|

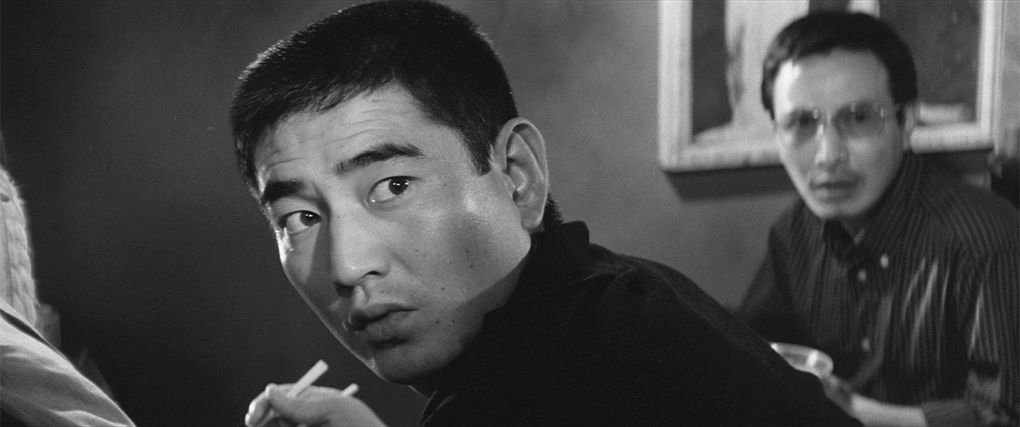

It begins like this. On the outer fringes of an unspecified city, brothers Kuroki (Mikuni Rentarō), Jirō (Takakura Ken) and Sabu (Kitaōji Kin'ya) all dream of escaping from the slum town into which they were born. One day the eldest brother Kuroki departs, and is followed five years later by middle child Jirō, leaving their mentally unstable and dementia-afflicted mother in the sole care of the furious Sabu. After trying to make his own way as a petty criminal and having his request for assistance angrily rebuffed by Kuroki, who has joined the Iwasaki yakuza, Jirō meets and teams up with amoral opportunist Mizuhara (Murota Hideo). Together they achieve degree of underworld success, but their increasing notoriety attracts the attention of the Iwasaki bosses, who dispatch foot soldiers to bust up their operation and set Jirō up to take the fall, which results in him being arrested and banged up in jail for several years. For many filmmakers this would be the basis for the first third of their film, but in the 1964 Wolves, Pigs and Men [Ōkami to buta to ningen], director Fukasaku Kinji is having none of it. Here that entire setup plays out under the main title credits as a dizzying montage of still images, short film clips, freeze-frames and superimposed shots set to Tomita Isao's free jazz soundtrack and Jirō's first-person narration. Total runtime: 2 minutes and 43 seconds.

The main story begins a few years later when the newly released Jirō returns to the slum in which, according to his own opening narration, "pigs pretending to be men live." He arrives just in time to block the progress of a lorry in which Sabu and his friends are riding, along with a home-made coffin containing the body of the brothers' recently deceased mother. Sabu clearly still has contempt for Jirō, and after terse a brief exchange, he and his friends resume their journey.

Later in his bay side apartment in town, Jirō shares his dream of fleeing the country and starting anew far away with his girlfriend Kyōko (Nakahara Sanae), and when she asks where they'll get the money to do so, he assures her that in two days he'll have 20 million yen. Elsewhere in the city, meanwhile, Kuroki has been newly promoted to the position of manager of a plush nightclub by his yakuza bosses, who have just arrived to inspect their latest investment. They appear to have confidence in Kuroki's abilities but are concerned that Jirō has been released from prison and suggest that Kuroki meet with him and find somewhere to put him where he can be kept in check. The meeting is then unexpectedly disrupted by the arrival of Sabu bearing a white cloth-wrapped box containing their late mother's bones, which comes as a jolt to Kuroki, who wasn't even aware that she had died. As the heated conversation between them risks putting Kuroki's trusted position with the Iwasaki bosses in jeopardy, Kuroki gives Sabu some money to find a good resting place for their mother's remains. Instead, Sabu and his friends head down to the waterfront and toss the container into the bay and watch on intently as it slowly sinks. As they do so, they break into a finger-clicking a cappella song whose lyrics capture their collective desire to leave this town and travel to some unspecified and presumably distant place, a dream they unknowingly share with Sabu's brother Jirō. It's an unexpected but oddly captivating sequence that has faint echoes of West Side Story and looks forward, in its way, to the musical pauses in Suzuki Seijun's 1966 hyper-stylised yakuza cult favourite, Tōkyō Drifter [Tōkyō nagaremono].

At this point, Fukasaku is still effectively setting up the story, a process that continues when Kuroki makes an unannounced visit to Jirō and hands him a tidy sum to leave town. It's money that Jirō happily accepts, but despite superficially accepting Kuroki's condition, he's not going anywhere, at least not yet. Unbeknown to Kuroki, Jirō and Mizuhara have discovered where and when a big drug deal is to be conducted and are finalising plans to steal both the money and the drugs, which they estimate will net them the millions that will allow Jirō to start a new life abroad. To assist them with the heist they elect to hire Sabu and his friends, offering to pay them well for their assistance but fully intending to rip them off and disappear with the spoils. The only thing is, the drugs that they are planning to steal belong to the Iwasaki yakuza group, the very organisation for which Jirō's brother Kuroki works.

Against all odds, the robbery itself proves to be a model of efficient planning, with the two targeted parties set to exchange bags in the theoretical anonymity of a crowded railway station concourse. Security will be light to avoid attracting police attention, and come on, who would be reckless or stupid enough to rob the yakuza? With Sabu and his friends staging a brawl as a distraction, Jirō and Mizuhara sneak up behind their victims and force them at gunpoint to don blacked-out sunglasses, blinding them long enough for Sabu and his gang's only female member Mako (Shina Hiroko) to grab both bags and flee, leaving Jirō and Mizuhara to follow suit and disappear into the crowd. It's a superbly staged set-piece whose energy, invention, economy and disarming realism (the sequence was shot in Tōkyō's busy Shibuya station with the public unaware that they were being filmed) matches the pitch-perfect execution of robbery itself. It's only after everyone safely makes their escape that this seemingly perfect plan starts to sour, and while the robbery is unquestionably the film's showpiece scene, it's what follows that provides its real dramatic meat.

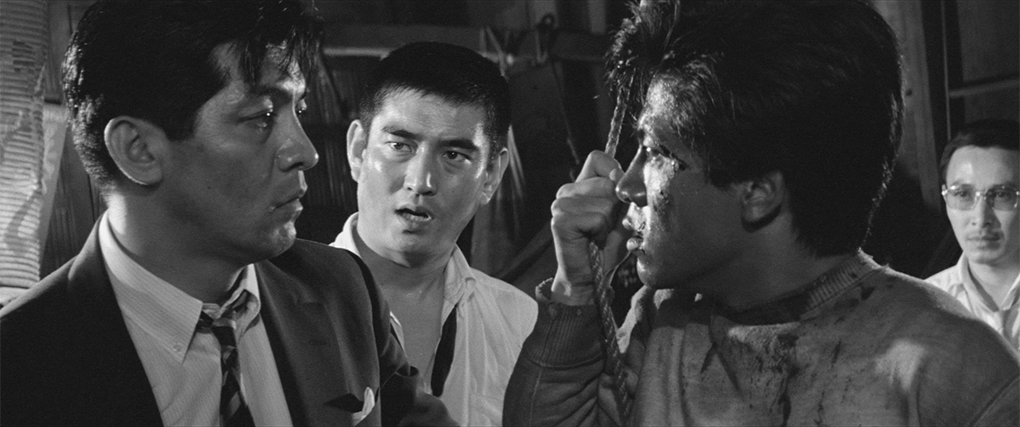

Given the setup, the characters, and the fractious relationship between the three brothers, it should come as no surprise that things quickly fall apart from here. In this world, there really is no honour amongst thieves, and trust and loyalty are in equally short supply. Despite their years apart, Sabu knows Jirō well enough to suspect he'll rip him and his friends off from the moment they agree to assist with the robbery, and he thus takes the precautionary measure of disappearing with the stolen money and hiding it somewhere before Jirō reaches the hideout. This puts a spanner in Jirō's intended betrayal and also scuppers Mizuhara's plan to stiff his partner and take the whole lot for himself. That said, it also ends up reuniting them in an effort to force Sabu to reveal where he has hidden the stolen money and drugs. To that end, they lock Sabu and his comrades in the hideout basement and try to force them to talk by individually torturing them in clear earshot of their friends. It's here that we first get to witness the uncompromisingly tough edge that Fukasaku would later bring to acclaimed yakuza films like Battles Without Honour and Humanity (Jingi Naki Tatakai, 1973), Graveyard of Honor (Jingi no Hakaba, 1975) and Yakuza Graveyard (Yakuza no Hakaba: Kuchinashi no Hana, 1976). Don't let the 1964 release date fool you, as even today these scenes are convincingly nasty enough to have you wincing and inspire the odd gasp of shocked surprise. And maybe it's just me, but the red blood that flows from wounds on colour film always looks grimmer when visually and tonally blackened by monochrome stock.

On his commentary track, Japanese cinema expert Jasper Sharp makes a persuasive case for the importance of Wolves, Pigs and Men in the development of Fukasaku's film career and Japanese crime cinema in general, and even if you put this aside (and you shouldn't), as a tough, nihilistic crime drama, it's an absolute belter. The screenplay, by Fukasaku and Satō Jun'ya, is superbly structured, being built around a story with three socially distinct but interconnected levels, each of which is defined by the clothing worn by the individual brothers. Kuroki now holds a managerial position in the yakuza and is kitted out in an expensive suit and bow tie, the baggy street clothes that Sabu wears are dirtied by the slum he has so far been unable to escape, and somewhere in the middle sits the cocksure Jirō, who dresses to project a false image of dangerous cool. Once members of the same family, the three are now separated by the criminal class structure. Hence, the wannabe middle-class Jirō is willing to coldly exploit and financially cheat the working-class Sabu, both of whom are regarded as little more than a nuisance by the ruling class into which Kuroki has wormed his way.

As a drama, the film grabs you from that opening prologue and never lets go, but really tightens its grip following the electrifyingly staged robbery, and particularly once Jirō and Mizuhara imprison Sabu and his friends in the basement of their slum hideout and start torturing them for information that they ultimately unite in the determination not to spill. Curiously, while the opening narration seems to set Jirō up as the central character, it becomes increasingly clear that this position really belongs to Sabu, who has more integrity and loyalty in his broken fingers than the duplicitous Jirō possesses in his whole body. And while Kuroki seeks power and privilege and Jirō thirsts for wealth, Sabu is the only one whose life is enriched solely by the friends he keeps. It's a positive trait that cheerfully explodes following his mother's watery funeral, when he and his companions take the money given to him by Kuroki and throw a party, at which they drink, dance and sing like they don't have a collective care in the world.

Although an ardent fan of Fukasaku's later yakuza films, I'd never previously seen this breakthrough crime drama and loved every energised, inventive, if ultimately downbeat bit of it. I've only hinted above at the satisfying density of the interlocking three-tiered narrative development and the nastiness of the torture of Sabu and his friends, which includes violent beatings, the crushing of fingers in a vice, and even what is clearly inferred to be a rape, still startling content for a film released back in the mid-1960s. Yet there's nothing gratuitous here, just an honesty about the lengths violent and amoral men will go to in a world in which that violence in not just physical but societal, as evidenced by the slum conditions that those at the bottom of the social strata are forced to endure. It's a heady and pessimistic, almost noirish tale of sibling rivalry, friendship and loyalty dressed in crime drama clothing, one that flies in the face of Japan's economic turnaround and new optimism of the day. Rivetingly directed and impeccably performed, it's a key work in the development of what would prove to be a renaissance for Japanese gangster cinema, and a career turning point for one of its most talented and influential practitioners.

A restoration of the original film elements supplied by Toei, the 1080p, 2.40:1 transfer on this Eureka Masters of Cinema Blu-ray is a robust one whose best material is in excellent shape. Some of the wider location shots are not as crisp as others, and the black levels soften a tad in some darker sequences, but elsewhere, particularly on studio filmed mid-shots and closeups, the image quality is close to excellent, with nicely graded contrast and sharply defined detail. The image sits robustly in frame throughout, and there is almost no trace of dust or damage – only on a few shots did I see minor traces of former wear.

The Japanese Linear PCM 2.0 mono soundtrack has the expected range restrictions, but is otherwise in good condition, with clear presentation of the dialogue and score, and no obvious signs of wear or damage.

Optional English subtitles kick on by default but can be removed if you so wish.

Audio Commentary by Jasper Sharp

Critic and author of several books on Japanese cinema, Jasper Sharp, delivers an information-crammed commentary on what he describes at one point as "an angry, pessimistic and cynical film." He explores the careers of Fukasaku Kinji, co-screenwriter Satō Jun'ya, score composer Tomita Isao, and several of the main actors, and details why he considers this such a crucial film for both Fukusaku and for Japanese cinema. He emphasises this point by noting that "with regards to the evolution of the crime film in Japan, its brand of pessimism, social commentary and violence was well ahead of its time." He outlines the positive changes that were occurring in Japanese society that the tone of this film kicked resolutely against, discusses how gangsters tended to be portrayed in the cinema of the day, and even recalls how a first viewing of this film at a Fukasaku retrospective in Rotterdam in 2000 was part of the spark that led to him and fellow Asian cinema guru Tom Mes creating the excellent Midnight Eye website. There's loads more here, all of it fascinating, and the sheer number of related titles cited by Sharp provided me with a lengthy list of films that I was previously unaware of that I am now keen to see.

Socially Aware Violence – Interview with screenwriter Satō Jun'ya (20:14)

The film's co-screenwriter Satō Jun'ya recalls how the script for Wolves, Pigs and Men came about, and reveals that while Fukusaku liked to drink, he was not allowed to do so when working (!) or writing scripts and believed that stories should not be told under the influence of alcohol. Tell that to Bruce Robinson. He answers captioned questions about Takakura Ken, the use of violence as a motif, and the film's social commentary subtext, and he claims that Fukasaku was not keen on making this film but was ultimately pressured to do so by Toei. When asked for his own view of the finished film, he is curiously evasive, rather damningly suggesting instead that in order to make a living, creators had to do what the studio demanded, which sometimes meant making things they were not proud of. For reasons that are not explained, the 16:9 image is heavily cropped at both sides, suggesting that the interview was shot in a vertical format (oh, surely not…?) or that the masked areas contained something we were not supposed to see.

Slums, Stars & Studios – Interview with producer Yoshida Toru (20:36)

Unlike the more hesitant Satō Jun'ya, producer Yoshida Toru is an enthusiastic and jovial talker (his interview also fills the 16:9 frame), with plenty to say about the production of Wolves, Pigs and Men. He recalls how frustration at his early career as a studio facilitator almost prompted him to quit, and how the appointment of 37-yea-old Shigeru Okada as Tōkyō branch manager quickly changed his mind, how his love of French literature indirectly led to him meeting Fukasaku, and sets the scene for the inception and production of this, the first of seven films that they made together. He recalls how smallpox-carrying mosquito-infested slum location shoot that was made even tougher by a conflict between Fukasaku and actor Mikuni Rentarō, and suggests that the film was not a financial success because the production company abandoned it. "I can't understand why this project was approved," he claims. "It's such a dark story. But it happened by chance." This is just a sampling from a hugely engaging interview.

Yamane Sadao on 'Wolves, Pigs & Men' – 2017 interview (12:28)

A 2017 interview with Fukasaku's biographer, Yamane Sadao, who links the bleakness of this film to the uncertainty about the future in post-WWII Japan, praises its documentary feel and confirms that the robbery sequence was filmed without informing the public what was happening, confirms the influence of Italian neorealism, and recalls first seeing the film as he was leaving college and thinking, "It was like, 'That's it!' for us." He reveals that during filming, actor Takakura Ken was dividing his time between this and the simultaneously filmed Brutal Tales of Chivalry (Shōwa zankyō-den, 1965), in which his character was the moral opposite of the one he plays in Fukusaku's film, and explains why in his opinion Wolves, Pigs and Men is "the number one masterpiece" of Fukasaku's early period. We are informed up front that the original footage of this interview has been lost, but a timestamped edit of the final cut was saved, from which this material has been taken. Just ignore the timecode in the top left-hand corner.

Original Theatrical Trailer (2:53)

A solidly assembled trailer that doesn't shy away from the second half violence and sexual assault, but impressively doesn't try to sell the film on these aspects alone.

The release disc also includes a Collector's Booklet featuring new writing by Japanese cinema expert Joe Hickinbottom, but this was not available for review.

A key film in the career of co-writer and director Fukasaku Kinji and also a cracking noir-inflicted, socially conscious crime drama in its own right, Wolves Pigs and Men is an absolute must-see for fans of gangland crime movies and especially those with a penchant for the tough Japanese yakuza tales that followed in its wake. It's another top-notch release for Eureka's Masters of Cinema label, with a quality transfer and some very fine special features making this an easy one to highly recommend.

The Japanese convention of family name first has been used for all Japanese names in this review.

|