|

If you're looking for an introduction to the work of Polish animator and filmmaker Walerian Borowczyk, you can do no better than the extraordinary collection under review here. Headlined by Borowczyk's first feature, Theatre of Mr. and Mrs. Kabal, the disc also includes twelve of his short films and three of his commercials, all of which are technically short films as well. All this is supported by a solid documentary on the director's short film work at Les Cinéastes Associés and a brief but busy trip through his graphic artwork. By the time you've watched everything on offer here you should have a solid grounding in Borowczyk's considerable talent as an artist, animator, humourist, surrealist, social commentator, live action director, sound designer, and avant-garde experimentalist. I've probably missed a couple.

I've got a lot of Borowczyk to watch and write about in the coming week, so I'm going to cut my usual preamble about how I (eventually) came to his work, in part because I've already covered it in my recent blog on the subject, some of which has been unconsciously lifted almost word-for-word from the intro to my interview with disc producer and Borowczyk evangelist Daniel Bird. All five of the dual-format discs in this collection have also been released together as part of a beautifully produced limited edition box set, but word has it that every copy has already been sold on pre-order. It thus makes more sense for me to cover each of the discs individually, as all five are also to be released as stand-alone dual-format editions. Working chronologically, Walerian Borowczyk Short Films and Animation is the first, and also contains the largest number of individual titles. To avoid losing my audience I'm attempting to keep my coverage of each of them brief. Well, most of them anyway.

The order in which you watch the films is completely down to you, but if you're new to Borowczyk's early work – and I certainly was – then I'd suggest going against my usual advice and heading straight to the extra features and watching the documentary, Film is Not a Sausage (trust me, the title makes sense when you see it). This provides a useful introduction to Borowczyk and his work and includes enticing clips of the films that you can then watch in full. Personally I'd also save the feature for last, as by then you'll have seen the short film that inspired it and have a better appreciation of the director's sense of humour and unique and sometimes unpredictable style. Which order you watch the short films is also not as obvious as it may seem. You can select them individually and watch them in chronological order, as I did, but if you select 'Play Programme' from the menu, you are informed that Borowczyk never intended that the film be viewed that way, and instead you get a running order copiled in collaboration with Borowczyk's assistant Dominique Duvergé-Ségrétin.

Having said all that, I'm now going to stick to review tradition and deal with the films and features in the order they appear on the pleasingly sparse menus of this Blu-ray disc.

| Theatre of Mr. and Mrs. Kabal (1967 – 77:05) |

|

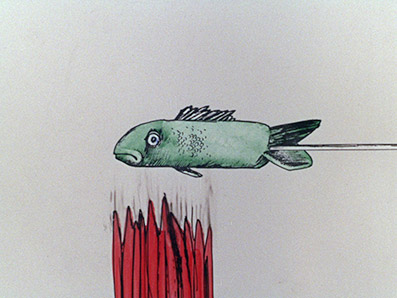

This may sound a little woolly and evasive, but it's hard to know where to start with a film like Theatre of Mr. and Mrs. Kabal [Théâtre de Monsieur & Madame Kabal]. It's not that I'm new to surrealist cinema or even surrealistic animated features, but in some respects this is surrealist film in its purest form. Like Buñuel and Dali's ground-breaking 1929 short Un Chien Andalou, there is no overriding plot to hang your appreciation on, and thus no immediately obvious subtext to analyse and debate. So what is it that makes Theatre of Mr. and Mrs. Kabal such oddly compulsive viewing?

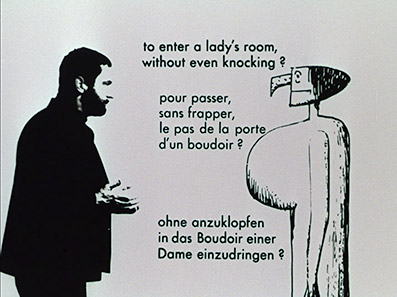

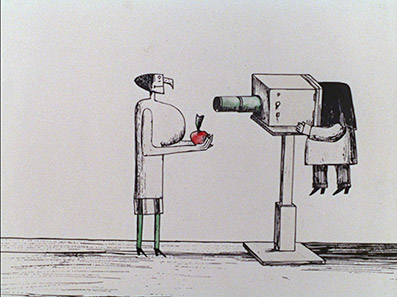

If you followed my above advice and watched the short films in this set before the main feature, you'll already be familiar with the titular lead characters, who are physically mismatched in that way that interesting couples often are in real life. Mrs. Kabal is tall, huge breasted, lanky legged and bird faced, and she walks slowly in loud and mechanical steps. Mr. Kabal is short, rotund, has small stumpy legs and runs around like a mouse on a cocaine binge. They live in a house located slap bang in the middle of a colourless and largely featureless landscape, sharing space with pets that might just be two dogs and a pig but probably aren't. And a wriggly worm. And there are butterflies everywhere and they get into everything, including at one point Mrs. Kabal. I'll get to that in a minute.

In a seductive piece of pre-postmodernist fourth wall breaking, the opening scene consists of an attempt to sketch Mrs. Kabal that is repeatedly frustrated when the artist cannot seem to draw an appropriate head. When he finally gets it right, a lithographic version of Borowczyk himself walks on and explains to his creation – who talks in a series of abbreviated beeps – what he'd like her to do for the next eighty minutes. The film then observes Mrs. Kabal and her husband as they go about their day, but their day is not like any I can readily recall, with familiar and even everyday activities like preparing a meal or a trip to the seaside transformed into episodes from a messed up dream. Throwaway moments – Mr. Kabal on his back bouncing a beach ball on his fingers, or his wife squashing butterflies that land on her back – are extended and lingered on for far longer than a story-led film would require. But these sequences often develop an odd audio-visual poetry, as when individual butterflies momentarily collide with the discarded beach ball and tap and flutter out a strangely entrancing series of hollow metallic notes.

As the film progresses, the sources of the often entertaining abstraction become easier to appreciate, with caring for a loved one and medicating a disease represented here by Mr. Kabal entering the inflated body of Mrs. Kabal and chasing down two of those pesky butterflies under direction of his wife's severed head. With the treatment administered, she's quickly back on her feet and replacing her head with a new one from a box like a freshly purchased hat. And despite my earlier claim about unobvious subtext, it's hard not to read some political intent in the scene in which Mrs. Kabal embarks on a programme of munitions production, then uses the shells to blow up her house, only to have the butterflies collect all the pieces and reconstruct the home as it was before this excessive and pointless destruction.

A number of elements appear to be down largely to Borowczyk's sense of surrealistic fun, notably the live action inserts of bikini-clad girls and their angry male suitor that Mr. Kabal repeatedly and eagerly spies through his binoculars. This idea that an animated character is able to see past his own two-dimensional existence and into the real world is echoed when he finds himself surrounded by live-action lions, and at one point the animated Mr. Kabal shoots an arrow that crosses into the live action world and takes the hat off the head of the bikini girls' suitor. There's even a gag that that works by providing us only with the sound to something that Mrs. Kabal is watching and letting it run long enough for us to assume that the noise has no logical explanation, and then providing one. The punch line to this made me laugh out loud.

I could rattle on endlessly about individual scenes and how they play out and how they could be interpreted, but it will mean very little unless you already know the film, so uniquely and entrancingly oddball is Borowczyk's handling. Indeed, I'd go as far as to suggest that the film's strangeness is a key aspect of it's appeal, and if that statement makes no sense then I'm fairly certain that this is not the film for you. The technique alone is a source of fascination, from the carefully crafted crudity of the line drawn artwork to the consistently extraordinary use of sound – this is, in a very literal meaning of the term, every inch an audio-visual experience. Challenging in the way that all important art should be but oddly charming at one and the same time, Theatre of Mr. and Mrs. Kabal remains, despite a detectable influence on later animators, a unique and peculiarly rewarding experience. It will likely infuriate as many as it delights, but if you do fall for its charms then the chances are you won't be able to get it out of your head, so keep the disc handy for follow-up viewings.

The Astronauts (1959) (12:37)

One of Borowczyk's most celebrated early short films follows the adventures of a do-it-yourself astronaut, whose first move after constructing his cardboard spaceship is to use it to spy on a girl in a state of partial undress. Blending animated photographs with engravings and paintings, it's a sprightly, comical and inventive work with a surrealistic edge and a dash of the space race politics to come, and makes terrific use of sound effects and music. An influence on the work of Belgian animator Raoul Servais (Harpya) is certainly evident here. Chris Marker is credited for a role that he later claimed involved little work on his behalf – he agreed to let his name be put on the film because as a Polish national, Borowczyk would not be granted his first director credit without it.

The Concert (1962) (7:01)

The first appearance of Mr. and Mrs. Kabal is a blackly comic piece in which a piano recital by Mrs. Kabal takes a dark turn when her husband foolishly snores through her performance. The design of the couple as they appear in the feature is fully in place here, and the cut-out style of the animation is a delight. As with the feature, the use of sound is an essential part of the film's fabric.

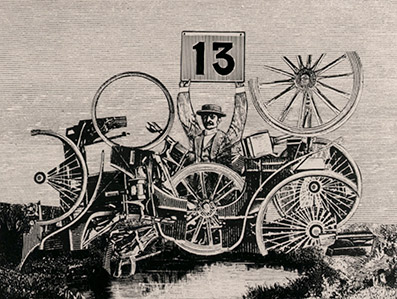

Grandma's Encyclopaedia (1963) (6:51)

Cut-outs and etchings are employed to joyously bring to life three modes of transport from the encyclopaedia of the title – Automobile, Balloon and Railway. Automobile consists of a manically paced vintage car race, while Railway economically compresses the development of the railways as a mode of transporting people, livestock and goods into a couple of minutes of waste-free screen time. It ends with the promise of more volumes to come, but as far as I'm aware these never appeared.

Renaissance (1963) (9:18)

The destruction of a room and its contents undergoes a process of gradual reversal in a beautifully devised and animated work that just has to have been an influence on the work of Jan Svankmajer and the Brothers Quay – it even features one of those creepy dolls with the top of its head missing that the Quays are so fond of. The use of sound effects is once again remarkable and sometimes unexpected, with the clack of typewriter keys accompanying the staccato regrowth of grapes on a previously dead vine. Just superb.

Angels' Games (1964) (12:01)

Angels are dismembered and recreated in a grim and featureless factory in a semi-abstract and surrealistic allegory of Nazi concentration camps and Soviet post-war industrialisation. Deeply unsettling in its suggestion and dark atmosphere, and with an extraordinary impressionist opening train ride, it again makes evocative use of sound effects and music.

Joachim's Dictionary (1965) (9:26)

Twenty-six dictionary words, one for each letter of the alphabet, are illustrated using the same simple drawing of a man, one based on a design by Laurence Demaria (actually Ligia Browczyk, the director's wife). Borowczyk has some real fun with this, with 'Realism' represented by the appearance on the figure of a meticulously drawn ear (and a clearly recorded sound for it to listen to), and 'Marriage' by the figure saying simply, "No, I refuse." The fact that the action used to illustrate 'Man' is exactly the same as the one used for 'Boy' will doubtless prompt a nod of agreement from female viewers.

Rosalie (1966) (15:07)

Based on Rosalie Prudent by Guy de Maupassant, this is the story of a maid who, having kept her pregnancy secret from her employers, gave birth without their knowledge and killed and buried the baby. In this haunting, Silver Bear winning live action short, these events are recalled by Rosalie herself from the dock at her trial. Emotionally performed in a single unwavering mid shot by Borowczyk's wife Ligia against a plain white background, her tale is underscored by a superb use of one-second cutaways of objects that have been presented as evidence, including the cloth-wrapped body of her child. At one point the exposure is lightened to the point where it almost isolates Rosalie's head in a frame of pure white, giving her an spellbinding angelic quality.

Gavotte (1967) (10:41)

At a harpsichord performance somewhere in 18th century France, a bored and costumed dwarf has his attempts to find somewhere comfortable to sit repeatedly frustrated, often by a mischievous second dwarf. Playing out in real time at a single location, this intermittently feels like a costumed circus clown routine, but it is rather funny and it looks and sounds lovely in its restored form. It's photographed head on against a wall in a manner that would become something of a Borowczyk visual trademark.

Diptych (1967) (8:41)

As the title suggests, this is a film of two distinct and very different halves, or panels as they are labelled here in reference to the title. The first is a documentary piece that observes a typical morning for Leon Boyer, who despite being almost 100 years old still farms the land, drives a vintage car, and plays with his two dogs. In the second panel we are invited to appreciate the colour and form of cut flowers and a small fluffy kitten to the accompaniment of the musical piece Nadir's Romance. Almost a gallery work that appears to be largely about oppositions, signalled by the stark difference between the steely monochrome and natural sound of the first panel and the vibrant Eastmancolor and composed music of the second. Even two viewings in, I was left with the sense that the up-front symbolism is exactly what it purports to be and that deeper meanings are being left for the viewer to provide. Intriguing nonetheless, and it's hard to believe that the sprightly Boyer is almost as old as the vines that he harvests.

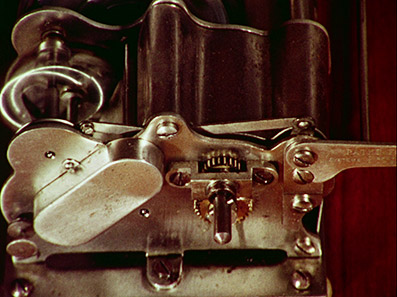

The Phonograph (1969) (5:41)

Wax cylinders make their way onto an antique phonograph, which winds up and plays them in precision-framed stop-motion. The camera lingers on aspects of the mechanism like an eager engineering student, and repeatedly returns to the portrait of a young girl that is hanging on the wall, who may or may not be the audience for the music. Towards the end a socio-political strand is weaved in as La Marseillaise is gradually drowned out by military fanfares and gunfire, and the portrait and wax discs are rapidly destroyed. I'll bet Jan Švankmajer loved this one.

The Greatest Love of All Time (1978) (9:38)

An impressionist portrait of Serbian born French surrealist painter Ljubomir Popović, known more widely as Ljuba, who is observed in the street and working in his studio, sometimes in macro close-up. Very much a film made by an artist about one of his peers, there's an intimacy and subtle reverence here that is quietly intoxicating, and despite the lack of commentary and natural sound (the music of Richard Wagner washes over the soundtrack), we learn a surprising amount about Ljuba's working methods and technique.

Scherzo Infernal (1984) (5:14)

Definitely not one for the prudes or the religiously devout. When a beautiful young angel named Puréa comes of age, she shocks her heavenly father by revealing that she wishes to become a prostitute. Down in Hell, meanwhile, a young devil named Mastro can't quite get the hang of how to torture humans without killing them all off. What do you think might happen if these two were to meet? Sexually explicit and energetically paced and animated, the artwork is delicious, with the clean lines of Heaven giving way to the rough edged splashes of the fires of Hell.

We all try to avoid repeating ourselves, but having taken a look at all five of Arrow Academy's Borowczyk Blu-ray discs, I have the feeling that this section is going to read almost the same on each, so high is the standard across the board. Having said that, the sparse and often monochrome lines of Theatre of Mr. and Mrs. Kabal are probably not the ideal measuring stick for the quality of the restoration work. For that you need an Eastmancolor live action film like Gavotte, which looks absolutely lovely here, from its rich colour rendition to its pitch-perfect contrast and a quite delicious level of detail. My fondness for how wonderful monochrome film can look on Blu-ray was satiated to the point of overload by the transfers on Renaissance and Rosalie, both of which display a grey scale beauty and pin-sharp precision that feel almost real enough to reach out and touch. All of the films are in impressive condition and a few are close to immaculate, with only occasional traces of previous damage (there is some visible flickering on Joachim's Dictionary, for example, but not enought to worry about), and a clarity and stability that belies their age and the condition that some of them were apparently once in. Grain does vary, and is at its most prominent on The Greatest Love of All Time, which was very likely shot on high speed stock.

I may have been dazzled by the quality of some of the images but the PCM Linear mono soundtracks genuinely knocked me for six. It's perhaps a testament to the high standard of Borowczyk's original sound recording and mixing, but the clarity and dynamic range of the soundtracks here beggars belief for films of their age and once damaged condition. And this is so important here. As you've probably picked up from the comments above, the thrillingly creative use of sound effects and music is paramount to all of these films, and to hear those soundtracks so clearly and cleanly reproduced allows us to better appreciate Borowczyk's artistry and intentions.

Introduction by Terry Gilliam (2013) (1:04)

In what feels like and probably are brief snippets from a longer interview (given the date and the point on which it concludes, this was quite possibly recorded to support the initial Kickstarter campaign that funded these restorations), Gilliam talks about Borowczyk's use of sound and the importance of restoring his films.

Film is Not a Sausage (2014) (28:21)

Directed by Daniel Bird, this wonderfully titled documentary explores Borowczyk's short films through interviews with three of his former co-workers at Les Cinéastes Associés in France. It makes for an excellent introduction to the filmmaker's early work, and includes an interview with Borowczyk himself about his 1984 Scherzo Infernal and enough enticing clips from his short films to make you want to dive straight in and watch them. Handy that they're on this disc as well, then. The interviews are peppered with engaging stories (I particularly liked the unexpected claim that when Borowczyk first joined the studio he just didn't fit in), and there's a rather nice anecdote about the theft and reappearance of a life-sized model of Mrs. Kabal.

Blow Ups (2014) (4:43)

A brisk but educational trip through some of Borowczyk's drawings, paintings and poster work, much from his early days as a graphic artist, but including examples from late in his career.

Commercials:

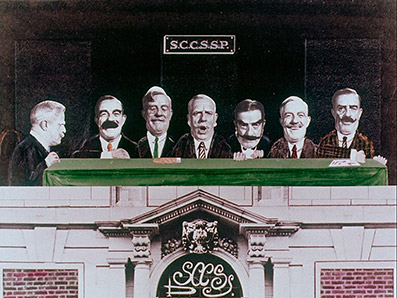

Holy Smoke! (1963) (9:55)

The influence Borowczyk's animated shorts on Terry Gilliam's work for Monty Python is written on every frame of this immensely witty and intermittently hilarious poke at the archaic pomposity of the English upper class, a group of whom have formed The Society for the Conservation of Cigar Smoking for the Specially Privileged. Not quite sure what it's meant to be a commercial for, but I'm buying it anyway.

The Museum (1964) (1:50)

A delightful live action commercial in which a group of amusingly sketched art gallery visitors depart for the evening and the curator serves delicious French pasta for two of the portraits, who lick their lips in eager anticipation. Actually made me hungry.

Tom Thumb (1964) (1:50)

Drawn in the style of woodcut etchings, this second commercial for French pasta (now I'm really getting hungry) is every bit as smart and entertaining as the first. Have to say that the story is more Hansel and Gretel than Tom Thumb – either way, expectations are amusingly inverted by the punch line of the piece.

Booklet

The stand-alone dual format release comes with an excellent booklet containing essays on the films. These include: The Magician: Borowczyk's Short Films, a comprehensive and fact-based (though uncredited) introduction to the films included in this set; Two Films by Walerian Borowczyk by Peter Graham, which examines Renaissance and Angels' Games; a revealing Director's Statement by Borowczyk on Theatre of Mr. and Mrs. Kabal; an essay on Theatre of Mr. and Mrs. Kabal by Daniel Bird tellingly entitled Scratched Into the Screen With a Blunt Fork; intriguing extracts from contemporary reviews of the Mr. and Mrs. Kabal; So Common, Yet So Uncanny, an appreciation of Theatre of Mr. and Mrs. Kabal by respected French director (and second assistant on Borowczyk's Blanche). Also included is detailed information on the restorations, including the specifics of the materials that each of the films were restored from, and even the aspect ratios of specific films. Credits for all of the films (except the commercials) are also provided, and the text is peppered with still from Mr. and Mrs. Kabal and of Borowczyk himself. A superb companion to the film.

Not an on-disc extra, but welcome nonetheless is the option to reverse the disc sleeve to adorn the box with Borowczyk's poster of Theatre of Mr. and Mrs. Kabal. I've already done mine.

Oh, the vagaries of chance. When the Kickstarter campaign to restore Borowczyk's Goto: Isle of Love was launched back in November 2013, I'm sure none of those involved in the project expected such a rapid and enthusiastic response. The funds that were raised easily exceeded their target, and as a result they were able to restore not only Goto, but the collection of films that has been included here. And what a collection it is, fifteen varied but extraordinary short films and an animated feature of the like you'll probably never have seen. It's a glorious introduction to the work of a too often forgotten master of world cinema and one of the twentieth century's most talented and influential animators, all beautifully restored and presented by Arrow as part of the prestige Arrow Academy label. Frankly, I cannot recommend it highly enough.

|