When you die,

You stop drinking beer.

When you die,

You stop being here.

When you die some people cry.

When you die we say goodbye.

Yeah. |

When

You Die – Barnes and Barnes |

Planned

your funeral yet? No? Almost no-one I know has even given

it thought. Sure, they might prefer cremation over burial,

but they leave things like the style and content of their

service to surviving relatives, if they have any. There

are those who are very specific about the manner in which

their passing should be marked and their remains handled.

I distinctly remember many years ago reading about a staunch London socialist

who regarded funeral directors as vultures, and thus specified

that he should be buried in his own back garden in a coffin

made of chipboard, a request carried out by his dutiful

son. Not all suggestions are so seriously minded. Luis Buñuel

once quipped to friends (on camera) that after he died he

wanted his body hung up in the street so that passers-by

could spit on him. Most of us unconsciously avoid the whole

issue of what happens after our death as it entails directly

confronting our mortality, acknowledging on some level that

one day, as the above ditty points out, you stop being here.

Not

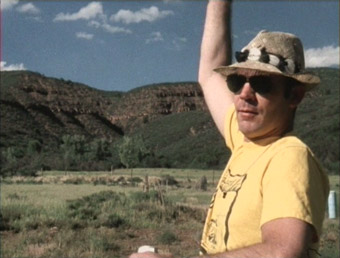

so Gonzo writer Hunter S. Thompson, whose plans for his

own memorial service were elaborate to the point of implausibility,

a last gag on a world that he appeared to enjoy being a

creative thorn in the side of. That those who knew and loved

him were determined to carry out his last request, no matter

how impossible the task may seem, is surely a testament

to his impact not just on friends and family but the community

in which he lived.

Now

before I go any further it might be worth outlining just

what this funeral plan consisted of. The centrepiece of

the service was to be a monument, a 150 foot high steel

arm whose base would be surrounded by a mound of large boulders,

its top bearing the two-thumbed fist that had become the

emblem of Gonzo, cast in steel and weighing over two tons.

The service itself would involve a firework display, the

climax of which would see Thompson's ashes blasted a thousand

feet up into the air in explosive canisters. The very considerable

bill for all this was footed by actor Johnny Depp, a close

friend of the writer and who played him in Terry Gilliam's film

version of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas

(and is set to star in Bruce Robinson's upcoming film adaptation

of Thompson's The Rum Diary).

Behind

the camera recording the preparations for the event was

documentary filmmaker Wayne Ewing, whose twenty-year collaboration

with Thompson resulted in the excellent Breakfast

with Hunter and the fascinating and troubling

Free Lisl: Fear and

Loathing in Denver. It's this long-standing

friendship with Hunter and his family that allowed Ewing

to get so close to a process from which other media personnel

were excluded, to cover every aspect of the monument's construction,

from the design to the casting of the fist and installation

of a LED-lit flower to the building of the giant arm. There's

only one thing missing, a rather important thing in some

ways, but I'll get to that later.

The

construction of the monument required an alliance of the

artistic, the practical and the social, a grand design that

could face local opposition and prove an engineering challenge,

a 150-foot high steel column that would need sturdy guy-ropes to keep it standing and be erected in a field

in which lightning was known to strike (illustrated in a

very nice shot in which both the tower and earthed lightning

are captured in the same frame). In

truth, this dramatic potential soon evaporates due to a combination

of professionalism and good luck. Local permission is readily

granted, the construction of the monument proves no problem

for some first class engineering firms, and the nearest

its assembly comes to difficulty is when the covering canvas

develops a small tear and has to be sewn up. The firework

display is a different matter, the dry weather triggering

a fire ban that forbids even outdoor cigarette smoking,

and the height of the intended display becomes an issue

when the organisers are told that it might potentially conflict

with the flight paths of aircraft approaching and leaving

the local airport.

But

for the most part it's a smooth ride, good news for the

event but stripping the narrative of substantial portion

of its potential drama. Given that the film is a record

of the construction of a memorial this is not really an

issue – it would be a little churlish to complain that the

planning of a funeral service didn't play to the camera

by developing a few problems. What does give the film a

bit of a kick in the shins is it's lack of a climax. Although

the exclusion of cameras is understandable from what, in

spite of its scale, is a private ceremony, all of this extensive

groundwork can't help but build anticipation for a collective

reaction and appreciation that we never get to see. The

fireworks are there, but the faces required to deliver the

emotional punch the event deserves – and no doubt had –

are off in the darkened distance at a party to which we

have not been invited, something that tends to hurt a little

after having been so close to its preparation.

If

you can live with this then When I Die is still a consistently interesting if teasingly incomplete

record of a great writer and individualist's last shout

in a world that too often embraces the mundane and the populist

over the edgily original. If it seems more easy-going

than Ewing's other Hunter Thompson films then that's evidence

of the hole that's been left by Thompson's passing. It still

has its priceless moments, as when a truck driver delivering

part of the monument asks about a man he knows of only through

rumour. ""Who is this writer?" he asks. "Somebody

told me he's into drugs and guns, and could write. Is that

it?" Installation supervisor Dave Baker laughs and

says simply, "My kind of guy."

Framed

4:3 and shot on medium to high-band video – I'm guessing

DV-CAM but I may be wrong – the transfer is up the the usual

standards of Ewing's own DVD releases, with sharpness, colour

and contrast all as good as you could hope for. Obviously

the video format is NTSC, but there's no regional coding

to worry about.

The

Dolby 2.0 stereo soundtrack is always clear, the voice recording

first rate (not always a vérité strong point)

and the typically fine music score very nicely reproduced

– it's here that the stereo really kicks in.

None.

An

engaging record of an 'only in America' event in which the

sheer scale and audacity of the memorial seem wholly appropriate

to the larger-than-life character it is built to commemorate.

The film has definite stand-alone appeal, but is obviously

going to be of greatest interest to fans of the author,

particularly those who've already enjoyed Ewing's other

Hunter Thompson films. Despite being released before Free

Lisl, When I Die represents the

closing chapter in a too-short series – it's just a shame

that circumstances have left this well assembled and appropriately

respectful film without its grand finale.

|