|

Down to the horrific torture devices Otakar Vávra's film vicariously punishes the viewer with, Witchhammer [Kladivo na čarodějnice] is a brutal yet fascinating picture to endure. The 1969 Czechoslovakian feature begins with a pounding musical score, moves into a bathhouse full of elegantly-shot (in black and white Scope) nude women and then quickly strips away any artifice of beauty amid a horrible, deeply wrong series of events based on court documents from the late 17th century. The topic, ostensibly, is a disturbing inquiry into witchcraft in a small Czech village. Audiences of the time might have detected a more allegorical slant – common in Czechoslovakian cinema of this time – aimed at the communist government.

Images of fingers and legs being forcibly crushed as (inky black) blood spills are tough to shake. While Witchhammer is hardly exploitative in its depiction of violence or female nudity the lasting impressions stick. On its surface, the film is decidedly less challenging than the typical release from its distributor Second Run, but the visual mementos are as undeniable as anything in the label's catalog. There's also a horror element and reputation which can feel somewhat misplaced upon viewing a film that, more often than not, features men in wigs sitting around a table talking. The terrifying aspect of the movie actually lies within the ideas passing through rather than the jumpy particulars of the mise-en-scène.

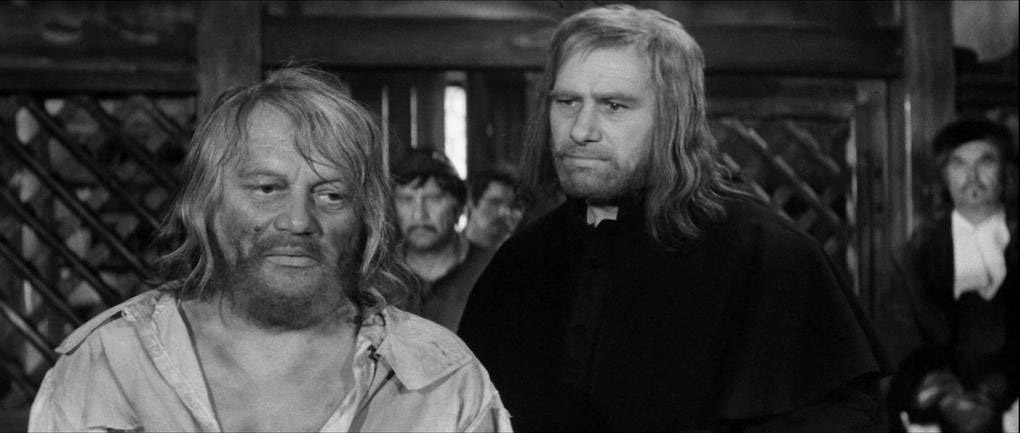

Whether the film is pro-religion, anti-religion or neutral is a debatable point, but the fact that the entire clusterfuck of misogynistic rat-traps kicks off with the theft of a Communion wafer shouldn't go unnoticed. The narrative segues from an elderly townsperson taking the cracker in hopes of healing a cow unable to produce milk into the terrible series of grotesqueries masquerading as criminal trials to determine who is and is not guilty of witchcraft. Leading the charge is Boblig (Vladimir Šmeral), a retired inquisitor now slithering out of his torpor and ready to do fresh damage to mankind. Over and over again we see women brought before a panel lead by Boblig, accused of cavorting with the devil in the woods and lasciviously succumbing to hedonistic desires. But the only truly diabolical figure is Boblig himself, a composite of history's hypocritical men in power who've made careers out of destroying others.

The initial group of declared witches are burned at the stake, in an incredibly vivid scene of pessimistic destruction. Present for the execution is the town's deacon, Lautner (Elo Romančik), who looks into the women's' faces and sees that, despite initial, torture-induced confessions, these are innocents being murdered. He brings his obvious reservations to the council. The backlash is then quick and unforgiving. Lautner is targeted, as are his friends and cook/love interest Zuzana (Sona Valentová). The film makes clear that anyone who runs afoul of the status quo will not only suffer but also have those close by fall prey to the beast. Lautner's downfall comes swiftly. All are subjected to horrendous torture techniques.

The justification for all of this comes from a text already three centuries' old during the events of the film. The Hammer of Witches, or Witchhammer, was a book declaring not only the existence of witches but the need to rid communities of them and even the means for doing just that via inquisitors. At the time of Vávra's film, the topic was a hot one recently explored by the Vincent Price-starrer Witchfinder General and soon on display in Mark of the Devil. While Witchhammer is clearly of a different strata, it embraces that element of outrage accompanying the systematic eradication of perfectly innocent citizens. The extra layer of having those accused being generally female further tarnishes the initial premise.

Surely the focus on attacking one gender over the other in an unfair power play would resonate at any time in history but now, at this very moment when abusive men are facing unprecedented consequences for their behavior, the message is transformed even further along the spectrum. If you happen to watch Witchhammer now it's likely to resonate differently than at perhaps any time in its existence. The clear takeaway is targeted oppression of women without any sort of justification. It's upsetting. That initial sequence of the nude women at the bathhouse seems to contrast the potential purity against the nasty, horrid treatment many will later face. It's a sharp line being drawn, and it's maybe not for us to fully comprehend the repercussions.

None of this is to denigrate the film in its existent form. The overall mood and tone of the piece is one echoing the seething anger inherent to what was occurring, but there's real dramatic value here, particularly in the second half once Lautner finds himself on the wrong side of the inquisitors. Prior to that Witchhammer can seem, narratively at least, familiar and beholden to the expected. Once the general idea of what's going on is relayed then the pieces fall predictably into place leading up to Lautner's ordeal. It makes for a rousing finish, depressing and sad but affecting overall. Czech films of this time tend to share similar lasting impressions of making sure to relay a sense of hopelessness against the glimmer of defiance and acknowledgement of what's occurring. One gets the sense, repeatedly, that despite recognizing the wrongdoing there's also a commitment to making sure everyone knows how widely their eyes are open to the circumstances.

Second Run has become increasingly bold in its Blu-ray choices. For a boutique label reluctant to expand into high definition for several years the decision to use a solid yet imperfect print to give this particular film its world premiere Blu-ray release seems like a calculated risk. The region-free aspect and the newfound commitment to including nifty extra features gives potential purchasers a bit more incentive to take the plunge.

The film is listed as originating from a new HD re-master and transfer from original materials via the Czech National Film Archive. It's presented in the 2.35:1 aspect ratio, making for often striking black and white Scope compositions. There are several instances of dirt, speckles, and reel markers still present in the print. Sharpness remains impressive, however, and contrast also looks quite good. Around the 79th minute there's a quirk with something that seems to be a missing frame. Overall, though, the image quality is very good, just not without blemishes here and there.

Audio is a Czech 2.0 Dual Mono LPCM track. Most everything here is clean and clear. Eight minutes or so into the picture a noticeable drop-out occurs but there were no nagging issues that I noticed. Dialogue and the score by Jiří Srnka sound consistently strong. English subtitles are optional, white in color.

The Womb of Woman is the Gateway to Hell (22:21)

A nice video appreciation on the disc, written and narrated by Kat Ellinger, takes its name from a phrase in the film. It's nicely put together, produced by Michael Brooke, and informative. References to other works abound, notably with Dreyer's Ordet, and then to other Second Run releases like Vlacil's Marketa Lazarova and The Valley of the Bees, and Dragon's Return. Those looking for some apt comparisons might appreciate the connections, though anyone with the disc should probably wait until after viewing the film to watch Ellinger's contribution.

The Light Penetrates the Dark (Svetlo proniká tmou) (4:46)

A short film Witchhammer director Otakar Vávra made in 1931 has also been included on the disc. Set to a frenetic piano score, the short begins with an unsubtitled screen of text and then moves on to black and white images of unspooling thread, spinning globes and various shots of lights. Very atmospheric, with hints of the avant-garde.

Booklet (16 pages)

Featuring a new essay on the film by Samm Deighan, this insert is of the usual Second Run standard and format. Deighan's piece tackles everything from the origin of the Witchhammer text to comparisons like Haxan and Ordet, as well as Nazi-era depictions of the devil in film. The booklet also has a most welcome single-page excerpt from an interview Vávra gave for a 2009 television show. Here the director links his movie to the 1952 Rudolf Slánský show trials (with some context provided in a footnote). There's also a paragraph where he talks about co-screenwriter Ester Krumbachová, a significant figure in the Czech New Wave who co-wrote Valerie and Her Week of Wonders, The Party and the Guests, and Daisies, among others.

Remarkably relevant and as upsetting as ever, the 1969 Czech drama Witchhammer is horror of a philosophical and political sort. Sometimes allegories age poorly but this one most certainly has not. Second Run's release is filled with strikingly unsettling black and white images - with the dark mood enhanced by close-ups of a disgusting, cloaked figure spouting hateful justifications - and does full justice to Otakar Vávra's film.

|