"There is a new face in Irish cinema. The make-up is finally coming off.

The conventional and generic Irish films of the past are being replaced

by what could be referred to as 'The Irish New Wave' . . . We have for

too long focused on perfecting the script when in fact some of the finest

work in this country . . . came about through a uniquely personal way of

working. These films show that the logic of film can work in a very

different way than a rigidly plotted out story on paper." |

From Mark O'Connor's manifesto, Irish Cinema: A Call To Arms, 2012 |

In an interview for the Winter 2012 edition of Filmmaker magazine, Dublin-born director Kirsten Sheridan acknowledges the importance of Ireland's literary and storytelling traditions and suggests that filmmaking is still widely regarded as a foreign trade in the Republic. She says: "We're not really a visual culture . . . Irish film has emulated other countries." The tragic news of Seamus Heaney's death last week provided both a reminder of the might of the Irish literary tradition and circumstantial evidence supporting Sheridan's claim. In a moving Guardian obituary, writer Colm Tóbín says of the late Nobel laureate: "He was not merely a central figure in the literary life of Ireland, but in its emotional life, in its dream life, in its real life." On the same page of the same newspaper, poet Paul Muldoon went even further to emphasize Heaney's importance within Irish culture: "He managed, in ways that are more or less unheard of, to be a poet and a public figure . . . people looked to him almost as one might to the Delphic Oracle." No Irish filmmaker, no matter how revered and renowned, could hope to occupy such an exalted position. The mere idea of cinema producing a figure of such stature would seem foreign to the Irish.

Irish cinema has, historically, played second fiddle to Irish literature and theatre. It is as if the weight of Ireland's literary and theatrical traditions crushed the life out of her cinema, as if her great novelists, playwrights and poets intimidated her aspirant filmmakers to the point where they faltered, lost the courage of their cinematic convictions, and fled the field. We can but wonder what might have been had Beckett's application to study under Eisenstein had been successful, or if Joyce, having established Dublin's first cinema in 1909, had set his sights on filmmaking. We can say with certainty, however, that for as long as Ireland lacked a thriving film industry she tended to be viewed through the distorting lens of the outsider. From Alfred Hitchcock's adaptation of O'Casey's Juno and the Paycock (1930) through to Joseph Strick's adaptations of Joyce's Ulysses (1967) and Portrait of a Young Artist (1977), Irish letters and the Irish stage provided source material primarily for non-Irish directors. This wasn't merely a matter of the reach of UK and US studios. De Valera's enforcement of conservative values may have done as much to nip Irish cinema in the bud as the weight of contending traditions. The Censorship of Films Act of 1923, in particular, militated against experiment, discouraged potential filmmakers, and curtailed resistance to Anglo-Saxon misrepresentations of Ireland and Irishness.

The likes of Flaherty, Ford, Launder, Lean and Sirk may have offered less odious stereotypes of the Irish than those present in the top-o-the-mornin' paddywhackery of Norman Taurog's Little Nellie Kelly (1940) and Robert Stevenson's Darby O'Gill and the Little People (1959), but cinematic views of Ireland were overwhelmingly shaped by non-Irish directors until the scene-changing arrival of Neil Jordan and Jim Sheridan in the 80s. Jordan and Sheridan didn't safeguard the Irish from identity theft, and romantic myths of a prelapsarian, pre-modern Ireland persist in films like Waking Ned (1998) and Leap Year (2010), but they edged Irish cinema toward the modern and metropolitan while pinning it firmly on the international map. It is unsurprising that those two directors were, for a while, synonymous with Irish cinema: cinema has, after all, been equally synonymous with technological innovation so a vibrant national cinema only emerged after Ireland had made the painful transition from an agricultural to industrial economy.

The relatively recent revolution in the Irish film industry was a long time coming and long overdue. It was not until 1993, when the Irish Film Board (founded in 1980, disbanded in 1987) was re-established, that Irish cinema burst into life. Under the dynamic leadership of Leila Doolan, the IFB transformed the Irish film industry thereafter. After 1993, the whispers among cinephiles gradually grew more excited, the trickle of Irish films at festivals turned into a steady stream, and films were soon pouring forth from Ireland as never before. Irish theatre had always provided acting and writing talent galore, now the Irish began getting behind the camera in numbers. Long before Tomm Moor and Nora Twomey at the Cartoon Salon made the Republic's first animated feature, The Secret of Kells (2009), it was that clear that Irish cinema had, at last, come of age.

Of course, Irish cinema didn't arrive in 1993: silent film pioneers John McDonagh and Fred O'Donovan had pointed to the future; national broadcaster RTÉ, which began transmitting in 1961, had helped it on its way; and, from the mid-70s on, 'First Wave' directors like Cathal Black, Joe Comerford, Kieran Hickey, Pat Murphy and Bob Quinn were busy preparing the ground for the renaissance to follow. The introduction, in 1997, of the Section 481 tax incentive scheme for film added another significant building block. Since 1993, Doolan's successors at the IFB (notably Simon Perry, who developed vital European co-production contacts) have presided over a sixfold increase in the number of people working in the industry and an exponential rise in the number of Irish films. A government expenditure review of 2008 made the case for continuing public support of the IFB with some staggering statistics: the average annual value of audiovisual production shot up from €14m between 1982 and 1992, to €151m between 1993 and 2003 – a tenfold increase.

At this point a necessary note of caution must be sounded. In his book The Myth of an Irish Cinema: Approaching Irish-themed Films (2006), Michael Patrick Gillespie quotes a different set of statistics that testify to the continuing grip Hollywood has on Irish cinemas and the Irish imagination. He says: "Recent figures from the liscencing board show that the vast majority of films approved for screening in the Irish Republic are American . . . From 1997 to 2005, 1,755 films were submitted for liscencing . . . Only 6 per cent were Irish films . . . Hollywood-style films appeal to the Irish, and no Irish filmmaker can hope to succeed financially by ignoring that attitude." Supporting evidence for that bleak, if defeatist prognosis was recently provided by Screen Digest (now owned by Colorado-based industry analysts IHS), whose number-crunching pencil necks report that Irish ticket sales dropped from 18.2m in 2008 to 15.4m in 2012, while box-office takings fell from €131m in 2009 to €108m in 2012. If your first thought on reading those figures was that the fall in ticket sales and box-office revenue must reflect an awakening on the part of Irish audiences, if you assumed that a section of the Irish cinema-going public must have grown bored of blockbusters, disgruntled that their country and culture wasn't more accurately represented on screen, and voted with their feet, think again: such figures, obviously, have more to say about rising ticket prices and recessionary times. Skyfall raked in €6m in Ireland last year, while the box-office hit of the year so far has been Iron Man 3.

Such statistics make depressing reading for those loyal to the idea of a cinema that reflects local realities and entertains in less spectacular ways. 'Youngish Irish filmmaker seeks mature Irish audience. I am idealistic, lonely, loving, passionate, perhaps slightly impractical. Seeking same for long-term relationship based on mutual trust'. The dominance of Hollywood in Ireland, as elsewhere, should strengthen the cases for continuing or increased public subsidy for the Irish film industry, for a (more progressive) form of the cultural protectionism practised in the de Valera era, and, at mininum, for subsidised cinema tickets and a French-style tax on foreign films. The leaps-and-bounds progress already made by the Irish film industry shows how far political will and public money can push Irish cinema. Academics, critics, film journalists and reviewers, myself included, have struggled to keep pace with the growing number of Irish films made since 1993 – not least because some of the best have appeared only on Irish TV, in Irish cinemas, at remote festivals. In his compendious reference guide The Irish Filmography: 1896-1996, Irish film historian Kevin Rockett, having sketched the criteria for inclusion in his list ("fiction films made in Ireland and about Ireland and for the Irish'), lists two thousand 'Irish' films, only a couple of hundred of which were made by Irish filmmakers. Any update of his book will significantly amend that ratio in favour of indigneous production.

The changes of the last two decades are writ large in Mark O'Connor's bold, brash manifesto, Irish Cinema: A Call to Arms *, which he launched at the Galway Film Fleadh last year. In his manifesto, he delivers an impressive roll call of Irish cinematic talent: Colin Downey, Lance Daly, Ciaran Foy, Ivan Kavanagh, Terry McMahon, Brendan Muldowney, Ian Power, Ken Wardrop, Carmel Winters, Juanita Wilson, and himself. His own spikey, micro-budget features are typical of the way these filmmakers have transformed necessity into invention. O'Connor deserves credit for his audacity and courage: it took guts to break ranks by delivering this provocative statement; it took balls to name his third film Stalker. I hope his "call to arms" is heard and that he's right to suggest these directors are driving the "emergence of a new kind of cinema," but, as one would expect given his laudable polemical intentions, he overstates his case when he talks of an 'Irish New Wave'.

As O'Connor's choice of quaintly familiar, if charged terms suggests, the directors he mentions represent not so much rupture as continuity. They face common challenges in representing changed socio-economic circumstances, but are responding to the implosion of the Irish 'economic miracle' in very different ways. They aren't yet bound to any unifying set of aesthetic principles, don't yet share any particular political position, haven't coelesced around any given film journal, and most certainly aren't reacting against any cinéma de papa. The key word there is 'yet'; there is always the possibility that there might be a coming together of a significant group of Irish directors around a unifying set of practices or political perspectives. As things stand though, it might be more productive, to locate those O'Connor lists within a 'Second Wave' continuum (beginning with the Second Irish Film Board) and group them with a wider range of directors (of various ages, some emerging, others already established). We might then usefully talk, too, of a 'New Irish Cinema' or ongoing 'Irish Film Rennaissance'. That those terms carry echoes of the Australian New Wave calls attention to the obvious similarities between the cinemas of Australia and Ireland: down under, the great year of change was 1976; in Ireland, it was 1993; in both cases a national film culture was stimulated by a benevolent state with progressive views on the cultural and economic importance of film.

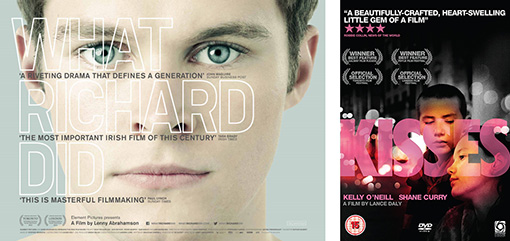

If we cannot yet make out a fully formed 'Irish New Wave', we can confidently say that the absence of aesthetic and political unity in contemporary Irish cinema highlights the presence of a healthy diversity characteristic of a mature, vital national film culture. A group of directors, although not (yet) united behind any defining principle and not (yet) in any way a 'New Wave', are offering a collective resistance to Hollywood hegemony and global homogenisation, a collective defence of a national cinema that acknowledges the plurality of contemporary Irish identity. A snapshot of a small sample group of Irish directors and their recent films immediately illlustrates that diversity. Over the past decade alone 'new' Irish directors have given us horror films [Ivan Kavanagh: Tin Can Man (2007), Ciaran Foy: Citadel (2012)] and poetic documentaries [Ken Wardrop: His and Hers (2009), Pat Collins: Silence (2012)]; films set in middle-class milieux [Liz Gill: Goldfish Memory (2003), Lenny Abrahamon: What Richard Did (2013)] and 'on the streets' [Lance Daly: Kisses (2008), Mark O'Connor: Between the Canals (2011)]; films about boxing [Mark Mahon: Strength and Honour (2007), Ian Palmer: Knuckle (2011)] and dysfunctional families [Margaret Corkery: Eamon (2009), Carmel Winters: Snap (2010)]; about musicians [John Carney: Once (2007), Lisa Barros D'Sa & Glenn Leyburn: Good Vibrations (2013)] and the Traveller community [Perry Ogden: Pavee Lackeen (2005), Mark O'Connor: King of the Travellers (2011)]; about rural Ireland [Gerard Hurley: The Pier (2012), Gerard Barrett: Pilgrim Hill (2013)] and recent Irish history [Des Bell: The Enigma of Frank Ryan (2012) Leila Doolan: Bernadette: Notes on a Political Journey (2012)]. This limited snapshot alone hints at the wide range of (interconnected) thematic concerns and continuity of production you'd expect to find in any thriving film industry.

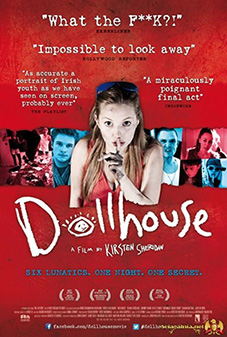

Kirsten Sheridan makes for an illuminating case study that further emphasises that diversity. She is law unto herself, as we shall see, but she has much in common with Mark O'Connor and his figurative cohorts. Two of her three features sit beneath that umbrella category of recent films that focus on working-class life and, inevitably, tend to feature crime, drugs, sex and violence. Sheridan is an interesting woman and director, but she is worth considering for reasons other than her likeable personality and films. She is an important figure in Irish cinema. A benificiary of Irish Film Board funding and distribution assistance (Dollhouse was kick-started with a €15,000 IFB development loan), Sherdian has herself sat on the IFB's rotating Board. She is part of the Irish filmmaking family that includes her renowned father, Jim – director of films such as My Left Foot (1989), In the Name of the Father (1993), Get Rich or Die Trying (2005), and the notoriously troubled Dream House (2011); her sister Naomi – who shared a co-screenwriting credit and screenplay Oscar nomination with Kirsten and her father for In America (2002); and her uncle, Peter Sheridan – director of Borstal Boy (2000).

Sheridan is her own woman though, with her own drives and gifts. Significantly, she co-founded filmmakers' collective the Factory, the 'creative hub' used by filmmakers like Mark O'Connor and praised in his call-to-arms manifesto. There's an exquisite poetic justice about the Factory story. It benefited from the economic crisis, which made it possible for it to occupy a derlict Dublin warehouse on favourable terms, and it is now well-placed to offer a cinematic response to that crisis. In an interview for Variety, Sheridan says: "Films like Once and Kisses are rough around the edges, but with a lot of heart in them . . . Rather than doing the Dogma thing and setting rules, we decided that the way to find a national identity is through that openness . . . The more you focus on what makes it personal, then the more it feels something like a Wave." The Factory's production facilities and actors' studio were a significant factor in shaping Dollhouse and the film is entirely in keeping with O'Connor's ethos of intense, collaborative work with actors. Dollhouse, then, seems as good a place to test O'Connor's claims as any.

Sheridan's precocious feature debut, Disco Pigs (2001), hinged on two unhinged teenagers, Darren ('Pig') and Sinead ('Runt') – next-door-neighbours and soulmates born at the same time, in the same hospital in Cork ('Pork'). That raw, raucous film charted the adrenalin-and-alcohol-fuelled violence surrounding the disintigration of an unusually intense relationship that ends in tears. Sheridan's next project was her above-mentioned writing collaboration with her sister and father on In America (2002) – an earthy, happy-ever-after tale of an Irish family's struggles to establish themselves in the Manhattan. Having established herself in the States, Sheridan remained there to make her second feature, August Rush (2007) – a large spoonful of Hollywood sugar with a sickly happy ending. That drippy, droopy film told the tall tale of an adolescent orphan whose preternatural gift for music ultimately unites him with his long lost parents, at a Central Park concert performance of his own self-penned rhapsody. Sheridan's compelling third feature, Dollhouse, marks a return to familiar (culty, low-budget) ground. It is a brassy, messy chamber piece in which five wired-up Dublin teenagers break into a flash Dalkey dreamhouse for a night of drink-and-drug-fuelled debauchery and destructiveness.

Dollhouse, the opening credits announce, is – surprise, surprise – a product of the Factory, which Sheridan established in 2010 with John Carney and Lance Daly (who are credited as executive producers on the film, along with Jim Sheridan). Sheridan helped establish the Factory while trying to get big-budget film projects off the ground, but eventually switched tack, and decided to shape a film out of thin air there – without a script, working solely from a sketchy 15-page treatment, the gist of which was drip-fed to the cast. So, Sheridan, her small crew, and a tight team of six core actors, built the film on set and through workshops at the Factory; manufacturing plot twists, dialogue, and scenes during a continuous 21-day shoot. This is the admirable improvisational aesthetic championed by Mark O'Connor in his manifesto and favoured by New Waves the world over. It works wonders . . . when it works. In Dollhouse, this DIY, make-do-and-mend methodology generates gripping moments of surprise and suspense, but, sadly, leaves a gaping hole where characterisation, coherence, credibility and ideas should be.

As the film begins, the five teenagers – Eanna (Johnny Ward), Darren (Ciaran McCabe), Denise (Kate Stanley Brennan), Jeannie (Seána Kerslake) and Shane (Shane Curry) – bunch exitedly at the front door of the modernist palace, considering smashing their way in. Denise, the guiding intelligence of the group, put the breaks on violence (as she will throughout the film): "Cool, cool," she says, "Jeannie's been watching the gaff." Once inside the building, the group are stunned by the luxury they encounter – all except Jeannie, who seems more at ease in such surroundings than her companions and peels off from the pack to explore the house as the others raid the drinks cabinet and medicine cupboard. No sooner have they begun to relax and rev up than the increasingly merry band is further stunned to learn, courtesy of a box of photographs they find, that they have careered into Jeannie's family home. 'What the f**k?!' This reviewer was no less stunned to learn that the house in question, the film's sole location, is 'Martha's Vineyard' – a multi-million euro property in Dalkey (seaboard playground of the rich and famous) owned by Sheridan's parents, who, fortuitously, happened to be in the States (filming Dream House) when Dollhouse was being conceived. 'What the f**k?!' indeed.

In an online interview with Movies.ie, Sheridan says: "I knew (my parents) were going to be gone for a few months, so I just said to John Carney: 'We should make a film, we have a free house', and he said, 'No, it's your house. You should make the film'. Then I got an idea of the clash of two worlds. I couldn't really write about the people who live in Dalkey because it's not really my world, so I thought I'd bring the kids (from the Factory) I do know out there." Sheridan's disarming claim about which worlds and people she does and doesn't know strikes me as, let's be generous, disingenuous. The house came first, the film followed; which is to say, let's be frank, Dollhouse wouldn't have happened if Sheridan weren't closer to Daddy and Dalkey than to the 'kids' of inner-city Dublin. Dollhouse is a product of priviledge. Most films are: budgets and cameras all too rarely fall into working-class hands. In the scenes where the characters film one another with expropriated 'mini-cams' they are representing themselves to themselves in a way we seldom see on screen. In a film in which class conflict simmers just beneath the surface, such scenes and the film's location add additional layers to the questions it raises (but fails to answer) about material advantage and the possession of cultural capital.

The unspoken class tensions that first surface when the group discover that Jeannie is not what she had seemed resurface when the middle-class boy-next-door, Rory (Jack Reynor) arrives to see what all the noise is about. The group's subliminal class-consciousness kicks in again and their persecution of Jeannie only abates when they insinctively round on Robbie. This material, like the film's location, presented Sheridan with a golden chance to explore the question of class and address the social iniquities of modern Ireland, but she spurned it. When we view the image of Seána Kerslake with her forefinger to her lips in the film's promotional poster, we can imagine her saying: "Shh. Don't mention class!" Perhaps Sherdian's own position in that "clash of two worlds" became obvious to her as the project developed, causing her to baulk at the questions it raises. Be that as it may, not one conversation takes place in Dollhouse about the disparities in the social circumstances of the six main characters.

The scene, early in the film, when Darren dances to Grieg's 'In the Hall of the Mountain King' as if he's in a club recalls Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange (1971), while the break-in scenario also calls to mind Hans Weingartner's The Edukators (2004) and Michael Haneke's Funny Games (2007). Sheridan's film is purposeless in comparison: it has nothing (intentional) to say about class, hedonism, inequality, violence, society or politics. As we might expect given the circumstances of the film's conception, Sherdian runs scared from the retributive justice dished out in Weingarten's film and hinted at in Haneke's. Because she presents no context whatsoever for the characters' actions, Dollhouse falls into the depressingly large category of films that fabricate the fear that a feral underclass is howling threateningly at the gates of happiness; dangerous, disturbed, capable only of animal hedonism and mindless violence; requiring restraint, persecution, prosecution and punishment.

In the absence of any explanatory or guiding context, the unanchored characters are cast adrift to bob on that vast ocean of prejudice unaided while the directionless narrative, lacking any moral compass, ultimately sinks beneath a tidal wave of vingettes. Sheridan had a free hand and worked without outside interference, so the decision to deny the characters either backstory or voice was hers alone. The only stipulations Sheridan's parents made before handing over the keys were that nobody must die in the film and that any mess made be cleared up afterwards, children. It doesn't give much away to reveal that nobody does die in the film. As to mess, in one brilliantly conceived scene Jeannie's bedroom is inventively turned upside down, but we can safely assume the furniture in that room was nailed to a studio ceiling not one Chez Sheridan. That scene aside, a few props are wrecked (a chair, a sofa, a table top), but otherwise no damage is done to the dreamhouse that couldn't be rectified with a tub of turpentine, a pot of paint, and a dustpan & brush. The cinematic mess Sheridan makes is another matter entirely and the damage done to her reputation will take longer to repair.

The performances of actors can make or break improvised, unscripted film such as this, so it is more important than usual to weigh up the actors strengths and weaknesses. The first thing to say is that the cast cannot be held to responsible for failings flowing from flimsy direction. Sheridan has a penchant for implausible dramatic endings and she must carry the can for the one she dreamed up for Dollhouse, a clumsy finale that stretches credulity beyond breaking point, destroys the film's credibility at a stroke, and ruins much of the good work of her actors. Sheridan must also be taken to task for her equally heavy-handed and damanging decision to use a hammer in the film as a recurrent trigger of tension. Her crassly manipulative misuse of that useful tool, and her subliminal insinuation that it might be used as a weapon, suggests a lack of faith in her audiences and her actors.

To make matters worse, Sheridan fails to tackle the inevitable minor blemishes in the performances of the young core cast. Particularly in the opening scenes, the actors rely too heavily on their hoods and a tiresome number of feckin "fucks" to deliver a sense of scallie authenticity, and, throughout the film, their mumbled lines and overstressed accents are often inaudible. Johnny Ward and Ciaran McCabe occasionally overplay their parts and too readily ape stereotypes of slack-jawed working-class masculinity, while Seána Kerslake slightly underplays Jeannie, who often comes across as an insentient doe-eyed 'doll'. Such flaws in otherwise excellent performances would have been apparent to a more discerning director and could easily have been addressed by Sheridan either during the shoot or editing process. The film's loose-limbed methology would have worked better with assured direction and the cast would have benefited from more guidance.

Despite, even partly because of the reservations expressed above, Dollhouse makes for riveting viewing. Because Sheridan doesn't allow us to really know the characters she and her cast create, we are left to play the fascinating game of guessing which gestures and actions belong to and spring from the individual actors, as people, and which to the characters they play. The lack of social context may leave the characters unformed and unfathomable, but it coincidentally intensifies the claustrophobic tensions caused by the film's location. Almost entirely improvised though it is, Dollhouse also benefits from high production values. Sheridan boldly and brilliantly edited the film herself, presumably in the editing suite at the Factory. She skillfully paces the film so that the threat of violence repeatedly rushes at us then recedes and she shrewdly maintains a (comparatively) restrained approach to music. Colin Downey and Ross McDonnell's edgy cinematography underscores the film's sense of menace and momentum, and their work is enhanced by clever use of camcorders. The performances of the film's core cast (four experienced hands and two rookie actors), though, are its crowning glory. They contribute most that is good about Dollhouse and deserve great credit for their individual inventions.

Kate Stanley Brennan, Shane Curry, and Jack Reynor (who subsequently played the lead in Lenny Abrahamson's What Richard Did) seldom put a foot wrong. Stanley Brennan, who comes from a well-know Irish acting family, brings great understanding to the moments in which Denise diffuses male violence, repulses Eanna's advances, and offers streetwise, sisterly support to Jeannie ('You don't fool me baby girl"). Reynor demonstrates his range by combining vulnerability and self-possession, gentleness and ferocity. The superb Shane Curry, though, steals the show. Poised, photogenic, possessed of a quietly compelling screen presence, he has clearly come on in leaps and bounds since his boyhood debut in Lance Daly's Kisses. Shane's watchful intensity, quiet flashes of anger, and understated intelligence catch the eye throughout.

In a film driven by well-executed scenes and enthusiastic performances, it is the less spectacular ones that stand out in the memory. The scene, for example, in which Shane and Jeannie resolve their differences during a bathroom tête-à-tête is played with great delicacy by Curry and Kerslake. The actors generally improvised their own dialogue, so it's also worth mentioning the scene in which Eanne goes for Darren's throat during a game of spin the bottle. This is not random violence. Eanne's kid brother has been battered and someone fitting Darren's description has been sited during the attack. That scene is also worth mentioning because it is the only one in which we are offered any background information about any of the characters. The cast can take a bow and Sheridan has every right to join them: she had made an eminently watchable film that makes most of its limited resources, even if it is short on ideas and full of holes.

Where does Dollhouse leave Mark O'Connor's manifesto and his claims for an "Irish New Wave'? In the middle of nowhere! It provides both encouragement and cautionary lessons for anyone inclined to respond to his 'call-to-arms'. On the one hand Dollhouse demonstrates what a decent director with a dedicated cast can achieve without much money and without a script, on the other hand it reminds us that collaboration and a committed cast do not, in themselves, to guarantee great cinema. On the one hand Sheridan proves that an "Irish New Wave" is possible (even if she is unlikely to be within its ranks), on the other hand she is as far from the cinema of "protest" O'Connor calls for as it's possible to be without putting actors in pretty costumes and retreating into the 19th Century or rushing, cap in hand, to Hollywood. Sheridan demonstrates that a willingness to take risks can pay dividends while simultaneously reminding us that a fear of uncomfortable, unfashionable or unpalatable ideas can stymie experiment as surely as supine surrender to Hollywood models of filmmaking. Public intellectual Jacqueline Rose has said that, without her really aware of it, Rosa Luxembourg taught the point is to "force the unthinkable (in all its guises) into the language of politics." Sheridan seems unlikely to learn such a lesson, but any 'New Wave' worth the name must be unafraid of doing so, or, at minimum, be prepared to think of the possibility of doing so, as Mark O'Connor has.

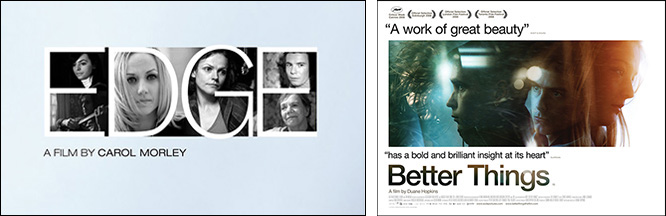

Sheridan's comments, in Variety, on the importance of personal vision to the formation of any 'Wave' (be that 'Second' or 'New') imply that she has thought beyond herself at least to the extent of wondering where she might fit in to any 'Wave'. Similarly, her comment in Filmmaker that "Irish film has emulated other countries" implies that she has thought about that issue as a problem. Dollhouse raises the question of what an 'Irish New Wave' would look like, even it raises it (like the question of class) accidentally. New Waves' have traditionally relied, of neccessity, on an improvisational DIY aesthetic, but they have also tended to take cinema into the streets. Take out the Dublin accents and Dollhouse might as well have been shot in a studio, theatre, or factory anywhere for all it offers of modern Ireland. In this sense, fortunately, the film is the expection that proves the rule that Irish filmmakers are taking their cameras out and about, but again, that does not, in itself gaurantee a distinctively local film culture. As Sheridan has acknowledged, the improvisational, collaborative, Factory-made approach she used for Dollhouse emulates the one refined in that 'island East of Ireland' by Mike Leigh, Ken Loach, and others. There is some truth to O'Connor's claims that Irish cinema is "finding its voice" and that "there is a new face in Ireland's cinema," but the 'Irish New Wave' he hopes for is equally likely to emulate an approach evident in intimate low-budget British gems like Duane Hopkins' Better Things (2008), Carol Morley's Edge (2010), Scott Graham's Shell (2012), Frances Lea's Strawberry Fields (2012) and Rufus Norris's Broken (2012).

It is odd that Mark O'Connor mentions Ian Power in his manifesto list of those Irish directors driving "a new kind of cinema." Interviewed by IFTN in June 2011, Power discussed his feel-good debut feature The Runway (2010) and talked, like O'Connor, of a wave of young directors determined to shake up the Irish film scene. His 'vision', though, is at odds with O'Connor's calls for a cinema of protest. Power says: "My generation of filmmakers appear to be attempting to make more feel-good, upbeat movies. If you do this, you start to look at having films compete on a global level and not just showing in Ireland to a small audience. Why can't we make Billy Elliot or The Full Monty?" In his manifesto, Mark O'Connor, by contrast, says: "We need to build our indigenous film industry by making it about ourselves instead of trying to replicate the foreign model. For this movement to reach its full potential we need to promote Irish cinema as an important part of our culture and bring this new wave more into the mindset of Irish audiences."

Perhaps what O'Connor puts his finger on is not so much a chimeric 'New Wave' as a simple taking of sides, in which those determined to represent (often unpalatable) local realities resist the happy-clappy homogenisation and shallow 'universality' of globalisation. He seems to be calling for a cinematic contest in which the engaged and politicised square up to the apathetic and apolitical; something like the generational response to corruption and crisis offered by punk in the late 70s. Roddy Flynn and Tony Tracy, in their recent reponse to O'Connor's manifesto**, say that the absence of parents in Dollhouse and What Richard Did hints at a collective local response to the moral and ethical vacuum created by the death of the Celtic Tiger and an era in which "a younger generation finds itself hamststrung by the amoral decisions of an older generation who have left them with a life-long financial debt." The literal and figurative parental absence they locate in Dollhouse and What Richard Did is also, interestingly, a feature of John Carney's Once and Lance Daly's Kisses. Which makes one wonder if Carney, Daly and Sheridan weren't acting on that kind of generational impulse when they founded the Factory. They certainly filled a vaccuum in Irish cinema when they did so. Those who remember Tony Wilson, the Haçienda and Factory Records with affection will recognize a familiar spirit of defiant independence, collaborative camaraderie and creative freedom at the Irish Factory.

The Factory's conveyor belt of actors, directors, producers, technicians and writers is unquestionably turning out talent at an encouraging rate, which can only be good for Irish cinema. Actors and writers would, of course, have continued to pour forth from Irish theatre without any help from the Factory, but Kirsten Sheridan makes a persuasive point when she says it provides a space where actors, whether they arrive from theatre or with no previous experience, can become accustomed to working in front of cameras. Seána Kerslake and Ciaran McCabe, for instance, can be forgiven their minor missteps in Dollhouse as they appeared at the Factory gates as raw recruits to cinema. The apprenticeship they served there vindicates the Factory ethos and Sheridan's sterling work there. Tellingly, both actors subsequently secured roles in more recent Irish films: McCabe went on, first to join Jack Reynor on What Richard Did, then to work with Johnny Ward on Darren Thornton's Two Hearts (2012), while Kerslake appears in Lance Daly's latest film, Life's a Breeze (2013). Cinematic 'New Waves' are built by new directors, working with new actors, and the Factory will continue to produce new talent, even if Ireland never produces a 'New Wave'. History and proverb caution us never to say 'never'. It could be said that the British New Wave was born on Sloane Square, at The Royal Court; the French New Wave was born on Avenue des Champs-Élysées, in the offices of Cahiers du cinéma; the Czech New Wave was born in Prague, at FAMU's famous studios; maybe, just maybe, film historians will one day decribe the Factory on Dublin's Grand Canal Quay as "the birthplace of the Irish New Wave."

* Mark O'Connor's manifesto, Irish Cinema: A Call to Arms:

http://www.broadsheet.ie/2012/07/23/irish-cinemas-new-wave-a-manifesto/

** Roddy Flynn and Tony Tracy's response to O'Connor's manifesto:

http://estudiosirlandeses.org/2013/03/irish-film-and-television-2012/

|