|

I

have to admit to being only vaguely aware of Kinoshita Keisuke's

Nijushi no hitomi [Twenty-Four

Eyes] before the announcement of its UK DVD release

by Masters of Cinema. As a confirmed devotee of Japan and its cinema, I realise I should have

known all about the film and have seen it some time ago,

but there are only so many hours in the day and so

many films to see, and some of us have to make a living

as well. And, of course, I'm English. I mentioned the title

to a friend who grew up in rural post-war Japan and her

eyes lit up. "You've got it?" she asked eagerly.

She knew Sakae Tsuboi's original novel well, and though

she had never seen the film, she was aware of its fame. As well she

might be. Back in 1955, it won the Golden Globe for Best Foreign

Language Film, and Kinema Junpo magazine selected it as

the year's Best Film, beating – wait for it – Kurosawa Akira's Seven Samurai [Shichinin no Samurai] and Mizoguchi Kenji's Sanshō Dayū.

That's right, the Japanese film industry believed it was

an even better film than Seven Samurai,

one of my very favourite films. How the hell

is it that I hadn't seen this before?

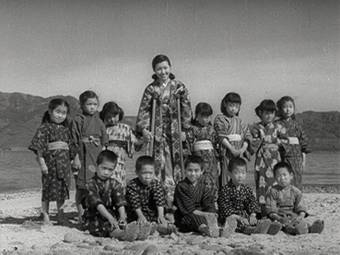

Set

on the inland sea island of Shodoshima, the story kicks

off with the arrival of new schoolteacher Oishi to

an isolated coastal village. Treated with contempt by the

older locals for her city-influenced clothing

and because she rides a bicycle, (necessary to cover the considerable distance from her home to the school in

which she has been engaged to teach), Oishi nonetheless

quickly connects with the young students, who soon become

devoted to their new teacher.

Watching

the film with my friend was a surprisingly touching and,

for her, nostalgic experience. She sang merrily along to

all the children's songs and even supplied words for several

of the instrumental pieces. She recognised many of the activities

and pointed frequently at the screen with the delighted

cry "I used to do that!" She also provided an

insight into scenes that, as a western viewer, I would otherwise

not have fully appreciated. A good example is the

sequence in which the children are being taught the musical

scales by Oishi's more old-fashioned employer. In an attempt

to provide an English equivalent for the spoken (or rather

sung) Japanese, the subtitles translate "hi

hi hi, fu mi mi mi, ii ii ii mu ii" as the more familiar

"doh doh doh, rei mi mi, so so so lah so" But

it is the teacher's refusal to use this globally accepted

western equivalent that is key to the scene – it is of English

origin, not Japanese, and therefore at this time and in

this community is something to be rejected.

It

is this very attitude, of course, that prompts the initial

hostility to Oishi on her arrival in the community, dressed

in western-style clothing and riding a vehicular import,

a reflection of pre-war rural frustration at the encroachment

of western values into Japanese society, something that

had already taken serious root in the cities and larger

towns. The children have yet to learn such judgemental attitudes,

and Oishi is able to communicate with them almost from the

moment she steps into the classroom, encouraging a lively

response to questions, leading them in outdoor sing-alongs,

and calling them by their nicknames, which she writes in

the attendance register.

But

what starts as a tale of an outsider's battle against small

town prejudice soon considerably widens its scope and thematic concerns.

The relationship between Oishi and her students is used

to examine Japanese social and political history in the

period leading up to, during, and immediately following the

Second World War. The children in particular are at the

core of this, and in the first half are just

about the only characters photographed in close-up, something

Kinoshita uses beautifully to connect us to them as individuals.

These young hopefuls represent both traditional thinking

– the boys who dream only for fighting for the Emperor –

and the changing times to come, as with the girl who writes

in her 'Hopes for the Future' essay of a Japan in which

women have regular jobs, and by association equal standing

with their menfolk. In this telling scene, one girl is unable

to write anything at all, as imminent bankruptcy has left

her family bereft of optimism.

Fate

certainly deals all of them a tough hand in these turbulent

times, as one girl falls victim to tuberculosis, another

is sold by her family into servitude on the mainland, and

a third leaves the island when their family is evicted.

The boys fare no better. Enthusiastically going off to

war to fight for their emperor, not all are destined to

come back alive, and one of them returns robbed of his sight. Oishi

is equally fated. Accidentally injured when a student

prank that backfires, she is instantly disconnected from her job and her

students through her inability to ride her bicycle to the

school. She later takes up teaching again at the larger

consolidated school, but by now is becoming disillusioned

with her profession, almost branded a communist for attempting

to widen her students' knowledge of politics, and a coward

for her dismay over young lives wasted by war. Although

she verbally protests, she remains effectively powerless

throughout, anguishing over events that she is unable to

prevent or affect.

The

authenticity of the activities which my friend so cheerily

recognised is perhaps counterbalanced a little by some artistic

licence when it comes to the portrayal of Oishi. Sato Tadao,

generally regarded as Japan's foremost film critic (and

the one Joan Mellen references in the accompanying booklet),

described her as "an idealisation" and says "I

can't remember any primary school teachers like Miss Oishi.

Even if any such people had really existed then, they would

probably have been forced to resign."* Not that this

really matters. Oishi is very much a post-war creation,

a symbol of a strong pacifistic element in Japan that was

opposed to rearmament, but also a voice that speaks for

a generation of young men lost to war, and a plea for

peace to present and future societies.

In the accompanying

booklet, Joan Mellen states that the final scenes of

the film are moving but not sentimental and that the film

as a whole bears no trace of sentimentality. I'm not so convinced, and

Sato Tadao himself has accused the film of sentimentalising

the anti-war issue. There is a very real emotional power

to much of the film, but it too often seems to rely on characters bursting

into tears, especially Miss Oishi, who in the final scenes

barely makes an appearance in which she is not crying at one point,

something that lands her the nickname 'Cry Baby' from the new generation

of young pupils. Pushing it just a little further over the

edge is the almost Hollywood-esque use of emotive western

tunes such as Annie Laurie, Auld Lang Syne

and There's No Place Like Home, which can feel

a tug too far at the heart strings. This is well illustrated

in the scene in which the boys go off to war – as they depart,

it's the faces of the boys, heroically framed but emotionally

vulnerable, that give the scene its emotional power, not

Oishi's tears of sadness. (I should mention here that I'm

not in any way imune to the effects of emotional cinematic

manipulation, and blubbered uncontrollably at the end of

Isao Takahata's Grave of the Fireflies.)

But

there is still a so much here to admire and enjoy, not least

in the quality of the film-making and the scope of the story,

which provides a fascinating insight into a pivotal moment

in Japanese history, albeit from a post-war, humanist perspective.

There are some beautifully handled scenes, most of which

involve the children at various stages of growth and development,

from the editorial linking of names to faces when Oishi

looks over the children's calligraphy, to the long walk

the pupils embark on to see their injured teacher, a demonstration

of their unity and fortitude that ultimately results in

Oishi's acceptance into the community. The island landscapes,

often gorgeous in themselves, are as much a character in

the film as any of the children, and are as crucial to the

narrative as the dried fields, narrow paths and open waterways

of Shindo Kaneto's The

Naked Island, and scene after scene demonstrate

Kinoshita's extraordinary eye for composition and camera

placement, and his understanding of the power and pace of

editing.

For

the most part, Twenty-Four Eyes is handsome

cinema, an involving, ambitious and sometimes strikingly

made work that is both epic in reach and intimate in approach,

but whose effectiveness as a tear-jerker will depend on

your reaction to the surplus of in-film expressed emotion.

But better than Seven Samurai and Sansho

Dayu? Not quite, at least in my book. It is nonetheless

still held in extremely high regard in its native Japan

and in 1999 was selected by Japanese critics as one of the

ten best Japanese films of all time. I'll thus let my friend

have the last word on a work that she was able to relate

to so much of. "It was a really nice film," she

told me, "but I still preferred the book." Ain't

that so often the way.

Of

all their recent DVD releases, it's the ones sourced from

the Shochiku studio that seem to have given Masters of Cinema

the biggest headaches, in the main because of what seems

to be the shoddy condition of the prints they have been

given to work with. Twenty-Four Eyes is

in some ways no exception, with a great deal of visible

wear and tear, print damage, and brightness instability.

There are scratches and dust all over the place, but – and

this is a notable but – there has been a commendable attempt

to reduce the visibility of these imperfections, and a largely

successful one – although still present, they are nowhere

near as distracting as you might think. This is due in no

small part to the transfer's surprisingly fine level of

detail and sharpness and generally excellent contrast, lifting

the picture quality well above those on the MoC discs of

Scandal

and The Idiot.

There are a couple of night scenes in which the black levels

turn decidedly grey, but on the whole this is a very pleasing

restoration of seriously imperfect source material.

The

mono soundtrack shows its age, being a little fluffy in

places and accompanied by a little background hiss, but

is otherwise clear and free of alarming pops.

The optional English subtitles are activated by default.

Only

one on the disk itself, and that's a Gallery

of original Shochiku promotional material, and it's a substantial

collection, being something like 60 production photographs,

all in fine shape and all reproduced at a decent size.

No

Masters of Cinema release would be complete without an accompanying

Booklet, which here is of the

usual high standard, featuring quality reproductions of

stills from the film and a sizeable essay by Joan Mellen,

who is clearly a huge fan of the film and covers it in impressive

detail. She is not as smitten by the book as my friend,

it has to be said, though does usefully highlight some of

the key differences between it and the film.

Subjective

issues of sentimentality aside, this is a hugely impressive

work that has never been made available for home viewing

in the UK before, and so this DVD release is particularly

welcome. It should be essential viewing for anyone interested

in classic Japanese cinema, or just great cinematic storytelling.

And let's face it, not everyone is as cynical about cinematic

tearjerkers as I am, and judging from reaction across the

web, there's a reasonable chance that by the end you

may have a handkerchief to your face and be trying to convince

those around you that you have something in your eye.

Masters

of Cinema have worked small wonders with what is obviously

a less than ideal print, and despite the print damage the

contrast and detail are very good. Not many extras, but

the disc still comes warmly recommended.

*

Currents in Japanese Cinema by Sato Tadao, translated

by Gregory Barrett, 2nd printing, published by Kodansha

International Ltd, 1987.

The Japanese convention of surname first is used for Japanese names throughout this review.

|