|

In a rabbit warren, a young buck called Fiver (voiced by Richard Briers) has an apocalyptic vision. With good reason, as the field is due to be redeveloped. Fiver and his older brother Hazel (John Hurt) plead with the head of the warren Captain Holly (John Bennett) to leave for a safer new home. Holly refuses, but Hazel, Fiver, Bigwig (Michael Graham Cox) and others escape. With the aid of seagull Kehaar (Zero Mostel), they trek across the countryside, but fall foul of the Efrafa warren, led by the tyrannical General Woundwort (Harry Andrews).

Watership Down, written and directed by Martin Rosen from Richard Adams’s bestselling novel, was just the third British-made animated feature to be released, after Animal Farm in 1954 and Yellow Submarine in 1968*. Despite the efforts of the likes of Ralph Bakshi (Fritz the Cat (1972) and others), the template for animation was largely Disney’s, namely that it was a medium for children. That was particularly so if the characters were anthropomorphised animals, as was the case with Rosen’s film and Halas and Batchelor’s take on George Orwell’s novella before it. None of those first three were aimed especially at the young, though they all had family-friendly U certificates. Add to that a number one single, “Bright Eyes” by Art Garfunkel, and the fact that Watership Down was released in October 1978 for the half-term school holidays, and you can see that the misapprehension that this was a kids’ film meant that some rather young children found the film traumatic in its depiction of death and violence. The film has been controversial ever since. It’s on its way to classic status, but a controversial classic at that.

Adams began Watership Down as a series of stories he told to his daughters while driving them to school. They urged him to write them down. Then working as a civil servant, Adams began writing the novel in 1966 and completed it two years later. After several rejections, Rex Collings published it in 1972, when Adams was fifty-two, in a small print run – so if you have an actual first edition, you could probably retire on the proceeds. A second novel, Shardik, followed two years later and Adams became a full-time author. While Watership Down was by some way his most successful novel, commercially and critically, two others were also adapted for cinema: The Plague Dogs, also animated, in 1982 (of which more below), and the decidedly adult and non-animal-related The Girl in a Swing in 1988. Richard Adams died in 2016 at the age of ninety-six.

Much debate has been undertaken as to whether Watership Down is a children’s novel or not. It’s certainly longer (472 pages in the edition I reread the novel in for this review, by my estimate some 150,000 words) and more “literary” than many children’s or young-adult novels before or since would be, but not uniquely so. It was certainly seen as a children’s novel on its publication, winning the Carnegie Medal and the Guardian Children’s Fiction Prize, one of just six novels to win both.** I first read it at ten from the junior school library and, while I was a good reader, I don’t remember having any difficulty in reading it. However, the best writers for children and teenagers have always had adult readers, for example Alan Garner and Ursula Le Guin. So it’s best to say that it, published in both children’s and adult editions, is a novel which crossed over to adults, long before Harry Potter. And cross over it did, becoming a substantial bestseller. Although it takes place in this world – you can visit the real Watership Down, near the Hampshire village of Ecchinswell – it is in many ways a quest fantasy. It includes extensive worldbuilding, with rabbit myths and creation stories, and animal languages, and a narrative evoking Moses (Hazel) leading his followers to a Promised Land. There are even two maps.

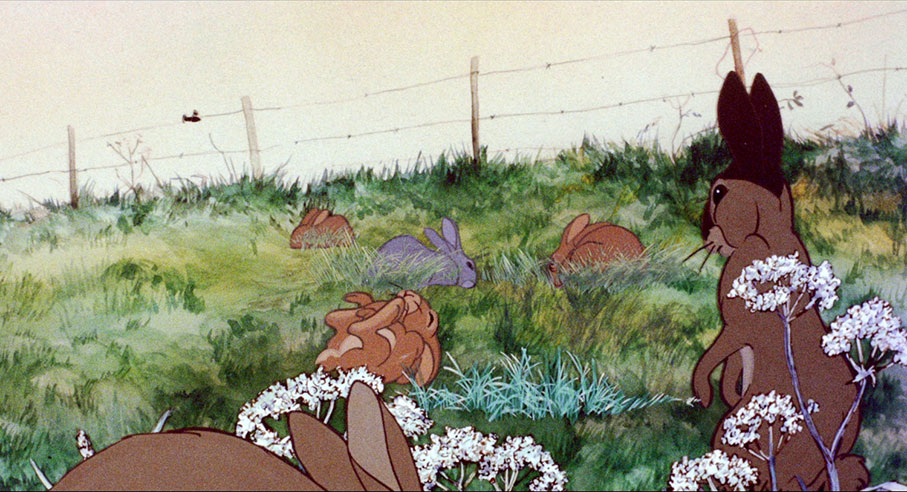

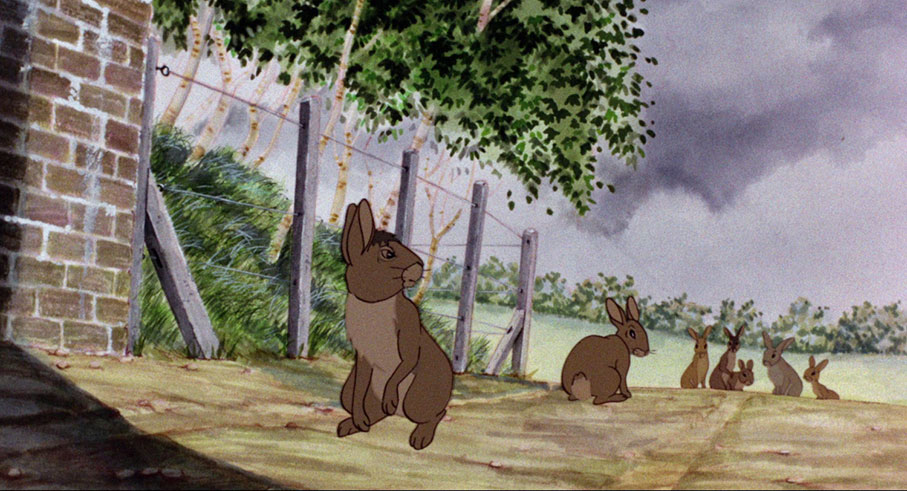

New York-born Martin Rosen was working as a film producer in London – he is credited on Ken Russell’s Women in Love (1969) – when he read the novel. He contacted Adams, who was dubious that his novel was filmable, even as animation, but sold him the rights all the same. Rosen’s screenplay does streamline the novel, no doubt necessary to bring the story in at an hour and a half. Several chapters of the novel detail rabbit mythology, often told as stories by the rabbit Dandelion. Rosen removes most of these, leaving just a prologue before the opening credits. This is a departure in animation style from the rest of the film, designed by Australian Luciana Arrighi and evoking Aboriginal art from her native country. The other major departure in style comes fifty-two minutes in, as Angela Morley’s score leads in to a song written by Mike Batt and sung by Art Garfunkel, “Bright Eyes”. This sequence is more abstract and the changing colours of the rabbits make it almost psychedelic in feel. Extracted from the film to make a promo video, shown on its every appearance on Top of the Pops and elsewhere, “Bright Eyes” reached number one in the UK singles charts on 14 April 1979, and rode the success of the film to stay at the top for six weeks. It was the biggest-selling single in the UK that year. Other than these two sequences, the majority of Watership Down is classic hand-painted animation with a watercolour feel, making much use of a multiplane camera to create the illusion of depth, without actually being 3D.

The original animation director was John Hubley, though due to disagreements with Rosen (apparently about how dark and violent the film should be), he left the production and is uncredited. It’s said that his main mark on the finished film is the prologue, though this is credited to Luciana Arrighi. Another issue involved the film’s music score. This was originally to be provided by Malcolm Williamson, an Australian who was Master of the Queen’s Music from 1975 until he died in 2003. So a recording studio and a full orchestra were expensively booked, only to find that personal problems meant that he had produced only a few minutes of score. Fortunately Jeff Wayne took over the studio and orchestra for his War of the Worlds album, so no money was lost. Rosen replaced Williamson with Angela Morley. She had had a career going back to the 1950s as a composer and arranger (credited pre-gender-transition as Wally Stott), including work for The Goon Show, Hancock’s Half Hour and Powell and Pressburger. She became the first transgender Oscar nominee, twice, for The Little Prince (1975) and The Slipper and the Rose (1978). Her score is a large part of the film’s success, particularly if heard in the new-fangled format of Dolby Stereo. Malcolm Williamson remains on the credits for “incidental music”.

Rosen gathered a distinguished voice cast. They were almost all British, which was in keeping with what Rosen saw as the novel’s Englishness. The major exception was Zero Mostel, who played the seagull Kehaar with an East European accent. (His interpretation is so definitive that it’s disconcerting to watch the 2018 version which has a Scottish seagull, voiced by Peter Capaldi.) Recorded in New York, due to British Equity’s vetoing of Mostel for the role, it was his last work for the cinema, other than his appearance as himself in the Oscar-winning documentary Best Boy (1979). Mostel died in 1977, a year before the film was released.

As mentioned above, Watership Down was released during the school holidays and was given a U certificate. The British Board of Film Censors (as was) deemed that the animation mitigated the effect of the horror and violence on screen – and also overlooked Kehaar’s “Piss off!”, which comes from the novel, to the delight of naughty schoolkids everywhere. However, this decision came back to haunt them, with plenty of younger children being taken to the film and finding it distressing and even scarring. Some people have never watched the film again for that reason. (I didn’t have that experience, but I was fourteen when I saw the film on my own on its first release. Maybe I was made of sterner stuff back then.) Watership Down remains to this day one of the most complained-about films to the BBFC. Even as late as 2016, UK broadcaster Channel 5 received complaints for showing the film in the afternoon on Easter Sunday (“Bunny Bloodbath”, as per the Daily Record). It was finally uprated in 2022 to PG, which is what the film probably ought to have had from the start, or what would have been in 1978 an A certificate.

Following the success of Watership Down, Martin Rosen went on to make a film of Adams’s third novel, The Plague Dogs. This featured many of the cast and crew of Watership Down (with John Hurt again voicing the lead role) and became the fourth British-made animated feature to be released. The story of two dogs who escape from an institute where they had been experimented on, and who may have been infected with bubonic plague, this was far less successful commercially than its predecessor. You can see why: the premise of Watership Down could miss out the fact that the film contains violent and disturbing content, but it’s unavoidable with The Plague Dogs. The film is also even more gory than Watership Down, but attracted less controversy partly due to the fact that the BBFC gave it a well-earned PG certificate, thus making it the first British animated feature film (but not short***) to be rated higher than U, something it shared with the next animated feature made on these shores, When the Wind Blows (1986).

On his commentary on this disc, Martin Rosen says that as he held the rights to the film, he was often approached to give permission for a remake. He generally turned these down, but from 1999 to 2001 there appeared a three-season television series (not seen by me) rather loosely based on the novel. Then, in 2018, the BBC and Netflix joined forces to make another version of the story, in four fifty-minute episodes (shown as two double-length episodes on the BBC), rendered via 3D computer animation. While its greater length does allow more of the novel to be conveyed, it’s less successful than the feature film, with much blander animation. There have also been stage and radio productions of the novel. Dispute about rights between Rosen and the Adams estate caused a release of this Blu-ray and UHD to be cancelled, but now that that has been resolved it is now able to be released. As such, it is very welcome.

Watership Down is released on UHD and Blu-ray by the BFI. This is a review of the film on the latter format, a disc encoded for Region B only. As mentioned above, the film had a U certificate originally but as of 2022 is now a PG. Bolly in A Space Adventure has been passed at U. The other short films on the disc are documentaries exempted from BBFC classification, but Once We Were Four… was a U on its original cinema release.

The film was made in 35mm colour and the transfer is in the intended ratio of 1.85:1. It is derived from a 4K scan of the original negative. The results are first-rate, with the watercolour look I remember from my cinema viewing, and extracts seen since, well in evidence, colourful when it needs to be, with solid blacks.

Watership Down was an early British feature, and the first animated feature, to have a Dolby Stereo soundtrack, though to hear it to its full potential you would have had to see it in one of its showcase cinemas, such as in London. Everywhere else it would have been distributed in mono, as was the case with me in Aldershot in 1978. This sound mix is rendered on this disc as LPCM 2.0, which plays in surround. The surround is used mainly for the music score, but also includes some sound effects, such as rainfall and thunder and there are occasional directional sounds.. There is also an audio-descriptive track in Dolby Digital 2.0 (also surround). English subtitles for the hard of hearing are available for the feature. Excellently, they are available on all the extras except for the commentaries and those with no dialogue or narration, namely Arthur Humberstone’s Super 8 footage and “Designing Watership Down”.

Commentary with Martin Rosen and Chris Gore

This commentary was recorded in 2003 for the twenty-fifth-anniversary DVD release. It’s not really scene-specific even though Gore reveals late on that they are talking as they watch a mute copy of the film. Gore does ask Rosen about the opening sequence as we see it on screen, and it’s likely accidental that Zero Mostel is mentioned just as Kehaar appears. Otherwise, it’s an hour and a half of Gore prompting Rosen with specific questions about the film’s production. Rosen says that most of the voice cast were keen to take part, having either read the novel or doing so when they were approached. An exception was Peter Cook, whom Rosen wanted for a role, but he declined to read the novel and asked for too much money. Zero Mostel would have been put up at the Savoy Hotel in a room overlooking the Thames if Equity hadn’t vetoed him, so Rosen flew to New York and recorded him there. Rosen talks about the difficulties with Malcolm Williamson, which resulted in Angela Morley composing the score. He also speaks about his difficulties finding distributors, and his refusal to let the Americans redub the voice cast. He is proud of a film which was described as somewhere in between Animal Farm, Seven Samurai and the works of Sam Peckinpah. He also says that he has been approached for permission to remake the film, but even with CGI animation now available, he hasn’t seen anything which would add anything new to what he and his team made – though clearly he was persuaded later, as mentioned above. This track doesn’t really come to a close, as Gore continues asking questions as the final credits are on screen, ending with one about Donnie Darko, another rabbit film which at one point was due to license an extract from Watership Down, but that isn’t in the final version.

Commentary with Catherine Lester and Sam Summers

Newly recorded for this release, this track features film and animation scholars Catherine Lester and Sam Summers. As this track, unlike the other one, doesn’t feature anyone actually involved in the film’s production, it’s a discussion from outside and is able to be more scene-specific, beginning with the opening sequence. Lester in particular sees Watership Down as a horror film and there’s much discussion on how its being animated might mitigate the depiction of violence – something the BBFC took into consideration when they originally gave the film a U certificate. Lester does comment on the film’s enlargement of the female characters from the novel, with two or three roles given more agency than they have on the page. In the novel, the does are little more than bargaining chips to drive the plot and the book is pretty much a lapine sausagefest. This was something the 2018 version took further. Both commentaries are well worth listening to, and complement each other well.

A Conversation with the Filmmakers (17:14)

In 2005, Martin Rosen and film/sound editor Terry Rawlings talk about Watership Down. They first met on Women in Love, in which Rawlings was dubbing editor. Rawlings reveals that he spent a few nights on the actual Watership Down recording ambience, which ended up in the film. This was only his second feature as a film editor, but he was soon snapped up: his next film in that capacity was Alien. (He died in 2019, aged eighty-five.) Some of the subjects discussed recur elsewhere in the extras on this release, such as Malcolm Williamson’s dropping out to be replaced at short notice by Angela Morley, and the difficulties in finding distribution.

Defining a Style (12:06)

In which several of the animators, and one voice actor in the shape of Joss Ackland (who is proud to show the film to his grandchildren – he had thirty-one of them), also in 2005, get to talk about their work on Watership Down. This is more anecdotal than nuts-and-bolts stuff, and it’s clear that several of these men have worked together more than once and know each other well. Some of them went from London for Watership Down to the States to work on The Plague Dogs. John Hurt visited the office and made a comment about the building being a rabbit warren – you bet they’d heard that one before. Even if the building was in Warren Street.

Storyboard comparisons (14:06)

Four sequences from the film, with the appropriate storyboards inserted into the bottom right-hand corner. They are “Opening Sequence” (3:47), “Nuthanger Farm” (4:33), “Hazel is Injured” (2:39) and “Efrafa Chase” (3:04), with a Play All option.

Super 8 version (28:14)

Before the coming of home video, the nearest to home cinema many households were able to be was in versions of films released on the consumer medium of Super 8mm film. These were cut-down edits of the features, here to just under a third of the full length, in 4:3 and mono sound with noticeably lower-fi picture quality. But that was the only way most people could come anywhere near to replicating the theatrical experience in their living rooms, especially as the means of recording films from television broadcast and watching or rewatching them later was beyond all but the rich at the time.

Nepenthe Super 8 footage (2:54)

Shot by senior animator Arthur Humberstone, who puts himself in shot right at the start, this takes us round the London premises of Nepenthe, the film’s production company. It is presented silent with music, and there are captions identifying Humberstone and other members of the crew.

Designing Watership Down (4:17)

More from Arthur Humberstone, whose career, who worked on all four of the first four animated features made in the UK and also the 1989 version of Roald Dahl’s The BFG. This item, silent with a music score, is a gallery of materials of his from Watership Down.

Trailers and TV spots (6:14)

With a Play All option, we have the original trailer (3:42), the reissue trailer (1:29) and two American TV spots (0:31 and 0:30). As those times indicate, you sense that in 1978 that the marketing department didn’t quite know how to sell this, given the rather lengthy runtime. Come 2024, its success now a done deal, the trailer is much shorter and we can now have quotes from the great and good, namely Guillermo del Toro, Andrew Haigh and someone from The Independent. There are US critics’ quotes on the two TV spots as well.

Treasures from the BFI National Archive (47:35)

As often with a BFI release, here are some short items from the archive which don’t reflect directly on the main feature itself but are tangential to some of its themes. Here that means rabbits, rabbits and more rabbits. All are presented in 1.37:1 with LPCM 1.0 sound, the middle two in colour and the first and last in black and white. There is a Play All option.

Once We Were Four… (8:50)

From a series called Secrets of Life, Once We Were Four… dates from 1942. It’s directed by Mary Field, who was a significant figure in UK documentary film history. Her career went back to silent days and she appeared on the nascent medium of television before the War. After the War, she was instrumental in setting up what became the Children’s Film Foundation, source of many a BFI release and/or extra up to now. Apparently no fan of what passed as film entertainment at the time, particularly if it came from America, she seemed to be driven by an urge to improve and educate, the young in particular, but that didn’t get in the way of her directing abilities nor her ability to entertain. That was however idiosyncratic and at times positively strange. The jolly narration of regular newsreel commentator E.V.H, Emmett doesn’t really prepare us for a German bomber dropping its load on the fluffy bunnies we’ve been watching until now. But, as with her onetime collaborator F. Percy Smith, there’s a real eye at work.

Rabbits or Profits (15:45)

Made in 1969 for a combination of the Central Office of Information, Fisheries and Food and the Ministry of Agriculture, this item talks about rabbits not as cute little fluffy bunnies but a potential menace to the livelihoods of the farming communities, not least because of their ability to breed like...well, rabbits. A bit of history: the rabbit originated in Europe and were most likely introduced to Britain by the Normans, often used for food. But fear not, the best way to rid your land of them is to shoot them (take heed of your gun safety lessons though – something Rosen picked up on in the film of The Plague Dogs, though involving a dog rather than a rabbit). The alternatives include snares, traps, ferrets and the administration of cyanide. Remember, in 1969, lapine predation of your crops and grasses cost you “a quid a head a year” and there were sixty million of the creatures. A decade and a half earlier, myxomatosis didn’t do the job, and the 1954 Pests Act gave farmers an obligation to clear their land of legally-defined vermin.

Bolly in A Space Adventure (5:10)

Bolly may not be a rabbit but he has such a tail, as well as a mouse’s ears and a human’s face. Oh and he’s coloured red, so that’s some evolution in progress where he came from. He lives in a giant mushroom and he has a close encounter of the third kind thanks to a passing flying saucer. This short was made in 1968 by the long-standing animation house of Halas and Batchelor, with Joy Batchelor writing, producing, directing and providing the song lyrics here. (The music is provided by Keith Potger and David Groom from The New Seekers.) It’s all very charming. The title suggests that this was the first of a possible franchise, but it was the only one made.

Cartoonland: A Novelty Adventure (17:40)

On the menu and in the book as Cartoonland: Make Believe, but the on-screen title is as above. This is from 1948 and shows us behind the scenes at Anson Dyer studio, which is where Watership Down’s animation director Tony Guy had his start. In fact Dyer appears at the start, his young niece (billed as Christine Anne) on his knee and telling her uncle she doesn’t believe in fairy stories. Hence the adventures of Ronnie Rabbit, who gets an “introducing” credit. And then we move on to Dyer’s studio where he and his animators meet to discuss Ronnie’s next adventure, and we see them at work on it. Without the uncle/niece bookends, this could have been a disc extra if the only discs around in 1948 weren’t made of shellac and used to play music.

Book

The BFI’s perfect-bound book, available in the first pressing of this release, runs to seventy-six pages plus covers. It begins, after a spoiler warning, with an essay by Jez Stewart. This begins with a discussion of the press coverage before the film’s release, which promised something rather cuddlier than what actually appeared. But as, Stewart points out, any kind of animation in the UK was less than usual, and the Disney template was what prevailed. However, this film, and the two previous British-made animated features, were not primarily aimed at children, even they all did have kid-friendly U certificates. This follows with an account of Martin Rosen’s entry into the industry and his reading of Richard Adams’s novel, after which he contacted the man himself. The article gives an overview of the production, including the falling-out with original animation director John Hubley and Malcolm Williamson’s short-notice replacement by Angela Morley. Stewart goes on to discuss the film’s release and gives a brief mention to Rosen’s next Adams adaptation, The Plague Dogs.

After a two-page crew and cast listing, Catherine Lester contributes “Rabbits and Children: Approach with Caution”. She begins by addressing whether the film was ever intended for children, though most parents missed the fact that Bigwig’s picture on the poster has his neck caught in a snare. She goes on to discuss rabbits in popular culture, rarely seen in children’s fantasy especially as anything other than cute and fluffy: see Alice’s guide the White Rabbit and Beatrix Potter’s various characters. They can be childhood companions (such as in Ann Turner’s film Celia, 1989) or meet sticky ends, notoriously in Fatal Attraction (1987). At least Watership Down has a large number of characters, so rabbit diversity in abundance. Adams studied rabbit behaviour while writing his novel, and Rosen’s animators took much note of their movements. But the prevailing cutesiness explains the reactions when young children in particular encounter this film for the first time.

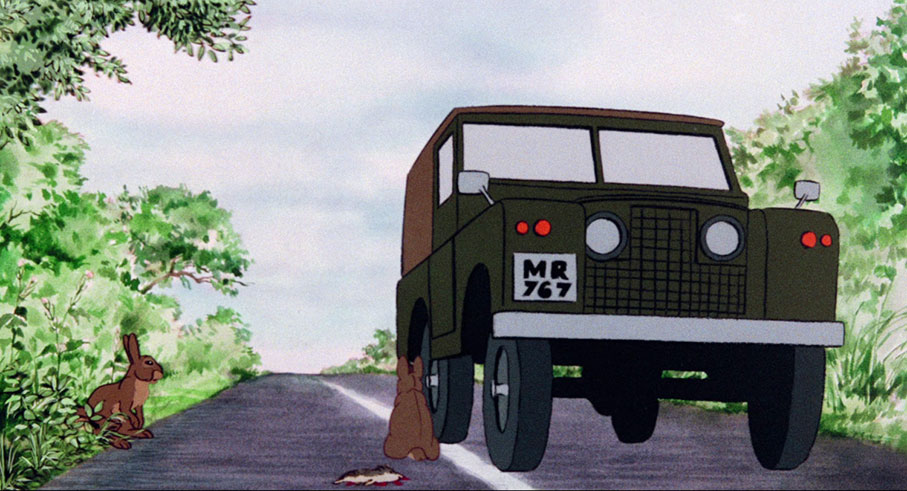

Caroline Millar contributes “Kinship and Cocoa: Watching Watership Down in the Anthropocene”. Millar first saw the film on VHS in 1985 on a school trip, and it appeared to have had quite an effect on many of the children. Nowadays, she is more disconcerted by the brief appearances of the humans, and the revelation to us (but not the rabbits, who presumably can’t read) of what the threat is: a housing development. From an environmental viewpoint, this sets off alarm bells which might not have been struck to an extent when the novel was first published and the film first released.

“‘My Heart Has Joined the Thousand, for My Friend Stopped Running Today’” by Tim Coleman examines Watership Down from a different perspective, that of the five stages of grief as identified in 1969 by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross. These are denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance, and Coleman relates the film’s plot to each of these in turn.

Arthur Humberstone is up next, in the shape of a profile by his musician sons Nigel and Klive. Reproduced in this are several samples of their father’s work as preserved in his archive. He seems to have kept virtually everything, including charts and progress reports, even when asked to destroy them once a production had finished. His involvement with Watership Down came when he submitted drawings on spec to Martin Rosen. He met with Rosen and John Hubley and began work the same day alongside Phil Duncan, who went back even further than he had, having worked for Disney on Bambi (1942). Humberstone even kept twenty-six rabbits at home during the production, filming them on Super 8 to observe their movements, though those films aren’t on this disc. He did likewise with his own dog, which helped for the scene where the farmer’s dog walked along a riverbank. The Humberstones are looking for funding to enable their father’s archive to be digitised.

The late Angela Morley follows, with “How the Music Score for Watership Down Came Together”, reprinted from her website. She describes how she first became aware of the film, and the circumstances of Malcolm Williamson’s being unable to complete his score. Williamson had composed two sketches: the background to the prologue and the woodwind-and-strings 7/8-time main theme. She and orchestrator Larry Ashmore arranged and recorded these two pieces. After that Morley was asked to complete the score, which she agreed to hesitantly as she hadn’t read the novel. However, she was shown a version of the film. Most of the themes for the characters had English pastoral inspiration, but Kehaar’s was a Viennese waltz featuring an alto saxophone. In all, she composed fifty-one and a half minutes of music for a film which runs ninety-two. “Kehaar’s Theme” was the B-side to “Bright Eyes”, so must have done very well for her given that record’s success.

More on a musical theme with “Is It a Kind of Dream? Creating Bright Eyes”, by Charlie Brigden, which points out that this languid melody plays out in the film as Hazel fights to live after being wounded. Mike Batt had been behind quite a few hit singles and was one of several noted session players inside Womble suits for their series of bangers in the mid 1970s. That let to his only previous film work, Wombling Free (1977). Art Garfunkel was always the first choice to sing his song about death, but Colin Blunstone of The Zombies was the back-up in case Garfunkel didn’t work out. However, Garfunkel accepted in three days. Rendered uncool because of his work with The Wombles, Batt said that “Bright Eyes” made many people reconsider or, as he says, “maybe [he] isn’t quite such a twat as we thought he was”.

On from the music to the source material. Lillian Crawford contributes “Richard Adams: The Man Who Simply Saw Rabbits”, as it suggests, a profile of the man himself. Adams had no involvement in the film of his first novel and saw them as separate entities: they were Martin Rosen’s rabbits, not his. He also denied any allegorical intention, unlike say George Orwell in Animal Farm, though Crawford says that it’s not hard to see more in his work than he seems to have done, or admitted to have done. Crawford describes the literariness of Adams’s style, drawing on Greek epics, Shakespeare and Walter de la Mare, who provides the epigraph to the novel. (Each chapter has its own epigraph too.) Crawford also discusses the limited roles for female rabbits, something Adams later addressed in his 1996 book Tales from Watership Down.

Also in the book are notes on and credits for the special features. The notes on the short films are extended pieces: Vic Pratt on Once We Were Four…, Tony Dykes on Rabbits or Profits and Michael Brooke on Bolly in A Space Adventure and Cartoonland.

Also included with this limited edition are a double-sided poster with the original 1978 and the 2024 reissue artwork, and four postcards featuring images and sketches from the film, neither supplied for review.

A commercially successful film version of a bestselling novel, Watership Down has been well regarded since its release in 1978, if you didn’t find it too traumatic to revisit. It’s well presented on this BFI release, and as ever if you have any interest (in animation or film music particularly) then buy it early enough to get the book, which adds considerable value in itself.

* These were preceded by the silent animated feature The Story of the Flag (1927), made by Anson Dyer. However, this doesn’t count as the producer had doubts as to the commerciality of a feature-length animation (about an hour long) so it was released as six shorts. It is now a lost film.

** The others are Alan Garner’s The Owl Service, Geraldine McCaughrean’s A Pack of Lies, Anne Fine’s Goggle-Eyes, Philip Pullman’s Northern Lights (aka The Golden Compass, volume one of the His Dark Materials trilogy) and Melvin Burgess’s Junk. Some all-time classics there, all bar A Pack of Lies having been adapted for film or television.

*** See for example Bob Godfrey’s amusing skit Kama Sutra Rides Again, passed with a AA certificate (restricted to those fourteen and over) in 1971, David Grant’s Sinderella (passed X – eighteen and over – in 1973 after having been previously rejected) and Grant’s Snow White and the Seven Perverts aka Some Day My Prince Will Come (rejected in 1973 and passed X with cuts in 1977). For the record, the first animated film passed X (then sixteen and over) by the BBFC was the eight-minute 1953 American adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Tell-Tale Heart, narrated by James Mason.

|