|

While

the debate continues over whether live action feature films

can really be classified as art, the case is and always

has been a lot easier to make for animation. The animated

short in particular is often a labour of love for its creator

and free of the commercial pressures that most features are saddled with and that so many filmmakers find themselves battling against.

Such films can and often do exist as expressions of the animator's

artistic vision, and their pleasures relate less to character

and narrative than the design and animation itself. Like

painting or sculpture, an animated short can be admired

and enjoyed for its composition and for its technique and

can provoke an emotional response purely on the basis of

its artistic qualities.

What

works for ten minutes, however, cannot not necessarily be stretched

to feature length, and the animated feature, although still

easy to appreciate for its design and technique, generally requires

a storyline on which the art can be hung. Animated features require

a considerable amount of time, effort and money to produce, and those who fund

them expect to see a return on their investment. Be artistic,

sure, but at least tell a story that will get people into

the cinema to see it. Which in some ways brings us full circle – given these commercial constraints, can an animated feature

really be categorised as art? I am here to assure that it

can. You want proof? It's right here, on this DVD, in pretty

much every frame of René Laloux's extraordinary film.

If

you've never heard of Fantastic Planet

(La Planète sauvage – literally 'The

Savage Planet'), it's hardly surprising. Made in 1973,

it did the rounds of UK art-house cinemas in the years that

followed, sometimes teamed up with a second, more commercial

feature to get the punters through the door. I first saw it back

in 1980 on a double bill with Ridley Scott's Alien,

of all things. Don't get me wrong, I adore Alien,

but this was still a peculiar pairing, and many of those drawn

to Scott's sf/horror masterpiece would be unlikely to sit

still for Laloux's equally distinctive but stylistically

very different vision. Since then, the film has sunk into

virtual obscurity, at least in the UK (it has apparently

found a small but devoted late night audience in the USA),

and news that Masters of Cinema were to revive it for UK

DVD release had me bopping about with glee. That first viewing

had made a serious impression, but a lot of time had passed

since then. Twenty-six years and a LOT of films later, would it

still look so remarkable, so innovative?

Oh

yes.

La

Planète Sauvage is, as the title suggests,

a science fiction story, but one unusually strong on the suggestively

subtextual. On the planet of Ygam, the diminutive, human-like

Oms lead an uncomfortable co-existence with the giant, blue-skinned

Draags. The Draags regard the Oms largely as vermin, but

some of the Draag children keep them as playthings, holding

them captive with collars that can be used to physically recall their wearers by remote

control. The focus of the story is Terr, a baby Om

whose mother is killed and who is rescued and domesticated

by a young Draag named Tiwa. As Tiwa grows, her schooling

is undertaken through a telepathic headset through which

she absorbs knowledge, but unbeknown to her, Terr is able

simultaneously receive the information. Eventually, Terr

escapes, taking the headset with him, and joins a colony

of Oms who live in an big tree in a park. Armed with the

headset, they set about improving their own knowledge, while

the Draags continue their periodic process of Om extermination.

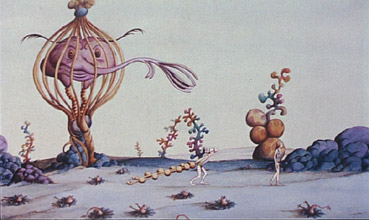

Although

you'll find the dual species/master-slave/oppressor-rebellion

story throughout science fiction literature and even film

(Planet of the Apes anyone?), it remains

a potent one because of its metaphoric meat in a world that

seems incapable of learning from history. But if the story seems

familiar then the handling is anything but. Working with graphic artist Roland Topor, composer

Alain Goraguer and sound effects deviser Jean Guérin,

Laloux creates an alien world like nothing you'll have seen

or heard, a consistently extraordinary multimedia artwork

in which sound, art design and movement are exquisitely

combined into a vividly surrealistic whole. The occasionally

recognisable touchstones are there – Bebe and Louis Barron's

electric tonalities for Forbidden Planet,

the playful cut-out surrealism of early Terry Gilliam animations – but the vision here is so complete that they feel more coincidental

than in any way borrowed or adapted.

Although

principally compelling for its technique – every few seconds

there is something to widen the eyes or drop the jaw – the

story still makes for fascinating reading and interpretation.

The death of Terr's mother, for example, is the result not

of calculated nastiness but the thoughtless game-playing

of the Draag children, offering a reading that questions our attitude

to all forms of wildlife, domesticated or otherwise. This is carried through in the treatment of Terr as

Tiwa's pet, dressed in a variety of absurd costumes for

its owner's amusement and held captive with a collar that

can return him to his owner at the flick of a lever.

The descriptions of Oms as vermin, the complaints about

the speed at which they reproduce and the later extermination programme can't help but recall Australia's problems

with wild rabbits and their attempts to control and ultimately

wipe them out in the 1950s. But in making both species humanoid

in form, Laloux inevitably invites an interpretation that

has the Draags as an army of occupation and the oppressed

Oms as their victims. Abused, domesticated and ultimately

gassed in coldly systematic attempt at genocide, the picture

is completed when the Oms learn to organise and fight back

against their oppressors. It has been suggested that the

film was a response to the 1966 Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia,

but the genocidal overtones more readily recall the horrors

of Nazi Germany.

But

this remains a subtextual element of a feature that

is rightly celebrated for its achievements as film art.

In that respect it remains a triumphant one-off, a very

special work that vividly demonstrates the imaginative possibilities

of a medium in which the imagination of the filmmakers,

unconstrained by the cost of large sets or complex make-up

and creature modelling, is truly able to run free. The animation

can sometimes feel a little crude by today's standards,

but Fantastic Planet is nonetheless a film

to see and to hear and to treasure, then tremble in horror at the prospect of the threatened US live

action remake.

Framed

1.66:1 and anamorphically enhanced, this is not quite the

transfer I had hoped for, the fault largely of a source

print that is in less than pristine condition, with dust

spots and film grain visible throughout, sometimes markedly so. In other respects, the transfer is sound enough,

with contrast and colour about right and the detail good,

but a still few notches short of great. Potential viewers

should note that this is an NTSC disc, which will present

no problems on most modern TVs and avoids any conversion

issues from what was presumably an NTSC digital original,

but there may still be a few out there for whom this could

be an issue.

There

are two Dolby 2.0 mono soundtracks available, the original

French and the first release US dub. In some ways they sonically

show their age, not having the dynamic range of more recent

films, but are clean enough nonetheless – certainly the

music and sound effects come over well. Although the original

French track is preferable and better voiced, the US dub

is not at all bad, though small but occasionally significant

changes have been made to the dialogue. The US track is

slightly louder than the French.

The

optional English subtitles are clear and, as far as my limited

French can tell, accurately translated.

Although

not exactly feature packed, the inclusion of two of René

Laloux's short films, one made before and one several years

after the main feature, is a very big plus.

Les

Escargots (10:43) was made in 1965 and marked an

earlier collaboration with Roland Topor and Alain Goraguer,

whose contributions were so crucial to the distinctive style

of La Planète sauvage. A surrealistic

tale of a farmer whose failing crop is revived by his own

tears, then is destroyed by giant snails that subsequently

go on the rampage, it inevitably shines in its artwork but

is also very funny in places, not least the farmer's methods

of inducing a constant stream of tears, which include reading

Shakespearean tragedies and a back-mounted machine for bashing

himself repeatedly on the head. The quality of the transfer is not bad, given

the age and probable rarity of prints.

The second film, the 1987 Comment Wang-fo fut sauvé [How Wang-fo Was Saved] (14:55), was inspired

by an old Chinese folk tale and based on the drawings of

Philippe Caza. This is a beautifully drawn and animated

piece that Laloux believed may have been his finest work,

and is nicely transferred from a very good quality

original.

An

unusual but welcome extra is the music soundtrack,

25 tracks covering virtually the entire main feature and reproduced

at pleasing quality. As a DVD extra it won't be easy to

transfer to your iPod, but fascinating though it is, this

is hardly exercise music.

Finally there is the usual MoC booklet

which runs for 40 pages and contains an interesting essay

on Laloux and his collaborators by Craig Keller in type

large enough for me not to need my glasses to read, plus

some attractive stills, photographs and artwork.

A

still unique film experience is given good if not exemplary treatment by Masters of Cinema. It's a shame

that a pristine print could not be found, but the disc still

scores serious points for the inclusion of the two Laloux

shorts and what is effectively the soundtrack album. If

you can make allowances for the source print, and Masters

of Cinema's track record suggests that this is probably

as good as you'll find for now, then for the films and the

score the disc comes recommended.

|