|

– Part 1: The Films –

The second Universal Noir box set from Indicator again consists of six films made in the heyday of noir, though whether they all qualify as noir movies in their own right will likely be in the eye of the individual cinema devotee. I would argue that some of them do not, but that each has elements that are the very least noir-influenced or have scenes that are noirish in their feel or tone. Then again, each has a ‘film noir’ badge on the genre section of their respective IMDb pages, so what do I know? Pleasingly, women play a larger role here than in many genre works, and not just as nominal femme fatale figures, though you’ll still find plenty of examples of 1940s patriarchal attitudes at play here.

A small warning. As is often the case of late, I do get a little carried away with my plot descriptions, though I have tended to constrain myself to the first third of each title, where the main story is still effectively being set up and the characters established. Those who like to know as little about a film as possible before watching it, however, might do well to stick to the final paragraph of my coverage of each film until after watching them to minimise what some might still regard as spoilers. On the subject of spoilers, there is one that I could not really avoid in my coverage of Singapore, but the paragraph in question is preceded by a warning and a clickable link to automatically skip past it if you so wish.

While I do sometimes enjoy going into films completely cold, if you’re planning to watch the films in this box set in chronological order, it’s probably worth knowing just a little about the first of them, the 1945 Lady on a Train, before sitting down to watch it. I know that I approached it armed with certain expectations shaped in part by the fact that it was part of a box set titled Universal Noir #2 and a title that suggests a mystery on the lines of Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes. Put those two together and I was ready for a darkly sinister thriller peppered with leftfield plot twists, and maybe even a small dash of black humour. I was a good twenty minutes in before it really sunk in that this was not going to be the case. Indeed, based on film’s the first third, I was bemused by the very idea that this could be categorised as film noir at all, as for me it played more like a screwball comedy. So what the hell is such a film doing in a noir collection, you might ask? I certainly did at the time. Stick with it, however, and this categorisation starts to make a little more sense.

It begins wittily enough, with San Francisco debutant Nicki Collins (Deanna Durbin) seemingly confessing to a murder as she travels by train to visit her aunt in New York for Christmas, only for the camera to pull back and reveal that she’s reading from a novel by crime writer Wayne Morgan. When the train stops for signals somewhere short of her destination, however, she witnesses a man being murdered for real by an unknown assailant through the window of a trackside building. Initially left speechless, she quickly recovers and tries to report it to the conductor, but he’s just too busy to take on board what she’s trying to tell him.

Meeting her at the station and charged with keeping a watchful eye on her during her stay is her father’s trusted employee, Haskell (Edward Everett Horton), whose inane babbling to a total stranger while he waits for the train is so a clunky a slice of exposition that it’s almost charming. He meets Nicki as ordered, but she quickly gives him the slip and takes a taxi to the nearest police station to report the crime but is fobbed off by the dumbest desk sergeant on the force, who’s preoccupied with the vital task of decorating a miniature Christmas tree. With the cops uninterested, Nicki decides that the man she needs to recruit to investigate this for her is Wayne Morgan (David Bruce), the author of the crime novel she was reading on the train. After failing to reach him by phone she goes to his apartment, where he’s in the process of aurally composing his latest work and dictating it to his coolly unimpressed secretary, Miss Fletcher (Jacqueline deWit – I liked her immediately) whilst hammily acting out the actions of his literary alter-ego. He initially mistakes Nicki’s report of what she saw as a suggestion for his new book, then inadvertently provides her with a new line of inquiry when he has his fictional detective return to the scene of the crime.

Just as Nicki is cheerfully thanking Wayne and departing, Wayne’s fiancée, Joyce Williams (Patricia Morison), arrives and instantly misinterprets what she sees. But of course she does. Nicki’s attempt to locate the fateful apartment by walking down the railway tracks (don’t do it, kids) fails to turn up anything useful, and on her return, Nicki spots Wayne and Joyce on their way out to the cinema and gives energetic chase, then disrupts the screening by pestering the irritated Wayne further. She’s just on her way out when the face of the man she saw murdered is plastered all over the screen as part of a newsreel report of the supposedly accidental death of shipping magnate Josiah Waring (an uncredited Thurston Hall). The newsreel also includes footage of mansion in which he used to live. Want to guess where our enterprising Nicki heads to next?

There are already a fair few names, faces and plot points to keep track of, but we’re only just getting started here. When Nicki reaches and bumbles her way into the grounds of the Waring mansion, she’s mistaken by his nephew Arnold (Dan Duryea) for the late Josiah’s trophy fiancée, nightclub singer Margo Martin, and invited inside. Here, she is introduced to Josiah’s other nephew, Jonathan (Ralph Bellamy), who lives under the thumb of his sternly disapproving aunt Charlotte (Elizabeth Patterson), and family lawyer Mr. Wiggam (Samuel S. Hinds), who has gathered the family together at this very moment for the reading of Josiah’s will. Each of his nephews is left a token one dollar apiece (something that surprises neither of them one bit), and the rest of his estate and full controlling interest of Waring Industries is left to none other than his beloved fiancée, whom Nicki is now impersonating, of course. It’s thus she who the furious Aunt Charlotte angrily approaches and slaps around the face. Faking distress and excusing herself from the room, Nicki sneaks upstairs to hunt for incrementing evidence, and finds it in the shape of Josiah’s something-spattered slippers (it’s hard to be completely sure whether it’s mud or blood at this point). From the moment of her arrival, however, she’s been regarded with suspicion by Josiah’s cat-stroking private secretary Saunders (George Coulouris), who quickly twigs that Nicki has the evidential footwear in her possession, and after unsuccessfully pressuring her to hand it over, is soon plotting with roughneck handyman Danny (Allen Jenkins) to retrieve it.

It's here that the first hints of the noir element that seeps into the film’s second half first sticks its head above the genre parapet. Not that you’ll necessarily recognise it as such as this stage, as the film hasn’t finished with its light-hearted comedy, and it has one more genre to cycle through yet, one that may well catch those not familiar with Deanna Durbin’s early career on the hop. That said, even as someone aware of Durbin’s musical past, I still was given a jolt when Durbin’s wistful crooning of Silent Night in its entirety down the phone to her father, complete with emotive orchestral accompaniment. Wait, what? Is this a musical now? Not yet it isn’t, but once Nicki heads to the nightclub at which the real Margo Martin (Maria Palmer) works, and twice has to hide her true identity to Josiah’s relatives by performing numbers that she handily knows the words and tunes of, all genre bets are seemingly off.

Based on a story by The Saint author Leslie Charteris and helmed by two time-only director Charles David, Lady on a Train is a distinctly odd concoction, one that throws several genres into a blender and fashions the result into a narrative that flits merrily between light comedy, drama, noir thriller, musical, and whodunnit, often in the very same scene and with sometimes disorientating speed. How charming you find the comedy or even the redoubtable Nicki will be down to personal taste, and fun though some of it is, when it comes to mixing comedy with tension, The Cat and the Canary this most definitely is not. The plot is feverishly busy but peppered with holes, and it’s best to turn a blind eye to some of its logic – the notion that Nicki could impersonate the very different-looking Margo, then sing two numbers in the club at which Margo has been employed for some time without any of the many employees twigging, doesn’t so much strain credibility as toss it off of a cliff. But the film entertains nonetheless, has a hell of a cast, an energetic and surprisingly violent brawl in which both combatants go at it like they really want to hurt each other, and a satisfying finale that makes good on a neat bit of actor-based misdirection. It also features a female protagonist who ultimately proves to be smarter and more resilient than the nominal male ‘hero’, whichever of the three potential candidates he turns out to be. Which means, of course, that if it was released today, it would have snowflake right-wingers everywhere complaining that the filmmakers had gone ‘woke’. Another sound reason for liking it, I’d say.

While we’re on the subject of whether a noir-labelled film is actually film noir, next up we have the 1947 Time Out of Mind, which was based on the best-selling novel of the same name by Rachel Field and directed by Robert Siodmak, who had already established his noir credentials with aplomb with genre classics like The Suspect (1944) and The Killers (1946). Before you start rubbing your hands together in anticipatory glee, however, a little plot would probably be in order.

The story opens on the coast of Maine in July of 1889 at the home of former naval officer Captain Fortune (Leo G. Carroll), an on-the-nose name for a man who clearly made enough dough from his naval career to be able to afford a sizeable house and the staff to run it. One of those living and working there is Mrs. Fernald (Olive Blakeney), who arrived here from England many years earlier with her daughter Kate (Phyllis Calvert), who is now in love with Fortune’s son Christopher (Robert Hutton). As we join them, Kate and Christopher’s sister Rissa (Ella Raines) are eagerly awaiting his return from a long stint at sea on the Captain’s former vessel, the clipper ship Rainbow. When the Rainbow docks, however, the news is not good. An accident that delivered a severe blow to the head has critically injured Chris, who has been unconscious since with a possible fractured skull. It subsequently emerges that the lad has a passion for music and did not want to go to sea at all but was effectively ordered to do so by his stubbornly traditionalist father, who rejects the very idea of his son following a musical career. “The Fortunes were never tinklers on the piano,” he later tells Rissa dismissively.

Kate and Rissa watch over the unconscious Chris day and night and eventually he comes round. A few days later, dressed in his nightgown and his head injury still bandaged, he is drawn downstairs by the sound of the piano tuner at work and begins playing the instrument again. As he is joined by the still concerned Kate and Rissa, he musically expresses his clear hatred of almost all aspects of seafaring, only calming when he reflects on the “strange and fascinating” ports and people that he encountered when the Rainbow finally reached land. Rissa, it turns out, has a surprise for him, as while he was away, she sent one of his compositions to celebrated French composer, Pierre Duval, who replied commenting favourably on Chris’s talent and potential. Chris is dismissive of the immature nature of the musical piece in question and his own current compositional skills. “If only I could go to Paris, study with a man like Duval,” he passionately muses, “maybe I could do something, something worthwhile.” Just seconds after he finishes playing, however, his father appears, tells Chris that he’s glad to see him out of bed, then suggests that he engage in more strenuous exercise in order to strengthen himself up for the Rainbow’s next voyage. Mortified at the prospect, Kate and Rissa secretly borrow money from successfully entrepreneurial former house handyman, Jake Bullard (Eddie Albert), to allow Chris to flee to Paris with Rissa and follow his dream while Kate waits dutifully for him at home.

Although often labelled a film noir, Time Out of Mind does stretch the definition of the term, and to be honest plays more as like romantic melodrama. Indeed, more than one commentator I’ve read has drawn comparisons to the British Gainsborough melodramas of earlier in the decade, one of whose stars was this film’s lead player, Phyllis Calvert. On that score, it ticks a many of expected boxes, particularly once Chris later returns home with a few unwelcome surprises for the devoted and self-sacrificing Kate, who repeatedly puts his welfare and happiness above her own. It’s an often thankless task for someone I’m not convinced deserves it, and even sees her forcing him to go cold turkey after booze comes close to completely destroying him, despite the fact that he fell for the insufferably self-centred Dora Drake (Helena Carter) whilst he was in Paris. It builds to exactly the finale you are primed to expect, but with the unexpected potential for disruption at the hands of Dora’s spiteful bitchiness.

As a melodrama, Time Out of Mind is a solid-enough entertainment, one fluidly directed by Siodmak and atmospherically shot by cinematographer Maury Gertsman. The score, by Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco and Miklós Rózsa, is obviously a key factor here, and what does impress is Robert Hutton’s commitment to selling its in-film performance as real. It’s quite possible that he was an accomplished pianist, of course, but if not, he does a fine job of miming the correct moves for the music that we see him playing. There’s no need for the usual trick hiding his hands as he plays here, which not only makes a refreshing change, it helps to sell the idea that he’s a musician of as-yet unrecognised talent. The performances are sound enough across the board, but quietly stealing the few scenes he is in – at least for me – is former British stage actor John Abbott as music critic Max Lieberman, whose initial tetchiness is interestingly fleshed out when he re-enters the story at a later stage. It’s the cast, Siodmak’s direction, and the emotional ups and downs of the story that ultimately carry it, and while I did enjoy and greatly admire aspects of the film, it’s not one I can see myself going back to that often. I certainly liked it more than its director, though, who in the Summer 1959 issue of Sight & Sound described it as “a preposterous film,” also expressing some relief that, “they played the film for just one day in a tiny Park Avenue cinema then it disappeared forever." Ouch.

If you’ve ever complained about uncomfortable airline seats – and I certainly have – just wait until you see the conditions that the post-WWII tourists in Singapore have to cheerfully endure to reach the island country of the title. For a few crucial second as the film began, I seriously thought I was looking at the interior of a military plane from which the passengers were expected to exit by parachute. Amongst them is American Matt Gordon (Fred MacMurray), a former resident of the country who left following the Japanese invasion in 1942, and whose return five years later is not exactly welcomed by Deputy Commissioner Hewitt (Richard Haydn), who reminds Matt that it is still illegal to “remove pearls at sea” and take them out of a British colony like Singapore. Matt smiles and repeatedly assures him that he was only shipping copra, but it’s clear from the way the two men politely interact that Matt was indeed a pearl smuggler, and that while Hewitt is fully aware of that fact, he has so far been unable to prove it.

So with the authorities mindful of his former activities, why has Matt returned to Singapore after all this time? He claims it’s just to see how the place has changed, but I’m buying that about as readily as the wily Hewitt. He’s certainly welcomed as a familiar face at his hotel by long-standing receptionist Cadum (Frederick Worlock), from whom he requests room 202, the suite he regularly occupied before the war. Unfortunately, this has already been reserved for two of Matt’s fellow travellers, eager tourist Mrs. Bellows (Spring Byington) and her amusingly grumpy husband Gerald (Porter Hall). Cadum is able to offer Matt the room next door, and after a brief moment of uncertainty, that seems to satisfy him. When he looks around the lobby bar, however, his cheery disposition fades, as he is drawn by a sad memory to a particular table on the far side of the room.

It’s here that Matt begins to share his thoughts with us in voiceover for the first time, and in a soft focus dissolve we’re taken back to this very same spot in December of 1942, where Matt is drinking gin slings with a woman named Linda Grahame (Ava Gardner). The two have known each other only a short time but are deeply in love, and with the world at war and Singapore at risk of invasion, Matt has secured Linda a place on the last passenger ship out of the country to transport her to safety. The two hate the thought of being separated, and at the last second Linda runs from the ship and back into Matt’s welcoming arms. Their plan to immediately marry is temporarily dashed by a legally required three-week waiting period, but they are able to persuade the priest to shorten the wait considerably after news arrives that the northern part of the peninsula has already fallen to the Japanese.

This proves to be a fateful decision for the couple. When they return to Matt’s room on Christmas evening, they catch a weasel of a thief named Sascha (George Lloyd) hiding on the balcony. When accosted by Matt, he claims to have come here to tell him that someone named Mr. Mauribus (Thomas Gomez) still expects to see him, but as he attempts to leave, Matt grabs him and relieves him of an item he has tucked into his jacket, which turns out to be Matt’s Christmas present to Linda. This is the first indication to Linda of the criminal life that Matt has been carefully keeping from her, but she quickly brushes it off, even when Matt’s Christmas gift turns out to be a necklace comprised of pearls that someone like Matt couldn’t possibly afford. In a neat associative cut, the necklace placed around Linda’s neck by Matt, then immediately unclasped and removed the following day by Hewitt, who has called the two into his office to question the origin of such a striking string of pearls. Without batting an eyelid, Linda confidently spins a story about buying the necklace in America from a company that imports jewellery from all over the world. Oh yes, she’s a keeper for sure. But then…

OK, here comes that spoiler warning I mentioned in my introduction, as in order to get to the end of this flashback and return to the Matt Gordon of 1947, I’m going to have to reveal a plot point that first-timers might not want to know about in advance, though I will keep schtum about the solution to the mystery that this creates. If you want to bypass this, give the next two paragraphs a miss, or click here to do so automatically.

A short while later, as Matt and Linda are about to be married, news arrives that the military have taken over the hotel to prepare for the imminent Japanese invasion. By now we’re aware that Matt has hidden a large consignment of pearls in his room, and desperate to retrieve them he temporarily leaves Linda and returns to the hotel, only to discover that his room is now occupied by military personnel. By this point the bombs have started falling, and when Matt returns to Linda he discovers that the orphanage in which she was taking shelter has been destroyed. He enters the wreckage in the hope of finding her but is quickly knocked cold by a falling beam and dragged by a navy officer from the building. When a subsequent and more thorough search turns up nothing, Matt is forced to accept that Linda was killed in the attack, and with Singapore now falling to the Japanese and no good reason to remain, he boards his schooner and leaves the island. Now he has returned in the hope that the pearls are still where he secreted them five years earlier, in the process reconnecting with smooth criminal kingpin Mauribus and his slimy minion Sascha, who are well aware why Matt has returned to his former hunting ground. Then, one evening, Matt is socialising with the Bellows when he spots a woman on the dancefloor who is an exact dead ringer for his lost love, Linda. When he approaches her, however, she claims not to know him, and is politely informed by her dance partner that he must have confused his wife for someone else. If this twist has a familiar ring, then it’s because a similar setup was at the core of Alfred Hitchock’s 1958 masterpiece Vertigo, as well as a sprinkling of later variations on the same theme, including Brian De Palma’s 1976 Obsession. The woman with Linda’s face is named Ann (also Ava Gardner), and the man to whom she appears to be happily married is plantation owner Michael Van Leyden (Roland Culver). Whether Ann is or isn’t who she claims to be, and whether Matt will accept it even if she isn’t, dominates the film’s midsection and impacts heavily on the final third.

There can be few devotees of classic cinema who do not twig that Singapore was born from the success of Michael Curtiz’s 1942 Casablanca, and the influences extend beyond the single-word exotic title location, with Mauribus standing in for the earlier film’s Signor Ferrari, Sascha making for a sleazier Ugarte, and Hewitt a very British replacement for Captain Renault. Just as the unexpected reappearance of Isla turns Rick Blane’s life upside down, the appearance of his former fiancée’s doppelganger has a similar impact on Matt, and is also complicated by the fact that she is married to a man that he has not previously met and with whom she is clearly in love. Such comparisons do not exactly flatter the later film, but if you can put them aside – or at least on hold – then Singapore still has a good deal going for it. Fred MacMurray makes for a solid leading man, having already earned his noir actor gold card in Billy Wilder’s genre classic Double Indemnity three years earlier, although he’s almost outshone by a luminescent Ava Gardener, who had only recently hit the big time with her performance in another noir giant, Robert Siodmak’s 1946 The Killers. A solid enough supporting cast does an efficient job, but the characters do sometimes lack the distinctive personalities and screen presence of their Casablanca counterparts. That said, given that this corner of Singapore was created on the studio backlot in California, it’s pleasing to see the Singaporean locals played by oriental actors, including a prominent supporting role for Michigan-born Gloria Fong, aka Maylia, as Linda’s loyal maid, Ming Ling.

For all its borrowings, I really enjoyed Singapore, which unfolds at a lick and whose mid-film narrative twist takes the story in an interesting new direction, one that kept me wondering how things would turn out right up to the final scene. Ah yes, the final scene. Without wishing to drop an accidental spoiler, I do have to address what for me (and for writer Philip Kemp in the accompanying booklet) is the film’s weakest element. I’m not going to reveal what unfolds but will say that just as I was in the process of praising the film for what was clearly doing to be the first truly noir ending of the set, it suddenly does a do-me-a-favour switcheroo that looks suspiciously like a studio-enforced addition. That aside, The Lodger (1944) and Hangover Square (1945) director John Brahm brings Seton I. Miller and Robert Thoeren’s nicely structured screenplay to the screen with some aplomb, really dialling up the noir when Ann is kidnapped and violently beaten by the ghastly Sasha for information she doesn’t have. There’s also a moment that would serve as a lesson in compassion for present-day politicians in my home country, when as Singapore falls and Matt prepares to flee the island on his schooner, he insists on taking as many refugees as he can carry.

| A WOMAN’S VENGEANCE (1948) |

|

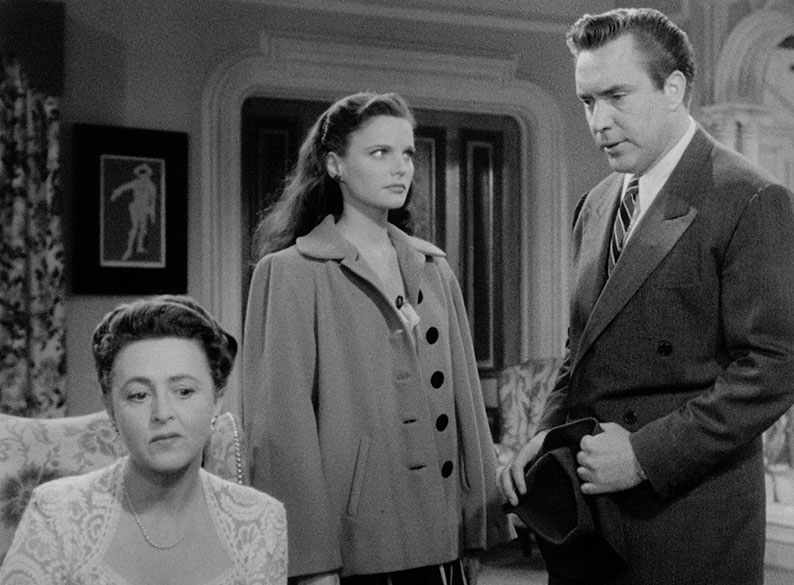

Henry Maurier (Charles Boyer) is not the happiest of married men. His wealthy wife Emily (Rachel Kempson) is an unwell neurotic who dotes on her layabout playboy of a brother Robert (Hugh French), whom Henry has no time for and who only seems to visit Emily in order to flatter her out of more of her money. Emily has become convinced that Henry hates her because of her illness and claims histrionically that he wishes she was dead. “Oh, I certainly shall if you go on much more like this!” Henry responds in frustration, a spur-of-the-moment remark that is overheard by Emily’s nurse Caroline (Mildred Natwick) and that risks coming back to haunt him later.

Henry then departs to deliver birthday gifts to long-standing family friend Janet (Jessica Tandy), who lives with and takes care of her handicapped father, General Spence (Cecil Humphreys), and who shares Henry’s passion for literature and modern art, something Emily has no time for. On his arrival, requests that Janet come to lunch the following day to act as a peacemaker between him and Emily, an invitation that she happily accepts. When she asks what it’s all about and Henry says, “The usual thing,” and the General pipes up with, “What, women?” to which Henry responds, “In this case, it happens to have been something else,” slyly clueing us in to one possible reason for Emily’s unhappiness. The first sign of the times comes when Henry suggests that after 20 years a wife should come to share her husband’s tastes, and Janet responds with, “Yes, of course.” You think so? What about you making an effort to share hers, eh? No, I thought not. At one point during their conversation I began to suspect that these two were more than just good friends, but in no time at all Henry is on his feet and claiming that he has to drive to Windsor to collect Emily’s prescription, insisting as he does so that Janet need not walk him to his car. We soon find out why, as waiting for him there is 18-year-old Doris Mead (Ann Blyth), the woman that he is currently having an affair with. Doris questions why Henry has spent so long with Janet, and remarks that she must by “awfully old.” In a second sign of more chauvinistic times, Henry responds, “From your point of view, she practically has one foot in the grave. And from my point-of-view, she is a handsome young woman of thirty-five. As a matter of fact, she used to be really beautiful ten years ago.” It’s worth noting that Charles Boyer was in his late 40s when he made this film, and we can presume that Henry is a similar age. No double standards here, no sir.

Before lunch the following day, Janet has a talk with Emily, who claims that the only reason she is still alive is that her death would make Henry happy. The maid Caroline, meanwhile, confides her dislike of men to Janet. “Sex. That’s all they think about,” she tells her, a line of dialogue I’m surprised made it past the censors of the day. “I wouldn’t trust any of them,” she continues, then wheels out a prejudicial stereotype by proclaiming indignantly, “And a Frenchman into the bargain.” After lunch, Henry, Emily and Janet relax in the garden, and with Caroline off for the afternoon, it’s Henry who insists on preparing Emily’s medicine. As the others head inside out of the heat, Henry spins a yarn about why he will be out for the evening, instead keeping a date with Doris at a party at which she is being pestered by none other than family sponger Robert, who quickly turns this discovery about Henry to his financial advantage. This proves to be the least of Henry’s problems, as when he arrives home he is met by family doctor James Libbard (Cedric Hardwicke), who informs him that while he was out, Emily has died.

Although initially shocked, just a few weeks later, Henry is off on holiday to Cornwall with Doris where the two are secretly married, and shortly after are planning a trip to Paris. Before departing, however, Henry heads back to the house to collect some papers, and while sorting through them he visited by Janet, whom he welcomes in and to whom he gives a bracelet that once belonged to Emily. It’s then that a thunderstorm hits, and while the camera stays inside the house with Henry and Janet, the spectacular and frankly expressionist ferocity of the storm raging just outside the huge bay window against which they are framed is something to behold. Janet admits to adoring such weather, which it has a transformative effect on her, and in a passionate, thunder-assisted speech to Henry, she comes clean about her long-held love for him, a love she proclaims that they are both now free to embrace. It’s thus no surprise that she’s a little dumbfounded when Henry reveals that he has married a woman half her age. After quickly processing the shock, she laughs off her proclamation of love as a joke and assures Henry that they are still friends. But when Caroline later expresses her suspicion that Emily may have been poisoned by Henry, Janet’s initial protestations give way to a look that suggests she wouldn’t mind seeing the finger of suspicion was pointed at the man who in her mind so cruelly rejected her for someone younger and superficially prettier.

If it looks as if I’ve given a lot away above, well, I have and I haven’t, as this is all effectively setup for what follows, and there is some visible foreshadowing at an early stage, but foreshadowing of what? I’ll spoil a bit more (hop to the next paragraph to avoid) and reveal that immediately after Caroline’s conversation with Janet, the order is given for Emily’s body to be exhumed, and at the following inquest it’s confirmed that she died of arsenic poisoning. The thing is, by this point it’s hard to say just who might be responsible. Henry’s infidelity and the speed with which he married Doris, coupled with his plan to leave the country, makes him the obvious suspect, but it’s also possible that the deeply unhappy Emily took her own life in the knowledge that Henry would probably be blamed, making good on her earlier remark to Janet and justifying the title. And what of Janet, who initially believed that Emily’s death would allow her to finally be with the man she has loved for so long? At first this seems unlikely, as even after realising that her love for Henry would remain unrequited, she fervently dismisses Caroline’s suggestion that he could have murdered his wife. She also remains on friendly terms with Doris, and stoutly attempts to defend Henry at the subsequent inquest, yet the initial suggestion that she might be quietly enjoying seeing Henry suffer – a woman’s vengeance, once again – may mask the possibility that she is be harbouring an altogether darker secret, something that does not go unnoticed by the astute Dr. Libard.

Written by none other than Aldous Huxley – he of Brave New World and Eyeless in Gaza – from his 1921 novelette, The Gioconda Smile (a far more seductive title that the studio apparently rejected for the film), and directed by Zoltan Korda (he of The Elephant Boy, The Drum and The Four Feathers), A Woman’s Vengeance tells a riveting tale that kept me guessing well into the second half and continuously uncertain about how the story might conclude. It’s perhaps the strong noir influence that sees the film question judgemental attitudes to characters that are too often presented in shallow and even stereotypical terms, a fate reserved only for the oily Robert here. Thus, the fact that Henry is an unrepentant adulterer doesn’t mean he is guilty of murder, and that Janet is the victim of an emotional gut-punch at his unfeeling hands doesn’t make her innocent by default. This refusal to paint characters in conventional colours is most evident in the film’s – and by association our – clear sympathy for Doris, who is quickly revealed not to be the young gold-digger of cinematic cliché, but a genuine innocent whose love for Henry proves to be very real, so much so that it nearly leads to a second tragedy.

The performances are all absolutely first-class. In the early scenes, Charles Boyer does a bang-up job of painting Henry as a man you can find simultaneously engaging and just a tad reprehensible, which adds nicely to the later uncertainty about his guilt or innocence. In some ways, this is a very noir trait, an antihero whom we quietly root for even as he remains almost indifferent to – and emotionally unaffected by – the hurt feelings of others, an attitude that risks contributing to his possible downfall. Ann Blyth ensures that Doris is always more than just “the other woman,” and in the film’s second half almost becomes its female lead, which is acknowledged by her cast list's second billing. But stealing the film in a genuinely dynamite performance is Jessica Tandy as the emotionally wounded Janet, who says so much with a single look or a slight change of expression that you’ll find yourself second-guessing her at every turn after her too-casual rejection by Henry. She’s just terrific here, never more so in an extraordinary scene in which she visits the incarcerated Henry and delivers the most electrifying monologue from Huxley’s consistently excellent script. It’s a sequence made all the more powerful by the subtle expressionism of Bernard Herzbrun and Eugène Lourié’s set design, and master cinematographer Russell Metty’s telling use of light and shadow, a key element of many of the film’s most pivotal scenes – just watch how the shadows fall and shift on Caroline’s face as she moves back and forth when admitting her suspicions about Henry to Janet.

When presented with box sets such as this, I always watch and write about the films in chronological order, and with two films still to go, for me A Woman’s Vengeance is the best yet, a riveting, tightly written and directed and superbly acted noir-soaked drama that had me hooked in its opening minutes, and that dropped enough hints in its first half to leave me uncertain whether I was being subtly clued in or cleverly misdirected. The blame for not going with the sobering ending of Huxley’s original story can probably be laid at the feet of the Production Code enforcers, but the point at which the filmmakers chose to end the story still leaves enough room for speculation. I shall say no more.

For progressive young defence attorney, David Douglas (Edmond O'Brien), having a case heard by hard-line Judge Calvin Cooke (Fredric March) can be a frustrating and even infuriating experience. The judge clearly has a reputation for handing down the harshest of sentences, at least if the description of him as ‘Old Man Maximus’ by the two elderly trial ghouls in the brief pre-title sequence are anything to go by. It’s they who lead us – in a complex single camera shot that takes us inside the courthouse and through two large doorways as the main titles unfold – into the specific courthouse in which David’s latest case is being heard by Judge Cooke. David is arguing that the opinion of a key witness can be as valid as evidential facts, but the judge is having none of it. In response, David infers that the judge is deliberately hindering the defence, eliciting a warning that another such remark will result in him being held in contempt. Clearly these two do not like each other. As David continues his cross-examination, the judge puts the finishing touches to a doodle of a gravestone with the words ’20 Years’ stamped imposingly on it. The case concludes with David’s client being found guilty and sentenced to – you’ve guessed it – 20 years in the slammer. As he leaves the court, David tells his girlfriend Ellie (Geraldine Brooks) that he plans to challenge the ruling on the basis of what he regards as the judge’s prejudicial summing-up. When he then asks Ellie what she’s doing that evening, she tells him that she has to be home for her parents’ anniversary. Wow, our David just can’t catch a break today.

If you paid scant attention to the opening credits and read nothing about the plot in advance (guilty as charged), at this point it would seem clear that David is going to be the film’s central character, a crusading lawyer who will continue with the fight to get justice for his too-harshly punished client. It thus then comes as a surprise when, instead of sticking with him as expected, the camera accompanies Judge Calvin Cooke home instead, where he warmly greets his smiling wife Catherine (Florence Eldridge), who is busy making herself up at her dresser. In just a few brief lines of dialogue between them, a picture is painted of a happily married and good-humoured couple (that the two actors were a married couple and an acting partnership in real life probably helped here). Can this really be the same man who was so intransigent in court just a couple of hours earlier? Oh, but there’s more. Just seconds after Calvin asks, “where’s the girl?” who should walk in, dressed in a bathrobe with her hair done up, but David’s girlfriend Ellie. This means, of course, that Calvin and Catherine are her parents, and it’s their wedding anniversary being celebrated tonight. And Ellie is dating a man that her father dislikes intensely. Oh boy.

The inevitability of eventual domestic conflict between Calvin and David is brought forward when Ellie confides to her mother who she is dating, and the two conspire to break the unwelcome news to Calvin by having his colleague, Judge Jim Wilder (Will Wright), locate David and bring him to the house that evening as his guest. If you think you can predict how this is going to pan out, you’d be partially right, but a couple of surprises are still thrown in to the mix. Yes, just shortly after he arrives, David gets into a testy legal disagreement with Calvin that makes the others uncomfortable and threatens to ruin the evening, but against expectations David and Ellie take their leave before it really blows up, and David is otherwise scrupulously polite to everyone, Calvin included.

Before David arrives, however, the film throws an unexpected curve ball that instantly changes the likely course of the narrative. When Calvin is busy answering the door to their long-standing friend, Doctor Walter Morrison (Stanley Ridges), Catherine suddenly has a dizzy spell and falls into a chair, and when she reaches for her Martini, her hand completely misses the glass, then knocks it over in a manner that suggests she has lost control of her right arm. She quickly regains her composure and says nothing about the incident to her husband, but later reveals the symptoms to Walter by claiming that she is asking on behalf of a friend, an old favourite bit of deflection that Walter quickly sees through. He suggests she pay a visit to his office the following day, where he carries out a whole barrage of tests whilst cheerfully chatting to Catherine in a way that infers this is all just routine. There can be few watching who don’t know full well that it is not. She asks him not to mention this visit to her husband, and he sends her on her way with an assurance that he’ll call her tomorrow with the results and his conviction that it’s nothing to worry about. I can’t believe there will be anyone watching who buys that for a second, particularly when Walter walks back into his surgery with a dark look on his face and orders that copies of the x-rays be sent to three eminent medical experts.

Before I move on, I have to seriously question the ethics of what Dr. Morrison does when he gets the inevitably grim results of his tests. Instead of asking Catherine to come back in and explaining the seriousness of her condition to her, he requests that Calvin come to his office and gives him the full rundown instead. He then advises him to tell Catherine nothing of her condition, and instead to just take care of her and act as if absolutely nothing is wrong, the idea being that she’ll continue to enjoy life if she remains unaware that she doesn’t have long to live. He then calls Catherine and tells her that everything is fine. What? He doesn’t seem to take on board that Catherine’s condition will continue to deteriorate, as she gradually loses control of the right side of her body and suffers intolerable levels of pain. For heaven’s sake, man, she’s going to notice this! Sorry, but I have a very personal reason for calling bullshit on Walter’s actions. Well-intentioned they may be, but his ethics are all over the place, and my personal engagement with this story didn’t end there.*

What follows is a midsection that is genuinely heart-breaking, in part because of what unfolds but primarily thanks to Florence Eldridge’s performance as Catherine, her convincingly expressed joy at the second honeymoon that Calvin takes her on giving way to moments of terrified disorientation and crippling pain. It’s here that the film hits the hardest for anyone who has been through something similar with a seriously or even fatally ill loved one, and it makes it easy to form an empathic bond with Calvin as his despair at his wife’s suffering comes close to tearing him apart. But there’s more, an aspect of the story that is explicitly foreshadowed after Walter has given Calvin the bad news and convinced him to tell porky pies to his wife. In order to alleviate the pain, Walter gives Calvin a bottle of a powerful painkiller called Demarine, which as far as I’m aware is a scriptwriter’s invention. He makes sure that Calvin understands that Catherine should take no more than two tablets every 12 hours, as the drug is toxic in higher dosages. Uh-oh… Yet even then, not everything plays out quite as expected.

Long before I reached this point in the story, I found myself wondering about that choice of title and wondering whether it would prove to be the mother of all spoilers. Adding to my concern on this score is that the man David is defending in the opening scene is accused of murder, and Calvin is shown curtly dismissing David’s claim that the defendant’s state of mind in the lead-up to the crime must be taken into account. Sounds almost as if Calvin is being set up to be taught a very difficult lesson.

While I’m not going to get into how things unfold, I will admit that some of the predictions I made at an early stage (not all of which I’ve chosen to share here) did indeed come to pass, but rarely in the manner that I had expected, and the film still delivered its share of small but ultimately significant surprises. It does seem inevitable that David will be brought back into the story in a professional as well as personal capacity, and the film ends on the sort of overly tidy, self-revelatory speech that Hollywood scriptwriters were sometimes a little too fond of. None of which does serious harm to what remains an engrossing and persuasively performed drama that tackles a delicate subject that I’ve tiptoed around here and that was potentially risky territory for an American movie of the day. And while that midsection may compress months of health deterioration and the impact it has on those loved ones into a few fateful days, they still capture the essence of the experience and manage to pack a serious emotional wallop.

As noir-drenched opening sequences go, the one that fronts the 1949 The Lady Gambles is a peach. Dice are rolled onto the concrete floor of a darkened alleyway, and the magic number seven sees the hands of the winner add a pile of gambled notes to the wad that he already has in his hand. As the camera tilts up, the gambler asks his female companion to kiss the dice for luck, which she does, and he scores another winning roll. As he reaches again for the dice, however, a foot is pressed firmly down on his wrist and the dice are closely examined by the bruisers he is gambling against. The forceful manner in which they are hurled to the ground tells us that the men now realise that they’ve been swindled by conman using loaded dice. The gambler runs and most of the men give chase, while one remains to forcibly restrain the struggling woman. One of the other men then turns round and marches steadily back in ominous silhouette. When he reaches the woman, he pauses for a moment and then punches her sharply in the face. The other man then joins him and the two rain a series of violent blows onto the woman’s face and head, only stopping and running off at the sound of an approaching police siren. It’s a genuinely shocking sequence that later serves as a reminder of just how nasty things could turn should anyone be careless enough to put a foot wrong.

We will soon learn that the woman’s name is Joan (Barbara Stanwyck), and a short while later a reporter named David Boothe (Robert Preston) is shown walking briskly through a hospital the front desk to ask about her. I’ll pause here to make an adjustment to that statement, as the desk in question is not at the front entrance but tucked away down several corridors and manned by a police officer named Murphy (Frank Moran), and David states up front that he knows Joan is here due to a report that came into the local precinct. This suggests, without having to spell it out explicitly, that this is a secure section of the hospital for patients who are facing criminal charges. That Murphy instantly recognises David and casually hands him the admittance log also suggests that David makes frequent visits here in a professional capacity.

As David examines the log, the badly bruised and unconscious Joan is wheeled in and assigned a room by the disinterested duty MD, Dr. John Rojac (John Hoyt), who just seems to want to get back to his lunch. David pleads with Rojac to do something for Joan, but the doc’s in no hurry, and when David protests further, Rojac assures him that if he doesn’t leave he’ll have him thrown out. When Murphy gets out of his seat and approaches the two, David admits, almost reluctantly, that Joan is his wife, and that it’s been over a year since he saw her last. The doc softens a little at this and informs him that as soon as she’s patched up they’ll have to turn her over to the police to face a string of charges that will possibly land her a couple of years in the clink. David tries impress on Rojac that she’s sick, not just physically but psychologically too. The doc remains unimpressed, so Davis tries to explain by telling the story of how his once happy woman ended up being beaten senseless in an alleyway for helping to run a gambling scam.

It’s no surprise that the camera then drifts past David’s shoulder, and via a dissolve takes us back a couple of years to Las Vegas, which David describes to a doctor who has curiously never even heard of the city as, “a wide-open, 24-hour-a-day carnival that lives of three things – quick marriages, quick divorces, quick money, won and lost.” Then, after briefly musing on the upside and downside of gambling, he adds portentously, “But it was just about the worst place in the world for Joan to be.” Quite what she’s doing there when the film begins is initially a mystery, but an intriguing one, as she buys a packet of cigarettes, empties it out, squeezes a small camera into the packaging, and tears a hole for the lens to peek through. She then wanders into a casino and starts surreptitiously taking photos of various tables, which looks suspiciously like she’s quietly casing the joint for an upcoming robbery. In a failed attempt to blend in, she makes a novice’s attempt at placing a bet, and is soon approached by a friendly floorwalker and told that there’s a phone call for her, one that she can take in the manager’s office.

The manager in question, Horace Corrigan (Stephen McNally), quickly grabs Joan’s camera, telling her that he doesn’t like people taking candid pictures in his casino because they could potentially be used to blackmail the punters, which is frankly a fair point. When he makes moves to open the camera and expose the film, Joan spins an unconvincing line about being a tourist before admitting that she used to work for a magazine and was hoping to sell them a story based around candid shots of casino gamblers. I have to presume this would have been more novel when this film was made than it would be today. To my genuine astonishment, Corrigan responds with, “Well, why didn’t you say so? I like the idea fine.” What happened to those previously expressed security concerns, eh, Horace? He even gives Joan a stack of valueless house chips with which to gamble to help her blend in more convincingly, news that she laughingly shares later with David when he returns from a day working on a story at the Boulder Dam. Then, while David is taking a shower and against his express wishes, Joan secretly calls her neurotic sister Ruth (Edith Barrett), whose narrative significance will only later become clear.

When David reappears, he is clearly under the impression that Joan will be accompanying him to the dam the following day, but Joan claims she wants to continue with her photographic project. “Why don’t we see how we feel in the morning?” she suggests as the scene dissolves to the following day, where she’s in back in the casino, not taking photos but playing a game of stud poker. When he spots her at the table, Corrigan takes her aside and warns her against playing poker against such experienced players, only to be surprised and impressed that she is winning. Later, when David announces that his story is almost complete and that they’ll be leaving the following day, Joan approaches Corrigan in the hope of getting some more chips for one last photoshoot. Corrigan invites her to join him for a drink on the patio instead, a chat-up line that is also an attempt by someone who’s been in this business a while to prevent the excitement Joan gets from playing the tables from developing into an addiction.

Thanks to the title and the opening scene, we’re all too well aware that Corrigan’s words of discouragement will ultimately fall on deaf ears and will ultimately result in a parting of ways for Joan and David, and it’s to the film’s credit that the story of Joan’s downward spiral still proves so compelling. A well-structured script by Roy Huggins (from a story by Lewis Meltzer and Oscar Saul, with adaptation credited to Halsted Welles) and tight direction from An Act of Murder’s Michael Gordon are key factors here. But what really sells it is a knockout performance by Barbara Stanwyck as the ill-fated Joan, who really sells every aspect of her character as real, from her early lustful love for her husband to the magnetic pull of her developing addiction to gambling, and the pit of despair and desperation it ultimately plunges her into.

Being told up front that a grim downfall is coming casts a pall of inevitability over even the happier scenes, which instead play as painfully missed opportunities for Joan to escape her increasingly ruinous addiction. The most painful of these comes after she has seemingly hit rock bottom and is discovered staring vacantly into space in a seedy bar by the desperate David after a citywide search. In the aftermath of this she seems to have everything going for her, as she and David move to a rented coastal cottage that they hope to buy from the proceeds of the book David is writing and that Joan is typing up for him. Then, on a trip into town one day, she by chance bumps into the Sutherlands (Don Beddoe and Nana Bryant), a lively middle-aged couple with whom she gambled in her Vegas days, and they reveal that the husband has discovered a gambling den behind their hotel and invite Joan to join them for the evening. The thing is, by this stage she clearly realises what a dangerous move this would be and thus turns them down, but Mr Sutherland badgers her relentlessly, and despite politely and repeatedly declining his offer, she ends up reluctantly accompanying them anyway. When they reach the craps table, just being there is obviously having a seriously discomforting effect on Joan, and when asked by Sutherland to roll the dice, she defensively grips the table edge and declines. But Sutherland persists and Joan eventually relents, and the moment she throws a seven she is effectively doomed. Some of Stanwyck’s most subtly excellent acting is on display here, from the clear fear in her face at what effect just coming to this den might ultimately have on her, to her small but telling lip lick after throwing the dice, and the excitement that consumes her on the second roll. That she runs from the establishment when she realises what is happening to her provides a brief gimmer of hope, but by then the hook has sunk it's only a matter of time before she's reeled back in. I’ll be honest and admit that not only have I never been a gambler, I have genuinely never understood its appeal. But I do understand addiction and have dealt with it first-hand, and while the pull may be different, the tell-tale signs here – from the dangers of peer pressure and the rush that winning gives Joan, to her late film willingness to do just about anything to get the money for another hit – allow her gambling to also be read as a metaphor for drink or hard drugs. It’s perhaps this that saw some compare the film unfavourably to Billy Wilder’s brilliant 1945 study of the ruinous effects of alcoholism, The Lost Weekend. But while this metaphor still stands, the decision to focus specifically on gambling addiction at a time when the condition was not even widely recognised as a legitimate problem was crucial to bringing the issue to wider public attention. And as a drama, it delivers. Yes, for some the resolution will be a little too pat, but that shouldn’t take away from what is otherwise a rivetingly told tale about a serious but once little-understood issue that showcases a seriously talented screen actor at her very best. And watch out later on for the good-looking boy who delivers a telegram to Joan later on in the film.

Part 2: Tech Specs, Special Features and Summary >>

|