|

If, for whatever reason, you've landed on this review on this site by choice, then I'm guessing that you've probably heard of acclaimed German filmmaker Georg Wilhelm Pabst. There's also a good chance you've seen at least one of his two most internationally famous films, both of which starred American icon Louise Brooks. His 1929 Pandora's Box [Die Büchse der Pandora] is still regarded as one of the greatest works of silent cinema and was the first ‘serious' silent feature that I remember seeing. He followed this the same year with Diary of a Lost Girl [Das Tagebuch einer Verlorenen], a gorgeously made, compellingly acted and emotionally devastating drama of a young and innocent girl's tragic fall from grace. By the time he came to direct these seminal works, Pabst had already built himself a reputation as one of Germany's finest filmmakers, though as far as I'm aware the titles with which he first made his name have yet to find their way onto UK Blu-ray or DVD (if you're willing to dig deep, you can still find a couple on American DVD). But it was with the coming of sound that Pabst's left-wing humanism and pacifist convictions really found their voice, first in the 1930 WW1 anti-war film, Westfront 1918, then in the 1931, true story-inspired plea for international solidarity, Kameradschaft. Both have been restored and most appropriately paired on this new dual format release from Eureka's Masters of Cinema label, and both are genuine masterpieces of type, technically brilliant and emotionally affecting films that feel years ahead of their time, works whose passionate pacifist message so angered the fast-emerging Nazi party that they banned both titles when they rose to power.

I've seen a solid case made for the claim that all great war movies should by default be anti-war movies. Certainly, when I began listing the genre titles that I hold in the highest esteem, they either fall squarely into this category or contain elements that lean heavily in that direction (think the nightmarish Do Lung bridge sequence from Apocalypse Now). It's been convincingly argued that even seemingly justifiable wars are often the result of questionable or even criminal political dealings at an earlier date, and that armed conflict should always be a last, desperate resort in the complex world of fractious international relations. It's no coincidence that in every vision of a future utopia I can readily recall, war has been eliminated and the very concept of it is regarded as barbaric and the result of primitive thinking and behaviour.

Few of us in the west have any concept of what it is like to fight in or even live through a war, particularly one that directly impacts on us, those close to us and the land in which we live. And even those who boldly put their lives on the line at the behest of politicians (politicians who remain safely on home soil during the conflict, of course) are at least well trained and equipped for the task, and as individuals their lives tend to be valued by their commanders. This wasn't always the way. The First World War remains to this day an object lesson in the senseless and thoughtless waste of human life, a conflict in which ordering whole companies of soldiers to march blindly towards a hail of enemy machine-gun fire was somehow regarded as a valid military tactic. For this very reason, it's still the war with which the term ‘cannon fodder' is most strongly associated.

It's no surprise that the period of peace that followed saw a rise in pacifism, the sort of thinking that would have been deemed traitorous during the war itself, and that this would find impassioned expression in art. In Germany, this was perhaps most famously realised by WW1 veteran Erich Maria Remarque in his best-selling 1929 novel, All Quiet on the Western Front, a work whose realistic description of trench life saw it embraced by pacifists as an anti-war masterpiece, and become one of the first books to be publicly burnt when the Nazis came to power in 1933. As if the book itself wasn't enough to enrage Hitler and his cronies, in 1930 it was made into a Hollywood film by screenwriters Maxwell Anderson, George Abbott and Del Andrews and director Lewis Milestone, a film that was universally praised and became the first film with synchronised sound to win Oscars for Best Film and Best Director. During its brief release in Germany, Nazi goons disrupted screenings by letting off stink bombs, throwing sneezing powder and letting mice loose in the cinemas in which it was screened. It is now widely regarded as one of the all-time great war films and a classic of pacifist cinema.

Less widely discussed is a similarly themed film from the same year by G.W. Pabst, probably for the glumly simple reason that it was made in Germany rather than Hollywood and was the subject of a war-time ban by the German authorities. And before I start sounding like someone who has been championing the film for years to a viewing public that is deaf to my chants, I should freely admit that I knew next to nothing about Westfront 1918 when Eureka's dual format release was first announced. Now that I have seen it and its on-disc companion piece, Kameradschaft, however, I do feel the need to shout the film's many and considerable merits from the highest rooftops, and strongly suggest that it is easily the equal of Milestone's justly celebrated masterwork.

The film opens in the house of French peasant girl Yvette and her ageing father, where a group of German soldiers have been billeted during the later stages of WW1. Yvette cheerfully tolerates the soldiers' flirting and physical manhandling, but has fallen for a young a good-looking recruit known as the Student, who is equally besotted with her. When the company is called back to the front, Yvette begs the Student not to go, but he departs anyway with the sincere promise to return. As the company returns to active duty, the film focusses on the fate of four soldiers – Karl, The Student, a brawny Bavarian, and their company commander, known only as the Lieutenant – as their stories unfold and overlap. When a direct hit on the trenches traps a small group of soldiers in a collapsing dugout, for example, it's the strong Bavarian who buys them a little time by holding up the wooden roof, the level-headed Karl who chastises another soldier for using up their oxygen with a naked flame, and the Student who helps to dig them free. When it emerges that this latest bombardment is the result of their own side's shells falling short, the Lieutenant asks for a volunteer to run across the battlefield to headquarters to alert their commanders. With bombs still raining down around them, no-one steps up, at least until the Student realises that this might offer him the opportunity to pay a visit to Yvette. All he must do is avoid falling victim to enemy fire and his own side's misdirected artillery shells.

And we're just getting started here. In putting the experience and emotions of the four soldiers to the fore, Pabst bonds us with them from an early stage, adding tension to the Bavarian's gritted-teeth efforts to prevent his dugout from collapsing on him and his comrades, and prompting a wince when an explosion knocks the Student off his feet in no-man's land, only to have the camera glide over to reveal that that he has suffered no serious injury and is able to continue. This empathic bond reaches an unexpected peak when Karl is given furlough and heads home to Berlin to visit his wife and finds her in bed with another man (remember for a second the year in which this film was made), a butcher boy from downstairs who himself is due to ship out to the front the following day. There's a whole essay of potential discussion and analysis in these scenes alone, as we are shown that life on the home front has also been negatively impacted by the war, leaving Karl's wife desperate for intimacy and supplies, and his mother having to wait so long for what little food is available that she'll not surrender her place in the queue even when she realises that her son has come home. Karl's secondary response to his grim discovery, meanwhile, is not to attack this interloper or his wife, but point his gun at the couple and angrily order them to kiss, a forced humiliation that he follows through by then ordering the man to leave and continually ignoring his wife's pleas to talk about what has happened, a decision that will later come back to haunt him.

At a time when sound cinema was in its infancy and cameras were bulky and largely immobile, Pabst refused from the off to be confined by these restraints, and instead had improvised blimps created to quieten the camera and shot whole sequences silent and added the soundtrack in editing to allow him to move his camera freely when required. The results are sometimes striking, as we glide for some distance along the side of a trench following the soldiers as they make their way through it, a stylistic choice that strengthens our connection to them as we follow their movements rather than watching from a more observational static viewpoint. This is enhanced by the decision to shoot the trench scenes in an outdoor location rather than recreate them in the studio, building an air of realism as tangible as that of the justly celebrated trench scenes in Kubrick's Paths of Glory. Elsewhere, Pabst takes chances with pacing and content that theoretically shouldn't pay off, notably when a respite from the fighting allows the soldiers to kick back and enjoy a variety of staged comic and musical entertainments. As a sequence, it's allowed to run far longer than is required by the narrative but it proves oddly captivating nonetheless, as we become part of an audience for a trio of surprisingly engaging performers whom Pabst himself appears to be enjoying too much to be willing to interrupt (I was certainly smiling at the high-speed xylophone duet finale).

It's this sometimes-vivid sense of realism that gives the film is longevity, particularly those moments when action is observed statically from what feels like the viewpoint of a war cameraman caught up in a very real battle, as explosions blow holes in the landscape that the resultant debris and smoke then drifts over and engulfs. It's a technique that peaks in a wide shot of the assault that kicks off the fateful climactic battle, which runs uninterrupted for over two minutes of screen time as French soldiers and tanks advance and a number are brought down by enemy fire – in one case a soldier is seen to fall and then a short while later is almost torn asunder by an explosion just a couple of feet away, further enhancing the sense that what you're watching is not staged but very real. This climactic descent into death, despair and madness is where the film delivers its most devastating emotional body blows, and as an audience we're left in no doubt that war destroys everything and everybody that it touches – the theoretical gains of the conflict are never discussed, but the loss to humanity is all too clear. This was and remains innovative, utterly gripping and forward-thinking humanist cinema, an ultimately devastating indictment of war and its destructive effects on the ordinary people who pay the price for its folly, one that humankind has stubbornly and sadly refused to learn from.

We live in seriously shitty times. Seemingly each way you turn, you'll find a story of people negatively judging others by their race or religion and calling for hostile action against them based on little more than "they're different to me." Such preposterous prejudice is a disease from which racism and even wars ultimately grow, conflicts that further legitimise the very prejudice that laid the grounds for them in the first place. Such nationalistic nonsense is at its most patently absurd on the borders of directly adjoining countries, when potential neighbours in the very same district can become enemies based on nothing more than which side of an arbitrarily defined border they were born on.

Such is the case in the unspecified district on the border of Germany and France in G.W. Pabst's 1931 Kameradschaft [Comradeship]. Two mining towns – one French, one German – dig their coal from what is essentially the same mine, in which below-ground walls have been erected to segregate the tunnels when they cross the border. New mining jobs are thin on the ground, and Germans looking for work at the French mine are turned away with the assurance that there aren't even enough jobs for their own people. When a fire in the French mine gets out of control and traps a number of French miners in the tunnels, however, a group of their German counterparts decide to put past prejudices and disagreements behind them and organise a rescue party.

The basics of the plot of Kameradschaft are all there in that summary, but this a film that lives and breathes in its characters and detail. This is not, I should point out, a precursor to the modern disaster movie, and characters are thus not defined by telling little stories about them in the opening third so that we can wring our hands over their fate when disaster strikes. We instead start to recognise individual miners as we catch them in passing and they interact with one another, whether it be the retired French miner who asks the men heading down for their shift to take care of his young grandson, who works alongside them, or the trio of German miners who decide they'll have a night out in a French bar, where a simple disagreement quickly comes close to escalating into all-out racial conflict.

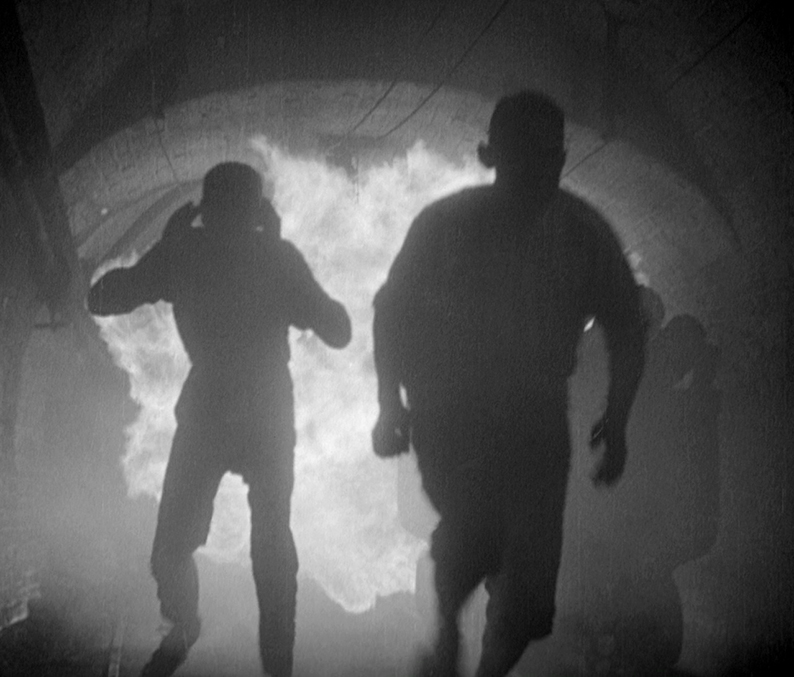

What strikes you once again about the film is how realistic it all feels. Just as Westfront 1918 took us onto what felt like a real battlefield, in Kameradschaft there really is a sense that we're down at the coal face with the miners, even though the underground footage was (most convincingly) created in a studio. This really hits home when the fire takes hold, as flames explode into a clearly roofed tunnel and close enough to the actors (and at one point, the camera) to make me yelp in alarm. Adding to the authentic feel is the lighting camerawork of dual cinematographers Robert Baberske and Fritz Arno Wagner, whose work underground always respects actual light sources and is happy to plunge whole areas into darkness if logic dictates that they would not be lit. This, of course, adds to the claustrophobic nature of the location, both when miners are working the seams and when the rescue teams are climbing through rubble in a search for survivors.

The politics of the situation are deftly handled, with the idea of organising a rescue party coming from German miner Wittkopp and immediately challenged by the prejudices of his co-workers. There's no, Henry V-style rousing call to action, just a heartfelt plea for unity – his passionate justification, "We're all miners," will have a special resonance for those who watched on with despair as whole mining communities wiped out by the Thatcher government – that some respond to and others reject. When they drive headlong through the border crossing and roll up at the French pits, the response from the locals is initially one of disbelief. "Germans," says one astonished woman. "It's incredible." This builds to a finale in which French and German spokesmen alike call for unity and cooperation between their peoples, one so heartfelt I came close to wiping a tear from my eye.

Whereas in Westfront 1918 you were able to tell the French soldiers from the German by the distinctive shapes of their helmets, in Kameradschaft you'll need to have an ear for their respective languages to sometimes know which side of the border we're on or whether we're in the company of French or German miners, who when covered in coal dust are indistinguishable from each other (there's a small lesson about equality and unity right there). Given that there's something like a 50/50 split in the French and English dialogue, I was genuinely astonished to discover, via the introduction on this disc, that the film was originally released in both France and Germany without subtitles, leaving all but the bilingual members of the audience to experience the very communication issues that these two communities struggle to overcome over the course of the story.

Once again, Pabst is technically ahead of the game, moving his camera frequently but always with purpose, locking us in to the emotions, actions or viewpoint of a character or homing in for emphasis, as when the German rescuers first make contact with the trapped miners and the camera moves into frame on a pivotal handshake. Elsewhere, the moving camera enables Pabst to dispense with or drastically shorten whole scenes of character build-up and encourage us instead to make an instant connection. This is perhaps most evident in the scene in which Wittkopp's tearful wife walks with her young child alongside the departing rescue lorries, while her husband tries to convince her of the importance of putting his own life at risk to help people they would once have regarded as their enemy. Shot on the move from their respective viewpoints, it builds a bond between us and the characters in just over a minute of screen time and prompts us to instantly fear for Wittkopp's safety, and does so without recourse to the sort of pre-departure domestic scenes that would be de rigueur in a modern take on the story. Elsewhere there are shots that feel almost as if they've been transported back in time from a later work, as when the backward tracking camera stays locked on to the face of a grimly determined miner as he carries an injured comrade to safety and weakened roof beams come crashing down in his wake. This forward-looking feel is first established in the film's opening scene, in which the two young sons of the respective border guards play a fractious game of marbles – were it not for the French and German dialogue, I could have sworn I was watching an Italian neo-realist film from the 1950s.

The main rescue mission is observed in almost documentary fashion and devoid of personal stories, which instead unfold through the improvised attempts by others to assist in their own way. These include the elderly French ex-miner who uses his guile and his knowledge of the mine's architecture to mount a one-man rescue mission for his missing grandson, and the trio of German drinking buddies, who decide on a whim to join the rescue by breaking through one of the walls that divides the two mines. Elsewhere, one of the German rescue team encounters a French miner who is suffering flashbacks to the war, and instead of welcoming his rescuer, the Frenchman attacks his rescuer under the belief that he is back in the WW1 trenches, a vividly realised hallucination in which sound is as inventively employed as the visuals. And sound is crucial here, as much for how it is used as what not present – as with Westfront 1918, there is no music score to artificially pump up the tension or urgency of the rescue mission.

It depresses the crap out of me that 87 years after this heartfelt plea for international cooperation and comradeship, we as a country are currently in the process of cutting ourselves off from Europe, after a campaign fuelled by false propaganda based on intolerance and the idea that we can only function properly as a country if the society in which we live is populated solely by those who escaped their mothers' wombs on a specific piece of turf. It's thinking like this that leads to the belief that somehow one person could be considered superior to another based solely on the country or even region of their birth, and if you want to know where that ultimately leads, then check your history books and ready your tin helmet. Better still, watch the final few minutes of the film and listen to the passionate speeches of reconciliation, whose words are as relevant now as they ever were, notably when Wittkopp (played by communist actor Ernst Busch, who was doubtless speaking from the heart here) tells a mixed audience of former foes: "Why do we only stick together when we're doing badly? Are we to sit idly by until they fill us with so much hatred that we shoot each other down in another war?" You said it, comrade.

Both films are presented here in their original 1.20:1 aspect ratio and encoded at 1080p on the Blu-ray.

With the original negative lost, Westfront 1918 has been restored by Deutsche Kinemathek in cooperation with the BFI National Archive from a master positive from the BFI National Archive collection, with missing scenes re-inserted from a duplicate negative from Praesens-Film. Taking all that on board, the results of the restoration are genuinely astonishing. Image detail is crisp and the contrast handsomely balanced in daylight scenes, while the night-time trench sequences are appropriately graded, delivering inky black levels and a darkness that required me to wait until evening to clearly follow the action on my plasma TV. An organic level of film grain is visible and while there are faint traces of some former damage, for the most part the picture is strikingly clean. A superb job.

Kameradschaft was filmed in both a French and German version (the differences were apparently minor) and it's the German cut that's presented here. With the original negative and ending of this version now lost, the reconstruction here was based on a dupe positive from the BFI National Archive. A negative of the French version – rather literally titled La Tragédie de la mine – held at the Centre National du Cinéma et de l'Image Animée was sourced for the ending of the film. It's also presented without its original opening titles, which have also been lost and not artificially recreated. Again, the restoration team have done a stunning job, delivering a crisp, clear image with well-balanced contrast and the sort of light-swallowing black levels that the underground sequences absolutely demand. Odd shots here and there are a tad softer than the best material, and while much of the former damage and dirt has been impressively cleaned up, a few visible traces of it do remain. For the most part, however, it's superb.

Both films feature Linear PCM 1.0 mono tracks and both are in good shape for their age. Inevitably, their dynamic range is far narrower than you'll find on a more modern film, with a slightly tinny ring to the dialogue and nothing in the way of punchy bass. But the dialogue is all clear, the all-important sound effects very cleanly rendered (appropriately, the explosions of battle in Westfront 1918 are a lot louder than the dialogue), but there's no obvious damage and surprisingly little background hiss to contend with.

Both films feature optional English subtitles for all dialogue (except, surprisingly, the lyrics of a song sung for the troops in Westfront 1918) that kick in by default. But there's more. As Kameradschaft was originally released in both a French and German version in the respective countries without subtitles (I've briefly discussed this above), Eureka have attempted to recreate this experience by including the option to watch the film with English subtitles for the French or German dialogue only. Cool.

Introduction to Westfront 1918 (17:57)

Jan-Christopher Horak is introduced as a film scholar and expert on G.W. Pabst and both of these badges are clearly well-earned. He delivers a considerable amount of detail on Pabst and Westfront 1918, discussing the film's mix of realist and expressionist elements, the use of tracking shots and how Pabst and his crew bypassed the technical restrictions of working with large and noisy synchronised sound cameras, his determination to make a pacifist film, the positive reception and the later Nazi ban, and more. He also makes some direct comparisons with All Quiet on the Western Front, and in doing so convincingly gives Westfront 1918 the edge. Just one thing, although billed as an introduction, this is in-depth enough in its analysis to be best watched after the film itself. You'll still get plenty from it.

Introduction to Kameradschaft (14:49)

Clearly shot in the same session as the above, Jan-Christopher Horak again delivers some welcome background information on the film and its director, providing information on the character actors who make up the cast, the true-life incident that inspired the story, and the social situation in which the film is set. He also details how Pabst's career faltered once the Nazis came to power, and describes Westfront 1918 and Kameradschaft as the director's two most political films and logical companion pieces. Once again, I'd suggest watching this after rather than before the film itself.

Booklet

The single but substantial essay in this handsomely produced and illustrated booklet is by Philip Kemp and titled Pabst – A Flawed Genius, and looks at Pabst, his career and the two films on this disc, the second of which is criticised for hammering home political points that I firmly believe are worth hammering home. The plots of both are outlined in some detail and there are some major spoilers, so I would definitely save this for after the films themselves. Credits for the film, promotional stills and reproductions of posters are also included.

It's perhaps a tad ironic that two of the finest films I've seen all year were made back at the very start of the sound era and have been sublimely paired on a single Masters of Cinema dual format release. I knew little about either when I popped the disc into my player and I was absolutely blown away by both, for their storytelling, their characters, their striking sense of realism, their remarkable and forward-looking cinematic technique, the passion of their political conviction and so much more. That the extra features are limited to two introductions and a booklet is not an issue when you get two features films of this quality for the price of one, and looking better than they have any right to given their age. Highly and most enthusiastically recommended.

|