|

Do you like Star Wars? I mean the original Star Wars when it was still called Star Wars and hadn’t been rejigged and rebranded by George Lucas when he realised there were billions to be made from turning it into a seemingly endless franchise. And are you not so precious about it that you rather enjoyed the stream of often cheapjack space adventure rip-offs that followed in its wake? What about optical effects? Are you wedded to modern-day CGI, or do you still have a warm pace in your heart for low-budget, hand-drawn laser beams and electrocution flashes? Were you a fan of cheesy sf TV series like Buck Rogers in the 25th Century? What about visions of the future where young people dance to disco music that was already out of date when the film was released? And are you tickled by the idea of a Japanese live action science fiction anime whose sometimes manic handling and complete disregard for scientific logic makes you wonder if the director was popping amphetamines throughout the production? If all of these appeal, then boy do I have a treat for you, but if you involuntarily winced at any of the above, you’re going to have a few serious problems with the 1978 Message from Space [Uchu kara no messeji].

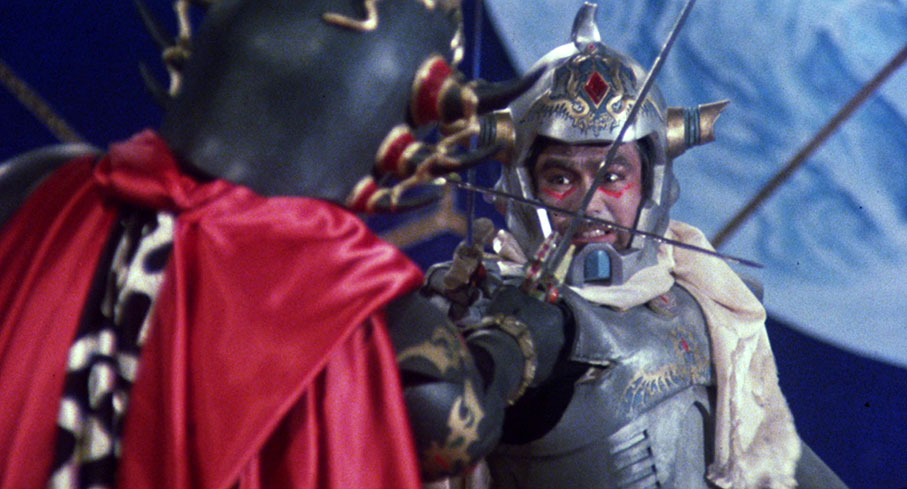

It kicks off on the distant planet of Jillucia, whose population has been reduced to a small pocket of people whose threadbare attire visually aligns them with the mud-hunting peasants in Monty Python and the Holy Grail. These desperate individuals are the last survivors of a planetary invasion by the Gavanas, a cruel and technologically superior race who are led by Emperor Rockseia XII (Narita Mikio) and whose alien status is indicated by their silver faces and plastic ceremonial armour. With their situation now desperate, Jillucian leader Kido (Junkichi Orimoto) stands before his people holding eight Liabe seeds (which look suspiciously like walnuts) and calls on the Holy Spirits of the Universe to propel them into the far reaches of space to find eight brave warriors to come to the aid of the Jillucian people. He then instructs his granddaughter Emeralida (Shihomi Etsuko) – who clearly has access to a far better tailor than her subjects – to follow the seeds and bring the selected warriors back to Jillucia. A subject named Urocco (Satō Makoto) then steps forward and insists that he join Emeralida as her protector. “Yes,” Kido replies, “if a strong man like you accompanied her, she will surely succeed.” The idea of a bodyguard for his young granddaughter had clearly not occurred to Kido before Urocco volunteered himself for the task. My faith in this supposedly wise old leader quickly began to wane.

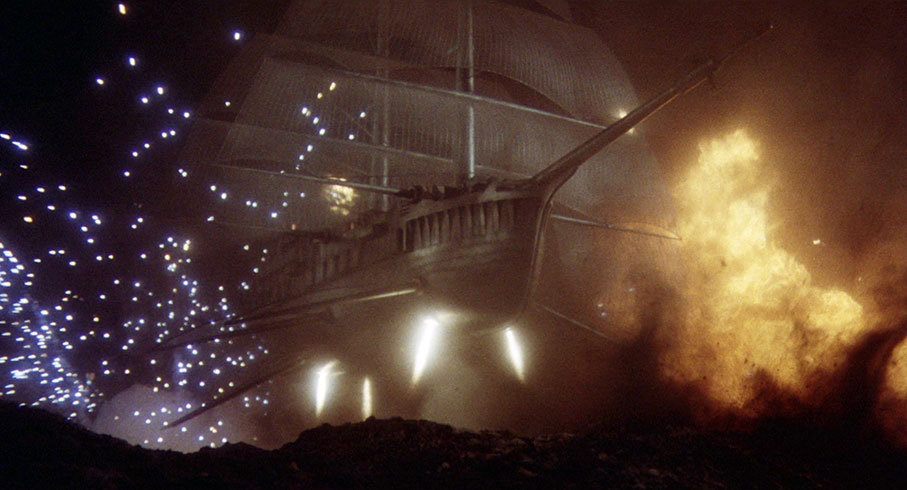

What I wondered next was how the seemingly primitive Jillucians could hope to send two of their people into space. Well, it turns out that despite having no homes, no transport and no weapons, they do have an exquisitely crafted spaceship safety tucked away from prying Gavanas eyes. And when I say spaceship, I actually mean ‘space ship’, an old school galleon of the sort that Earth-bound explorers once sailed across oceans to discover and plunder countries and fight naval battles, but one that defies gravity and uses rocket boosters to push it towards the heavens. Not quickly, mind you, but then, what’s the hurry? The Gavanas detect the ship’s departure, but it’s moving too slowly for their laser cannons to destroy it, I guess, and Emeralida and Urocco thus make their escape relatively unscathed. Just how this craft can cover a two million light year journey in a few days will forever lay beyond my comprehension.

So in the course of searching the entire universe for heroes, who do you think the Liabe seeds will find? Fearless and morally upright heroes in the Japanese samurai tradition? Of course not. If you thought daydreaming farm boy Luke Skywalker was ill-prepared to take on the Empire and save a captured princess, just wait until to see who’s tasked with the job here. First up we have Meia (Peggy Lee Brennan), the pampered daughter of a wealthy but narratively insignificant somebody-or-other, who is first shown sipping a cocktail in a small but luxurious star cruiser on which she appears to be the only passenger. When she asks the Captain (William Ross) about the twinkling lights she can see through the window, he tells her that they are radioactive particles known as space fireflies, a romantic notion that Meia is enchanted by. The ship is then violently rocked when the pilot has to swerve sharply to avoid a couple of interstellar hotrodders who fly suddenly into its path. The space jocks in question are close friends Shiro (Sanada Hiroyuki) and Aaron (Philip Casnoff), and while their antics infuriate the star cruiser crew, they delight the increasingly excitable Meia. She insists that they follow them and tries so aggressively to grab the controls that the Captain comes close to having to wrestle her forcibly to the floor. Seconds later, Shiro and Aaron’s antics attract the attention of a police patrolman, and a high speed pursuit ensues that the boys escape by executing what Shiro dubs “the chicken run.” This involves flying at high speed towards the surface of a nearby planet and pulling up just before they hit the ground, a manoeuvre that the two boys pull off with confident aplomb. The panicking police patrolman somehow follows suit, only to then clip a couple of tall rock formations and come crashing to the ground, while Shiro and Aaron continue to show off their piloting skills by hurtling their craft through a narrow rock tunnel. There’s a little bit of foreshadowing there for those paying attention. Just seconds after triumphantly emerging from the tunnel, both ships blow the space equivalent of a gasket (and I don’t even know what that is) and end up skidding to a halt on the planet’s surface. In a moment that made me giggle, and for all the right reasons, Shiro immediately hops out of his craft and starts blasting the smoking vessel with a cosmetically redressed modern-day fire extinguisher. When he and Aaron examine their respective engines they discover that both malfunctions were caused by large and mysterious, walnut-shaped seeds. Aha…

Next we meet military officer General Gulda (Vic Morrow – yes, that Vic Morrow), who has organised an official parade – one that his reluctantly obedient soldiers take as a sign that he’s losing his marbles – to launch the body of his recently deceased close friend Beba into space. Only when his outraged superior officer calls him up demanding to know what the hell he thinks he’s up to do we discover that Beba was not a human but a robot. And Gulda is so upset by the loss of his mechanical friend that he’s already replaced him with a presumably identical model that he’s given the inventive name of Beba-2. And boy, did I find this robot annoying. It’s not that it’s a kid or a small person in a plastic robot suit, as the suit itself is pretty good as these things go. It’s when the bugger speaks that I started twitching in my seat. Voiced by doubtless talented actress Soga Machiko, Beba’s every line is delivered as an eardrum-piercing, child-like screech that’s been processed through a stadium Tannoy system. Late in the film, when Beba is on lookout patrol armed with a musket that its fingerless clamp hands could not possibly fire, it makes a discovery that gets it so excited that I was convinced its shrill wittering would shatter all of the windows in my house. Averse to English dubs of foreign language films though I am, this is one area in which the redub definitely trumps the original. Beba may still be irritating there, but it’s far less abrasively voiced.

Depending on whether you watch the film with the Japanese or English track enabled, Gulda is either fired for his actions or has already submitted his resignation by the time the angry call from Central Command comes in, and it’s when he hits a bar to sink a few in memory of his departed robot friend that all the plot strands start to interconnect. Just as Gulda finds his Liabe seed in a glass of Space Scotch, sitting at a nearby table playing cards is the film’s human litmus test for audience tolerance in the shape of a Japanese man with the very English name of Jack. Oh, what to say about Jack? For a start, he dresses like a holiday camp entertainer in a jacket so colourfully garish that it would make even Liberace wince, and if that’s not enough, the design is repeated on the hat band of his boater. He reacts with exaggerated excitement to just about everything, and I’m still not sure if his front teeth are an intended comical addition or the set that actor Okabe Masazumi was blessed with from birth (my sincere apologies to Masazumi if it’s the latter). Some will find his antics amusing, but I found myself all-too-frequently wanting to slap him. Anyway, Jack’s game is interrupted when a rotund and almost as flamboyantly dressed gangster demands the immediate return of some money that he foolishly asked Jack to secure away. Trouble is, it turns out Jack’s loaned it out instead to none other than Shiro and Aaron, who’ve already spent it on spare parts for their ships. In a surprise reveal, they’re not the rogue space cadets I assumed that they were, but washer-uppers in the kitchen of this very establishment. The gangster furiously gives them just 30 minutes to return his money (not going to happen) and throws Jack violently across the kitchen to hammer home his words. After losing his rag in a screaming fit at Aaron and Shiro, Jack bites into a tomato and nearly breaks one of those splendid teeth on – you’ve guessed it – the hard outer shell of a Liabe seed. Just as the three men are comparing their identical discoveries, who should waltz into the kitchen but Meia, who is somehow friends with the penniless Aaron and Shiro and who cheerfully tells them that she’s stuck here after causing the pilot of the star cruiser to panic and crash. Ah, what a joker. Being from a rich family, she agrees to give the boys the money they need to pay off the gangster, but on the condition that they assist her in her quest to catch some of the space fireflies she found so enchanting. Erm, will you tell her or shall I? This means breaking galactic law again, but the boys are desperate and thus agree to her terms.

The above might seem like a shedload of setup plot, but by this point we’re a mere 20 minutes into a 105 minute film and I’m only covering the basics here. The individual members of the team are still some way from assembling into a united group, and despite the fact that they’re in the same bar, Gulda does not cross paths with the other Liabe seed recipients until later. They’ve also all yet to meet up with Emeralida and Urocco, and given the infinite vastness of space, the chances of them encountering each other are surely next to impossible. Oh, wait, I forgot about the narrative usefulness of fate and the magical power of the Liabe seeds. Those with impeccable mathematics skills will also have realised that only five of the seeds have so far found their targets. Who else might they seek out? That’s not for me to say, though one did make me groan, while another, played by the always splendid Sonny Chiba, proves to be the most obviously deserving of selection. The journey to the inevitable climactic battle is also peppered with hiccups and narrative diversions. One of the group is revealed to be a duplicitous bastard, which has unexpectedly dire consequences for one of his companions, which in turn eventually prompts a guilt-driven moral about-face. Commitment to the cause also wavers more than once, with Shiro, Aaron and Jak at one point throwing their seeds away, which stokes division in the group when they rethink their position but only two of the seeds return to their original owners.

Although technically qualifying as science fiction, a better fit for Message from Space would be science fantasy, or perhaps even fantasy science, with the plausible physics of spaceships and weaponry doing battle with a complete disregard for scientific logic elsewhere. Thus, while I saluted the forward-looking notion that the wireframe sails on Emeralida’s galleon starship were drawing solar energy from the stars to provide it with power, I sat open-mouthed as Meia, Aaron and Shiro exited their ships and cheerily swam around in space with only small oxygen masks for protection. Later, these three decide to combine their individual ships into a single vessel that can unfold in flight in order to allow Aaron and Shiro to mount separate attacks. It’s a great idea, and the resulting ship is really impressive, but it would take NASA’s top engineering team working around the clock for at least a couple years to construct. Here it’s knocked together in an afternoon by these three with a blowtorch, an adjustable spanner and a drill.

It's hard to be sure how much of the film you’ll need to see before it clicks that it’s seriously riffing on Star Wars, particularly given that the promotional material for this Blu-ray release makes a play of this fact. Even without this foreknowledge it shouldn’t take you long. Ingeniously, while Message from Space was hurriedly set in motion in response to the blockbuster success of George Lucas’s film, it was completed and released several months before Star Wars hit Japanese cinemas. As it happens, the core plot is actually very Japanese in origin, dating back two centuries to an epic novel titled Nansō satomi hakenden (which apparently translates as Eight Dog Warriors), a tale that appears to have also inspired the plot of Kurosawa Akira’s Seven Samurai (Shichinin no Samurai, 1954), which is sometimes (incorrectly) cited as a key influence on this film. But Star Wars casts an even bigger shadow here. You have a princess whose home planet is threatened by a race of evil uniformed oppressors, a duo of Luke Skywalker stand-ins and a female Han Solo, and instead of a Death Star, the Gavanas have fitted gigantic boosters to the surface of Jillucia to enable them to fly the whole planet across space. When they reach Earth, they demonstrate their destructive capabilities to Chairman of Earth Council, Earnest Noguchi (Tamba Tetsuro, another serious coup) by blowing up the moon. Wait until they see what this dramatic shift in gravitational pulls does to the seas and weather on the planet Emperor Rockseia has set his heart on conquering. A couple of attempts are made to emulate that extraordinary opening shot of Lucas’s film on a smaller scale, a climactic high speed dash through tunnels to blow up a reactor is an unashamed reworking of Luke Skywalker’s flight down the Death Star trench, and the sequence in which Luke jumps into a gunnery pod of the Millenium Falcon to fight off TIE Fighters is recreated almost verbatim here.

Yet despite the scientific silliness, the anime-inspired costume designs, the larger-than-life performances, and characters that that are not exactly easy to warm to, director Fukasaku Kinji – yes, he of Battle Royale (2000), Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970) and Battles Without Honour and Humanity (1973) – and his team clearly wanted to get one up on Lucas in advance of his film’s release through the sheer intensity and pace of the spaceship effects and model work. They may not have the sense of real world scale of the Star Wars vessels (unlike those ships, the ones here do tend to look like the models they are) and owe as much to Thunderbirds era Gerry Anderson as they do to Industrial Light and Magic, but compensate somewhat through their speed and manoeuvrability, swooping around the sky and through tunnels like hyperactive swallows as the camera whips and chases in an attempt to keep pace. Indeed, so frantically shot and edited is one battle that I genuinely lost track who was shooting at whom and at one point who anybody was. And while some of the optical effects have dated, the ships are for the most part cleanly composited and interact with their surroundings in a largely convincing manner. There are some particularly impressive shots of ships slowly rising from or landing on planets that look almost almost like test runs for the Nostromo model effects in the following year’s big science fiction hit Alien, and when the vessel is later reduced to a burning wreck and begins to dive there’s a sense of scale – just look at the flames pouring out of every window – that is genuinely awe-inspiring. And by adapting elements from Nansō satomi hakenden, the film has a two-year jump on the enjoyable 1980 Roger Corman production, Battle Beyond the Stars (1980), which was effectively Seven Samurai in space.

If you buy into the promoted notion that Message from Space is a Japanese Star Wars and go in expecting a film as technically striking, wittily scripted, solidly acted and polished as that, then you may well wonder what the hell it is that you’ve been served up. But if you approach it prepared for its sometimes wobbly narrative, its hyperactive performances, its budgetary concessions, its more annoying characters and its complete disregard for scientific logic, you could have an absolute ball. Fukasaku’s sheer drive, coupled with the energised camerawork of his regular cinematographer regular Nakajima Tōru and the charged editing of Ichida Isamu (who also worked with Fukasaku and Nakajima on the 1976 Yakuza Graveyard), propel the whole venture forward at such a stonking pace that it’s hard not to be swept along in its slipstream. Yes, there are some daft moments, the stabs at humour don’t always translate, and despite the robustness and volume of model effects, there are a couple of gaping concessions to what I presume was the perceived need for haste elsewhere in the production. My favourite comes when the Gavanas use a probe to read the mind of a dying Earthling in order to gain a clear picture of the planet from which this unfortunate individual hails. What we get a short slide show consisting of a couple of images of mammals against a landscape, the face of a child, a few birds in flight, and the Earth viewed from space (and four of these pictures are shown twice), which prompts Emperor Rockseia to claim in awe that he’s never seen such a beautiful planet. Man, he really does need to get out (in space) more. Sure, Message from Space may borrow from a range of movies and genres, but it does so inventively and puts its own spin on every one of them – swap their spaceships for souped-up cars and the space lanes for highways and we’ve seen the likes of Shiro and Aaron in many teen-targeted movie before (the cop chasing them even wears an American Highway Patrol style crash helmet). And when the film is this good natured, this wildly energetic, this don’t-give-a-crap imaginative and this much fun, it gets a free pass from me on just about anything that might otherwise blot its grand galactic copybook.

Restored in HD from the original film elements supplied by Toei, the 1080p transfer here has to be easily the best the film has looked since it first hit cinemas. Framed in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1, this is not, perhaps surprisingly, a film whose visuals really pop from the screen, and the colour is never vividly bright and is even downright earthy at times, but the image is still crisp and detail well defined – just check out Garuda’s dress uniform when he meets with Emperor Rockseia if you’re looking for evidence. Occasionally, the picture softens a tad during process shots (the oxygen mask-assisted spacewalk is a prime example, which also has some of the brightest colour), but the transfer as a whole is clean and free of damage, and a very fine film grain is visible. A couple of shots as Meia, Jack, Shiro and Aaron find an unconscious Emeralida aboard her ship have some noticeable horizontal jitter. At first I thought this was a fault, but rewatching the film I have a suspicion that this was an optical effect added to simulate a tremor caused by the rumbling engines of the huge Gavanas ship that is approaching.

There are two soundtrack options, both of them Linear PCM 2.0 dual mono and both with their specific positives and negatives. The Japanese original is noticeably louder and clearer than the quieter and more sonically subdued English language dub, but also has a stronger treble bias, resulting in the letter S sounding as a short abrasive hiss almost every time it is spoken. This also contributes to the shrillness of the voice given to Beba-2, which switches gender on the English track and is less of an assault on the eardrums. Morioka Ken'ichirō’s score, however, has a richer feel on the Japanese track, and does not seem to suffer the same treble clipping as the dialogue. There is a faint hum on the Japanese track, but it’s hardly noticeable at normal viewing volume and all other traces of wear have been largely banished. A very small number of dust spots and the whiff of the odd scratch remain, but blink and you'll miss them.

Although no subtitle options are offered on the main menu, English subtitles are automatically activated if you select to watch the film with the original Japanese track, while if you choose the English language dub, they only appear to translate the Japanese credits. Both subtitle options can be switched off using the remote if you prefer.

Audio Commentary by Tom Mes

Anyone with an interest in Japanese film should know the name of Tom Mes, who co-founded and regularly reviewed for the website Midnight Eye and has continued to work as a writer and film historian, and Mes really knows his Japanese movies. He pegs Message from Space as “delightful” from the start, but also notes that it was one of many space-set science fiction films that followed in the wake of the success of Star Wars, “to the delight of children everywhere for years, even as they grew up and learned to appreciate the films for their campiness and their ‘so bad it’s good’ quality.” He looks at how changing trends in Japanese cinema and evolving audiences drew director Fukasaku Kenji to what on the surface might seem an unusual project for him, and makes a solid case for why his directorial stamp is all over the film. He discusses the origins of the story, notes the influence of post-WWII social attitudes on specific scenes, and cannily points out that the borrowings from Star Wars are part of a long-standing two-way process, as elements of Star Wars were lifted from Kurosawa Akira’s The Hidden Fortress (1958). There’s detail on the making of the film, its success and influence, and a fascinating discourse on the influence on productions in Japan and the US of related toy and model sales. There’s lots more here. I really enjoyed this.

Ah! Message From Space (14:26)

The author of Tokyoscope: The Japanese Cult Film Companion Patrick Macias puts his cards on the table at the very start with a brief self-directed Q&A that asks, “Is Message from Space the greatest Japanese movie ever made? Probably not. Is Message from Space my favourite Japanese film of all time? Yes indeed!” For all its many pleasures, it’s definitely not mine, but I loved Macias’s unbridled enthusiasm and passion for the film, and considering some of the suspect titles I’ve championed over the years, I’m with him all the way, in spirit at least. Being the personal favourite of a man who has authored a book on cult Japanese cinema, Macias appears to know even more about the film and its production than the learned Tom Mes, and thus expands on some aspects of the commentary, as well as providing details unique to this presentation. He is also able to draw on interviews he conducted with actor Tamba Tetsuro and director Fukasaku Kinji, who reveals that Vic Morrow was constantly drunk when filming, which casts and interesting light on the fact that his character is rarely seen without a drink in his hand. My favourite comment comes when Macias notes that the film has a kitchen sink quality to it, “as if everyone was shot out of a cannon through the props and costumes department of Toei Studios.” Once again, superb.

Message from Earth (30:15)

A 2011 German featurette on the making of Message from Space built around interviews with Fukasaku Kinji’s son Kenta (also a director), actor Sonny Chiba, special effects director Yajima Nobuo, and head of miniatures Hiruma Shinji, who outline the making and release of Message from Space from their individual perspectives. Fukasaku leads the way here, setting the scene in terms of the films with which his father had previously made his name, and recalling visiting the set at the age of five and deciding there and then that he wanted to be a director because he was having so much fun. An amused Chiba praises his director and recalls wanting to do whatever it took to make him happy, not always easy when he kept him up all night drinking sake. He confirms that the actors all delivered their lines in their native tongue, which caused problems when the non-English speaking Japanese performers were unsure when the American actors had finished their lines. He also provides a personal perspective on the on-set accident that resulted in him breaking his leg, noting that “an actor’s body is his language.” Yajima confirms that they wanted to complete the film and release it before Star Wars came out in Japan, and that he had the climactic battle planned out completely in his head and worked backwards from that. Hiruma is less complimentary, claiming that Yajima wanted him to start work on the spaceship models before there were any designs, then repeatedly pestered him to see if he had finished, resulting in sometimes heated arguments between the two. There’s loads more of interest, but I’ll sign off with Fukasaku’s sweet claim that when a lack of funding and access to technology really gets him down, watching Message from Space always cheers him up.

Stills Gallery #1: Promotional Materials

26 manually advanced screens featuring sharply detailed scans of international posters, concept art and technical drawings, including a breakdown of what the internal workings of Beba-2 would be if it was an actual robot.

Stills Gallery #2

A whopping 76 screens featuring photos taken on set during the film’s making, including several of the model work, plus a generous selection of promotional stills.

Trailer #1: Filming Begins (2:00)

“Something is happening in space!” Now this is interesting, a pre-release trailer with a few clips from the film and some cheerleading captions, but also footage of the American actors arriving in Japan and attending a press conference, though the whole thing is set to music lacking any live sound. There’s also a brief shot of Fukasaku directing, and a few model shots that have yet to be properly graded to make space look a little less like a bluescreen. Hardcore fans of the film should cherish this. This and the following two trailers are all Japanese in origin with burned-in and capitalised English subtitles.

Trailer #2: News Flash (2:07)

Similar to the above, but comprised entirely of clips from the film. The principle actors are introduced, the backgrounds on a few of space flight effects shots are still a little bright, and the emphasis is very much on the characters and action. There’s even a brief audible dialogue exchange between Gulda and Beba that suggests a third version of the film in which the actors all speak in their native tongue. Frankly, that’s the one that I’d most like to see, but it probably only exists in the extracts in these trailers.

Trailer #3: Wide Release (4:08)

An extended version of Trailer #2, with lots of effects shots, longer cast introductions, and a decent selection of dialogue and sound effects accompanying the music. Once again, while Japanese is spoken by the Japanese actors, the Americans deliver their lines in English. Was delighted to learn that the film was presented in “realistic sound system Space Sound 4.” Anyone know what happened to the first three?

US Release Trailer (2:50)

“A fantasmagoria of sights, sounds, and space-age technical achievements that must be seen to be believed.” Now it’s the American distributor’s turn to throw some verbal superlatives over a blend of action footage and character moments in which only the American actors get to speak, presumably in the hope that you won’t realise that the rest of the cast have been dubbed. To be honest this would probably have worked on me in my teenage years.

Also included with the release disc is a Collector’s Booklet featuring new writing on the film by Christopher Stewardson, but I don’t seem to have a copy of this so can’t comment further, but I’ve no doubt it’s worth reading.

It would seem that Message from Space has developed something of a cult following over the years, particularly amongst those who first caught it when it hit US cinemas on a double-bill with Luigi Cozzi’s Italian Star Wars rip-off, Star Crash. It’s not hard to see why. It’s as daft as an octet of glowing walnuts, treats scientific fact as a pesky inconvenience to be soundly ignored, and there are times when I struggled to believe what I was watching. But cut it the slack it deserves and it’s a whole barrel of innocent and inventive fun, one where the spaceships may still look like models, the actors sometimes play to the rear of the gallery, and director Fukasaku Kinji throws everything at the screen with the force and speed of a photon torpedo. How could I not love this, just a bit? Eureka clearly does, as it’s been released as part of the Masters of Cinema series, which I’m sure will raise the odd sniffy eyebrow. It gets my vote and then some, for the solid restoration and transfer, for the hugely informative Tom Mes commentary, for the making-of featurette, for the knowledge and enthusiasm of the immensely likable Patrick Macias, and even for the trailers, goddammit. If you think this might be your bag, you absolutely cannot go wrong with this Blu-ray.

As tends to be the way on Cine Outsider, all of the Japanese names here (with the exception of Chiba Shin'ichi, who is widely known now by his Anglicised stage name Sonny Chiba) follow the Japanese convention of family name first.

|