| |

"When I came back to Germany and I tried to hold all the investors together, they said to me 'How can you continue? Do you have the strength or the will or the enthusiasm?' and I said 'How can you ask this question? If I abandon this project I would be a man without dreams. And I don't want to live like that.'" |

| |

Werner

Herzog |

Just

how many 'making of' documentaries get their own DVD

release? The one that springs most readily to mind is

Keith Fulton and Louis Pepe's Lost

in La Mancha, but this has to be considered

a special case, only growing into a feature after the

film whose production it was commissioned to document – Terry Gilliam's The Man Who Shot Don Quixote – collapsed

following a string of project-crippling disasters. So what does

that leave? OK, let me restate that original question

for DVD aficionados: How many making-of documentaries

get a stand-alone DVD release from US home video supremos Criterion? Yeah, Burden of Dreams is regarded that highly.

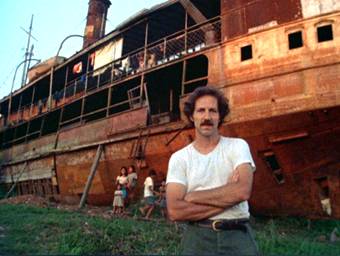

Werner Herzog's 1982 Fitzcarraldo is a film about obsession made by one of cinema's most

notorious obsessives. It was also a work that, like Gilliam's

above-mention and as-yet still unfulfilled project, ran into a spectacular series of production

problems, most of which were (often wrongly) attributed

to Herzog's single-mindedness and complete disregard

for the comfort and safety of his actors and crew. Much

of this hit the news stands while the film was in production,

prompting Herzog and his producers to ban all press

from visiting the location, which only served to feed

the negative stories about just what was going on deep

in the Amazonian jungle. The only people documenting

the shoot were ex-Berkeley graduates Les Blank and Maureen

Gosling, who had been invited in by Herzog following

his starring role in their unambiguously titled short film Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe (see the extras

below). They first joined the project late in the pre-production

for two weeks in October 1979, then returned in April 1981,

by when the film had already hit one potentially production-busting

problem, and ended up staying for two-and-a-half months. By the

time they left, Blank had become weary of the whole

experience and just wanted to get home.

Despite

the differing outcomes of the productions being documented, the similarities with Lost

in la Mancha are noteworthy, as despite Herzog's

eventual success, the film cannot help but highlight the problems with the production rather than its successes (something emphasised

by the dourly delivered narration), and it's certainly that aspect that made the biggest impression when I first saw the film back in the mid-80s.

Indeed, the memory distortion caused by the passing

of time had me convinced that the shoot was far more

problematic than it clearly was, though since then

I have also seen Hearts of Darkness (another eye-opening record of film-makers, obsession

and the jungle) and My Best Fiend,

Herzog's portrait of his friend and collaborator Klaus

Kinski. The second of those films in particular threw me off, containing

as it does an extract from Burden of Dreams showing

Kinski screaming blue murder at production manager Walter

Saxer, a scene that was not actually included in the film (again, see the extras below). By comparison, the

moments of confrontation that have been included are a lot more sedate,

and some of the most alarming incidents are related

through voice-over and interview rather than shown on screen.

As

a portrait of an obsessive perfectionist, Burden

of Dreams is consistently fascinating, and

though some have seen it as evidence of Herzog's legendary semi-lunacy, for this young ex-film student who sat open-mouthed

on that first viewing, Herzog came across as a man completely

and utterly dedicated to his vision, to the extent that he seeming willing to lay his

life on the line to realise it. I didn't appreciate it

at the time (how could I?), but he was everything I wished I was but

would ultimately never be. Of course, he had also made the staggeringly beautiful Aguirre, The Wrath of God. In my early twenties I firmly believed that Werner Herzog

was a filmmaking God.

Burden of Dreams unfolds as a study of ambition at war with a combination of circumstance,

an alien environment and even simple logic, and

in that respect is as compelling and incident-filled

as the aforementioned Hearts of Darkness and Lost in la Mancha. Without doubt

Herzog's biggest set-back occurred between Blank and

Gosling's two visits – and was thus not captured on film –

with the departure of lead players Jason Robards (illness) and Mick

Jagger (musical obligations)

after forty percent of the film had already been shot.

This meant recasting and starting again from scratch,

something that would have frankly floored most productions at this stage.

On top of that, Herzog was having to deal with an

increasingly hostile indigenous population and outrageously

false stories appearing in the press suggesting he was

running drugs and guns and destroying local farmland.

Eventually the film crew were driven out and their sets

and living quarters burned, forcing a relocation that

took them even deeper into the jungle than originally intended. Even

then Herzog was faced with the task of hauling a gigantic

steamboat over a mountain, something he insisted on doing for

real, in spite of the protestations and eventual resignation

of his Brazilian engineer and the seemingly impossible nature of the task. At this point in the production,

Herzog and Fitzcarraldo had become virtually indistinguishable

from each other, both faced with the same almost impossible

physical challenge in order to realise their respective

dreams.

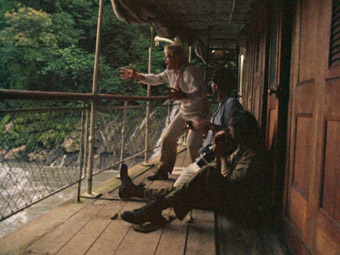

Even

this, though, pales in comparison to the decision to

take the giant boat into rapids with the cast and

crew on board – as the boat collides repeatedly with

the rocks, cameraman Thomas Mauch is injured and even

Blank quits shooting in order to protect himself from

harm, creating a very real sense that Herzog's obsession

has disabled his sense of self-preservation. And yet,

by God, I wanted to be on that boat, to share the danger

in order to get footage that just no-one else would

dare to pursue. I was not at all surprised when I read

in Blank's own diaries that Herzog, Kinski and Mauch

were positively jubilant after this river trip, overcome

by the adrenaline rush of having diced with death and

survived, and knowing that they had created

something special in the process. Looking back from an age in

which spectacle is largely created on computers, the

foolhardy daring of this decision, coupled with its reckless

sense of adventure, is something to be treasured.

More

than just a record of the technical aspects and difficulties

of the Fitzcarraldo shoot, Burden

of Dreams has an ethnological element,

with the lives and even conflicts of the local tribespeople made very much part of the story. Although the

most serious incidents happen off-screen, their gravity

is nonetheless sometimes effectively communicated –

the news that a couple have been hurt in an attack

by a rival tribe is horrifically illustrated when we

are shown their injuries (which are successfully treated by the

camp's doctor) and the arrows used to inflict the wounds,

which are closer in size to what we would think of as

spears. As

the problems pile up, even Herzog shows signs of losing

heart, cursing the jungle and nature itself as obscene

in a powerful monologue laced with frustration and bitterness.

By now, though, the director has invested too much time,

energy and blood to give up, and had by then promised

that he would either finish the film or walk off into

the jungle and never return, a statement those around

him knew was sincerely made.

The

film's many strengths are retrospectively tempered to

a small degree by the additional information supplied

by the commentary and accompanying diaries and the knowledge

of what was not captured on film. Chance certainly

plays its hand here, but so does Blank's own decision

to switch the camera off at moments when others may

have kept on rolling, and Herzog himself maintains that

the film documents only a small part of the shoot and

that many key events were not caught on camera.

Blank's decision to leave the production before its completion

is understandable once you read the diaries, but it does rob

the film of Herzog's most triumphant success, when the

boat finally reached the top of the mountain. Extracts

from Fitzcarraldo are a compromise

stand-in, lacking as they do the reactions of those involved that the scene cries out for.

But

although this post-production analysis can create a

slight sense of incompletion, this has to be put into

perspective. The coverage may be greater in Lost

in La Mancha, but it is important

to remember the sheer speed with which Gilliam's film

fell apart, grinding to a halt in a matter of days, whereas

the shoot on Fitzcarraldo took several months,

and film-worthy incidents were

few and far between. That Blank and Gosling were not

there for the whole shoot is certainly a shame, but some non-chronological

editing still gives the story a suitably memorable climax

in the shape of the aforementioned hair-raising trip through the rapids,

an incident that actually occurred early in the shoot

(as evidenced by earlier shots of Thomas Mauch with

dressed wounds that he has yet to receive), but in dramatic

terms so difficult to top that its relocation feels

right.

Even

in retrospect, Burden of Dreams is

a consistently fascinating look behind the scenes of

a troubled but hugely ambitious production, providing

a window into the tortured difficulties that sometimes

go hand-in-hand with creating great cinema, and giving

us a rare glimpse of one of cinema's true mavericks

at work. Its high reputation is fully deserved,

but the film has too often been used as a stick with which

to beat both Herzog and Fitzcarraldo itself, the common cry being that the making-of documentary

is actually superior to the work whose construction

it is recording. As far as I'm concerned this is complete nonsense, as despite

being unfavourably compared to Herzog's similarly located Aguirre, the Wrath of God (and come

on, that was a work of cinematic genius, so

what chance has Herzog got there?), Fitzcarraldo is still marvellous cinema, and the passing of time has

done nothing to convince me otherwise, despite Nelson

Muntz's protestation in The Simpsons that

"The movie was flawed!" Championing a less

widely seen or distributed film as a way of taking a

poke at one that has achieved more widespread fame has

been a weary critical sport for some time, and though it

is sometimes justified, too often it is little more

than a lazy short-cut to critical hipness.* Fitzcarraldo is, in Blank's own words, "an amazing film,"

and both it and Burden of Dreams deserve

to sit side-by-side on anyone's DVD shelf.

Given

that the film was shot on 16mm negative stock (and what

looks like high speed stock at that) in often less than

ideal conditions, grain is inevitable and you certainly

get it. Colours are generally

faithful, though lean towards green due to the dominance

of the landscape and the lack of strong colours in most

shots. Contrast and black levels are fine, and the overall

look will hold no surprises for anyone familiar with

post-vérité low-budget documentary works.

Dust spots and print damage are very rare – the print

has been very effectively cleaned up for this release.

The picture is in its correct 1.33:1 aspect ratio.

The

sound is Dolby Digital 1.0 mono and is clean and distortion

free, if restricted in is dynamic range.

Though

at first glance not one of Criterion's feature-laden

releases, there are a fair number of very good extras

on offer here.

Les

Blank's 1980 short Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe (20:15), one of the films that helped land him the job

of shooting Burden of Dreams, is included

in its entirety. The result of a bet made with the then

fledgling film-maker Errol Morris (Herzog said that if

Morris ever made a feature then he would eat his shoe

– Morris made Gates of Heaven, and of course later went on to become one of the most celebrated of modern American documentarians), the

film is a light-hearted but revealing and engaging portrait

of the maverick director, who states that we should declare

open war on TV commercials (I told you he was a God) and

suggests that cooking and walking are the only viable

alternatives to film-making. Both are demonstrated on

camera, the former proving the funniest as Herzog carefully

prepares the ingredients that he will cook with the shoe

to at least give it flavour. The title event itself has

a sense of spectacle, as Herzog climbs on stage, compares

his cooked shoes to Kentucky Fried Chicken and hopes his

actions will serve as an encouragement to anyone who wants

to make a film but "doesn't have the guts,"

encouraging his audience to do whatever they have to in

order to make their films, including stealing equipment

and stock. He also recalls the time on Even

Dwarfs Started Small when he fulfilled a promise

by throwing himself into cactus, an act that he still carries the scars from.

Dreams

and Burdens (38:00) is a substantial four-part interview with

Herzog conducted in 2005, in which he looks back at the

making of Fitzcarraldo, both as he

remembers it and how it comes across in Burden

of Dreams. He talks about the casting, his relationship

with Kinski, Les Blank's films, the reasons for actually

pulling a ship over a mountain, the safety issues surrounding

it, and that trip through the rapids. He also addresses

what he believes are the strengths and weaknesses of Burden

of Dreams, which he describes as recording just

a small segment of the production and criticises for omitting

important information, but also calls it the only 'making-of'

film that is not "embarrassing." This is presented

in anamorphic 16:9.

Criterion

have usefully included a commentary track by director Les Blank and editor and sound recordist Maureen

Gosling, with Fitzcarraldo director Werner

Herzog recorded separately and edited in when appropriate.

Herzog himself notes the oddity of him commenting on a

film that is effectively a comment on him and his work,

but contributes some useful information regarding the

location and people, and his reaction to Blank and Gosling's

film, which he admires but at times wishes had never

been made. He also points out, as mentioned above, that

the film does not provide a full picture of the shoot

because Blank and Gosling simply were not present for

many key events, and claims that Blank missed some key events simply

because he overslept. He also talks about

the content of his "obscenity of nature" monologue,

making reference to what he calls the "Disneyfication

of nature" and labeling the manic Kinski as a tree-hugger.

Blank and Gosling (mainly Blank, it has to be said) provide

a useful background to the making of the film, expanding

on its ethnographical elements and confirming that many

of the natives did finally gain legal ownership of their

land and that Herzog was instrumental in making this

happen. How fresh the information seems will depend largely

on whether you listen to the commentary first or read

Blank and Gosling's diaries, as there is some overlap

here.

Two deleted scenes (5:52)

show completely opposite sides of leading man Klaus Kinski

and are presented 16:9 anamorphic as extracts from Herzog's

documentary on Kinski, My Best Fiend,

in which they were used. The aforementioned (and fascinating)

Kinski rant is counterbalanced by a quite magical sequence

in which the actor, in a state of cheerful serenity, performs

a gentle hand dance with a friendly butterfly.

The trailer (1:28) is presented

4:3, is in good shape, has the same downbeat voice-over

as the main feature and includes a few shots not in the

film itself. The '40 minutes longer' caption makes reference to

the hour-long cut-down version delivered for PBS television,

who put up some of the money.

Stills

gallery is a substantial collection of photos taken largely by

Maureen Gosling covering a wide range of subjects and

divided into 12 categories. They are reproduced at close

to full screen.

Finally

there two non-DVD-based extras in the shape of an essay

on the film by author Paul Arthur entitled In Dreams Begins Responsibilities, and an accompanying book featuring Les Blank

and Maureen Gosling's on-location diaries.

These document both visits to the location and record

not only the events and the details of day-to-day life in

the location camp, but also the attitude of the pair to

this sometimes arduous adventure. There is an overlap

with information supplied in the commentary, but this

is still enthralling reading, in part for being a non-retrospective

(and thus sometimes very directly honest) view of the

shoot.

Burden

of Dreams remains one of the most compelling visual records of the

film-making process, in part because it is about more

than that, but mainly because the its subject and participants

are just so damned interesting. That it feels a few shades

short of complete is not really a problem, as what is

there makes for fascinating viewing, and the film is very

well supported here by supplements that allow some critical

feedback from the film's principle subject, a rarity in

itself. Criterion have once again come through here, delivering

a fine DVD of a film that should prove essential viewing

for all of those interested in just how hard it is to

pull realise a cinematic dream, and just how far someone

of vision and determination will go to do so.

|