|

If

your concept of Eastern European cinema involves films filled

with long silences, sombre conversations, bleak windswept

landscapes, grubby interiors and unhappy-looking peasant

types, then Sátántangó

will only serve to confirm your prejudices. It's loaded with

them. Oh, and it's in black and white, so the bleak looks

REALLY bleak. If you won't watch these films because you

expect them to move at a snail's pace and have long takes

in which nothing much happens, then you're really going to

have problems. Shots here can run for up to ten minutes

apiece, will often feature just one person doing one thing,

and will frequently be free of dialogue. Have I lost

you yet? No? Well try this on for size. It's seven hours

long. You heard me. That should whittle down the pack a

little. Still interested? Good. Now we can talk.

Sátántangó is set in a small

rural farming community in post-communist Hungary. The autumn

rains have begun and activity within the village has ground

to a virtual halt. Early one morning a church bell begins

to toll, even though there is no functioning church nearby,

and after the sun has risen, a figure wanders into shot

to investigate. At this stage we don't know who he is, where

he is, or even in this light what he looks like. By this

point we are just two shots and twelve minutes into the

film, and you soon realise that information is going to

be slow and often unclear in coming. Over the course of

the next ten minutes we discover that the man is named Futaki

and the woman he is with is not his wife but that of his

neighbour Schmidt, whose sudden arrival home sends Futaki

scurrying to the back room. We overhear that the community

has a sum of money and that Schmidt is planning to run away

with his share. We know little about the money itself or

its purpose, and just as we might be getting close to finding

out more, a new chapter begins. We're forty-one minutes

in by now, a third of the average feature film running time. Here

we've barely scratched the surface.

In

the second chapter, we are introduced to Irimiás and

his cohort Petrina as they walk down a wind-blown road towards

what at first seems like a hospital but is eventually revealed to be a government building, possibly a police station. Here, the two are grilled by an unnamed uniformed official and given a lecture on order, freedom

and collaboration. The

pair are humble and obliging, but once back outside they display a

more self-confident and authoritative swagger. Irimiás

is on his way back to the village, and when news of his

impending return reaches its inhabitants, apprehension spreads

like a virulent flu.

And

so it continues. There are twelve chapters in all, told

from differing viewpoints with overlapping narratives –

the story progresses in linear fashion, but the start of

a new chapter may move events back a few hours to replay

part of the previous chapter from a different angle. The

narrative itself is for some time ambiguous in structure

– halfway through I began to suspect I was now watching

events that occurred before those of the opening

scenes, a view I later had reason to reverse. Not that this necessarily

matters, as it becomes increasingly evident that storytelling

in anything approaching a traditional sense is not what

Sátántangó is all

about.

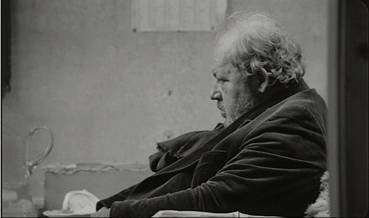

This

is perhaps most evident in the Chapter titled Know Something,

in which we watch the community doctor – an appalling example-setter

who drinks and smokes to excess and wheezes his way around

his house – as he observes and makes detailed notes on his

neighbours, falls flat on the floor and then recovers from

what we assume is a diabetic attack, then runs out of booze

and walks a considerable distance in the rain to get more. This sequence plays

out pretty much in real time, contributes only minor details

to the unfolding story, and is in absolutely no hurry

whatsoever. Thus when the doc nods off, we watch him sleep.

When he walks off into the gloom, we follow him the whole

way to his destination. This unblinking approach invites

us to observe him with the sort of unwavering concentration

and attention to small detail that we simply do not do in

real life. To what purpose? Ah, well...

Sátántangó

arrives on UK DVD having already been proclaimed in many

quarters since its 1994 release as a masterpiece, a label

the more critical viewer should consider it their duty to

be ready to challenge. It's strikingly photographed, rejects

formal storytelling techniques, and appears to be about very

little, but could, with the viewer's collaboration, be about

a great deal. It hails from Hungary rather than a more cinematically

populist region, and it's far longer than even the most

laborious western film, which will effectively dissuade

all but the dedicated from seeing it and contributing to

the discussion. But does that even make it good, let alone

a masterpiece? Doesn't that make it boring, pretentious

and self-important? Is the sense that there are more layers

of meaning than the surface suggests the result of the viewer

projecting their own, dreamed-up interpretation onto an

effectively blank canvas? It certainly looks meaningful,

so surely it must be. Mustn't it? I've just spent seven

hours of my life watching the bloody thing, so it must mean

something, surely!

Before I go on I should say that all of the above thoughts

did occur to me while I was watching Sátántangó.

There were moments in the first third where I began to sense that the Emperor's clothes were not quite as fine

as his courtiers were assuring him they were. But somewhere in the

first three hours of watching the film – I can't mark the

precise point because I don't think there was one – I found

myself strangely and completely hooked. Maybe it takes time

to adjust to the film's pace and fascination with still

moments, with the way it locks onto faces and asks us to

do likewise. It seems to want us to search for the story

behind that expression, behind what happened in the months

before Mrs, Schmidt came into the bar and sat down at the

table to stare off into nothing, her concentration only

broken by the need to investigate a smell coming from beneath

the table.

The

most remarkable example of this technique is also one that

almost sabotages itself. A young girl is tricked out of

what little money she has, and on returning home is ordered

by her mother to sit outside on a chair that has clearly been set up for

that very purpose. A short while later, she crawls into a barn

and we watch her wrestle and threaten a domestic cat, and

in her face and in her voice we see and hear the parental

indifference and verbal and physical abuse she has suffered

for years, together with the despair that is eroding her will to live.

It's a powerful and affecting scene, but the problem is

that the animal she is re-enacting her mistreatment on is

a real cat undergoing real abuse, and my sympathies for

the girl's predicament (which, let's be fair, is performed,

albeit with total conviction) ended up secondary to my concerns

for the animal she was pulling about. Thus, for a while the

scene becomes about the making of the scene, as I was dragged

out of the story and into the process of creating it. This

is made worse when she forces the animal to drink poisoned

milk and watches it die, something that certainly looks

very much for real, and handily provides a dead cat for

her to carry in the shots that follow. If you can deal with

this then you'll witness minimalist filmmaking at its most

troublingly effective, but it's likely to send animal lovers

reaching for the fast-forward button. It is this chapter

also that provides the most memorable narrative crossover

point, as the girl stops by a window to watch the haphazard

but exuberant dance taking place within, an event we later

witness from inside in its entirety in one long, slow-moving

and utterly compelling shot, interrupted only for a cutaway

of the girl looking in from outside, her despair and dislocation

from the other villagers painfully evident.

There

is the sense at times that we are being asked to look not

just at the content of a shot but its execution, to appreciate

its artistry of the filmmakers, and certainly there is a

great deal to admire here. Gábor Medvigy's black-and-white

cinematography is brimming with divine compositions and

beautifully executed camera moves, including stedicam work

so solid that you'll have trouble telling it from the on-the-rails

tracks. So many of the shots lodge hauntingly in the memory,

whether it be the long opening drift through the farm, a

slow and measured track up to a perched owl, or the impossibly

long circling of two policemen as they doctor and type up

a letter from Irimiás. There's barely a shot in

the entire film that does not leave you wide-eyed at the

care with which it has been planned and executed. Most compelling of all are the tracking shots that follow

or precede the characters as they walk, ride or, in a sudden

and almost jarring return to the modern world, drive. Even

though there is a peculiar artificiality to some of these

sequences – as characters walk down a furiously wind-blown

street and drive through the rain I was very aware of

the wind machine and hoses used to create the weather effects

– they are still so striking as imagery and effective in

their subtexual suggestion that they become storytelling

techniques in their own right. This is most pronounced when

we are moving backwards watching the faces of characters

as they move, with the young girl's long walk with her dead

cat once again proving the most haunting and emotive of

all.

These

sequences inevitably recall the 'walking movies' of late

era Alan Clarke and prefigure the more recent work of Gus

Van Sant, whose Elephant and Last

Days achieve a similarly hypnotic hold while

little is seemingly taking place. It would not be a stretch

to suggest a Tarkovsky influence either, although this is

more down to the look and feel than the storytelling technique. Sound

is also most effectively used (the strangely distorted church

bells and the hum in the café that so angers Irimiás

have an almost Lynchian quality to them), and combined with

the emotive visuals and some fine performances create a

treacle-thick atmosphere and sense of place that is increasingly

seductive, dragging you into a world of strangely logical

inactivity, where people wait for possible salvation at

the hands of a man they are prepared to believe in but still do not trust. It's with good reason, too – Irimiás

may have the Jesus beard, appear to have risen from the

dead, and be able to deliver a sermon of hope, but he represents

the darker side of the new capitalism and is poised like a vulture to feed

off the unwary.

So

does Sátántangó justify

its seven hour running time? Well in a way it does. If you

take a sixty minute story and present it in this manner

and at this pace, then it's going to take seven hours to

do so. But by telling this story at this speed and in this

way, director Béla Tarr so drastically alters the way we absorb

and interpret the supplied information that

time measurement is effectively altered for the viewer.

Despite long periods of seeming inactivity, the result is

never boring and is often mesmerising, and hard though this

may be for some to believe, it does not feel overlong. I'm

not sure I'm ready to go with the masterpiece label that

has been applied elsewhere, as for all its considerable

qualities I still can't help thinking that its messages

and meanings are a little too much in the eye of the beholder.

But it's still a bold, unique and gorgeously made film that

offers a very different viewing experience from the movie

norm, and that alone is to be enthusiastically applauded.

The

non-anamorphic transfer is framed approximately 1.68:1 and

is generally of a high quality, with detail very good and

contrast bang-on at best, although some scenes display a

narrower band of the greyscale where black levels are virtually

non-existent. Clean for the most part, there are a couple

of dust spots here and there, a not too intrusive scratch

on one shot and a little side light leakage on another.

On the whole, though, a decent job, though anamorphic would

have been nice.

The

Dolby 2.0 stereo soundtrack has no show-off separation,

but is crystal clear, particularly on sound effects such

as wind, rain and, erm, flies.

All

that's on offer here is a Béla Tarr filmography.

Although

it took me a while to synchronise with the film's pacing,

once there I found it a very comfortable and sometimes inspiring

place to be. In order to check something in this review,

just half-an-hour ago I put the first disc on again and

found myself instantly hooked, noticing small things I didn't

pick up on the first time around. There's no doubt that Sátántangó

presents a challenge for the viewer, but if you're up for

it then you're in for a film experience quite unlike any

other.

Artificial

Eye's 3-disc set lacks any notable extra features and it's

a shame that the picture is not anamorphically enhanced,

but for the most part serves the film well.

|