|

Great Noises That Fill the Air is a collection of thirteen films, dealing with music and performance, from short length to the shorter end of feature-length, made for the Arts Council of Great Britain. Some of them had cinema showings while others aired on television, either on the BBC or the newly established (from 1982) Channel 4.

| |

“I don’t believe that poetry changes anything… You could write a thousand songs but that won’t bring about the revolution.” |

| |

Linton Kwesi Johnson |

Franco Rosso’s film had had a limited cinema release and was scheduled to have its television premiere on 5 April 1979 on BBC1 as part of the corporation’s Omnibus strand. But the film was postponed. The reason? With riots on the streets, it was feared that the film might influence the UK’s General Election a month later. With the election safely won by Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative Party with a majority, Dread Beat and Blood was finally broadcast on 7 June, presumably with its one use of strong language blanked out, and it attracted an audience of four million. The film also had a limited cinema release in 16mm.

Dread Beat and Blood sets the template for many of the films in this set: a portrait of the artist in question, mixing interviews (either speaking to camera or film of an interview taking place), archive footage and film of musical performance. Italian-born Rosso (1941-2016) had begun his film career as an assistant to Ken Loach on Kes and in 1973 had made a documentary The Mangrove Nine (1973), about black activists who had campaigned against police harassment. (Steve McQueen later made Mangrove, a dramatisation of the same events, as the first of his five Small Axe films.) He went on to make the feature film Babylon (1981), a dramatic film rooted in the black culture of Brixton. There’s no mistaking the intent of his and Johnson’s film, which is upfront about how black culture in Britain is marginalised and often criminalised by the police. You can see why the BBC were nervous of it, though it’s doubtful with hindsight if it might have made any difference to the election if had been broadcast when originally intended, and four decades later it’s still relevant.

STEVE REICH: A NEW MUSICAL LANGUAGE

ELIZABETH MACONCHY |

|

I’ve bracketed these two together for more than one reason – not just because they were made in the same year (1987) by the same filmmaker (Margaret Williams) but because, like Dread Beat and Blood, they epitomise a particular type of documentary. In the course of just under an hour, it aims to create a portrait of the documentary’s subject and a more-or-less chronological throughline of their lives and careers, including to-camera interviews with the subject (if alive at the time, which was the case here), their family, friends and associates, mixed with fly-on-the-wall scenes of them at work, and, given that both of them are or were composers, plenty of performance footage.

Elizabeth Maconchy was the first of the two to be made. Although Maconchy (1907-1994) had received honours – at the time of the film’s making she had a CBE and in the same year, 1987, she became Dame Elizabeth – it’s fair to say that she was a neglected figure. The film begins with a series of vox-pop interviews in which no one either knew her name or recognised any of her music. Yet she had been called one of the finest composers this country (she was born in England of Irish parents) had produced, even compared to contemporaries such as Benjamin Britten and Gustav Holst, the latter specifically encouraging her, and Ralph Vaughan Williams, who was her teacher at the Royal College of Music. It’s also undoubted that she encountered opposition for being a woman, though she was one of a network of women (including fellow composer Elizabeth Lutyens, violinist Anne Macnaghten – who is interviewed for the film – and conductor Iris Lemare) who helped each other get their works performed in London in the 1930s. Maconchy also suffered tuberculosis near the start of her career and childcare – she had two daughters – may well have had an impact on her time and creativity. She is quite open that she would not have survived without her supportive husband, and until relatively recently, her earnings as a composer were minimal.

Steve Reich, born 1936 and still with us as I write, is American, and Williams’s film benefited from funding from PBS and its New York outlet station WNET 13, and also Channel 4 in the UK. This allowed shooting in New York (interviews and performance footage) which the frequently underfunded Arts Council could not have managed on its own. Reich certainly gets to say his piece as one of the major exponents of minimalism, often using repetitive figures that slowly shift over time, an emphasis on rhythm, and moving away from the Western classical tradition, and there are plenty of examples of his work over this documentary’s running time.

This film, all of six minutes long, follows the Asian Dub Foundation on the road to Norwich for their first gig outside the city. There’s some interview material with lead rapper Deedar Zaman, but this is mostly fly-on-the-wall stuff with director Smita Malde ending with footage from the gig, often breaking out into split screen. The band’s music mixes traditional Indian sounds with ragga and reggae.

This film could be a called a miniature “city symphony”, featuring twenty-four hours in the life of Bristol and in particular its Afro-Caribbean inhabitants. There’s no other narrative. The scenes are set to music by three bands, the dub of Henry and Louis, the soul of Smith & Mighty and the jungle/drum and bass of Roni Size (a year before he was to win the Mercury Prize) and DJ Krust.

CLOCKS OF THE MIDNIGHT HOURS: THE WORK OF MAX EASTLEY

GREAT NOISES THAT FILL THE AIR |

|

Another pairing of two films from the same director/producer, this time Simon Reynell. These two short films were both made for Channel 4 with some Arts Council funding and were broadcast around midnight in half-hour slots. However, by 1988, home video recorders were ubiquitous and taped copies of the programmes circulated after the television showings, to the extent that Reynell reckons that more people watched them via this officially bootleg method than watched them on television. More recently, Reynell has set up Another Timbre, a CD label devoted to experimental music, and these two films reflect that interest, some of the releases featuring Max Eastley, who is the subject of the first film. It’s likely that such work would not be commissioned nowadays.

Eastley’s remit is to explore the characteristics and sound quality of various musical instruments and also draws on quotations from the works of Jorge Luis Borges. By 1988, NICAM stereo had arrived on UK television and if you were so enabled at the time of broadcast you could hear some unusually ambitious sound design for the time, in particular the surround-sound clock-ticks at the start.

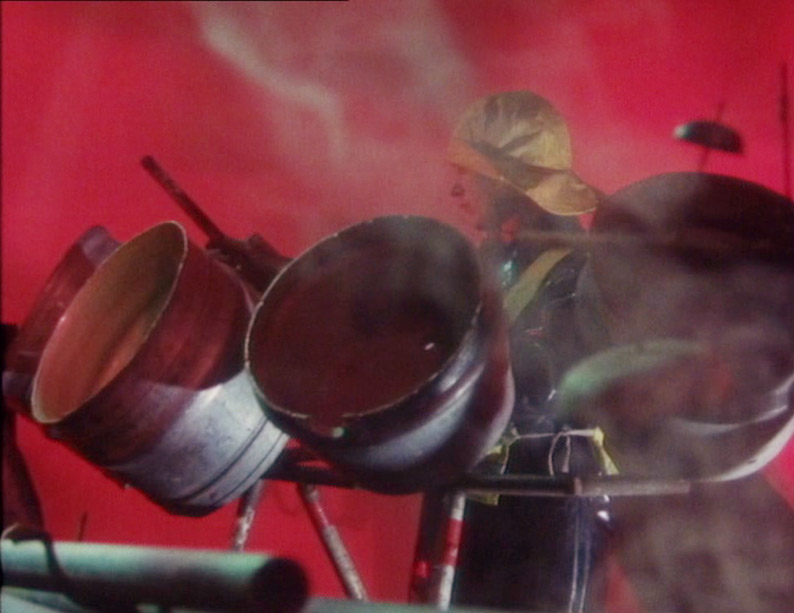

The film which gives its title to this DVD release is devoted to the Bow Gamelan Ensemble, who were formed in London in 1983. Percussion, often with instruments made from scrap metal, is to the fore here and they have often used outdoor architecture – for example, the empty concrete barges at Rainham Marshes on the Thames for their potential for resonance.

| TEN YEARS IN AN OPEN NECKED SHIRT |

|

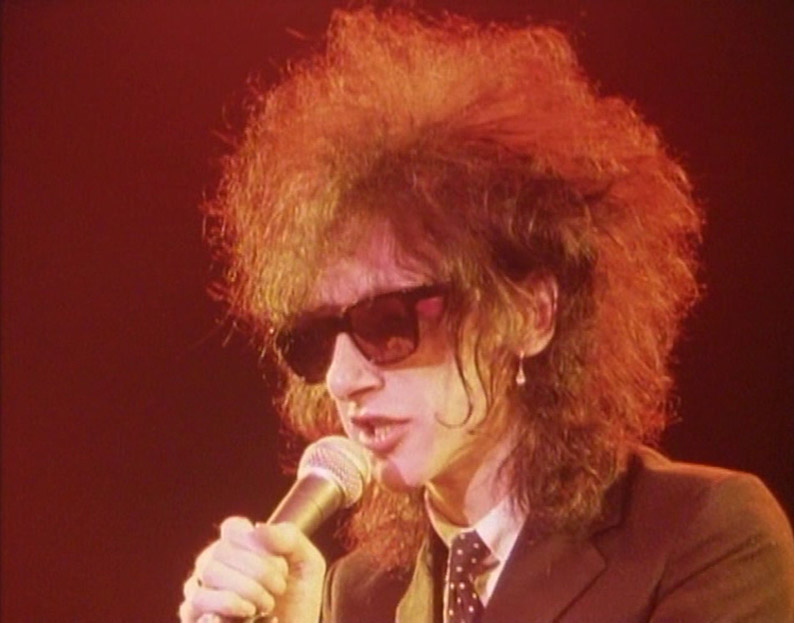

Disc Two begins with the longest film in the set, though still only an hour long. Nick May’s portrait of John Cooper Clarke follows the pattern of others in the set. There are interviews, and the camera is sometimes a witness to Clarke being interviewed, for radio in one case, and a three-way discussion between Jules Deelder, Michèle Roberts and Clarke. There is also live footage, so plenty of Clarke’s punk poetry, with appearances from Linton Kwesi Johnson (with whom Clarke was on tour at the time the film was made) and Seething Wells. All familiar tactics, but co-writer/director Nick May also throws in short dramatised scenes, so Hilary Mason shows up as a frightening nun.

May was conscious that this might have been the last chance to capture Clarke on film in his prime. The glasses were because Clarke’s vision was very poor and he was also agoraphobic, and later in life became a heroin user. The film was made for cinema release as well as television showings (Channel 4 again) so there’s a sense that some of the material is toned down even for a channel which had been notoriously sweary in its early days: it’s “bloody” in “Evidently Chickentown”, not the stronger variant you may be familiar with. That said, there was no General Election impending, so no objection to the political content, and Johnson gets to perform a poem about the sus laws. Clarke’s poems are performed at full length, not as extracts, which was his condition for taking part in the film.

This short piece is entirely performance, a mixture of performance poetry from Martin Glynn, dance by Sandra Golding and percussion from Steff (Steve Clare). It shows how the African oral tradition plays into more recent musical forms such as rap.

| CORNELIUS CARDEW 1936-1981 |

|

Cardew was in his short life one of Britain’s leading avant-garde composers and likely a prophet without much honour in his own country. After his death, memorial concerts of his work were performed in many countries, less of them in this one. Cardew began as an assistant to Karlheinz Stockhausen in the late 1950s, and in fact Stockhausen is one of the interviewees who pays tribute in this film. Cardew often abandoned conventional scoring to devise a system which was in part open to interpretation by the musician, and we see one of his “scores”, an elaborate diagram which Cardew worked on in during his then day job as a technical draughtsman. Despite some elements of chance in his work, Cardew most usually composed for conventional instruments and human voices, and we see plenty of extracts. One such is “Mountains”, a technically demanding work for solo bass clarinet.

By the 1970s Cardew was an active member of the Communist Party and repudiated his earlier work and the musical avant-garde in general, perhaps conscious that he could be accused of elitism in producing music which rightly or wrongly had a narrow appeal. Much of his output of the last decade of his life was given over to writing revolutionary songs. He died in 1981 as the victim of a hit-and-run. There are suggestions that his death was a politically-motivated assassination rather than an accident.

Philippe Regniez’s film follows the conventional form of several of the films in this set, with the proviso that its subject was no longer alive when the film was made. Cardew appears in archive footage but none of this is interviews. As with many such documentaries, it may not tell you much you didn’t already know if you were familiar with Cardew’s life and work, so its value is mainly for beginners, of which I was one.

This short film begins with Steel ’n’ Skin’s founder Peter Blackman talking to camera about how people from different nations in Africa and the Caribbean come to Britain and how their different cultures blend. Steel ’n’ Skin is a collective from Merseyside whose workshops in the community involve the making of musical instruments, traditional clothes and prints, cookery and hair-plaiting as well as musical performances.

We now go to Trinidad and Tobago, and Karen Martinez’s documentary introduces us to “chutney soca”, a blend of the music of the two primary ethnicities of the nation: Indian (hence the chutney) and African (soca, or calypso). It’s often performed by women, giving them a voice in popular music, with performers like Drupatee Ramgoonai defying social pressures to stay at home rather than on a carnival stage.

| MUSIC IN PROGRESS: MIKE WESTBROOK – JAZZ COMPOSER |

|

Westbrook (born 1936 and still with us of this writing) was a key figure in the development of British jazz, beginning in the late 1950s and by the early 1960s based in London and leading a regular band at Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club. He played more modern and avant-garde jazz than many of his more “trad” contemporaries, such as Acker Bilk and Kenny Ball.

Despite its relative length, Charles Mapleston’s film mostly depends on performance, with Westbrook, on piano and euphonium, leading a six-piece band which also features his wife Kate on tenor horn, piccolo and vocals. (It should be said that the film’s credits don’t specify who plays which instruments, nor the instruments played by other musicians who appear, so full marks to the DVD booklet for including this information.) Among the works featured are an arrangement of Brecht and Weill’s “Kanonen Song” from The Threepenny Opera. Mike Westbrook does say some things to camera, coming over as modest, but if you didn’t know much about his work and his place in musical history, you wouldn’t know much more forty-three minutes later.

The BFI’s release Great Noises That Fill the Air is a two-disc DVD set, both discs encoded for all regions. The package gains its 12 certificate because of Dread Beat and Blood (which had a AA certificate on its original cinema release). The other films do not appear to have been submitted to the BBFC, as being exempt by being documentaries. Almost all of them have nothing that would exceed the bounds of a U certificate, let alone a PG, though Ten Years in an Open Necked Shirt would also get a 12 for occasional strong language.

The aspect ratios are in every case 1.33:1. Dread Beat and Blood was remastered in 2K resolution from the 16mm negative, but the transfer notes in the booklet are not forthcoming on the sources for the other films, only saying that they are from “the best available materials”. Many of the films were shot on 16mm, though in some cases the transfers come from tape sources. For example, a small square graphic appears in the top right corner of the frame in Steve Reich so as to signal that a commercial break is forthcoming.

The soundtracks are in all cases Dolby Digital 2.0, which plays in surround or mono, depending on the film. For the record, the following are mono: Great Noises That Fill the Air, Ten Years in an Open Necked Shirt, Cornelius Cardew, Steel ’n’ Skin, Music in Progress. In most cases, the stereo tracks are most likely due to their TV broadcasts at a time when UK channels were broadcasting in NICAM stereo. (I doubt that Dread Beat and Blood played in any other format than mono in 1979, though.) In most cases, the music is the thing, and it comes through well with the proviso that as this is a twenty-five frames per second DVD and some of these films were shot at 24fps for cinema showings, some of it may be speeded up half a semitone. However, I don’t have absolute pitch to verify this. There’s no LFE channel, but by subwoofer did pick up some redirected bass, a good example being the opening low notes of Bristol Vibes.

Regrettably there are no subtitles for the hard of hearing available.

There are no extras on the discs themselves, but the first pressing of this release includes a thirty-two-page booklet. This begins with an overview, “Arts Council: Taking Risks” by Rodney Wilson, who worked for the Arts Council between 1970 and 1998 and was executive producer on many of the films in this set. Before 1978 the Council was mainly involved with visual arts, but a new remit included music, poetry and performance and also allowed for co-productions making some of these films possible. This is followed by credits for and notes on each film, often by someone involved in their making: respectively Linton Kwesi Johnson, Rod Stoneman, Frances Morgan, Smita Malde, Ruppert Gabriel, Simon Reynell on both of his films, Anne Bean (on Great Noises That Fill the Air), Nick May, Pauline Bailey, Frances Morgan again, Steve Shaw and Kaleem Aftab separately on Steel ’n’ Skin, Karen Martinez and Jonny Trunk. In between these is a two-page biography of Cornelius Cardew by Luke Fowler, which fills in details that the film doesn’t include. Finally, Rod Stoneman (who was a deputy commissioning editor for Channel 4) talks about how the channel was a home for work like this, often radical and experimental and quite unlike what had been broadcast before...and since, as Channel 4 is a very different channel today.

Great Noises That Fill the Air is inevitably a mixed bag, as with any musical- or performance-based work, personal taste will be a factor in your appreciation or otherwise. But even so, this set is a useful introduction to many types of music you may have been unfamiliar with.

|