|

Attractive young blonde Molly Stevens is a bit of a flirt. When she plays tennis at the Oakley Park country club, every man there has his eyes locked onto her, which doesn't go down too well with the womenfolk. Later, Molly's lifeless body is discovered in woodland, the victim of strangulation by stocking. Following a request made by the local police to Scotland Yard, no-nonsense Detective Superintendent Mike Halloran is sent to investigate, and soon discovers that a number of the locals have something to hide.

In their own publicity for this very disc, the fine people at Indicator have claimed that the 1957 Town on Trial can be viewed as a blueprint for Mark Frost and David Lynch's glorious Twin Peaks. It's a tantalising claim (and a rather good sell), but while I can see where they're coming from, I'd still suggest that the connection is tenuous. Yes, both involve a big city detective travelling to a rural community to investigate the murder of a young girl and in the process uncovering a few guilty secrets. Actually, having written that down, I'm starting to buy it. But that really is where the similarities end. Twin Peaks was less about story than mood and character and the surrealistic strangeness of the locale and the unfolding events. And the secrets uncovered in Town on Trial are either fairly mundane – an unfaithful husband, a pregnant girlfriend, both of which were probably a lot more shocking back in 1957 – or have little if any real bearing on the plot, except to set up a couple of so-so red herrings. And Twin Peaks took its time with its character scenes and its slow-burn mystery (a luxury made possible in part by its TV series format, of course), whereas the 95-minute-long Town on Trial barrels along at sometimes breakneck speed and gives us scant chance to get to know its characters in any real depth. Mind you, most of those we do get to spend a little time with have little of the intrigue or oddball charm or mystique of their Twin Peaks equivalent, and that includes the Superintendent Halloran, the film's main protagonist. As played by the redoubtable John Mills, Halloran is the sort of cop who gets results through a combination of relentless determination and verbal bullying, a man I couldn't help thinking has blithely made his share of wrongful convictions on his way to the Superintendent's chair. He's not an easy man to warm to, but as he's the one charged with solving the murder we go with him anyway. That said, the intriguing opening sequence (all close-ups and no faces) not only reveals that he eventually gets his man (then again, criminals rarely if ever escaped justice in crime films of this era), but strips the otherwise arresting climax of some of its tension by confirming the outcome in advance of a scene that is played primarily for what-will-happen? tension.

As a murder mystery, Town on Trial is a somewhat raggedy affair. Despite the Agatha Christie scale implications of the title, the list of possible suspects is quickly narrowed down to two after we're sharply encouraged to discount a third when local doctor John Fenner – who's also under suspicion – aggressively browbeats him into trying to confess. Not that this proves much help to Halloran, as despite discovering that people are telling fibs about their past and present lives, he does a somewhat pokey job of uncovering the actual culprit. Mind you, he does get distracted by Dr. Fenner's pretty daughter Elizabeth, a diversion from the main story that adds little to it and disrupts the already uneven flow of the investigation. This is also one of those credibility-stretching romances you often find in movies that kicks off when a woman who was previously at loggerheads with a bullish man suddenly finds herself warming to him when he does something daft or is nice to a child or an animal. Here it's a kid. As a result, in the space of a couple of minutes, Elizabeth goes from a frosty acknowledgement of the detective's earlier rudeness to a smiling suggestion that they go out for a drive.

And yet despite all of this, there's something about Town on Trial that not only held my attention but quickly drew me back for a second viewing. On the initial release, there were complaints about the Americanisation of the film's content and style, and to a degree the charge is justified. The Oakley Park country club would probably be more at home in California than rural England, as would the band of rambunctious teens who pile exuberantly into a car that they immediately crash. And if you're going to film a vehicle arriving at its destination, why not have it hurtle towards the camera and slam to a halt a millisecond before it ploughs into the doubtless terrified camera operator? The hard-boiled Halloran even dresses a little like an American private eye. Some have found this irksome, but I enjoyed this collision of cultural elements almost as much as I did the more satirical approach to the same taken by Stephen Frears' Gumshoe, which was also released on Blu-ray by Indicator this month (and yes, that is an unashamed but unsponsored plug). Yet as pointed out by Barry Forshaw on this very disc, while this American edge to the handling is underscored by an intriguing and very British dose of class conflict. This is particularly evident in the working-class Halloran's undisguised disdain for the privileged set, which could well be at the root of his almost instant hostility to the wealthier locals. He's clearly not one to be pushed around by those who consider themselves his social betters. "I shall make a point of reporting you to your superior," barks outraged local bigwig Charles Dixon, to which Halloran quickly responds, "He's used to that." I'll just bet he is. As it happens, it's Dixon's daughter Helen whose attitude and activities drive the film's second act, as she inherits Molly's mantle as the town sexpot and in turn becomes the focus of attention for the anonymous killer.

Town on Trial is without question a fascinating work. Structurally untidy, it lacks the sort of intrigue, character complexity and consistent focus that would make the investigation of the murder more compelling than it actually is. Yet there's much to hold the attention here regardless. John Guillermin (he of The Blue Max and The Towering Inferno and so much more) directs with sometimes eye-catching flair and makes arrestingly probing use of facial close-ups. Almost offhand comments, meanwhile, open intriguing windows of speculation about characters and their behaviour, and what starts as a murder mystery gradually evolves into a blend of character drama and serial killer thriller. And the church steeple climax, despite being undercut a tad by the opening confirmation that Halloran gets his man, is almost worthy of Hitchcock in its scale and audacity.

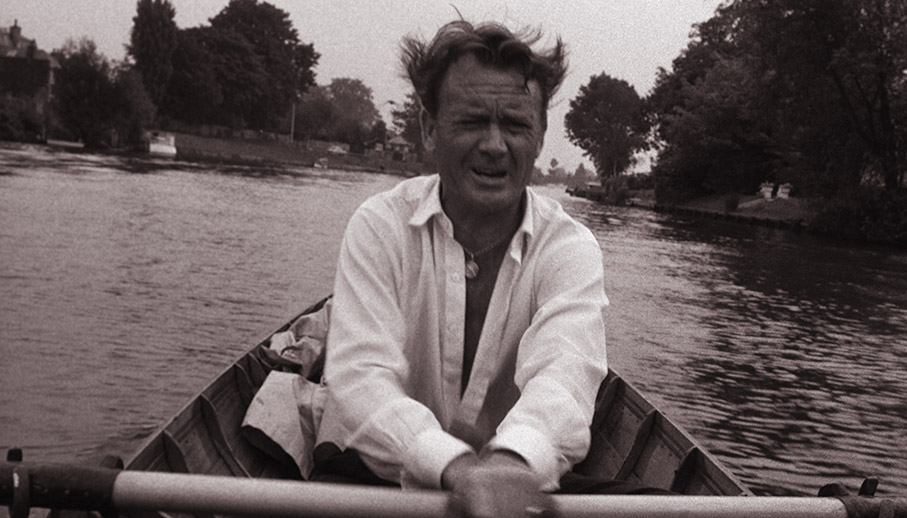

There are, however, two things about the film that oddly niggle me. The first is the look of a couple of the outdoor scenes, and one in particular. Rarely if ever have I watched a film in which rural England looks as glumly uninviting as it does in the sequence in which Halloran and Elizabeth go out on a boating lake. Here the light levels are so gloomy at one point that I was convinced they were about to be hit by a thunderstorm, one that cameraman Basil Emmott did not have film stock fast enough to shoot in without supplementary lighting. And good luck getting that on a boat back in 1957. The second is one I can't discuss without delivering a spectacular spoiler, as it requires me to reveal the ending and debunk the red herrings, so it seems only fair to hide this from view. If you've seen the film or for reasons of your own do not intend to, then you can click here to read this piece. If you've yet to watch the film and still intend to do so, give this a miss and come back to it later, then you can decide if I'm being a little too fanciful in my speculation.

As I intimated above, Town on Trial is not the most visually sparkling film in Indicator's impressive catalogue, but I'm guessing this is down to the condition of the materials used for Sony's restoration. The contrast is punchy, appropriate for Basil Emmott's sometimes noir-like lighting camerawork but strong enough at times to eat the shadow detail for breakfast, and a couple of the exteriors – notably the aforementioned boating lake – are very glum-looking. The coarseness of the grain can vary quite a bit, suggesting that more than one source was used for the restoration, and while previous damage has been digitally cleaned up, the results of this are occasionally still visible. But in all other respects, this is up to Indicator's usual high standards, with sharp picture detail, no motion issues, and a decent tonal range when the contrast is in a more forgiving mood. As you might expect, black levels are consistently solid. The aspect ratio is a slightly unusual 1.75:1.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtrack is clear but with the expected narrow dynamic range and slight treble bias. I heard no obvious traces of any previous damage or wear, however.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are there if you need them.

The John Player Lecture with John Mills

An audio recording of an onstage interview with John Mills, conducted by Margaret Hinxman at London's National Film Theatre (now BFI Southbank) in 1972. As ever with these splendid extras, there is a warning up front about a range of technical issues, but the only real problem is that some of the audience questions can't be clearly heard, but most are repeated for clarification by Hinxman before being answered. Mills is in engagingly chatty form here, and areas covered include his association with Noel Coward, his journey to becoming an actor by way of a job in traveling sales, his work on Ryan's Daughter, Tunes of Glory and Scott of the Antarctic, his admiration for Spencer Tracy, working with daughter Haley on Tiger Bay, and loads more. He does briefly discuss his role in Town on Trial and has a funny story about learning lines for an American TV series. The interview plays as a commentary track, and in a happy if unlikely coincidence runs for the exact same length as the film it accompanies.

Barry Forshaw on ‘Town on Trial' (19:12)

Film historian and journalist Barry Forshaw delivers an enthusiastic appreciation of the film, one well enough argued to prompt me to re-watch it and look at certain aspects in a different light. There's some focus on the character of Superintendent Halloran and the role played by class divisions, and the suggestion that the film prefigures later Italian giallo thrillers is an intriguing one, particularly given that the attacks on the female victims are shot from the point-of-view of an anonymous, black-gloved killer. There's brief coverage of some of the actors and filmmakers, and the idea that one character was quietly coded as gay primarily because he lives with his mother is something that genuinely hadn't occurred to me – it's easy to forget how taboo this subject was back in 1957.

Adventure in the Hopfields (58:52)

It's quite possible that younger (and particularly non-British) film enthusiasts have never heard of the Children's Film Foundation, which was founded in 1951 and was subsidised by a tax on box-office takings known as the Eady Levy. As its name suggests, its aim was to produce films for children, and it built quite a reputation for the quality of its output and the filmmakers and actors who leant their talent to its productions – directors who worked on CFF films included Don Sharp, Gerry O'Hara, Ralph Thomas, Lewis Gilbert and Michael Powell. Yes, that Michael Powell. CFF films rarely ran for more than an hour and became staples at the Saturday morning picture shows that I used to frequent as a kid, but most are nigh-on impossible to track down now. One that was thought lost but has been subsequently rescued (apparently a copy was found in a rubbish bin outside a Chicago TV studio) and restored is regarded by those in the know as one of the CFF's best, and that's the 1954 Adventure in the Hopfields, which was directed by Town on Trial's John Guillermin.

The story is told primarily from the viewpoint of Jenny Quin, the young daughter of a London working-class couple. She begins the story by collecting a freshly repaired china dog that was given to her mother as a wedding present, and in the course of carrying it home repeatedly comes close to having it knocked out of her hands. The bustle she has to negotiate is due to her neighbours all making preparations to travel to Kent in order to make some money picking hops. But despite an invite from her friend Susie to accompany her and her family to the hop fields, Jenny has been told by her parents that she'll have to wait until the following year.

Delighted to see her beloved china dog so immaculately restored, Jenny's mother then places it on the sort of wooden pedestal I'd never put something I valued anywhere near, and then heads out shopping. In an act of clumsiness that sets the tone for her subsequent actions, a distracted Jenny then bumps into the pedestal and sends the china dog crashing to the floor. Distraught at her actions, she leaves a note for her mother and heads off with the aim of accompanying Susie to the hop fields in order to earn enough money to pay for a second repair (good luck with that). But following a series of hold-ups on her journey to the station, Jenny loses sight of Susie's family and ends up travelling with the McBain family instead, unaware that they are heading to a different hop field.

From a more protectionist modern perspective, the idea of a young girl heading off on such a journey on her own might seem like a bit of a stretch, but from the viewpoint of a child of my generation, this would have represented a real and completely believable adventure. It would have particular appeal to anyone raised in an overcrowded and restrictive urban environment, for whom the glorious expanse of the Kent countryside must have seemed as exciting as a summertime trip to the seaside. That Jenny's adventure is propelled and sustained by a series of chance events – a small but crucial number of which are down to clumsiness on her part – may seem a little contrived, but this does set up a handy communication breakdown in which Jenny is under the impression that her parents know just where she is, but they are unable to locate her.

What really and immediately impressed me about Adventures in the Hopfields is that despite overplaying the popular image of working class families saddled with broods of excessively rowdy kids, the characters here actually have an unusually authentic ring. There's an engaging friendliness and camaraderie between the families, and it's clearly by slightly prejudicial design that the only hop-picker with a weed up her rectum is a sniffy spinster with a dislike for kids. We even get a couple of rag-dressed rascals in the shape of the Riley boys, who are there as disruptive antagonists until their actions place Jenny in danger and force a redemptive turn-around, one whose immediate aftermath allows them to retain their reputation as scallywags. And despite this engaging air of casting authenticity, there are some easily recognisable faces here, several of whom would go on to find success in later film and TV roles. Jenny is played by Mandy Miller, who had already made an impression in the title role of Mandy (1952) and would later play the determined Candy in Hammer's The Snorkel, which was also recently released by Indicator (yep, another unsponsored plug). Mrs. McBain and Mrs. Harris are played respectively by Mona Washbourne and Dandy Nichols, and Ned Riley is played by a young Melvyn Hayes. There are also brief uncredited roles for Jane Asher, Edward Judd and Anthony Valentine, but you'll need to be alert to catch them.

Despite its plot contrivances, Adventure in the Hopfields is a hugely enjoyable tale for children and nostalgic adults alike. It's really well made, enthusiastically performed, and moves at the sort of lick that enables Guillermin to cram a feature film's worth of action into one that runs for just shy of an hour without ever it feeling as if he's in a hurry. The most oddly (and almost surrealistically) captivating moment, however, sees the Riley boys pause their relentless troublemaking to rest up inside an old mill they have made their secret place, where they put a record on a wind-up gramophone and lose themselves in the dreamy beauty of the music.

This 1.33:1 print for this transfer was supplied in HD by the BFI and looks terrific.

Shooting Hops (6:38)

Alec Burridge, who was focus puller on Adventure in the Hopfields, recalls working on the film and with director John Guillermin, and has a rather nice story about meeting him again on a subsequent production.

Theatrical Trailer (1:24)

"The secrets and scandals of a whole town shocked into the open!" The whole town?. I think not. A rescue job, by the look of it, hence the soft image and fluffy sound.

Image Gallery

16 slides of promotional stills, posters and press materials, including some of those horribly hand coloured front-of-house cards.

Booklet

I love Indicator's booklets, and this one is up to the expected standard. As ever, it kicks off with full credits for the film, which are followed by a thoughtful appreciation of its virtues by Neil Sinyard, who also provides a brief overview of director John Guillermin's career. We get some entertaining extracts from the film's campaign book ("There is an air of foreboding about the town and its people. Look again at its citizens; at its shopkeepers; at its country-club society; and you will see a race of frightened people"), and Bethan Roberts takes a look at the film career of Barbara Bates, who plays Elizabeth Fenner. Rounding things off are some extracts from a number of contemporary reviews – I was impressed that a footnote has provided to clarify a comment made in one of the reviews that might otherwise fly over the head of a modern audience.

I'm still undecided about Town on Trial. It certainly has its enthusiastic supporters and there's much about it to admire and enjoy, but for me the mix of murder mystery, character study and sly social commentary doesn't gel quite as smoothly as I can't help thinking it could. But it's fun to watch John Mills playing against type and I rather enjoyed seeing rural England get a shot of American police thriller energy and drive. Great disc, as ever, particularly for the inclusion of Adventure in the Hofields, which is essentially a second movie, and thus I have no problem enthusiastically recommending this release.

|