|

There's a fine line between intrigue and irritation when it comes to shots that are held for longer than is theoretically necessary, a technique favoured by what has been unpoetically dubbed 'Slow Cinema'. The technique's supporters point out that these lengthy and sometimes action-free shots allow you to organically absorb potentially important fine detail without spoon-feeding you with explanatory close-ups and spoken exposition. A more dismissive view might suggest that by holding these shots at such length, a wily filmmaker is able to artificially expand a fifteen-minute story to feature length, and in doing so pull an Emperor's New Clothes-style con on cineastes desperate to latch on to anything that kicks against the mainstream. I wanted to get that out there from the off because that second one is a viewpoint that I do understand and even have some sympathy for but do not happen to share. A look at Slow Cinema's Wikipedia page (and yes, it does have one) quickly confirmed why, as included on its list of 'examples of notable slow works' are a good many films that I greatly admire, and have even covered a few of them for Cine Outsider.

Given that the effect of these shots is audio-visual, actually putting what makes them so arresting into words is harder than you might think. Take the opening shot of György Fehér 1990 Twilight [Szürkület], which consists of a gently drifting top-down aerial view of dense woodland, shot in gloomy monochrome and underscored by an unsettlingly ominous drone. It may not sound like much but I was instantly hooked. The camera then tilts slowly up to observe the grey and mist-shrouded landscape beyond, an image it holds on for an uneventful 60 seconds. This is followed by a shot taken from the front passenger seat of a vehicle being driven through the Hungarian countryside, looking back at two silhouetted and unidentified passengers. How long do you think such a shot should last? Ten seconds, maybe, before we cut to an exterior view of the vehicle, or one that reveals a little more of its occupants' faces? Nope. The shot runs for almost four minutes, and the camera keeps rolling when they reach their destination, panning slowly to watch as they exit the vehicle and slowly make their way up a nearby hill in expressionistically mood-setting heavy rain. The dialogue between them is sparse, as one apologises to the other for dragging him into this "filthy business" in his final days and admits that he doesn't know who they'll get to replace him. When they exit the car, we briefly catch a glimpse of one of their faces as he puts on his hat, but otherwise the framing is so tight that only their midriffs are visible. Here they are met by another nameless figure, who provides some clarification when he says, "Greetings, Inspector," then adding, "By the cross up there. A girl, about eight years old. Most likely been dead for days." It's then that the Inspector speaks, asking pertinently, "How was she killed?" "With a razor" the anonymous policeman replies. As the Inspector walks out of shot, the camera remains focussed on the rain and muddy ground until the second detective exits the car and follows. As he exits the frame, the camera slowly turns to observe from a distance as the three men climb the muddy hill to the site of this grisly crime.

In stripping a familiar situation – a detective on the verge of retirement is asked to assist with a difficult case – back to its bare essentials, Fehér makes it feel as if we're watching such a story for the very first time. Although the scene is set for a theoretically familiar tale, nothing about how the film unfolds plays remotely to convention or (largely Hollywood-fed) expectation. Indeed, for the average viewer – if there can honestly be said to be such a thing – Twilight [Szürkület] is likely to represent a considerable challenge, and I'm not talking about content but the manner in which the story is told. When I noted above that Fehér favours long takes, and I'm talking shots that run for anything from two to six minutes, sometimes with only minimal movement of characters and camera. I may be off by a shot or two, but on my count, there are only 41 shots in the whole film. For context, there are three or four times that many in a single typical modern-day Hollywood action sequence, and to connect with Fehér's film thus requires some adjustment. Just a few scenes in, long before I got to the special features, I was strongly reminded of the films of Fehér's fellow Hungarian, Béla Tarr. Only later did I learn that Fehér and Tarr were not only good friends, but Tarr is credited as a consultant on this film, and Fehér was one of the three producers of Tarr's seven-hour 1994 magnum opus, Sátántangó. As it is with Tarr's cinema, Twilight requires you to adapt to its tempo to fully appreciate what it has to offer. But wait, there's more.

Fehér's screenplay is based on writings by Swiss author Friedrich Dürrenmatt, and while I've not read the source material, it's clear that it's been seriously pared-down for this film,* stripped not just to its bare essentials, but of sizeable chunks of the story and character detail. This renders Twilight as a jigsaw missing over half of its pieces, and while the ones that remain show small parts of the overall picture, some are more detailed and revealing of it than others. Close attention must be paid to every such scene and how it relates those around it if you're going to make sense of what remains, and like Tarr's films, considerable patience and attentiveness on the part of the viewer is required. As the story unfolds, we become like the detectives in the film, required to examine the evidence and draw our own conclusions, using what we learn to help clarify a case that may ultimately have no easy answers. I freely admit that I was two viewings in before the dots really started to connect, and I still needed a gentle nudge from the special features to clarify a couple of key points. As someone already well acquainted with the cinema of Béla Tarr, the slow pacing and long-held shots were not a problem. Indeed, these sequences and the haunting music that underscores them (sourced from Béla Bartók's Bluebeard's Castle and the soundtrack of Werner Herzog's 1979 Nosferatu the Vampire) acted as an instant hook for me, and exerted such a hold that having to pause the film briefly to answer the door frustrated me more than it would normally – it momentarily broke the mood, took me out of the world in which I was becoming deeply immersed, despite the initially disorientating temporal jumps.

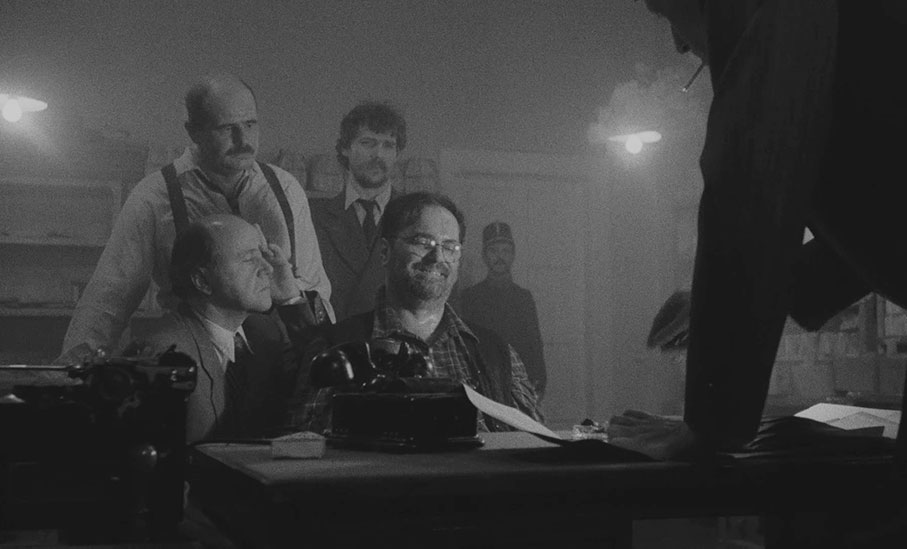

As the film progressed, I became increasingly caught up in the process of interpreting the content of those jigsaw pieces and connecting them to each other with ones of my own creation. Some are clear enough to make it relatively easy to fill in the gaps, such as the scene in which the Inspector (Péter Haumann) delivers an angry lecture to his colleagues in the house of the unnamed hawker (Gyula Pauer) who discovered the child's body, outside of which stands a large group of silent and immobile townspeople. The nearest the film comes to a generically standard sequence occurs a short while later when the hawker is interrogated at the police station, as questions and accusations are thrown by small posse of detectives at a man whose intermittent smiles could be taken either as a sign of guilt, self-confidence, discomfort, nervousness, or straight-up disbelief at his predicament. As the scene concludes, there is even a suggestion of the sort of police corruption that was a mainstay of American police dramas of the 1970s, and certainly an aspect of police behaviour under totalitarian rule.

Questions are raised by the film that are not so straightforwardly or even indirectly answered. Why, for example, does the Inspector silently hide and observe the retiring detective (identified only as K in the cast list and played by János Derzsi) as he breaks the terrible news to the murdered girl's parents, and again when he interrogates one of the girl's young classmates? Does he distrust him? Is he trying to learn from him without interfering? Later, after K has retired from the force (something never shown and obliquely revealed a brief conversation he has with the Inspector), it seems clear that the case has become an obsession for him and he is perusing his own, independent and morally questionable lines of enquiry, determined to keep a promise made to the girl's distressed parents that he would catch the killer. By this point, the Inspector no longer wants his help and regards K's solo efforts as a potential hinderance, repeating to him the angry assertion he delivered to his underlings earlier about the need to maintain order.

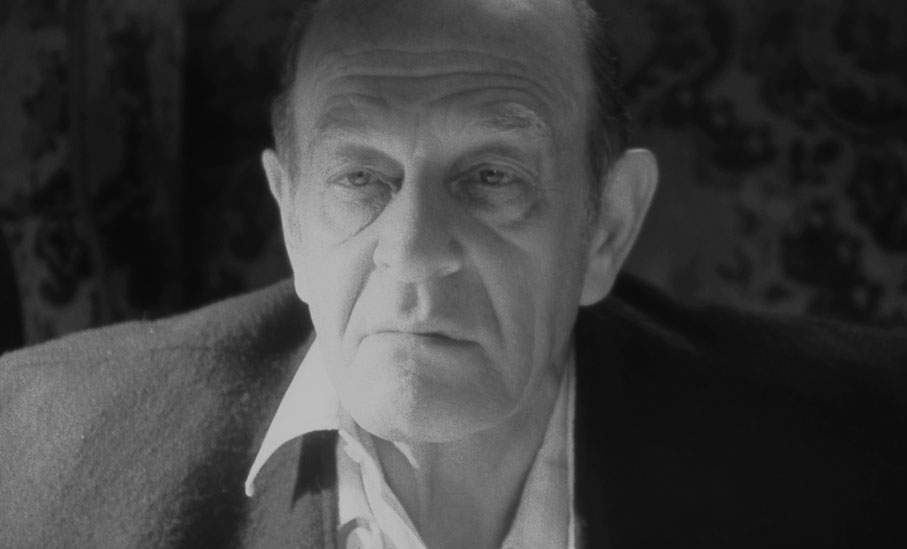

Atmosphere trumps narrative here, with gloomy greys of Miklós Gurbán's monochrome cinematography creating a world so darkly oppressive that it's hard to imagine a situation in which anyone has a moment of real joy. It also has a curiously timeless quality, making it hard to pin down precisely when it is set, the dour clothing and outdated vehicles almost symbols of the pragmatism of post-Soviet Union era Eastern Europe. But this is no simple mood piece, as despite the lengthy scene-setting shots of woodland and rainfall, Fehér's camera returns repeatedly to focus of the faces of his characters, often to a revealing and sometimes troubling degree. Thus, when the Inspector confronts his fellow officers about the mob gathered silently outside the hawker's house, we never clearly see the men he is berating, but learn quickly about what differentiates the Inspector from them through the intimidating stare that he flashes the officer who makes an accusatory remark to their as-yet uncharged suspect, and how confrontationally closely he positions himself to the man to deliver it. Conversely, K tends to be observed in wide shot or from behind, and when he individually interrogates two young girls – the first a schoolfriend of the dead girl, the second the daughter of a woman he has moved in with after leaving the force – the camera remains locked unwaveringly on the faces of the children. If the first of these feels a little uncomfortable, with the girl held firmly by the shoulders and showing signs of disquiet as K repeatedly instructs her to look him in the eye, that's small potatoes compared to what unfolds in the second. Here, the line between child killer and investigating (former) detective starts to worryingly dissolve, as K almost sensually caresses the girl's face, and even at one point places a chocolate in her mouth to bite on, a confection that may be a clue to the killer's identity. So disturbingly intimate is this sequence that I genuinely could not decide whether this was K's standard method of interrogation, or if he was putting himself in the mind of the killer à la Red Dragon's Will Graham, emulating the murderer's grooming technique to tease information from the girl, or whether this was a sign that he was in fact the killer. The one time that K is shown in facial close-up, the shot is held for almost two minutes straight as he stares through the camera without saying a word. Just as I was starting to question what this image was telling us about him, the answer arrives unexpectedly from off screen, and what follows as troubling in its content and implication as the interrogation of the child that shortly follows.

For many, Twilight will doubtless remain impenetrable, and for those who like their narrative cinema straightforwardly told and briskly paced it will likely even prove tortuous viewing, but I'm guessing they're not the sort of people who find themselves drawn to a site like ours. If you're already a fan of Slow Cinema, then you're likely to already be receptive to Fehér's distinctive approach. If, like me, you find yourself captivated by the film's style but initially a little thrown by the narrative puzzle pieces, then my advice is to ponder on what you have seen, and then give the film a second look, as for me that's where it all really fell into place. That said, there was so much that I was captivated by in that first viewing alone, from the boldness and sometimes expressionistic direction to the tone-setting greys of the cinematography, and a soundtrack that can switch from sinister to mournful on a heartbeat.

Deliberately reined-in though Péter Haumann's lead performance as the Inspector may be, it's still peppered with small and realistically expressed reveals and occasional bursts of anger, and in that telling interrogation scene, Gyula Pauer makes an impression as the hawker, suggesting so much without confirming anything. But the two finest performances come not from the adult cast, but the two young girls who are interrogated by K. The first is played by Mónika Varga, and there's an extraordinary naturalism to the uncertainty she displays about revealing what she knows about the man that the dead girl was secretly meeting. It never feels coached or performed, but clearly must have been for her to be able to completely ignore the presence of the film crew and a camera that was so closely locked onto her face. But it's the second girl, played by Erzsébet Nagy (though credited here as Nagy Erzsike), who proves the most arresting, never flinching or breaking eye contact with K as he questions her and caresses her face, her response being that of someone for whom this is in no way peculiar behaviour, a key aspect of why this this scene is so disturbing. Later, she is confronted by the Inspector, who also strokes her face while pressing her for information before losing his rag and bellowing at her and physically shaking her, and still Nagy doesn't break character for a second. Little to nothing is known about her, and so captivated was he by her performance that writer Stanley Schtinter – whose essay on the film graces the accompanying booklet – travelled to the region of Hungary in which the film was shot in an effort to locate her and ask her about her role. Frustrating though it must have been for Schtinter, it feels almost too perfectly in-keeping with the tone and narrative of this bold, troubling and quietly mesmerising film that despite his best efforts, he could find no trace of her.

Framed in its original aspect ratio of 1.66:1, the 1080p transfer on this region-free Blu-ray was sourced from a new 4K restoration by the Hungarian Film Institute, and it really is excellent, though you may have to watch the special features on this disc to fully appreciate just how good it is. The apparently poor quality of previous – possibly illicit – video incarnations, where the contrast was artificially boosted and huge amounts of detail were sucked into the resulting blackness, make the subtlety of this restoration all the more welcome. Twilight was shot on monochrome stock, and while the black levels are solid, they are rarely part of the intentionally greyscale palette that dominates here. This, combined with the gloomy visual pall that hangs over the film, requires a fine touch to get right – a small miscalculation in the grading and whole swathes of picture information would be invisible. Detail is crisply rendered, and those all-important close-ups of faces look terrific. Only when the psychiatrist that the Inspector consults on the case leans forward and sunlight hits his face do the highlights come close to burning out, but despite a loss of detail here, it seems clear that this was the intended look. A fine film grain is visible, and any traces of dust and damage have been soundly banished.

The Linear PCM 2.0 Hungarian mono soundtrack is also in excellent shape, with clear reproduction of dialogue and atmospherically rendered ambient sound. The music is fuller bodied than you'd expect from a mono track, and thunder and rain are vividly reproduced. Again, no traces of any former wear are evident.

Optional English subtitles are activated by default, but can be switched off either on the main menu or while the film is playing using the remote control.

INTERVIEWS

Cinematographer Miklós Gurbán (34:39)

In the first of two hugely valuable interviews shot in April of this year in Hungary with key Twilight personnel specifically for this release, cinematographerMiklós Gurbán shares some fascinating recollections of working on the film. His first meeting with director György Fehér was telling, with the reverence that Fehér commanded illustrated by the silence that fell when he walked onto the set of a film that Gurbán was then working on. He then effectively hired him on the spot, not with a contract or a formal offer of employment, but just with the words, "Come on, let's shoot." It's a command that Gurbán confirms would see him automatically turn down all other offers in order to follow whenever it was given. There's tons of interesting information in here, including on the shots already completed by Gurbán's predecessor, János Kende (which he claims they had to 'ruin' for visual continuity – still not quite sure what he means by that), the problem of matching different film stocks, his collaboration with Fehér and the technical issues of the long and sometimes complex shots, the 'greyness' of the visuals and the naturalistic lighting, and plenty more. Fascinating stuff.

Editor Mária Czeilik (30:50)

Every bit as essential is this interview with Twilight editor, Mária Czeilik, whose always interesting recollections are given more bite by her surprising frankness. This is especially evident when talking about the film's long takes, which she recalls almost nodding off when initially watching, and how tiring it became having to do so multiple times at director Fehér's insistence. "I think that those long shots are a torture for the editor and the viewer alike," she says at one point, then adding, "but if the best parts stay in, it's all good. It was very exhausting. Very." Apparently, it took her about a year and a half to get over working on this film. There's quite a bit on her first work for Fehér on the 1973 TV movie III. Richárd [Richard III], an anecdote about being coaxed into the editing room by Béla Tarr to sort out a sequence in just two hours after the assigned editor had spent all morning failing to make it work, and the news that Fehér shot a staggering 110,000 meters of film for Twilight, and that every shot in it had its own box to store the various takes in.

APPRECIATIONS

The Quay Brothers (21:29)

Probably the world's two most enigmatic and creative animators, Stephen and Timothy Quay, offer their joint opinion of the film and provide some really useful details on its production, including some specifics and analysis of its sourced soundtrack. All of the music used in the film is identified, and one of brothers (I'm sorry, but the two are identical twins and not individually identified with captions here) revealing that he discovered that the Georgian folk song used in the film was used by Kate Bush on the Hounds of Love track Hello Earth because his daughter had taught him how to use the music identification app Shazam. They recall first encountering the film on a DVD sourced from a poor quality VHS original, praise the performances of the two young girls (absolutely with them there), and suggest you might be astonished at how much patience you'll need to appreciate with they describe as a "grimly fantastic" work. In keeping with the film's look, the interview is almost drained of natural colour, sepia tinted, and given a deliberately gloomy grading.

Peter Strickland (13:51)

Berberian Sound Studio, The Duke of Burgundy and In Fabric director Peter Strickland continues the slightly meta element begun in the Quay Brothers interview (when specific reference was made to the restoration on this very Blu-ray) when reveals that he was surprised that Second Run maestro Mehelli Modi asked him to provide an introduction for a film that he previously couldn't get into. This was apparently down to the poor quality of the print that he had managed to track down, but seeing it looking as good as it does in this new restoration really did change everything. Inevitably, there is some discussion on the use of long takes, which Strickland intriguingly links to aspects of the Hungarian language, and there are some interesting insights gleaned from the film's sound recordist, József Kardos, with whom he once worked, as well as comments from the author of a new book on director György Fehér. Béla Tarr's involvement is also touched on, and Strickland admits that the film made him miss Hungary, where he used to live until being forced to move because of Brexit.

James Norton (3:37)

Filmmaker James Norton provides a brief overview of the film, touching on the importance of trees as a motif, how the heavy hand of religion and the state are symbolised, and confirming the details of the music used.

Chris Fujiwara (18:04)

Tōkyō-based author and critic Chris Fujiwara takes a deep dive into the underbelly of the film, particularly what he describes as its indeterminedness, also discussing it as a critique of power and even reality itself. He nails the element that makes the film such an intriguing puzzle when he says that it strips the source material down to a few phrases and then removes the context that we need to make sense of them, and poetically suggests that over the course of the film, "space becomes the hiding place for time."

PLUS

Trailer (2:07)

A bold stab at selling a difficult-to-market film whose most distinctive feature is one that simply cannot be captured in a two-minute sell. Inevitably, it makes it look like faster paced and more narratively straightforward than in it actually is, but it is nicely assembled and moodily atmospheric.

Booklet

A single essay here, but an arresting one by writer Stanley Schtinter, who divides his attention between an analysis of the film and the process of its making, and his journey to Hungary and his search for the elusive Erzsébet Nagy, who despite delivering an extraordinary performance in the film as the young girl that both detectives interrogate, has effectively since vanished. The main credits for the film and the special features are also included, as are some valuable on-set photographs, which are also credited.

Given that Twilight has been released on UK Blu-ray by Second Run, I'm sure I don't even have to say that it won't be for everyone, but I'll say it anyway because it really does apply here. Fans of the cinema of Béla Tarr should be able to jump straight in, as despite notable differences in the content and approach of the two filmmakers, there's a very clear kinship between them, something commented on multiple times in the special features. As I noted above, it took me a couple of viewings to start really connecting the dots and appreciating the beauty of Fehér's atmosphere-drenched minimalist approach, but even that first viewing had me hooked for a whole range of reasons that I only later was able to understand. Hearing those on the disc testify to how grim the film looked in previous, possibly unofficial incarnations made me appreciate this fine new restoration all the more, and the special features really did add to my appreciation and understanding of the film. Frankly, this is terrific disc, and for those who are game, it comes enthusiastically recommended.

|