| |

"At some point we have to get out of Hollywood and into here [taps head] and into here [points to heart]." |

| |

Haskell Wexler to his son Mark |

As a young film student specialising in camerawork, my cinematic heroes differed a little from those of my largely director-obsessed classmates. Don't get me wrong, the list of filmmakers whose work I admired included an exhaustive collection of directors, but if you wanted to learn about lighting and frame composition then you really needed to look to the cinematographers, and if you wanted to learn about them in these pre-internet days then you had to reach beyond the fanzines and into the specialist technical publications – American Cinematographer and the like. As with particular directors, I began noticing the work of specific cinematographers when their names kept cropping up on films whose visual style had made an impression, and they would thus get added to a personal list and their work researched and actively hunted out. One of the names that kept cropping up was Haskell Wexler.

My

first exposure to Wexler was through his work on American

Graffiti – I was thrilled by the sights and sounds

of the film long before I learned to appreciate just what

Lucas had achieved as a director. But it is perhaps ironic,

given my comments above, that what really elevated Wexler

to the status of a Film God for me was Medium Cool,

his first fictional feature as director and one that genuinely

expanded my perception of the possibilities of cinema. This

time I was as captivated by the direction as by the camerawork.

Both, of course, were down to Wexler. In the years that

followed it was not just his work that impressed, but his

political commitment, as he actively campaigned for those at

the bottom of the social ladder and against American military

action abroad, and in while his fellow protestors

were cautiously calling themselves liberal, he was openly describing

himself as left-wing.

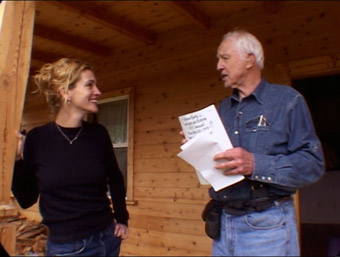

As is often the way, Wexler's son Mark followed in his father's footsteps and became a documentary film-maker, but where his father was using the camera as tool for social justice, Mark was more conservative in his choice of subjects. His first film as director, Me and My Matchmaker, focussed on modern-day Jewish matchmaker Irene Nathan, and took an interesting, Nick Broomfield-style turn when the director became as much part of the story as his intended subject. As producer he was responsible for Air Force One, which charted the history of the presidential aircraft, and in the process he became friendly with some of the very politicians that his father still holds in contempt. For his second film as director he elected to focus on a subject a little closer to home and turned his camera on his father. What could so easily have been an AFI tribute film (watch some of the early interviews in isolation and you could be fooled into believing it is) proves to be much, much more, exploring with compelling honesty the sometimes fractured relationship between the filmmaker and his famous father.

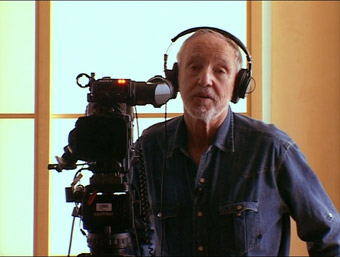

The traditional biographical material is all here, tracing Haskell's career and working methods through voice-over, archive stills, film extracts, and initially glowing interviews with a range of famous faces with whom he has worked over the years, but it's when the fourth wall is shattered that things really get interesting. The opening sequence is a good example of both the technique and the underlying theme, as Haskell shows us some of the camera equipment he is in the process of selling and Mark asks him to tell us where we are, only to have his father cry out in exasperation, "If you don't know where the fuck we are right now...just look around!" He then dishes out a short lecture on telling the story though what you show rather than what your subject says, ending with the advice: "If you get it, that's fine, if you don't get it, tough shit."

It's clear that Mark is in a no-win situation here, a relative newcomer to a craft at which his father is an established master. But complicating matters further is Haskell's own experience as a director and his resultant views on how this film should be made, coupled with Mark's frustration at being constantly overshadowed by his father's fame. The choice of title directly relates to this – what sounds like a director's instruction to his subject is actually something said by Haskell to Mark once to encourage him to introduce himself to someone. "Tell them who you are," he said, actually meaning, "Tell them that you're Haskell Wexler's son." As Mark states early on in the film, "I am the son of a famous father, and I have spent much of my adult life struggling to step out from under the shadow of that fame."

The

problematic relationship between the two men is initially

established by their respective opinions of their own filmmaking

skills. Haskell clearly has a low opinion of many of the

directors he has worked with, suggesting that most of them

were "idiots" whose films would have been better

if he had directed them, while Mark remains uncertain of his own abilities.

This is most effectively illustrated by his footage of his father's 80th birthday party, where he is intimidated

by the presence of so many famous filmmakers, including his own

father – when George Lucas tells Haskell that the camera

Mark is using is what you should now use for television,

Haskell retorts that the only weakness of the equipment

is the what lies behind the camera (pointing at

Mark) and his decision not to employ a separate sound operator.

As if to justify this put-down, Mark then admits

that by trying to do everything himself, he was unaware that the connection between the microphone and the camera had failed, resulting in two hours

of footage in which the anecdotes of the guests are lost

to a technical malfunction. It is telling that he chooses

not to reveal this information to his father.

It becomes clear that Haskell's sometimes acerbic personality and need to be in control have not only annoyed some of his colleagues – Norman Jewison describes him as "a pain in the ass to work with" – but have lost him jobs. The evidence, as presented here, suggests he has not mellowed in any way. His professed enthusiasm for a documentary about him that explores the man beyond the Hollywood image is confounded by his refusal to sign the required release form until the final film has met with his approval, while his cantankerous attitude to Mark, or at least the one he likes to present to others, is twice caught on tape when he believed Mark was no longer filming.

But

Haskell's fierce conviction to his politics (his delight

at meeting Weavers singer Ronnie Gilbert at an anti-war

demonstration is infectious) and his overriding humanitarianism

becomes increasingly endearing, certainly more so than his son's non-committal conservatism.

Mark wants to use the film to get close to his father and

explore all aspects of his personality, but bottles out

of accompanying him to a political meeting out of fear

that this might lose him a job filming George W. Bush on

Air Force One, and his request that the two not talk

politics as they travel to an anti-war rally is met with

understandable disdain. This reaches a revealing climax

when Haskell invites Mark to his hotel room because he has

something important to say to camera, only for the two to get into an

argument over where the piece should be filmed. Perhaps the

intention was to show just how stubborn the old man can

be, but while Mark continually badgers his father to relocate

the interview to the balcony, where the light and the background

will be more attractive, Haskell refuses to budge on the

basis that what he has to say is more important than how

the shot looks, a crucial lesson in documentary film-making

that at this point appears to be falling on determinedly

deaf ears.

Whether his father's advice finally hits home or whether he was just being deliberate provocative all along is hard to say, but by the end of the film Mark achieves the task set by his father in the opening quote of this review, most movingly realised in the heartbreaking scene where the pair visit Haskell's ex-wife and Mark's mother Marian, now in the grip of Alzheimer's disease. Their differences remain unsettled, but there is the sense that in the process of making the film, they have got to know and understand each other a little better. But this is far more than cinematic father-son therapy, making as it does for consistently fascinating and enlightening viewing, laudible for its detailed look at Haskell's impressive career, for the sheer range of interviews with key industry figures (the list is too long to detail here), for its winningly off-guard moments, for its touches of warm humour, and for its unsentimental humanity. Most effective of all is its honest and ultimately touching look at the man behind the legend and the nature of the his relationship with his son, a thoughtful and revealing journey into the private world of the head and of the heart.

Shot largely on DV-CAM, the transfer here has been taken straight from the video master rather than the film transfer and looks close to pristine, with excellent sharpness, contrast and colour, particularly impressive given that this is a PAL transfer from an NTSC source. The distinctly video look may not be everyone's cup of tea, but is most appropriate to the documentary format. The picture is framed 4:3, the correct aspect ratio.

There's not a lot to say about the Dolby 2.0 stereo soundtrack – it's very clear, the music is very nicely reproduced and it has no reason to show off. Functional in the very best sense of the term.

It's hard to say exactly what could have been included in this section, but for some the quantity and quality of the extra features are an important element in their decision to buy, at least at full retail price. In this case they'll find little encouragement here, as all that's included is a Trailer (2:36), which does its job well enough.

Though the lack of extra features may disappoint some, Tell Them Who You Are is nonetheless an excellent example of the personal documentary at its most informative and involving, and one that should have immediate appeal to cineastes everywhere, being a portrait of a great filmmaker, and a fine film in its own right. Technically the disc is hard to fault, and if it's the film alone you're after then you'll have no complaints here.

|