|

I'm not sure I actually have the necessary literary skills required to describe the opening nine minutes of Vera Chytilová's 1970 Fruit of Paradise [Ovoce stromu rajských jíme] in any detail. After watching it, I was left with the feeling that to accurately capture not only what unfolds, how it unfolds and the effect it has on a willing viewer would require the invention of a whole new set of descriptive nouns and adjectives. If you want the simple version, try this: imagine, if you can, the story of Adam and Eve told as a hyperactive and psychedelic LSD trip whose imagery is infused with a myriad of organic textures. Whatever you come up with, the likelihood is that you're not even close. And it is, quite simply, amazing.

The switch to what you might more readily call live action is signalled when an apple falls into the hand of the carefree Eva, a contemporary descendent of that fabled first woman. The connection is implicit, signalled by the symbolic fruit from which she takes an almost sensual bite and the small snake that she discovers wound around her hand. Soon a serpent in human form will be tempting her with different vices.

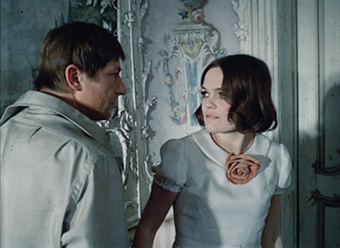

The modern Eden in which she and her husband Josef are happily idling is a new age health retreat, a country house physically distanced from the real world and surrounded by fertile woodland and located close to a steep and featureless sand dune, on which the guests relax and cheerfully frolic. When out gathering herbs one day, Eva chances upon (and is nearly showered by urine from) the bearded and politely charming Robert. He is dressed in red, which is clearly intended to have either political or biblical overtones, or perhaps a bit of both. When Eva discovers a small red briefcase hidden in a tree, she asks Robert if it is his, but when he attempts to take it from her she is curiously reluctant to let it go. Its contents are a mystery and are likely of little importance, but the case itself appears to be symbolically significant, a physical representation of closely guarded secrets that Robert then buries and Eva later uncovers. What is Robert hiding?

Eva is drawn to Robert and becomes jealous when he targets his intentions at other women. Josef in turn is initially angered by Eva's infatuation with this stranger, despite early hints that he has had his share of past peccadilloes and the fact that when playing with other guests he chases after everything in a bikini. When he first confronts Robert, his hostility is very much that of the outraged husband, but in seemingly no time the pair have settled their differences and Josef is actively encouraging Eva to spend time with her new friend. But just who is he? When prompted to read aloud a newspaper article on women who have been murdered, is he sharing the concern of his audience or slyly boasting of his nefarious achievements? The film itself soon sides towards the latter, when Eva explores an attic room and expresses herself entirely through passionate percussion, an action whose apparent metaphorical nature is humorously undercut when Josef enters and angrily demands barks, "Don't pretend to be drumming!" Shortly before this interruption, Robert is seen sneaking up behind Eva, holding his tie before him like an open garrotte. Moments later, he spies Eva lying in the grass below and engineers for a statue to topple in her direction. That the statue is of an angel and cast in the purest white feels very much part of the film's consistently active biblical substructure.

Narrative development repeatedly plays second fiddle to director and co-writer Chytilová's extraordinary experimentation with film form and traditional notions of cinematic storytelling. The plot moves along in disjointed hops, and intermittently the filmmaking itself adopts a subjective and even expressionist viewpoint, employing a range of experimental techniques – small jittery jump-cuts, reversed and accelerated motion, ultra-wide camera angles, multiple exposures and dizzying montages – to not just observe Eva but to create a vivid sense of her emotional state. Thus, the sort of frantically speeded-up and blurred imagery that James Wan was later to put to more superficially eye-catching use in Saw is here employed to visually express Eva's sense of overpowering frustration. Not only was Chytilová pioneering these techniques, she was using them with purpose.

The film is consistently arresting in its visual experimentation (let's give a shout for Jaroslav Kucera's cinematography and Miroslav Hájek no-holds-barred editing), but as an audio-visual experience it's intermittently mind-blowing. It's genuinely impossible to imagine the film working anywhere near as effectively without Zdenek Liska's astonishing musical score, which is melded to the visuals as completely as the hypnotic Philip Glass score for Godfrey Reggio's Koyaanisqatsi and is even more varied and adventurous in its scope. More than once I found myself pondering on the riddle of which came first, the imagery or the music, as the two are so organically bonded that each feels specifically crafted to compliment the other. It's worth noting that the insanely prolific Liska – this was one of eight features he scored in 1970 alone – also wrote the music for Juraj Herz's superb The Cremator and a number of early Jan Švankmajer shorts.

The themes explored by Fruit of Paradise – temptation, loss of purity, the corruption of innocence – should be evident to all but the most disinterested viewer, but are explored in such an artistically adventurous manner that there are times here when they play like virgin cinematic ground. It's the also boldness of Chytilová's approach that ensures that the symbolic use of white and red – and the climactic transition from one to the other – never feels as obvious as a written description would doubtless make it sound. Second Run regulars should already be aware of Chytilová's work through her superb 1966 Daisies. If you're a fan of that film (as surely you must be), then you should consider Fruit of Paradise essential viewing.

Presented in its original 1.37:1 aspect ratio, the DVD transfer here has been sourced from a new high-definition digital transfer prepared by the Czech National Archive, and is making its UK premiere on any format here. For the most part it looks impressive, with a crispness and level of detail that is first rate for an SD transfer, plus a generally punchy but not overly aggressive contrast range and a vibrant reproduction of the brighter colours. There are a fair few dust spots remaining and the odd small, frame-long snippet of damage, which does become more prominent on some of the reel changes. In all other respects, a typically fine Second Run transfer.

The Dolby 2.0 mono track is clearer and brighter than it has any right to be given the film's age, though unsurprisingly there's little going on at the bass end of the scale (that said, some of the drums Eva hits have more kick than expected). The music score comes across particularly well, which is how it should be, though taking its cue from the picture there is audible crackle on some of the reel changes.

Short film – Ceiling (41:04)

Ceiling [Strop] was director Vera Chytilová's Prague Film and TV School of Academy of Performing Arts graduation film. It paints a compelling and increasingly sobering portrait of Martha, a medical student who works part-time as a fashion model, a sideline career at which she has found some success but that appears to be slowly draining her of her humanity. Shot in gritty monochrome, the influence of both French and Czech New Wave cinema is clearly evident and put to effective use, resulting in a work of almost documentary objectivity that most effectively gets inside of its subject's head. The sense that Martha is very much alone in spite of her personal and professional relationships is clearly communicated, while the men in her life come across as a self-interested, shallow and exploitative bunch. The 41 minute running time allows Chytilová time to explore these aspects of Martha's life at an unforced pace, which brings the message home without ever feeling didactic. It's a hell of a graduation film, and one whose playful opening credits are more inventively executed than some of this year's mainstream movies have been in their entirety.

Booklet

The centrepiece of this booklet is a detailed and informative essay on Vĕra Chytilová and Fruit of Paradise by Peter Hames, which I deliberately avoided reading until after I'd finished my own, somewhat more humble piece. He's also delivers a few useful paragraphs on Ceiling. Credits for the film are included.

Fruit of Paradise is exactly the sort of film that gets me excited about a specific filmmaker and their body of work, and yet in the sort of story we hear a little too often when discussing bold Eastern European cinema from years past, the film apparently led to Chytilová being condemned by the authorities for making 'vehicles of nihilism' (that's a phrase I'd want on the poster) and banned from directing films for several years. It's a tad sad that UK viewers get to finally see this film almost exactly a year after its bold and talented director passed away, but that we are able to see it at all is something to be celebrated. The film itself will doubtless annoy the hell out of some, but for the rest of us this disc, blessed as it is with two excellent extra features, comes highly recommended.

|