|

The Midlands, sometime in the 1960s. Barry (Dave Hill) and Paul (Jim Lea) are guitarist and bassist backing singer Jack Daniels (Alan Lake) in a band managed by Ron Harding (Johnny Shannon), mainly playing weddings. Shortly afterwards, they recruit drummer Charlie (Don Powell). Stoker (Noddy Holder) is the lead vocalist of rival band Roy Priest and The Undertakers. Shortly afterwards, The Undertakers have broken up and Stoker is offered Jack’s place in the band, now called Flame. An argument with Harding results in him dropping from his agency, something which will have consequences later. Talent scout Tony Devlin (Kenneth Colley) recommends them to London agent Robert Seymour (Tom Conti). They sign with him and soon their first record is a hit...

In 1973 Slade could claim to be the biggest band in Britain, certainly regarding hit singles. The combination of pop-flavoured guitar rock with plenty of hooks and deliberately misspelled song titles, was catnip for the British singles-buying public. While they weren’t really glam, some of lead guitarist Dave Hill’s outlandish costumes aside, they rode the glam-rock wave along with such bands as Marc Bolan’s T.Rex and Sweet. In Noddy Holder (lead vocals, rhythm guitar) they had one of the great rock voices of the time, and he and Jim Lea (bass, piano – also violin, featured notably on their first number one “Coz I Luv You” but not played by him in the present film) wrote the songs. Flamboyant Dave Hill did a lot to put them across on stage and the lineup was completed by drummer Don Powell. Slade had had nine top ten hits in a row, with six going to number one. Entering the singles charts at the top was a rare feat then, but in 1973 Slade achieved it three times, with “Cum on Feel the Noize”, “Skweeze Me Pleeze Me” and “Merry Xmas Everybody”, the last-named now a seasonal perennial. The next step, thought manager Chas Chandler, who in the previous decade had been the bassist for The Animals and had discovered and managed Jimi Hendrix, was a movie. The Beatles had had A Hard Day’s Night and in its wake there had been the Dave Clark Five with Catch Us If You Can (John Boorman’s feature directing debut) and others. So, what price a Slade film? The original idea was a science fiction spoof, The Quiteamess Experiment, with Noddy Holder playing the good professor and Dave Hill being offed by a monster in the first scene. Hill wasn’t having that, and so the emphasis changed. Their film would be something more serious, a gritty, indeed downbeat, look at what it really was like to be a rock band, more the struggle to make it than the life at the top. (Slade had been doing the rounds for five years before they started having hits.) The result was Flame.

(There has been much debate on what this film is actually called, but onscreen Slade in is on a different title card and in a different colour to Flame. For reasons of conciseness, I’ll use the shorter title from now on.)

Flame is a period piece, set in the mid-to-later 1960s, though indicators of the time are conveyed with a light touch. So we have a one-armed bandit being fed with pre-decimal currency, the black and white television in the Seymours’ house (colour sets weren’t yet in fifty percent of British households in 1974 when the film was made: that would happen two years later), the offshore pirate radio station (which was more 1960s than 1970s).

The film was made by Goodtimes Enterprises, David Puttnam and Sanford Lieberson’s company, which had form for making music-based features often featuring real singers and musicians. Performance (1970) isn’t really a rock film, even though it did star Mick Jagger and has a prototype promo video in “Memo from Turner”. It shares actors Johnny Shannon and Kenneth Colley with Flame. While The Pied Piper (1972), starring Donovan and also co-written by Andrew Birkin, had been a flop, they had done well with two films starring David Essex, That’ll Be the Day (1973) and its sequel Stardust (1974) which together share some of the tone of Flame and also have cast and crew in common with it. It’s possible to overestimate Flame’s grittiness, when films like this were around. They often took advantage of higher BBFC certificates to include the sex and drugs which are almost entirely absent from Flame. It certainly falls short of what you could see in X-certificate fare like Permissive and Groupie Girl (both 1970), let alone Timothy Lea and his bare backside’s excursion into glam rock in Confessions of a Pop Performer (1975). Possibly recognising that a AA certificate (fourteen and over, which the Essex films were given) would exclude a lot of Slade’s fanbase, Flame went out with an A certificate, the equivalent of today’s PG, though it does push at the limits of that rating and is now a 12.

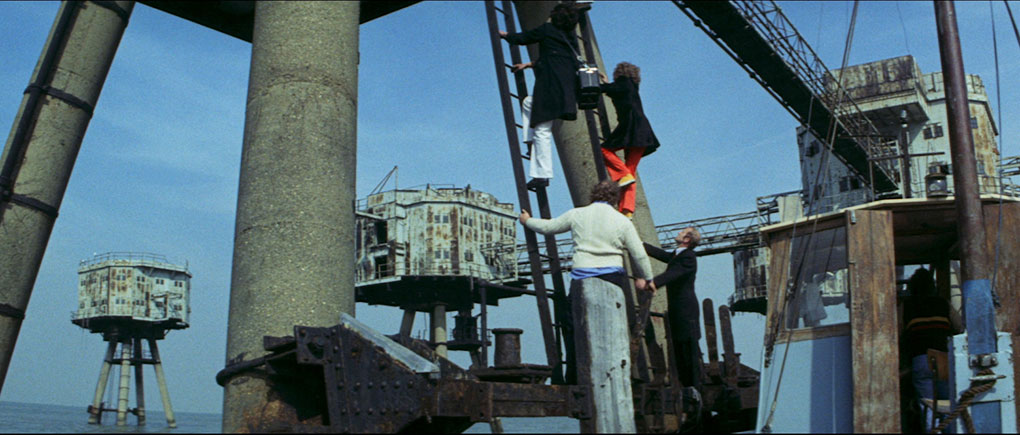

Flame was Richard Loncraine’s first feature film. He had a background in documentary, which stood him in good stead for the film’s realist approach. Loncraine and scriptwriter Andrew Birkin (who might have known something of pop music from his sister Jane’s stardom in the later sixties with her husband Serge Gainsbourg, in particular the much-banned UK number one single “Je t’aime...moi non plus”) followed Slade on tour in the USA to pick up authentic details. (Dave Humphries is credited for additional dialogue. He mainly added humour, according to Loncraine.) According to Noddy Holder in the interview on this disc, everything in the film really happened, if not necessarily to Slade – and that includes the scene where Flame are interviewed on a pirate radio station by DJ Ricky Storm (real-life DJ Tommy Vance) and someone starts shooting at them. The scene where Stoker, then in The Undertakers, is accidentally locked inside the coffin he’s singing from was based on a real incident with Screaming Lord Sutch. The film was shot on location in London, Nottingham and Sheffield, with the final scenes on the Brighton seafront. For much of the time, Loncraine’s direction is self-effacing, though he does allow himself some flourishes such as the opening shot, achieved with a crane.

The four members of Slade acquit themselves well on screen, with their on-screen characters clearly versions of their real-life selves. Don Powell needs particular commendation as the previous year he had suffered a horrendous car crash which had killed his fiancée and left him with short-term memory loss. His scene walking along a canal with his former boss (Patrick Connor) strikes the most poignant note in the whole film. Moving on to the professional actors, this was just Tom Conti’s second feature film. In his early thirties, he had previously concentrated on stage and television but had made his cinema debut a year earlier in the American Film Theatre film of Bertolt Brecht’s play Galileo. That had been directed by Joseph Losey, whose son Gavrik was the producer of Flame and had been associate producer on the two David Essex films. He plays band manager Robert Seymour with an unassuming upper-crust smoothness, in contrast to his Cockney hard-man predecessor Harding (Johnny Shannon). Shannon was an actor capable of greater range (he’s quite different and rather low-key in That’ll Be the Day) but he’s a little typecast here. In short he’s Harry Flowers from Performance again, if more on, but not entirely on, the right side of the law this time. Alan Lake has some good moments. The film is pretty much a male affair, but Sara Clee holds her own as Angie, girlfriend of Stoker and Barry at different times (a triangle is hinted at in the film but never really developed). Nina Thomas has rather less to do as Charlie’s wife Julie. Real-life television newsreader Reginald Bosanquet appears, uncredited, on Seymour’s television set.

Flame was shot in Scope by Peter Hannan, who has worked with Loncraine several times since. It’s in keeping with the downbeat feel of the film that his work is anything but glossy, looking like much of it done in natural light or a recreation of it, and not afraid to have details vanish into shadow at times, such as Harding’s face in the final scene. If the film had been made a decade earlier, so nearer to the time when it is set, you can easily imagine it being in black and white like its 1960s forebears mentioned above, quite possibly black and white Scope. Michael Bradsell’s editing enables the film to proceed at a fair clip, coming in at a bare ninety minutes. It could certainly have been longer, as half the running time is the band’s rise, with the peak coming suddenly and then the fall. Inevitably there was a soundtrack album and with it two singles. “Far Far Away” made it to number two, but “How Does It Feel” underperformed, reaching number fifteen, their first single to miss the top four since their first chart hit “Get Down and Get With It”. Many would now think it one of their best.

Opening in January 1975, Flame was not the hit that was hoped for, the after-the-fact rationalisation being that it wasn’t what the band’s fans really wanted to see. It made an undying fan of a certain young Mark Kermode, who was either eleven or twelve depending on when in 1975 he saw it. More of him below. Slade, unlike Flame, had quite an afterlife. They played the 1980 Reading Rock Festival, as last-minute replacements for Ozzy Osbourne, playing all the hits, which aren’t too far away from hard-rock songs if you add guitar solos. In fact, the then largely heavy-metal Reading crowd loved them. (In fact, some hard-rock bands have covered Slade songs.) This led to a brief return to the charts in 1984 with “My Oh My” and “Run Runaway”. The classic lineup of the band ended in 1992, though some members have continued to play in versions of the band since.

Slade in Flame is released in dual-format (Blu-ray and DVD) by the BFI. The discs are encoded for Region B and 2 respectively. This review is based on a checkdisc of the Blu-ray. The film had an A certificate originally but is now a 12.

The film was shot in 35mm with anamorphic lenses. The transfer, scanned and remastered from original 35mm materials, is in the intended ratio of 2.35:1. As mentioned above, this is intentionally not the most colourful film, some of Flame’s stage costumes apart, but those colours do look true and grain is natural and filmlike. Some darkly-lit scenes are, as also mentioned above, likely intentional. I saw this same restoration on a cinema screen a few weeks ago as I write this, and the Blu-ray transfer is true to that DCP showing. Although I’m of an age to have done so, I didn’t see the film on its original release and my only previous viewing was the Channel 4 broadcast in 1987.

Flame was about three years too early for Dolby Stereo, and it doesn’t appear to have had a four-track magnetic soundtrack even at showcase London cinemas. So everyone in 1975 heard it in mono, and that’s what’s on this disc, rendered on the Blu-ray in LPCM 2.0 and on the DVD in Dolby Digital 2.0 and there’s nothing untoward. Dialogue, sound effects and music are well balanced. English subtitles for the hard-of-hearing are available on the feature only, and I didn’t spot any errors in them. Usefully, they identify the songs we hear on the soundtrack, not just those played by Flame.

Commentary by Richard Loncraine and Mark Kermode

Given how much a fan of Flame Mark Kermode is – as he says, in the 1990s he went round much of the country with a 35mm print introducing showings of the film – it’s as well that he doesn’t dominate this commentary track as much as he might have done. Loncraine talks about how he became involved, meeting David Puttnam when he made a documentary for him. (That was the 32-minute Radio Wonderful, from 1973, about the early years of Radio One, with one of the DJs interviewed – Emperor Rosko – turning up in Flame. It did the circuit as support to That’ll Be the Day and would have made a good extra for this release if it had been licensed.) Kermode’s Flame geekery becomes ingrowing when he points out that The Undertakers’s song “This Girl” has different lyrics on screen to the version on the soundtrack album. Loncraine provides quite a few anecdotes of the film’s production, including the distinct lack of health and safety regulations in the scene where the band climb ladders out at sea to get to the pirate radio station located on a sea fort in the Thames estuary. Dave Hill was petrified by heights and had another issue in that he was bald, so his wig was in danger of being blown off. In fact, it was once, causing his scalp to bleed as it had been stitched in place. Loncraine is frequently self-deprecating and had been critical of this film, but he concedes that it’s “a better film than I thought it was”. An entertaining commentary.

Make Way for Noddy (9:04)

Clearly interviewed at the same time as his contribution to the BFI’s release of Eclipse, Conti is interviewed by an offscreen Vic Pratt. As indicated by the length of this interview, Conti doesn’t have a great deal to say about the film itself, though does point out that it wasn’t his cinema debut as many have supposed, but his second film. He wasn’t familiar with Slade’s music or any kind of glam rock for that matter: as he was born in 1941, it wasn’t his era. He found Alan Lake frightening and talks about how Lake might have been sacked from the film if it hadn’t been for his wife Diana Dors’s intervention. His lasting memory of Flame involves someone who wasn’t part of the film: Lynsey de Paul, whom he met at the premiere and who became a firm friend. He is clearly saddened by her death, which was in 2014.

Noddy Holder interview (53:31)

Recorded in 2002 for DVD release, this interview is excerpted in the making-of piece (see below), but this is the full version. Holder is interviewed by DJ Gary Crowley, but Crowley seems to have decided to ask a few prompting questions and let his guest talk. That’s very wise, as Holder is a natural raconteur. He accepts that he’s a better singer and musician than he is an actor, as witness the fact that it was some twenty years before he played another role (he doesn’t say so, but that was in the TV series The Grimleys). He was offered a part in a film with the Two Ronnies which was never made. The mechanics of filmmaking, including much hanging around between takes, was new to him and the rest of the band. However, he is complimentary about the others’ acting, particularly Don Powell’s given his memory difficulties at the time. He shares his memories of Alan Lake, Tom Conti and Johnny Shannon and concedes the mixed reviews* (Barry Norman’s on Film 75 was one of the few positive ones) and less-than-stellar box office.

The Making of Slade in Flame (58:25)

Produced for a 2007 DVD release, this is an oral testimony from all four band members, Tom Conti and Richard Loncraine (seemingly interviewed in his garden). Noddy Holder’s contributions derive from his interview by Gary Crowley above, so if you watch these items one after the other it will seem repetitive. Crowley and his questions are edited out, as is the case with the unidentified interviewers of the other participants. The piece is divided into ten sections, taking us on a chronological tour through the film, its production, release, the soundtrack album and the premiere. Given that Conti and Loncraine feature elsewhere on this disc, there’s inevitably some repetition in their anecdotes, but it’s an interesting if fairly standard run-through. Dave Hill wore a false beard to the premiere in a completely unsuccessful attempt not to be recognised. Loncraine says that Andrew Birkin (still with us as I write this, but not participating in this release) was “barking”, living in a house with a variety of skeletons and Halloween masks.

This Week: Men’s Fashions (4:52)

From 1973, roving reporter Michèle Brown tracks down Savile Row tailor Tommy Nutter, then a bright young thing of thirty, and we have plenty of views of the flash clobber on display. This was made for This Week in Britain, not to be mistaken for This Week, the ITV current affairs series which ran from 1956 to 1978. This Week in Britain was a magazine programme made by the Central Office of Information for distribution to overseas cinemas and television channels between 1959 and 1980. It was made in black and white until shortly after this item, going into colour when most overseas broadcasters had upgraded. You can imagine the makers would have liked to have shown off the hues on display in Mr Nutter’s boutique.

Original trailer (1:56)

2025 reissue trailer (1:14)

Trailers then and now, the latter with the benefit of hindsight of fifty years’ reputation, so it’s a little shorter and can add review quotes. The original trailer dates from a time when coming attractions only had U or X certificates, regardless of the actual certificate of the film itself. So a few words are bleeped out in 1975 but as one of the scenes is included in the 2025 version, our ears are not spared “bloody”.

Slade in Frame (2:12)

A self-navigating image gallery, including stills (mostly colour but some black and white), front-of-house cards, the soundtrack LP and even a promotional tie, of the kind you’d wear round your neck.

Booklet

The BFI’s booklet, available in the first pressing of this release, runs to twenty-four pages plus covers. After a spoiler warning, it begins with an essay by Graham Rinaldi, who was a fan from the outset at an even younger age than Mark Kermode. He was nine and had been given the soundtrack LP for Christmas. After this personal touch, Rinaldi goes through the inception and making of the film, and its rather mixed reception. Don Powell had to remind fans that Slade were playing characters and they liked each other a lot more than the members of Flame did. Nine-year-old Rinaldi admitted to being a little confused by that. He also reveals that a sequel called Down in Flames, with the band reduced to playing on ferries, was considered but never made.

This is followed by “Look Wot They Dun: A Potted History of Slade” by JT Rathbone, which begins by saying that unlike some of their contemporaries, the band doesn’t feature much in best lists for the 1970s. The band began in 1966 with Hill and Powell recruiting Jim Lea to become part of what was then called The N’Betweens, with Noddy Holder replacing the original singer later that year. Their first album, Beginnings, was released in 1969 when they became Ambrose Slade, reputedly after a secretary’s names for her handbag and shoes respectively. Chas Chandler signed them following a live performance, dropped the Ambrose and, despite an early skinhead image, the pieces were in place and encouraged Holder and Lea (lyrics and music respectively) to generate their own material, the first charting single here incorrectly given as “Get Down With It”. Rathbone’s piece inevitably concentrates on the 1970s, including their later-decade commercial decline and ending with their revival fortunes after Reading in 1980.

“Britain and the Beat: UK Pop Music Films in the UK” by Barry Forshaw begins by pointing out that some notable directors made pop/rock movies, Richard Lester, John Boorman and Peter Yates among them. He goes back earlier in the decade with Cliff Richard’s films such as The Young Ones (1961) and Wonderful Life (1964), both directed by Sidney J. Furie before he made The Ipcress File, also taking in the earlier Expresso Bongo (1959), which had Val Guest at the helm. There was also Beat Girl (1960), which added sex and an X certificate into the mix. But the turning point of the genre was Richard Lester’s films with The Beatles, A Hard Day’s Night (1964) and Help! (1965). Lester also made It’s Trad, Dad! (1962) with the less of-the-moment Craig Douglas and Helen Shapiro, while Boorman’s eye-catching visuals in Catch Us if You Can (1965) did something to disguise the fact that the Dave Clark Five were no Fab Four (or indeed Five). The Rolling Stones were the biggest act not to make a film, even if Mick Jagger started an acting career with Performance. The rock film really peaked in the 1960s, with Flame being a later example, set at around the time of its apex. As the 1970s went on, you were more likely to see concert films, such as Led Zeppelin’s The Song Remains the Same (1976) and films taking on the spirit and some of the music of punk, such as Jubilee (1978) and The Great Rock ’n’ Roll Swindle (1980). As of his writing, Forshaw suggests, the British pop/rock film might well be dormant, but maybe these things are cyclical and who knows what may come?

The booklet concludes with a cast/crew listing and notes on and credits for the extras.

Given mixed reviews at the time, and a commercial disappointment, Flame has grown in stature over fifty years. While it’s a good film, I’d suggest it’s now become a little overrated. No complaints about the film’s restoration and presentation on this dual-format release.

* For the record, the back cover of the March 1975 Monthly Film Bulletin shows that five out of six newspaper/magazine critics of the day (Nigel Andrews of the Financial Times, John Coleman of the New Statesman, Derek Malcolm of The Guardian, Chris Petit of Time Out, Alexander Walker of the Evening Standard) gave the film one star out of four, with only Margaret Hinxman of the Daily Mail giving it two. Tony Rayns’s review in that issue isn’t favourable either.

|