| |

"Tony, the only way you're gonna survive is to do what you think is right, not what they keep trying to jam you into. You let 'em do that and you're gonna end up in nothing but misery!" |

| |

Frank Manero Jr, in Saturday Night Fever, 1977 |

| |

"Raúl represents our irrepressible craving for the modern world while we're sinking it into the ground." |

| |

Pablo Larrain, Sight and Sound magazine, 2009 |

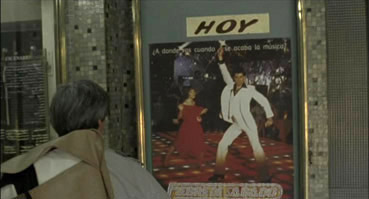

When I saw the poster for Pablo Larrain's Tony Manero for the first time, it made me smile and got a momentary laugh for the Sophie Ellis-Bextor lyric nod in its tagline ('It's murder on the dance floor'). What I really liked, was the juxtaposition of vast, dark background, the bold lettering – writ as large as the reputation of John Badham's love letter to disco, Saturday Night Fever, which inspires this film's lead character. My favourite part is the tiny DIY glitterball in the corner, illuminating the small figure of Tony Manero striking Travolta's infamous pose. It looked like some strange sequel turned parody, with Tony, now older, wiser, less handsome, less suave and definitely more senior, going back to the floor one more time to reclaim his youth. I had visions of it looking something like a Christopher Guest's Best in Show and A Mighty Wind or the rock parody leviathan that is Rob Reiner's This is Spinal Tap. As a fan of all three, to say I was happy about the prospect of car-crash levels of amusement is an understatement.

After a quick glance further down the page, I hit upon the name of the film's director, Pablo Lerrain. Since Tony is only the Chilean director's second feature, I didn't gain much extra in the way of context to pave the way for what the experience of the film might be like. Goalposts of anticipation slightly shifted, I reconfigured my thoughts, wondering if it was going to be something like Emir Kusturica's brash, farcical comedy, Crna macka, beli macor/Black Cat, White Cat or Bigas Luna's Huevos de oro/ Golden Balls, concluding that bawdy and comical are good, but those two elements with a little more bite were much better.

Imagine my confusion, and, well, quite frankly shock when I began to read reviews, which hailed Alfredo Castro's Tony as an anti-hero in the vein of Travis Bickle, who exhibited the sullen sociopathic ways of Richard in Shane Meadows' Dead Man's Shoes. In the space of ten minutes, Tony Manero (the character) and Tony Manero (the film) had boomeranged between America and Spain on its way to Chile, starting out like an accented spin on a Ricky Gervais sketch and ended up looking like a middle-aged Patrick Bateman in flares and platform heels. Though Chilean Disco Psycho has quite a fetching ring, at no point did I ever conjure up an image of a disco-obsessive with murderous intent. However, this is by no means a case of marketing spin gone off the rails, for the dark, bleak world depicted in Tony Manero, it's a perfect sell, for the simple reason that nothing in this film is what it seems.

Set in Santiago, Chile, in 1978, with the country still in the firm grip of General Pinochet, fifty-two year old Raúl Peralta (Alfredo Castro, who also appeared in Pablo Larrain's first feature, Fuga/Escape) lives and breathes all things Tony Manero, spending his days honing his dancing skills in the hope of one day equalling the skills of his silver screen idol. At a local café-turned-bar, Raúl and a small group of friends, including girlfriend Cony (Amparo Noguera), her teenage daughter Pauli (Paola Lattus) and her boyfriend Goyo (Héctor Morales) form a dance troupe, practicing to perform at weekends under the watchful eye of its owner, Wilma (Elsa Poblete). When a television talent show 'The One O'clock Festival Show,' announces they're searching for the Chilean Tony Manero, Raúl seizes his chance to showcase his skills on a larger stage. As the competition nears his obsession with becoming Tony grows, forcing him to go to greater lengths in order to realise his goal.

Right from the start, it's clear that Raúl is a man forever chasing an impossible dream, where everything is temptingly close and yet out of his reach. Raúl is a nobody, borrowing the persona of a somebody in order to better himself. His best is never good enough. As hard as he tries, everything is never quite right: his suit is ill-fitting and messing buttons, his 'disco' floor is clear glass blocks rather than the expensive, coloured version his hero dances upon. Raúl is forever an imitation; he'll never be as good as the original and he knows it. While there's something oddly endearing about his persistence to succeed and something strangely comical about how wrong and make-shift his mock-up dance studio looks.

The comedy within Tony Manero is more likely to make you cringe than make out laugh out loud – more Fellini, less Monty Python. You can't help but feel pity for Raúl or be moved by the inherent tragedy in his story. Even when he performs well on stage at the café, and in the televised dance competition, there's no soaring strings, uplift or pride as with countless sports and dance films; bleaker still, there's no real sense that Raúl has achieved anything, even after all his hard work to get there.

His dancing is the cornerstone of his life and something that he professes to love, dedicatied to 'Le Fever,' to evangelical levels, as if it were a replacement for God, filling the space in his life religion should occupy. The whole experience looks so joyless, it's almost like a penance, and it's hard to understand why he carries on. Dance here is not to much a form of expression – though it clearly provides him with a release on some level – and more an exercise in mimicry. He argues on more than one occasion with Goyo and Cony over the colour and style of their replica costumes, and stubbornly refuses to incorporate Goyo's choreography into their performance routine because "it's not in the film." This attention to detail is much like the meticulous rules a solider must stick to regarding their personal appearance and the countless hours they spend learning the intricate timings of military march formations. He's been doing this so long it seems, his behaviour is engrained.

However, Raúl is a soldier for a country far across the sea. The American culture he's attracted to, and so quick to adopt has infiltrated his country and his brain, changing everything from the way he dresses, the language he speaks and his belief system. In essence, he's become colonised, playing the traditional music from his country behind closed doors, as if it were as contraband, as deadly to be associated with as Goyo and Pauli's underground activities. As a man without any real passion or conviction, Raúl is the perfect cipher. He never shows remorse for his crimes and is entirely morally bankrupt. A loner and a spectator in his own life, he's also separated from his culture and his sense of self. The only sense of perspective he gains is through Cony, his counterbalance. When he suggests there's no place for him in Chile, Cony is quick remind him of his roots, telling him he belongs where he is. Raúl doesn't even appear to take this on board, unaware of how delusional he really is.

Tony Manero is a film about the disparity between what we dream for ourselves, and what our life ultimately turns out to be. It's hard to imagine a fresh-faced Raúl in his prime – probably looking like a carbon copy of Travolta's Manero – as a fifty-something man, stuck in a tiny, dingy apartment playing out the fantasy of being Tony in order to escape the life he leads, masking his shortcomings like a performer does with stage make-up. Tony is everything Raúl is not, but aspires to be: young, free, successful and sexually desirable. The two men are polar opposites in every respect, aside from their common goal of escape. Both men use dancing as a social mobility tool, in order to raise themselves higher, and transcend the confinement of their working class lives. Though this shared intent may be part of the reason why Raúl is so drawn to the character, in physical attributes alone their differences are stark, and for Raúl, undoubtedly painful, translating into the rage which fuels his ruthless, often unjustified acts of violence and cruelty – the only part of his life and world which he has any control over.

The majority of Raúl's failings are a by-product of the culture in which he lives, stemming from the constraints of living within or rather surviving the Pinochet regime itself – most notably the curfew which curtails his freedom around the city – but others are of his own doing. Just when we think he will finally be successful in some way, redeeming his character, Larrain closes off the avenue. His unlikely status as object of desire for the women in the café inflates his sense of self and sexual prowess – feeding into his desire to be a powerful masculine figure. However, his delusions are unceremoniously cut down by his girlfriend Cony, who brands him as impotent. Raul's attempts to rectify the situation and reassert himself fall apart when he tries unsuccessfully to seduce her daughter Pauli. The result on screen is nothing like the grand, effortless seduction Raúl is clearly aiming for. Instead, it's brutally honest, messy, excruciating, perhaps even more unsettling than the cool efficiency Raúl expresses when he indulges his darker, homicidal urges, reflective of the tension between fantasy and reality which runs throughout the film.

Larrain's use of the Fever's iconic imagery only stands up long enough to be torn apart, used as a tool of social commentary, challenging its monolithic status in Raúl world what means to him as much as what it allows him to be– and the wider realms of pop culture – what it means to us and how it represents a particular moment in time. Amidst all the performativity and the artifice of Raúl as Tony, the film is deeply rooted in social-realist traditions, echoed in the film's aesthetic and use of handheld camera – its lens is harsh and unforgiving eye, but tellingly one which refuses to cast any kind of judgment. To complicate things further, the boundaries of privacy are very much blurred. It often feels like we're intruding on Raúl's life, a feeling which only increases when he engages in less socially or morally acceptable behaviour, all completed without a hint of remorse. Though the violence isn't particularly bloody, the sudden nature of it does come as something of a shock.

Just as Travolta's Manero was the spokesperson for a nation, Castro's Raúl stands for a nation, and its infamous dictator. As Raúl wanders through barren-looking streets of Santiago administering his own brand of justice, upon those who have wronged him or the regime it's impossible not to draw correlations between him and Pinochet. Whether he's retailing toward the scrap yard salesman who overcharges him for the glass blocks to make his stage floor or the puerile revenge he takes on young Goyo, when he enters the talent competition himself, they could be dismissed as a knee-jerk reaction to being mistreated, but this isn't always the case. His attack on an elderly lady (whom he earlier helped after she's mugged in the street) for speaking about the dictator, and later robbing a man chased by the secret police, tossing his anti-Pinochet propaganda into the nearby lake, make him look like a strange sort of ambassador-turned-ally for the leader who is absent from the screen but very much present within the film.

The look of Tony Manero is almost the slipside of its inspiration, Saturday Night Fever, shot hand-held and often using available light or practicals and given the dingy, gritty look of a vérité documentary. It's thus a tough one to make look sparkling on DVD, but then to do so would probably detract from the intended aesthetic. Within these restrictions the transfer is sound enough, with the contrast on the soft side to retain shadow information when inside or at night but a little bolder in daylight exteriors, the colours deliberately muted and with an earthy bias, and grain visible throughout. Sharpness is pretty good but not exceptional – again this feels about right for the low key documentary look.

The 5.1 surround soundtrack keeps the dialogue front and centre but spreads the sound effects a little wider, with a few specifically placed to the rear. In keeping with the visuals there is no show-off work here, but it does the job well enough.

Q and A with Alfredo Castro (16:11)

An interesting and particularly enjoyable interview session with leading man Alfredo Castro at the Institute of Contemporary Art filmed on the opening night of Tony Manero, conducted by Maria Delgado, Professor of Theatre and Screen Arts at the University of London. Delgado and Castro interact well throughout, discussing a wide variety of topics, including the genesis of the film, its historical context and Castro's experiences during its making.

Though the footage has clearly been edited down for the sake of clarity and watchabilty, the quality of the content remains unaffected, and is well worth a look for those wanting to learn more about the film and/or various aspects of its production.

Trailer (2:44)

Peppered with some well-placed quotes, this is clearly edited with a bias toward the current vogue for reality television talent shows, which undoubtedly brings some added allure and the possibility of a wider audience. To its credit, it also offers a balanced depiction of the overall tone of the film, including its darker moments.

Also included in the package is in an Introductory Booklet, which was unfortunately missing from my review copy, leaving me unable to add any further comments.

Following the groundswell of critical praise for the film, there's equally significant anticipation for this release, and it will certainly bring in some new viewers on that basis alone. Network have done a fine job here, and while they may have acquired distribution in order to allow the film to be more widely seen, its easy to see Tony Manero turning into a title which achieves cult status, much like Raúl's beloved Saturday Night Fever.

Tony Manero is a film with a dark, dark heart. Part study of the extremes of human nature and part critique of the celebrity-obsessed, fame-seeking culture that has become so prevalent, Pablo Larrain's gritty, unflinching – and sometimes discomforting – take on life under Pinochet rule is an utterly compelling and particularly strong second feature. Alfredo Castro's performance ranks as one of the most powerful and realistic depictions of a misanthropic, alienated man in recent cinema history. Highly recommended.

|