|

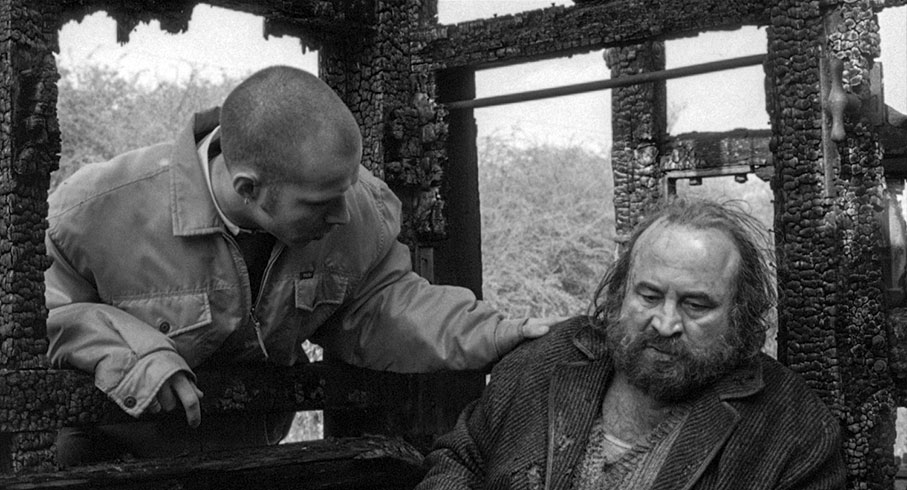

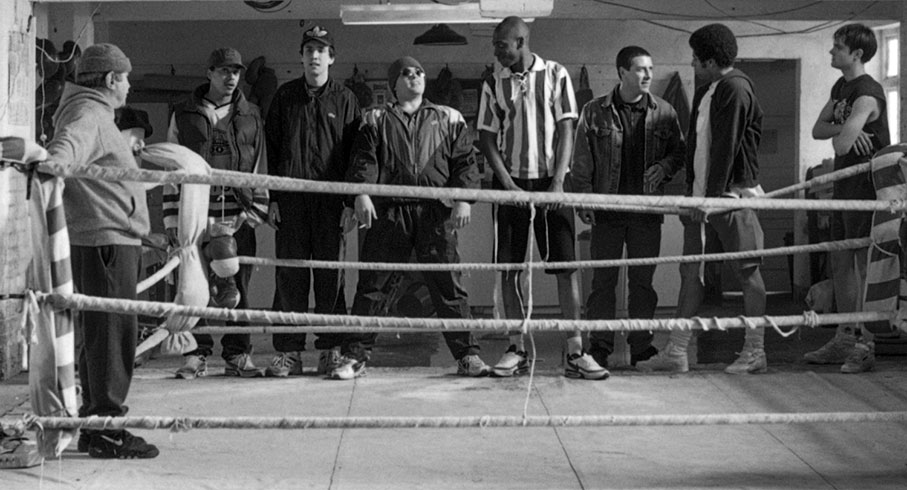

Nottingham, the mid 1990s. There’s nothing much to do for the teenage boys in the area except to run around in gangs and take drugs. Darcy (Bob Hoskins) sets up a boxing club so that the boys can be kept off the streets and be given something they can believe in...

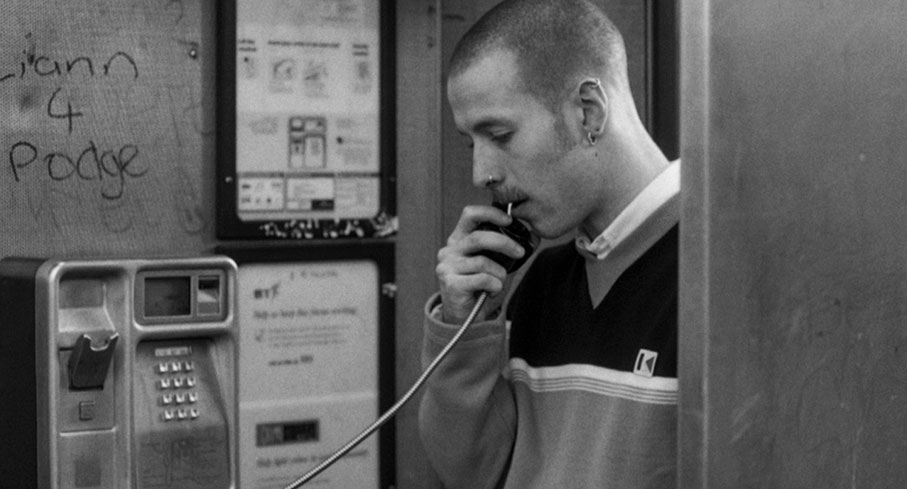

TwentyFourSeven (it’s spelled that way on screen, as one word, and there’s also a counter going up to 24 7 during the opening credits) was Shane Meadows’s second feature film - or first, if you don’t count the 61-minute Smalltime (1996). (Smalltime has been released by the BFI on DVD, paired with the short Where’s the Money, Ronnie? from 1994.) Meadows had taught himself to direct by making short films quickly and cheaply on video, some twenty-five of them in the space of three years. It was Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets which inspired him to become a filmmaker, noting that Scorsese had made a film about the area he had grown up in and lived in, about the people he knew. So why couldn’t he do the same with his local area, namely Nottingham and surrounding parts of the East Midlands? TwentyFourSeven was in part inspired by boxing and football clubs Meadows had attended in his teens. Although Meadows’s talent was already evident, there was a big leap in scale in a year, from Smalltime (shot on video, just over an hour long) to the full-length feature TwentyFourSeven (shot in 35mm, for actual production companies other than himself, with a major star, Bob Hoskins, in the lead). Whether it’s a debut feature or not, depending on which definition of “feature” you use, it’s a fine piece of work: very well made, beautifully shot in black and white by Ashley Rowe, with a strong performance by Hoskins supported by several young actors who would go on to long careers.

Made for BBC Films and (executive producers) Stephen Woolley and Nik Powell’s Scala Films, cowritten by Paul Fraser and Meadows, despite that avowed influence of Scorsese from across the Atlantic, TwentyFourSeven sits in a tradition of British realism. There’s the use of real locations (though the scenes of the excursion to Wales were actually shot in the Peak District) and often non-professional local actors. You can see precursors in the films of Ken Loach and to some extent Mike Leigh and further back the British New Wave of the late 1950s and early 1960s. In a way the use of black and white for a contemporary subject harks back to that tradition. Black and white had become commercially obsolete in mainstream British and American cinema by the end of the 1960s, with occasional exceptions to the colour norm later and to this day. More than two decades before TwentyFourSeven was made, black and white connoted “realism”, but this was no longer the case, and the few monochrome films made since the 1960s mostly used it to suggest period or history. (More about this in “sound and vision” below, but I’ll note that Loach did himself make a latterday black and white feature, Looks and Smiles (1981). Meadows returned to black and white – shot on 16mm this time – with Somers Town in 2008.)

Many of Meadows’s films are about father figures, to boys especially, and those fathers are often very much flawed men. Darcy certainly is no exception, but in an area riddled with drug use and gang rivalries, he sees his boxing club as something the teenage boys around him can believe him, to give them some structure and meaning. He is contrasted with other fathers. We begin the film with Tim (Danny Nussbaum) whose own father (Bruce Jones) is ready with his fists to not just Tim but his mother Pat (Annette Badland) as well. It’s a confrontation between Tim’s dad and Darcy which provides the climax of the film.

TwentyFourSeven premiered at the 1997 Venice Film Festival and went on release in the UK on 3 April 1998. It was critically well received, and picked up a BAFTA nomination for Best British Film (won by Nil by Mouth). However, it didn’t do especially well in cinemas. As Derek Malcolm says in the Meadows/Hoskins interview on this disc, more often than not British films were not widely shown in cinemas in their own country, and this was not been an exception. Meadows has continued to make films, with Dead Man’s Shoes (2004) and This is England (2006, basis of the later TV series) being particular highlights. His last cinema release was the Stone Roses documentary Made of Stone in 2013, though a new feature, Chork, is due for release in 2026. Otherwise, he has made notable work for the small screen, such as The Virtues (2019) and The Gallows Pole (2023).

TwentyFourSeven is released by the BFI on a single Blu-ray disc encoded for Region B only. The film had a 15 certificate in cinemas in 1997 and retains that on disc.

The film was shot in 35mm black and white and is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The transfer is derived from a 2K remastering from a finegrain duplicating positive. By 1997, it was not only unusual for TwentyFourSeven to have been made in black and white, it was even more so for it having been shot on actual black and white film stock. By that point, most new black and white films were shot on colour stock, post-produced and printed in monochrome for cinema release. There were two reasons for this. Firstly, black and white 35mm film (which was almost always Eastman Plus X) was the same as it had been for decades, while colour stocks had been developed to the point that they were far more sensitive and needed less lighting than monochrome. The second reason was that a colour original meant that a colour version of the film could be produced and released if it was deemed more commercial. Nowadays, many black and white films are shot digitally for similar reasons. However, black and white stock is sometimes still used, and TwentyFourSeven was an example of it. It does have a particular look which is different to that of colour 35mm or digital-capture post-produced into black and white, and if you notice that you’ll see it in this transfer. Blacks are solid, and there is a wide range of greys, with natural and filmlike grain. Contrast, which is vital to monochrome, is spot-on. (The IMDB says that some scenes were shot in 16mm, which seem by eye to be the brief flashbacks of Darcy as a boy.)

TwentyFourSeven was released in cinemas with a Dolby soundtrack, and that’s the basis of this disc’s sound mix, rendered as LPCM 2.0, playing in surround, mostly used for the music. English subtitles for the hard of hearing (and non-native speakers who might find strong regional accents not always easy to make out) are available on the feature only.

Commentary by Andrew Graves

A newly-recorded commentary for this disc. Andrew Graves is not only a film lecturer and writer, he is also based in Nottingham. This does enable him to clarify some local references which will escape those not from or based in the area, such as myself. Some other references from the time are explained for those listening too young to remember or from outside the UK, such as Bob Hoskins’s then-recent advertising campaign for British Telecom. (Others aren’t picked up on – so for those wondering about the reference to Edwina Currie early on, the then-MP and Parliamentary Under-Secretary for Health in 1988 caused controversy by claiming that the majority of British eggs were infected with salmonella. This led to her resignation.)

For much of the way, this is a very scene-specific commentary, with Graves pretty much describing what’s on screen. However, he does talk about the film’s structure, which is tighter than might at first appear. (Given that the main part of the film is in flashback, returning to the present at the end, some brief scenes near the start of Darcy as a boy constitute flashbacks within a flashback. It’s a tribute to Meadows’s and Paul Fraser’s storytelling that this slips past almost unnoticed.) Graves also talks about how some of the film’s themes play into Meadows’s other work, such as failed or re-established father figures. And he also points out Meadows’s cameo in his own film, in a scene set in A & E with a saucepan on his head, for which he bills himself as “Lord Shane Meadows of Eldon”.

The Guardian Interview: Shane Meadows and Bob Hoskins (79:11)

A video recording from the National Film Theatre (now the BFI Southbank) from 20 November 1997. Following a screening of TwentyFourSeven, Shane Meadows and Bob Hoskins are interviewed by Derek Malcolm. Meadows says that he wrote the script with Hoskins in mind. Hoskins says that he received tapes of some of Meadows’s earlier films before the script. He had a “cold bum” test for scripts he read and this one passed, as he hadn’t noticed his bum going cold as he sat on the toilet reading. Other than him, most of the cast were local. Hoskins, when asked if he would direct again, doesn’t discount the idea but says he learned how to direct by watching other directors at work. (At this point, Hoskins had directed two features, The Raggedy Rawney in 1988 and Rainbow in 1995, and an episode of Tales from the Crypt in 1996. His only later directing credit was in 1999, a segment of the portmanteau film Tube Tales.) He talks about his acting career, including his debut in Up the Front in 1972 – Frankie Howerd didn’t like him. The only time he made a film for the money was Super Mario Bros (1993).) Meadows talks about other British filmmakers, particularly those in the same realist tradition as him (Loach, Leigh and others), and says he appreciates them but his greater influence came from elsewhere. He does talk about the need to make films rooted in their and their makers’ home base, citing Scorsese’s films set in the Italian-American parts of New York he grew up in. Not for the first time in these Guardian interviews, Malcolm brings up the issue that a British film like this will inevitably have a limited audience because most people’s local cinemas won’t be showing it.

Fifty-two minutes in, the three answer questions from the audience, which are hard to make out on this recording. This item is preceded by an advisory from the BFI that it contains discriminatory language about the trans community, specifically a couple of mentions by Meadows of a “ladyboys’ bar”.

Ritchie, The World’s Light-Weight Boxing Champion (0:44)

Made for Pathé Frères in 1914, this newsreel footage comprises two shots of Willie Ritchie from the United States, the reigning lightweight world champion, training for his bout against Freddie (or “Fredy” as the opening intertitle has it) Welsh at Olympia. The match lasted twenty rounds and ended up with Ritchie losing his title to Welsh.

Twelve Hours Punching (1:38)

Ten years later, the Topical Film Company filmed several sets of amateur boxers fighting each other at Alexandra Palace, during one day from 10am to 10pm as the intertitle tells us. So you could have had twelve hours of fights at different weights as the fighters certainly have a go at each other. None of them are wearing headgear, which would be the case for amateur bouts nowadays.

Trailers (4:24)

Two broadly similar trailers (2:08 and 2:15), with a Play All option. The second begins with a caption advising us that it’s a PG trailer advertising a 15 film, which could be a nostalgic trigger for those of us of an age to have been regular cinemagoers in the late 1990s.

Booklet

The BFI’s booklet, available with the first pressing only of this release, runs to twenty-four pages plus covers. It begins, following a plot-spoiler warning, with “Spitting on Your Chips: Class, Shane Meadows and TwentyFourSeven” by Andrew Graves. He begins by comparing Meadows to Loach, saying that the former “never flinches” from story and character without straying into overt political content as the latter often does. Graves makes a distinction between Meadows and other filmmakers who could be called “kitchen sink” and aligns him more with early Bill Forsyth, another writer-director who found his inspiration from his own local area. Meadows, born in 1972, is a product of the 1990s, the last decade of “discernable difference”, and to Graves was the man to depict the working classes from a perspective other than a middle-class one. He describes Meadow’s early output of video-made shorts before TwentyFourSeven, which he finds a more honest representation of the British working class than others. (He makes an exception for the Cornish-set Bait (2019), but dismisses Brassed Off (1996) and The Full Monty (1997) and others as offering “cartoonish, compromised or hackneyed salt-of-the-earth types”. Of course, those two films played widely in British cinemas while TwentyFourSeven – and for that matter Bait – did not.) While characters like Tim’s dad do despicable things – which he compares to Judd in Loach’s Kes – we do get to see how they became that way, “as trapped and downtrodden as anyone else”.

“Down the Pub, Into the Ring: A Nottingham Boxing Story” by Caj Sohal is next. The pub in question was The White Horse, from which Arthur Seaton staggered out of drunk in Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960). If Arthur had gone in a different direction, he could have found himself at the Radford Boys Boxing Club. Sohal’s essay is little to do with the film it accompanies, but a portrait of a real-life version of the club seen in it. Boxing, unlike other sports, is very much associated with working-class areas including this part of Nottingham. As for Sohal, he went in to that club and his hopes lasted as long as it took to be punched in the face. He never went back.

Next up is Tim Coleman with “‘If You’ve Never Had Anything to Believe In, You’ll Always Be Poor: Men and Masculinity in TwentyFourSeven”. Coleman says that men and boys are central to Meadows’s films, with their names often in the titles. There are several father-and-son pairs in the film, some toxic and others less so. Tim especially is caught between two father figures – his actual father and Darcy. However, Darcy is a more positive figure – until he fails Tim at the end of the film – and Coleman sees Meadows’s films, including this one, a better example than the repellent one of the present-day manosphere, when productions like Netflix’s Adolescence making such issues topical again.

The booklet also contains a full cast and crew listing and credits for and notes on the extras, with Ben Stoddart providing short pieces on the two boxing newsreels.

While some references may date it, Shane Meadow’s first full-length feature stands up very well nearly thirty years later. It’s well presented on this BFI Blu-ray.

|