"We don't want false, polished, slick films – we prefer them rough, unpolished,

but alive; we don't want rosy films – we want them the colour of blood." |

The New American Cinema Group, First Statement, 1961 |

"This is a film about people I know, the night people, the jazz

musicians, the drifters and dreamers, the floaters, the chicks,

the smilers, the hangers-on, the phonies, too much sex, not

enough love – and they live in a world of too late blues." |

John Cassavetes, from the trailer for Too Late Blues |

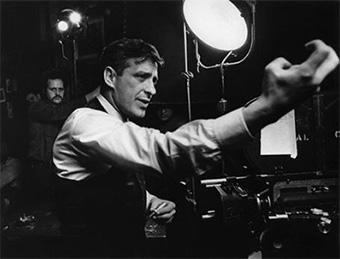

'Accidental genius', 'a constant forge', 'the inventor of forms', 'master of improvisation', 'godfather of independent American cinema' – John Cassavetes is many things to many people and, as those neat labels imply, there is more to his distinctive style than is apparent at first glance. There is also more to his seldom-screened second feature, Too Late Blues (1961), than first meets the eye. The hidden depths beneath its shimmering, monochrome surface have rendered it increasingly interesting in the half century since its release. Those content to recycle the myth of ‘Cassavetes the independent maverick’ have tended to sweep it aside, as an inconvenient truth, along with his two other studio films, A Child is Waiting (1963) and Gloria (1980). Spurned by the public, savaged by the critics, and disparaged by Cassavetes himself, Too Late Blues offers invaluable insights not only into the development of its legendary director but also into the studio system at a time of structural change and jazz culture during the passing of its golden age. Fascinating though the circumstances of its production are, though, it is of more than merely academic interest. It stands on its own two, slightly flat feet as a film full of perfectly realized characters, powerful performances, deftly executed vignettes, and memorable moments of pain and pathos. The long overdue UK release of Too Late Blues, in Eureka!'s magnificent Master of Cinema series, enables us to view this unjustly neglected film afresh and overhaul its tarnished reputation.

Too Late Blues was Cassavetes’ first studio film and the salutary experience of working for Paramount Pictures taught him lessons he never forgot. In a commentary included on that dual format release, David Cairns characterizes the film as a compromised project into which the theme of embattled integrity inevitably seeped. He shrewdly observes that Cassavetes, in his eagerness for artistic autonomy, made a serious mistake by insisting on producing as well as directing the film. Cairns concludes that Cassavetes was, therefore, at war not so much with Paramount as with himself. Given the film's production history, it would be more accurate to say he was at odds with both studio and self. As David Sterrit says in his book Mad to be Saved: The Beats, the '50s, and Film: "Too Late Blues combines a fundamentally conventional approach with the undissimulated vagaries of personality and motivation. Still, the latter appear to grow less from Cassavetes' vision of human complexity and mercuriality (as in his later films) than from the conflict and compromise resulting from his uneasy relationship with Paramount Pictures and its classical-style imperatives." Given that so much of the film's force arises from the tensions between Cassavetes' vaunted integrity and his willingness to compromise, between his yearning for creative independence and a major studio's established production culture, it seems sensible to begin by establishing the positions from which Cassavetes and Paramount approached the project.

As Cassavetes' directorial career began, Hollywood was casting around for a strategy to reverse the downward trend in attendance figures and arrest its post-war decline. The belated implementation of the 1948 'United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc' anti-trust ruling (in which the US Supreme Court decreed that vertical integration amounted to unfair 'price-fixing') had shaved money off Hollywood's bottom line. At the same time, the repressive Hays Code was finally unraveling and the volume production policies of the Big Five major studios (Fox, MGM, Paramount, RKO, Warner Brothers) were gradually being replaced by 'independent' production - a policy forced upon them partly by the challenge of TV and partly by increased competition from imported foreign films (which were not subject to the Code). The achievements of the Italian neo-realists had given the majors pause for thought; the subsequent successes of the French and British New Waves further ruffled the Big Five's feathers; and the explosive impact of Cassavetes' self-funded debut, Shadows (1958/1959), alerted Hollywood to seismic tremors closer to home.

Meanwhile, Cahier du cinéma was rescuing film criticism from literary theory while elevating directors with the politique des auteurs. And the palpable sense that the grass looked greener on the other side of the Atlantic in 1960 is evident in descriptions of the new movement of the moment as cinéma-vérité in the English-speaking world but cinéma direct in the French-speaking world (where stylistic distinctions were more widely recognized). Paramount, which had tended to give directors a freer hand than the other majors and whose defining visual style had traditionally tended more toward European experiment and sophistication, began to see a solution to its many problems in art house cinema. All these circumstances conspired in Cassavetes' favour and persuaded Paramount to offer the fledgling director the security of a long-term contract. Cassavetes was, quite simply, the right man, in the right place, at the right time.

The legend of Cassavetes as pioneering standard-bearer of American independent cinema and the myth of Cassavetes as the master improviser were born the moment Shadows premiered at the Paris Theatre, New York in November 1958. It wasn't well received by its few audiences, but cineaste-critic Jonas Mekas enthusiastically championed it in his Village Voice column and in Film Culture, the magazine he co-founded with his brother, Adolfus (reviewing Mekas' 1963 debut feature Hallulujah the Hills, Jean-Luc Godard said: "Compared to the two leaders of the New York school, Shirley Clarke and John Cassavetes, Mekas looked a little like a poor relation, especially as one never knew whether it was him or his brother."). In Film Culture, Mekas said of Shadows: "The improvisation, spontaneity, and free inspiration that are almost entirely lost in most films from an excess of professionalism are fully used in this film." Shot in short bursts, it featured improvised dialogue, an experimental Charlie Mingus jazz score, energised performances from an enthusiastic cast, and grainy 16mm footage shot in smash-and-grab raids on the streets of Manhattan. It also, incidentally, showed the Beat-Jazz underground as never before and dared to broach the taboo subject of race relations.

Cassavetes himself was dissatisfied with the initial results. He continued to work on the film, removing most of Mingus's score, shooting newly scripted scenes, re-editing the film, and blowing it up to 35mm. In Film Performance and the American Vernacular: The Independent Acts of John Cassavetes, Charles Leary says: "The re-editing, post-dubbing, and additional shooting Cassavetes undertook for the film, producing a more polished version, led Mekas and others to accuse him of trying to capitalize on the underground success of the film to secure Hollywood distribution. Cassavetes withdrew the earlier print and refused to allow it to be screened again. From that point on, the only version of Shadows anyone would ever see was the re-edited version." Until 2004 that is, when Cassavetes specialist Ray Carney unearthed a near-perfect print of the long-lost first version of the film. Discussing Carney's breathtaking discovery in Sight & Sound, critic Tom Charity says: "The 1958 film (operates) impressionistically, in snatches and snapshots of New York bohemia. And there's something very modern about its loose assemblage of scenes linked not by dramatic line but by place, time and mood."

In November 1959, the revised final cut premiered at one of Amos Vogel's Cinema 16 screenings, under the rubric 'The Cinema of Improvisation' Among those few who had seen both versions, opinion was divided. Jonas Mekas preferred the first, more anarchic version (which Cassavetes' widow, Gena Rowlands, always referred to as "a work in progress"), but Amos Vogel favoured the 'final', finessed film. Although Mekas's opinions on the different versions have softened over the decades, he was initially adamant that the first version represented a rupture "with the official staged cinema, with made-up faces, with written scripts, with plot continuities," and that the final version was "a bad commercial film with everything that I was praising completely destroyed."

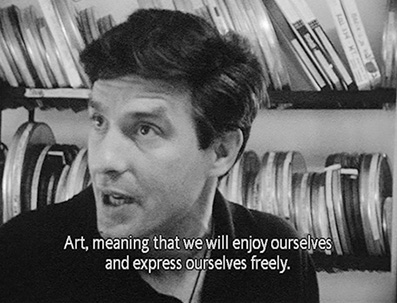

Mekas was speaking, there, in the spirit of the New American Cinema Group which he co-founded, in 1960, with others from the New York avant-garde underground, as a mutual aid society. Partly inspired by the pre-existent Filmmakers Inc collective (founded in 1958 by Shirley Clarke, Richard Leacock, Albert Maysles, Donn Pennebaker, et. al.), the Group's First Statement declared: "The official cinema all over the world is running out of breath. It is morally corrupt, aesthetically obsolete, thematically superficial, temperamentally boring." In its nine-point manifesto, the Group optimistically claimed: "The New American Cinema is abolishing the Budget Myth, proving that good, internationally marketable films can be made on a budget of $25,000 to $200,000. Shadows, Pull My Daisy, and The Little Fugitive prove it. Our realistic budgets give us freedom from stars, studios, and producers. The filmmaker is his own producer, and paradoxically, low budget films give a higher return margin than big budget films." Although the Group were open in their admiration of Cassavetes, he didn't join their ranks. He knew their views, though, and must have been stung, if not surprised by the catcalls that greeted his decision to join a major studio (one can hear Cassavetes now, crying: "Infamy! Infamy! They've all got it in for me!").

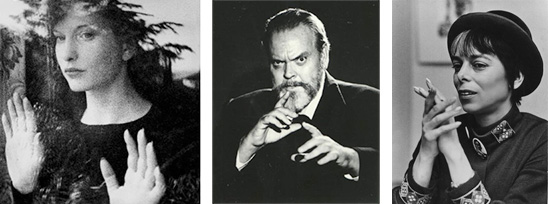

When Cassavetes headed to Hollywood, he had an idea what to expect due his prior experience as an actor. He made Shadows with camera equipment borrowed from Shirley Clarke, but he was helped, too, by the money he'd earned starring, opposite Sidney Poitier, in the feature film Edge of the City (1957). Famously, the public chipped in too: donations trickled in after he'd appealed for public support on the radio talkshow Night People. "If there can be off-Broadway plays," Cassavetes asked on air, "why can't their be off-Broadway movies?" In our era of Kickstart public funding projects, we can but gasp at the prescience and revolutionary daring of that move; gasp and marvel at the changes Cassavetes wrought in film culture. He made more than just films: he made directors. Had he appeared on the scene twenty years earlier, though, he would surely have been marginalised like Myra Deren, the grandmother of American independent cinema, or like Shirley Clarke, the mother of American independent cinema, would be in his own day. Even if he'd made it to Hollywood in an earlier era he would surely have suffered as Orson Welles did. The two men were, after all, cut from similar contrarian cloth.

The circumscribed freedom Cassavetes was granted on Too Late Blues sat somewhere between that enjoyed by Welles when working on Citizen Kane (1941) with supportive RKO Producer George Shaefer and that denied him by Columbia boss Harry Cohen and his henchman Jack Fier during the shooting of Lady from Shanghai (1947). Cohen bugged a portrait of himself that hung in Welles' office at Columbia, which the great director would gleefully salute each evening with the words, "Well, that winds up another day at Mercury. Tune in tomorrow!" Fier's consistent hostility prompted Welles to hang up a huge sign for the attention of cast which read, "We have nothing to fear but Fier himself," and to which Fier retaliated with a sign reading "Alls' well that ends Welles." No such stories emanated from the set of Too Late Blues. Things had loosened up since Bette Davis compared working in the studio system to "the safety of the prison." Although Paramount would hoist some disastrous decisions on Cassavetes, they needed directors like him and he was given a comparatively free hand.

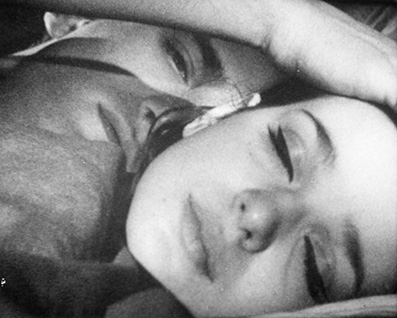

Having accepted Paramount's golden handcuffs, and with accusations that he'd sold out ringing in his ears, Cassavetes set to work developing his story of a struggling jazz pianist, John 'Ghost' Wakefield (Bobby Darin), who sells out by accepting a lucrative but debasing gig twinkling the ivories on the dinner lounge circuit. In the opening scenes of Too Late Blues, Ghost and the quintet he fronts are eking out a subsistence living by playing charity gigs in schools and parks. We watch them as they horse around in their favourite local pool bar, run by Greek immigrant Nick Bobolenos (Nick Dennis). We follow them as they head for an uptown party, where they meet the band's reptilian agent Benny Flowers (Everett Chambers) and Ghost falls for fragile singer Jess Polanski (Stella Stevens). Ghost and Jess peel off to a dive bar then, after slugging back an improvised cocktail, retire to her place, where they circle each other and exchange insecurities. Jess, who has been trammelled by the one-track minds of the men she's encountered, offends Ghost's sensibilities by offering herself to him. He turns her down flat, spurning casual sex in favour of a deeper connection. Their mutual affection subsequently blossoms. Jess joins the band, which begins to prosper. A recording date passes off well, despite an initial confrontation between Ghost and record company boss Milt Frielobe (Val Avery). But, just when a happy ending seems imminent, the film bears its teeth and things turn nasty.

During a celebratory party at their local, a bigoted Irish barfly (Vince Edwards), egged on by ever-destructive Benny, picks a fight with Ghost, who cowers, then lashes out at Jess to spare his blushes. Broken and disconsolate, Jess reverts to type and throws herself at Charlie (Cliff Carnell), Ghost's sax player. After a failed attempt at reconciliation with Jess, Ghost now presses the self-destruct button: at a second recording session, he lashes out again, this time at the quintet, before accepting a Faustian contract to pleasure an ageing Countess (Marilyn Clarke) in exchange for a steady gig. Filled with self-loathing, Ghost clashes with Benny, who replaces him on the bill with the latest in his long line of female acquisitions. At his low point, Ghost seeks out the band, now reduced to dive bars and gold lamé tuxedos, and Jess, now turning tricks and suicidally depressed. His attempts to apologise and repair the damage he's done - to the band, to Jess, and himself – fall on deaf ears and his old friends round on him ("Well, it's a little too late to be crying the blues, now isn't it? I'll tell you what you do, you take your little pink, cotton candy dreams and you get em outta here, and I mean outta here!"). The film, though, leaves us in a minor key, on a note of hope, as the band follow Jess's lead to reprise their too late blues.

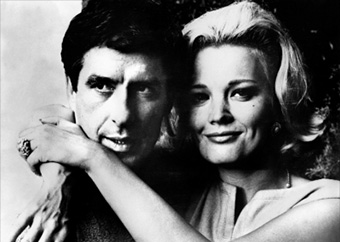

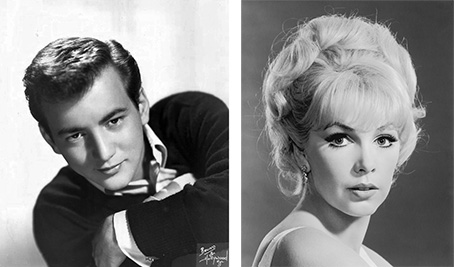

History doesn't record if Paramount pressed Cassavetes for a happy ending, but it would be surprising to learn they didn't. Perhaps he'd dug his heels in or perhaps he'd been given free reign on the script as a quid pro quo for accepting other imposed decisions. Paramount envisaged the film primarily as a showcase for its two leads: Bobby Darin, a pop crooner on the up, and Stella Stevens, a rising starlet already on their books. Darin had already had US Billboard No 1 hits with the disposable ditty 'Splish Splash' (1958) and an easy-listening cover of 'Mack the Knife' (1959). His cover of the Weill-Brecht classic lacks the necessary menace of the German-language versions by Lotte Lenya, Hildegard Knef, Ute Lemper, and, best of all, Ernst Busch's in G.W. Pabst's Die Dreigroschenoper/The Threepenny Opera (1931), but his highly choreographed public performances of the song suggest a fine actor's sense of timing. Darin's talents as an actor are glimpsed during his appearance in Come September (1961), a comedy with Rock Hudson and Sandra Dee (who he married in 1960); they flare up in Too Late Blues, then are buried again in State Fair (1962), a musical with Pat Boone and Anne-Margaret. "I want to do drama, light comedy, the whole range," he said in 1962, "and some day I want an Academy Award." Whether or not Darin saw himself following in Frank Sinatra's footsteps as a light entertainment all-rounder, it's clear his agent was edging him in that direction. There is, then, added piquancy to Darin's performance as a serious jazzman whose agent's definition of success for him is regular infra dig gigs for tone-deaf squares in louche lounges.

We may deduce from Stella Stevens' appearance as 'Appasionata Von Climax' in LiL Abner (1959) that she didn't see herself becoming one of the great character actors of her generation. The way Paramount perceived her was reflected in the roles they assigned her; as a promiscuous alcoholic in Man-Trap (1961), in the Elvis Presley vehicle Girls, Girls, Girls (1962), and in the Jerry Lewis vehicle The Nutty Professor (1963) – at one point in the later, she is frozen in cheesecake pose; slit red dress and stilettos, in bunches and swimsuit, in short skirt and tennis pumps. If central casting saw Stella Stevens as a soft-porn Alberto Vargas cartoon, her appearance, in January 1960, as Playboy magazine's 'Pet of the Month' was hardly designed to make them think twice and she seems to have slipped into the tight dress of stereotype without resistance or regret. Like Monroe and thousands of other actresses, blonde or otherwise, she was delimited by her stunning good looks; her face and figure circumscribed her possibilities and determined the roles she was offered and accepted. Like Monroe, Stevens deserved better and, judging by her performance in Too Late Blues, she was capable of better. She is as stiff as a Kim Novak at times and occasionally miscues her lines, but her very limitations deepen her depiction of dazed, benumbed Jess. The lascivious way she was marketed and marketed herself, also fed perfectly into her portrait of the damaged beauty who jumps from the frying pan into the fire when she ditches Benny for Ghost.

It's easy to imagine the fiery exchanges generated by Paramount's decision to cast Darin and Stevens over Cassavetes' preferred pairing of Montgomery Clift and Gena Rowlands. And yet, the "conflict and compromise" surrounding the film's production accidentally had many beneficial results. Much as we may mourn the missed opportunity of uniting Clift and Rowlands on the big screen (just placing their names together quickened this reviewer's pulse!), the casting of Darin and Stevens proved a triumph. Through a combination of accident and design, that casting decision paid dividends. Both actors gave their all and turned in career-best performances. Darin's superb performance as the epitome of lost innocence and defeated integrity was matched by Stevens' equally convincing one as a hallucinated heroine and casualty of her own allure.

| The Tinsel Beneath The Tinsel |

|

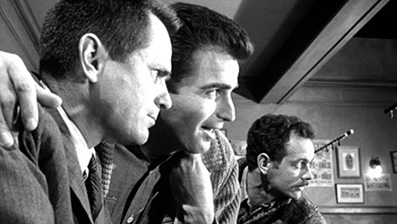

Although Darin and Stevens steal the limelight, Too Late Blues is graced by flawless performances from a committed cast. Although Stevens falters in certain scenes, nobody else puts a foot wrong. Cassavetes, like Robert Guédiguian today, developed a special sense of intimacy by repeatedly working with a revolving ensemble cast of his nearest and dearest. So it is in Too Late Blues. He'd worked with his co-writer, Richard Carr, and Everett Chambers on the jazz-detective TV series Johnny Staccato (1959-1960). He would work with Seymour Cassel, Vince Edwards, and Val Avery again, many times. Everett Chambers almost steals the show as the malevolent Benny, Val Avery insinuates an air of befuddled sensitivity beneath record producer Milt Frielobe's sleazy exterior, Vince Edwards had the muscle and menace to play the lumpen Irish reactionary in Nick's bar to perfection, and Seymour Cassel acts as if he'd been in a jazz band all his life.

Cassavetes deserves applause for his masterful handling of his cast. Shadows had grown out of the improvisation workshops he ran at Variety Arts, and from then on his success as a director would be predicated on performance. It is unsurprising that his defining virtue was his ability to illicit intense response from his actors; he was a consummate actor himself and theatre was his first love. Recall the telling way he framed his public appeal for funds on Night People: "If there can be off-Broadway plays, why can't there be off-Broadway movies?" There speaks a filmmaker with his feet planted firmly in theatre. It's instructive to compare that question with the way François Truffaut frames his discussion of the French New Wave: " . . . intense contact with film is an apprenticeship. People say the New Wave is inexperienced . . . you find in its rank assistants and scriptwriters . . . and people like me who had no experience aside from having watched thousands of films."

Cassavetes pioneered a performative style in which the distinctions between actor and character, film-time and lived-time are stretched to breaking point. That style flowed partly from his use of friends, family, and wife in his films, but also from his background in theatre. Nowhere is Cassavetes' allegiance to theatre – life as theatre, cinema as filmed theatre – more evident than in Opening Night (1977). In that extraordinary play-within-a-play-within-a-film he revealed his methodology and invited us backstage to watch from the wings as acts of pretence and display are transformed into moments of truth. "Peel away the tinsel," as Jean Feuer says in The Hollywood Musical, 'and you find the real tinsel underneath." In Opening Night, Myrtle Gordon (Gena Rowlands) is an ageing actress who struggles free from the stage play that binds her, to improvise an unflinchingly honest performance and demand a like response from her lover, lead man Maurice Aarons (John Cassevetes). In laying themselves bare, the couple(s) embody the ethos of Cassavetes work. As tempers fray, emotions run wild, and tears flow freely, as they often do in his films, we feel we're witnessing life in the raw while occasionally, sometimes simultaneously, becoming aware we're watching a series of acting master classes.

In a paper titled Impromptu Entertainment: Performance Modes in Cassavetes' Films, Pamela Robertson Wojcik says: "Everyday performance can be compared to improvisation, theatricality and entertainment, but everyday performance is meant to be invisible. It's about maintaining social fronts and performing social roles. In Cassavetes, what we see most often are moments of failure in which everyday performance breaks down and characters experience what Erving Goffman refers to as "expressive incoherence", a split between the social front and the personal front." She concludes: "Rather than view Cassavetes as antithetical to entertainment or entertainment as antithetical to authentic experience, we might surmise that the myth of entertainment is the hidden ideology not only of much American feature filmmaking but also of everyday performance."

| The Boy With the Ice-Cream Face |

|

One of the most enlightening and deliciously entertaining scenes in American cinema is the one, in Minnie and Moscowitz (1971), where Minnie Moore (Gena Rowlands) gets spectacularly drunk with her friend Florence (Elsie Ames) and unpacks the ideology of entertainment. Minnie might be speaking for Jess Polanski when she says:

"You know I think the movies are a conspiracy. In mean they set you up Florence. They set you up from the time you're a little kid. They set you up to believe in everything. They set you up to believe in ideals, and strength, and good guys, and romance, and, of course, love. So you believe it, right? You start looking. It doesn't happen. You keep looking . . . and, er, you learn how to be feminine, quotes 'feminine', learn to cook. I never met Clarke Gable. I never met Humphrey Bogart. I never met any of them! They don't exist. No matter how bright you are, you believe it."

Cassavetes was a maverick entertainer who disparaged entertainment. He was a man not of one but many paradoxes. Perhaps nothing did greater damage to clear understanding of Cassavetes than his shorthand reputation as a master of improvisation, which elides his talents as a writer and diminishes appreciation of his magnificent, meticulous scripts. That reputation was partly based on misconceptions shaped by Cassavetes own bum steers. He was a gifted self-publicist with an eye for a punchy one-liner who ingeniously shaped his own legend. We might say there was an air of Sidney Falco, the hungry press agent from Alexander MacKendrick's magisterial masterpiece A Sweet Smell of Success, about Cassavetes. Witness the following Falcoesque sleight of hand. Cassavetes revered Frank Capra above all other directors. Like Capra's Longfellow Deeds and Jefferson Washington, he subscribed to the Puritan idea that humankind has a natural dignity which money and power corrupt and debase. In Too Late Blues, an ode to cynicism but also a Capraesque poem in praise of human potential, a sign placed deliberately in frame, reads "Be Not Greedy To Add Money To Money." In the early 1970s Capra said: "I'd sing the songs of the working-stiffs, of the short-changed Joes, the born poor, the afflicted. I'd gamble with the long-shot players lighting candles in the wind and share the resentment of those pushed-around because of race or birth." Fast forward to the 1980's and Cassavetes says, in Ray Carney's excellent Cassavetes on Cassavetes: "It is my desire to be an underdog, to win on a long shot, to gamble, to take chances."

We might say that Cassavetes was his own greatest performance. In his commentary on the Eureka! disc, David Cairns tells of a friend of his who, in his callow youth, approached Cassavetes after a UCLA screening of Minnie and Moscowitz and had the temerity to tell the director that his film would be better with 20 minutes cut out of it. Cassavetes replied: "I don't want it to be better!" Interviewed by Martin Fine for his unfortunately titled biography Accidental Genius: How John Cassavetes Invented the American Independent Film, Martin Scorsese tells a similar story about his hero. While watching Cassavetes edit a scene from Minnie and Moscowitz (1971), Scorsese had said, "Come on John, get to the point of the scene." Cassavetes rounded on him and replied, "Never!

Cassevetes consistently rewrote, revisited, and reworked. He carefully crafted his signature sense of improvised immediacy and he painstakingly prepared his scripts. In Too Late Blues, as elsewhere in this oevre, he drew superb performances from his cast, but a fine script did much of their work for them. Cassavetes not only deserves huge praise for his writing, he deserves a standing ovation for the way he worked an understanding of his cast and characters into the script. Consider the first, fraught love scene between Ghost and Jess, at the latter's flat, when he rejects her sexual advances and tries to break through her mechanical mindset and socialised self to the real woman within:

Ghost: "Whoever told you that's what you had to do to reach somebody?"

Jess: "Are you kidding? Just where do I stand without my body, huh? Tell me that! I'm the girl with no mind, hadn't you heard? What good is talking to somebody when nobody listens to you, huh? What good is falling for somebody when they don't come back? If I let you go tonight I'd never see you again, and you know it."

Ghost: "And you think the bomb's gonna drop and everything inside'll be out and everything down'll be up, mm?"

Jess: "Uh-uh, I don't think. It's too painful. It's too late for that kinda stuff anyway."

In that one short, tight scene, Cassavetes establishes the two couples' competing sensibilities: Darin/Ghost's boyish, apple-pie-innocence and naïve sincerity, Stevens/Jess's jaded disillusionment and hard-earned scepticism. Throughout the film, there are clear echoes of Clifford Odets and Ernest Lehman's peerless script for Sweet Smell of Success (1957). What does Ghost have? "Intergity – acute, like indigestion." There are echoes in the dialogue, but also in the wider atmosphere of street-wise cynicism to which it contributes. "Match me Sidney," says J.J. Hunsecker (Burt Lancaster) in that magisterial masterwork. "Not just this minute," replies Sidney Falco (Tony Curtis). Cassavetes didn't quite match Odets in Too Late Blues, but there can be no greater compliment than to say he ran him close, both here and elsewhere. Both Cassavetes and Odets calls to mind the late Stanley Kauffmann's argument that hip crosstalk and sharp remarks were to American movies what blank verse was to Elizabethan theatre: a linguistic convention that served to compress everyday language and and change into something else, granting the writer the ability to touch on matters ordinary speech patterns cannot reach without sounding square and awkward. Unfortunately, although Cassavetes is attuned to the intonations and modulations of jazz slang, David Raskin's score for Too Late Blues is out of step with the jazz groove and fails to master the blues idiom.

| Mistakes, Mistakes, Mistakes |

|

If many of the film's imperfections flow from the mistake Cassavetes made by naïvely insisting on director and producer positions (as his beloved Capra and Welles had), Paramount committed two cardinal sins that all but destroyed Too Late Blues: insisting that Cassavetes shoot in the studio and entrusting the soundtrack to David Raskin. Hell, we all make mistakes. In her Short History of Cahier du cinéma, for example, Emilie Bickerton foreshortens Cassavetes' career by describing Faces (1968) as his "second feature." Hers is but a particularly glaring sin of omission: even Cassavetes' admirers have tended to expunge his studio films from the record. I'll get Paramount's first mistake out of the way first because it drew my attention to a howler of my own. It's funny how one's mind plays tricks on one. Before watching Too Late Blues again over the last week, I hadn't seen the film since my student days, when I'd discussed it in a dissertation on Shirley Clarke. I drew on that fading knowledge, earlier this year, in my review of the Cohen Brothers' Inside Llewyn Davis, another film about a struggling musician and embattled integrity in the counter-culture. Embarrassingly, having elided Shadows and Too Late Blues in the mulch of my memory, I made the error (now amended) of claiming the latter was shot in New York. Far from it, Cassavetes, of course, actually shot it at Paramount Pictures in Los Angeles. My mistake, however, pails into insignificance when placed next to the blunder made by Paramount when they transferred Cassavetes from his native New York to the lunatic asylum that is Hollywood and strapped him, kicking and screaming one assumes, in a studio-set-straightjacket.

The cinéma vérité footage Cassavetes shot in New York was so integral to what made Shadows special that it was inevitable that a film shot almost exclusively in a studio would pale in comparison. Cassavetes acknowledged the influence of the neo-realists on his work and singled out Visconti's La Terra Trema (1948), De Sica's Umberto D (1952), and Fellini's I Vitelloni (1953) as "particularly inspirational to me when I made Shadows." He said: "The neo-realist filmmakers weren't afraid of reality; they looked it straight in the face. I've always admired their courage and their willingness to show us how we really are. It's the same with Godard, early Bergman, Kurosawa, and the second greatest director next to Capra, Carl Dreyer." The debt Cassevetes owed Dreyer is evident in the extreme close-ups that punctuate his films, the debt he owed Visconti in his evocations of place, and that to Godard in his spontaneity and improvisational techniques.

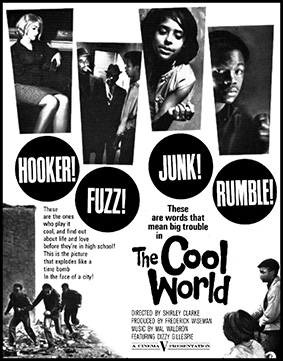

The sense of place sacrificed by his shift from the streets, Shadows, to the studio, Too Late Blues, does untold damage to the latter's integrity. Cassavetes must have realized he'd taken a step backwards when he observed Shirley Clarke's successful step forward from the studio, The Connection (1961), to the streets, The Cool World (1963). The scene in which Ghost finds Jess being pawed by two lecherous johns in a pick-up cocktail bar epitomizes the film's diminution by its confinement to the studio. Emasculated and enraged, Ghost rediscovers the courage he'd lost in the brawl at Nick the Greek's earlier in the film and slaps both men around. He then tosses the last man standing through the saloon bar doors, out into what is manifestly a darkened corner of the studio lot. The sound the man's feet make as he beats a retreat is of leather colliding not with concrete but wood. It is as if we're in a theatre and the stage flats have toppled over.

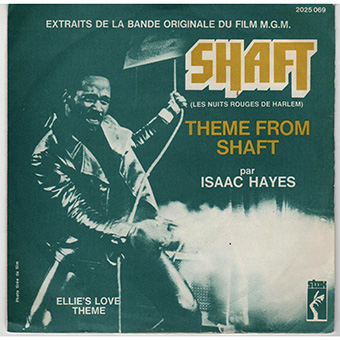

If Paramount goofed by confining Cassavetes to barracks, they screwed up spectacularly by entrusting the soundtrack to David Raskin. Hugely talented, vastly experience, Raskin composed all the music himself, and made a decent fist of destroying the film. His lush, string-laden orchestration is way too refined and understated for Too Late Blues. Aside from the slinky opening number, 'Seal Part One', it's a world away from the sparse poetry, contained passion, and flinty integrity of the blues. Raskin's well intentioned but insipid take on an African-American form sucks dry the lifeblood of jazz: improvisation spontaneity, and soul. The blues from which jazz flowed was too gritty for Raskin and the urban edge of New York's Bebop revolutionaries too unfettered and unpolished. At root, it was all too black for him. Raskin would later revolt against a soundtrack that was clearly too funky for him. He served as chairman of the music nominations committee for the Academy Awards for several years. He held that post in 1971 when Isaac Hayes' 'Theme From Shaft' won the Oscar for 'Best Song', and resigned in protest the same night.

Raskin is best known for his work on Otto Preminger's Laura (1944). Compare that swooning, saccharine score, if you will, with Duke Ellington's swinging, salty composition for Preminger's Anatomy of a Murder (1959). Or, better still, compare the mood-muzak theme tune for Too Late Blues ('A Song After Sundown'), with, say, the Chico Hamilton Quintet's bluesy, gutsy theme tune for A Sweet Smell of Success ('The Street'). Those titles tell their own story. 'A Song After Sundown' would work wonderfully well as a melodic siren song in a different kind of film, but it flops as a composition capable of convincing us of Ghost's musical integrity; even though it hideously delineates the gulf separating hard-edged jazz experimentation and syrupy commercial pap, it signally fails to announce which side of the divide Ghost stands. The film demanded a jazz altogether more dangerous and downhome, raw and rough.

If Raskin's elegant arrangements sell the film short so, too, did his recruitment policy. He selected his musicians for Too Late Blues from experienced studio players but, as with his score, his decisions reflect own predilections rather than the demands of the script. They are solid jazz troopers all (Milt Berhart - trombone, Benny Carter - sax, Shelley Mann - Drums, Red Mitchell - bass, Uan Rasey - trumpet, and Jimmy Rowles - piano). They do their best with the material they were offered. They play tight and in rapport. They know their licks. Unfortunately, by this stage they'd all moved too far toward respectability and too far from jazz's roots and lifeblood: African-American improvisation, spontaneity and soul. Jonas Mekas again, from Ute Aurand and Ulrike Pfeiffer's film OH! die vier Jahreszeiten?/OH! The Four Seasons (1988): "Improvisation is the highest form of concentration, of awareness, of intuitive knowledge, when the imagination begins to dismiss the pre-arranged, the contrived mental structures, and goes directly to the depths of the matter." The music and the musicians should lift the film to greater heights, but the soundtrack is too tidy, safe, West Coast, and white.

Too Late Blues opens with a wonderful sequence in which a group of black school kids click their fingers and swing their feet to the rhythms of a mid-tempo jazz blues played by an all-white quintet. As the band's set ends, an intensely thoughtful black boy jumps up, seizes the sax player's instrument, and runs away with it. Amid general pandemonium, Charlie, the musician (Cliff Carnell) gives chase to reclaim his horn. When he catches the kid ("Can I have my sax back, please!"), the children's joyous din is silenced by their sense of the possibilities of violence. Read in the context of its time, this scene sent out clear signals. As Cassevetes worked Too Late Blues, the Civil Rights Movement was gearing up for mass direct action and the Mississippi Freedom Riders were facing down angry white mobs in the Deep South. This was a time when Billy Holiday's 'Strange Fruit'** ("Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze/Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees") felt less like a reminder of times past, more like a protest about the recrudescence of racist violence. Other than Billy Holiday, only Nina Simone had the guts to perform 'Strange Fruit' regularly. In this context, that scene transmits strong signals. Cassavetes was an apolitical, beat generation libertarian, an anti-Hollywood-mock-Liberal who shared Kerouac's good-ol'-boy patriotism but baulked at his casual racism. He rarely spoke of politics but, when he did, he did so in platitudes. Here, he passes pointed comment.

If my reading of the opening sequence second-guesses Cassavetes' intentions, it is plain that, even if he wasn't deliberately taking sides with his oppressed black compatriots, he was taking sides in the divisive debates that torn jazz apart as its golden age ended in 1960. In an essay for the booklet included in the Masters of Cinema package, David Sterritt interprets the scene as commentary on white society's tendency to sell black music back to African-Americans. He says: "This effervescent scene encapsulates and reverses the enduring scandal of modern jazz – the way music created and cultivated by blacks has been pilfered and appropriated by whites." As Sterritt also argues, in Mad to be Saved, Cassavetes is clearly conscious of the irony embedded in the scene.

While cinema was locked in close combat with TV, jazz was being muscled aside by rock & roll. Like the Pied Piper of Hamelin, rock & rock lured jazz's young audiences away, never to return. Jazz was moving ever further from its roots in the blues while rock & roll began to build on that shared musical legacy and took the Chicago Blues of Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf, and Sonny Boy Williamson forward. And those who paid the piper called the tune: rock & roll tilted the axis of popular music toward the white mainstream and dragged jazz there in its wake. In the fractious turf wars that decimated jazz, mainstream modernists donned three-button suits, courted white audiences, and cultivated intellectual respectability. The black stalwarts of 'free jazz', meanwhile, fought a last stand around improvisation, veered toward atonality, and severed jazz's link with the beat around which it was structured. As the gulf between jazz and its public widened, the isolated avant-garde fought ever more fiercely for its integrity, which further alienated audiences, and so on, until jazz was all but dead. Introducing his book, The Jazz Scene, jazz aficionado Eric Hobsbawn says: "But jazz has always lived not by the hipness of the public but by what Cornell West calls the 'network of apprenticeship', the 'transmission of skills and sensibilities to new practitioners'. By 1960, with jazz clubs closing or becoming bastardized by the demands of white audiences, this network was fraying and some of them had snapped." Cornell West, incidentally, profoundly places Too Late Blues in its context in an incandescent, indelible improvised rap in Astra Taylor's Examined Life (2008).*** The parallels between West's observation and Truffaut's above-mentioned comment on the French New Wave's apprenticeship need no gloss.

Too Late Blues could have recorded jazz's death rattle had Raskin's score not interfered, but it is, nevertheless, rendered vital by that subtext. It stands toe to toe with Roger Tilton's Jazz Dance (1954), Karel Reisz and Tony Richardson's Momma Don't Allow (1955), Edward Bland's The Cry of Jazz (1959), Aram Avakian and Bert Stern's Jazz on a Summer's Day (1960), and Martin Ritt's Paris Blues (1961) in its description of the autumn days of jazz's ascendency. And it's a darker, better film for its depiction of the moment the jazz scene tore itself apart in insult and recrimination, schisms and mutual suspicion. In his book The Films of John Cassavetes, Ray Carney says: "There are profound similarities between Cassavetes' sense of art and that of a jazz composition . . . As in a jazz improvisation, there is no foreseeing where each beat will lead. As in a jazz performance, impulse is not suppressed in order to maintain a straight line of development." Too Late Blues suffers for its comparative lack of improvisation and Cassavetes' maintenance of a straight line of narrative development. As producer-screenwiter James Schamus says in Peter Biskind's Down and Dirty Pictures: "The original sin of the American independent cinema, when it shifted away from the avant-garde, was the introduction of narrative." Too Late Blues also suffers from a soundtrack inadequate to its needs and from being denied the freedom to roam the streets.

Cassavetes learned from his mistakes, and from Paramount's. He would make similar mistakes while working for United Artists on A Child is Waiting. Not Cassavates, Burt Lancaster, Judy Garland, and Gena Rowlands combined could rescue that brave film from Stanley Kramer's sentimentality, but, again, Cassavetes almost pulled it off. He knew these films had a potential that was curtailed by the studios, so he took from the studios all they had to teach him and he heeded Hollywood's shrewdest advice: "Don't come back!" He found his way, became his own man, and then gave us life straight, no-chaser in some of the finest films ever made (Faces, Minnie & Moscowitz, A Woman Under the Influence, The Killing Of a Chinese Bookie, Opening Nights, and Love Streams). In the final chapter of Histoire(s) du cinéma (Chapter 4b, Les signes parmi nous/The Signs Among Us), Godard pays homage to Cassavetes by citing a scene from Faces. As Maria Forst (Lynn Carlin) prepares to attempt suicide after the collapse of her marriage, the accompanying text predicts the death of cinema while reminding us of its immortality: "The only thing that survives from one epoch is the art created from it. No activity can become an art until its proper epoch has ended, then this art itself disappears." Too Late Blues survived the passing of the golden age of jazz and it survived its legendary director, whose greatness it foretells. As fascinating now for its flaws as its achievements, it is to be hoped its stock will rise as time goes by.

Opened out slightly to 1.78:1 from the original 1.85:1 (and thus filling the widescreen television frame), this is a gorgeous transfer of a first-class restoration. The contrast is punchy but not over-aggressive and the tonal range of the monochrome image feels absolutely right for the subject and style. Film grain is visible enough to suggest a high speed stock was used for shooting, but the sharpness and eye-catching level of detail leave the viewer in no doubt that they are watching a film shot on 35mm. Close-ups of faces and background detil in wider shots are especially impressive. The image is rock solid in frame and there's hardly a dust spot to be seen. Excellent.

The Linear PCM mono 2.0 soundtrack is of far beter quality than you might expect for a film made in 1961. Dialogue is clear enough to make you wonder if those responsible for the restoration didn't source the original tapes instead of the optical or magnetic track that accompanied the release prints. Sound effects are also surprisingly crisp (the sound of drinks being poured is clear enough to use on a modern beer commercial) and the music is very nicely reproduced.

The extra features included in the package are:

-

An astute film commentary by academic David Cairns.

-

A booklet containing a specially commissioned essay, 'New Tunes', by David Sterrit, a 1961 profile of Cassavetes by Colin Young and Gideon Buchman, an extract from David Raskin's 2012 autobiography The Bad and the Beautiful: My Life in a Golden Age of Film Music, and an interview with Stella Stevens by Dean Brierly.

Both have been discussed in the main review.

The shimmering monochrome surfaces of John Cassavetes' Too Late Blues reflect the heightened passions and intensified dreams of night. In this imperfect but unjustly neglected film, the long shot loves of riven souls and the fragile freedoms of jazz collide with ice-cold malice and the glaring constraints of corporate day. Pitch-perfect performances, a scintillating script, and Cassavetes’ natural talents ensured that Too Late Blues survived a soundtrack inadequate to its needs, confinement to the studio, and Paramount’s indifference. A fascinating snapshot of an era and an intimation of its director’s coming greatness, it shines more brightly with each passing year. Highly recommended.

*Tom Charity on the Ray Carney's re-discovery of Shadows: http://old.bfi.org.uk/sightandsound/feature/75

**Billy Holiday sings the great protest song 'Strange Fruit': https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h4ZyuULy9zs&index=1&list=RDh4ZyuULy9zs

***Cornell West raps on Astra Taylor's documentary Examined Life: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ns7zLpPShHg

|