride in his technical virtuosity leads him to overplay his hand. Many will have felt he did so in Russian Ark. He has a tendency to hold a carefully composed shot a fraction too long, as when a human hand reaches out to a sculpted marble one for a minute or two in Francofonia. More generally, his consummate control of the camera complements his predisposition toward the instructive and pedagogical. Despite occasional self-indulgent lapses, his spiralling arguments are generally in perfect harmony with the scintillating beauty of his camerawork. Sokurov says he doesn't much like cinema and talks more often of Russia's literary giants than her cinematic greats, but he crafts images every bit as splendent as those sculpted by his cinephile contemporary Andrey Zvyagintsev.

Sokurov's cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel (whose previous credits include Amélie (2001) and Inside Llewyn Davis (2013) deserves enormous praise for the ravishing look of the film. So, too, do Sokurov's large visual effects team. A 360-degree pan across the rooftops of Paris and a shot over a ship's prow into the heaving ocean, for example, take the breath away. Equally impressive is the way Delbonnel's camera - in tandem with judicious use of diagetic sound effects (creaking floorboards, chirruping birds, barking dogs) - bring the paintings to life through focus and fade, zoom and dissolve. The archive footage, too, is brilliantly effective in recapturing the mood of occupied Paris and of blockaded Leningrad, where corpses lay unburied in the street because the citizenry lacked the strength to bury them. Sokurov delights in defying formal convention. In place of the usual opening credit sequence, he deploys a split screen that rolls names to left and plays conversations between himself and various colleagues to right, while the traditional closing credits are replaced with a blank screen over which an orchestral coda plays.

Francofonia is subtitled 'Elegy for Europe' but might just as easily be subtitled 'Elegy for Russian'. In his finely modulated narration, Sokurov says: "The goals of states and of art seldom collide." Like Tarkovsky before him, he was banned by Soviet censors; like Marker before him, he has been a consistent thorn in the side of power. Above and beyond the aesthetic affinities and shared sensibilities that bind him to those directors, though, are those he shares with the great Russian rebel and folk hero, Vladimir Vysotsky. Like Vysotsky, he is a privileged cultural symbol protected by his international standing whose outspokenness endears him to ordinary Russians. Both absorbed admiration for the military virtues from fathers in the military. As Vysotsky did, Sokurov balances anti-authoritarian, anti-Soviet revolt with respect for Russia's literary heritage and national wartime mythology.

In Francofonia, Sokurov's criticisms of the powerful are veiled but telling. For Napoléon Bonaparte read Vladimir Putin. The Russian leader may have bankrolled Sokurov's Faust but he cannot have hoped to receive anything in exchange, other than a fine film and enhanced national prestige. Although Sokurov was happy to receive that assistance his contempt for the kleptocratic tribute system that underpins Putin's corrupt and corrupting regime is writ large in all he says (the vast sums paid in bribes by Russian businesses rose from $34 billion to $318 billion between 2001 and 2005 alone; nearly a sixth of GDP). "What is the state there for unless it is to help us in the social sphere and the sphere of culture?" Sorkurov asks. He also he notes, slyly, "There is an irony when a man who has so much power helps you complete your work on men in power."

No admirer of revanchist Russian capitalism or friend to his country's oligarchs and plutocrats, Sokurov more generally speaks out through his films, as Vysotsky spoke out in his songs. A delicious, Soviet-style joke doing the rounds points out that Putinesque terms like 'sovereign democracy' and 'managed democracy' are to 'actually existing democracy' what 'electric' is to 'chair'. Putin's authoritarianism is summed up in a chilling new Russian word: Bezalternativnost – 'alternativelessness'. In such dispiriting circumstances, Russia needs directors like Sokurov and Zvyagintsev more than they need Russia. "Cinema is not a luxury," Sokurov has said, "It is the basis of the development of society." It is regrettable, then, that Sokurov elected to present the case for preserving great art without mention of the equal claim to our attention of the ongoing crime of the destabilization and destruction of moving images. This omission is especially galling given that Francofonia draws much of its force from the raw materiality of preserved and restored archive footage.

|