|

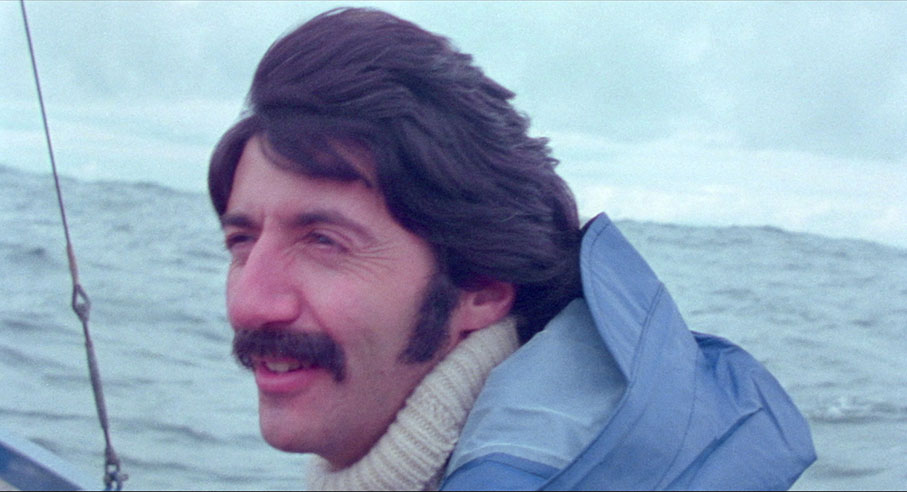

The credits appear over a Scottish beach as a man’s body is washed up, a bloody injury to his head. This is Geoffrey (Tom Conti), who had been out on a boat the night before with his twin brother Tom (also Conti, without the moustache he has as Geoffrey) to observe a total lunar eclipse. There is an enquiry, and Geoffrey’s death is put down to accidental drowning. Later, Tom goes to what was his childhood home on the coast to spend Christmas with Geoffrey’s widow Cleo (Gay Hamilton) and their nine-year-old son Giles (Gavin Wallace). However, as the holiday break progresses, things go wrong and tensions are bared.

Based on a novel by Nicholas Wollaston and written and directed by Simon Perry, Eclipse is on the surface a psychological thriller – what was the real cause of Geoffrey’s death? – but it’s a film of subtle nuances and hints, which doesn’t go in directions you might expect. It didn’t do much business on its cinema release in 1977 and has been virtually unseen since then, until now. You can see why: it’s an essentially arthouse film which rather fell through the cracks, commercially speaking. Maybe it would have done better, in arthouse terms, if it had been in a foreign language. However, box office success or failure often don’t correlate with quality, or lack of it, and neglected but interesting British films like this are the very thing the BFI’s Flipside line is there to bring to wider attention. Watching it now reveals a very intriguing, if certainly slow-burning, film that relies on the viewer to pick up small details and to an extent leaves some of its events open to interpretation.

Eclipse was the second, and as it turned out final, production of London-based Celandine Productions. The first was Knots (1975), a 69-minute film of Edward Petherbridge’s play inspired by popular psychiatrist R.D. Laing’s book about the “knots” that impede human communication. Laing himself appears in the film as “man watching rehearsal”. Knots was written and directed by David I. Munro and produced by Simon Perry. With Eclipse the two men swapped roles. Eclipse was made on a small budget raised via private investment and was shot in 1976 (its copyright year) on location in Sutherland and Caithness, in the north of the Scottish mainland. The film has a credited cast of just seven, and after ten minutes, when Tom arrives at Cleo’s house for Christmas, there are just three actors on screen until the end of the film, other than in the closing minutes a brief long-shot glimpse of a lighthouse keeper (Patrick Cadell, a unit runner on Knots and for most of his career an assistant director) and a flashback to a woman (Jennie Paul) walking her dog on the beach and finding Geoffrey’s body.

There’s a scene around the halfway mark of the film where Tom cooks the turkey for Christmas dinner. However, despite having had it on the right temperature and cooking time, it’s undercooked, almost raw in fact, and cold inside. You have to wonder how much this is a metaphor for Tom himself, who doesn’t seem to be mourning his brother much, and in fact was often in his shadow as the younger sibling by some twenty minutes. And that’s before he confesses to something many would find unforgivable (animal lovers be advised), though Cleo doesn’t react much to this revelation. For most of Tom’s life, he’s wanted to be separate from his twin, to do things to show that he is not Geoffrey. How much can his account of the accident – which we see in several flashbacks, jaggedly cut into present time – be trusted and is he missing something out? In the end, we do have a solution, but it’s still open to doubt. Meanwhile, he’s not the only person who might be unreliable. Cleo has on display her full-frontally-naked painting of Geoffrey, but, Tom says, it’s a lie – Geoffrey’s build is bigger. It’s implied that the build of the man in the painting is closer to Tom’s (even if it is the same actor playing both roles). Tom asks for the painting to be put away while he’s in the house, and later in the film he does that himself. Closeness and separation are often in play. In a flashback Geoffrey says that he sees Giles as a continuation and extension of himself, one to carry on where he leaves off. Maybe he is, or is Tom’s calling Giles “Geoffrey” at one point just a slip of the tongue? The past constantly intrudes into the present, with Perry often intercutting between the two, such as a present-day conversation between Cleo and Tom with a distraught Tom returning from the accident to break the news to Cleo of Geoffrey’s death. It’s a credit to Perry’s writing and direction, and the editing of Norman Wanstall, that these transitions are always clear.

As the film is a three-hander for almost its whole length, a lot is down to the cast, and Conti give strong performances. Conti was becoming a star at the time, with his role on TV in The Glittering Prizes being a highlight of his career to date: he made Eclipse during a gap in his schedule for that serial. Gay Hamilton had a screen career from 1961 (the year she turned eighteen) and her last credit on IMDB is from 2017, but she didn’t play many lead roles, so she makes the most of this. This is Gavin Wallace’s only screen credit: he was genuinely nine years old at the time of shooting. He gives a capable performance, if all his line deliveries are at the same high pitch. The only other speaking roles are played by Scottish-based character actors Paul Kermack and David Steuart, in the enquiry scene near the start.

This was Simon Perry’s only film as director. After this, he returned to producing with the Film on Four Another Time, Another Place (1983, and another film now little-seen deserving further attention) and the 1984 version of Nineteen Eighty-Four. In the 1990s he ran British Screen, a national funding body for new British film productions. In ten years the organisation funded some 140 films, including The Crying Game (1992) and work by Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. Eclipse was all but unseen after 1977. It was never released on video or DVD and as of this writing has not had a showing on British television. There are many British films of the time which have been forgotten, not least because of simple lack of availability. This Blu-ray release enables it to have some attention which it merits.

Eclipse is BFI Flipside number 51, released on a Blu-ray encoded for Region B only. The film was rated AA (over-fourteens only) on its cinema release and is now a 15. The short films The Chalk Mark and Marooned were 15 and 12 respectively on their cinema releases and retain those certificates on disc. The public information films are exempt from certification but wouldn’t get higher than PG, if that.

The film was shot in 35mm colour and the Blu-ray transfer is in the intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1. This transfer was derived from a 2K scan of the original 35mm negative held by the BFI National Archive. The colour scheme is quite muted, with few bold hues, and the transfer is a little soft. In the commentary, Vic Pratt says that technical producer Douglas Weir is familiar with the Queen of Kylesku ferry (seen two minutes in) and based the colour-grading on the actual colours of the boat and the crew’s waterproofs. So I have to take this as accurate, not having seen the film before. Grain is natural and filmlike.

The soundtrack is the original mono, rendered as LPCM 2.0. Nothing much to say, with dialogue, sound effects and Adrian Wagner’s music score clear and well balanced. English hard-of-hearing subtitles are available for the main feature only.

Commentary by Vic Pratt

Vic Pratt, cofounder of BFI Flipside, begins by describing how this release came about. His interest in Eclipse came from the interview he did with Tom Conti for the Heavenly Pursuits release. Conti asked after the film as it was one of the few of his of which he didn’t have a copy. However, the BFI National Archive held picture and sound negatives, so a reference copy was made and Pratt watched it, deciding that it was the sort of film he was seeking out for the Flipside line. Eclipse might not be a long film (86 minutes) but given the limitations of the setting and the small cast, there is a lot of space to fill, so Pratt goes into some depth about the careers of the two leads (less so young Gavin Wallace) and of Simon Perry. Much of the rest of the commentary is quite scene-specific, though this is more to discuss themes and nuances as they arise than simply describing what’s on screen.

Sun and Moon: Tom Conti Discusses Eclipse (9:47)

Interviewed by an offscreen Vic Pratt, Tom Conti talks about his role in Eclipse. At the time he was making The Glittering Prizes, in which he played effectively a stand-in for author Frederic Raphael. However, the six-part serial is an odd one as it’s effectively an ensemble piece, with some lead characters only appearing in single episodes and other leads absent for one or more. Conti plays the lead in three episodes and is in a fourth briefly, so he had a two-month gap in his schedule in the middle of production, and that’s when he made Eclipse. The theme of drowning was a little close to home, as he had almost drowned on a film he appeared in with Rod Steiger. (He doesn’t name the film, but that would be That Summer of White Roses (1989).) In the scene with the Christmas turkey, the one brought in for the production had been left out long enough to become putrid and smelled foul, and as a result Conti didn’t eat turkey for many years afterwards. He feels that everyone, including Simon Perry, were feeling their way as they made the film. Conti speaks warmly about Gay Hamilton, whom he had known at drama college. There are some clear memory lapses, which are understandable given the lapse of time since the film was made. You can hear Pratt prompting him occasionally, but Conti says, “You’re lucky I can remember anything about it!”

Relative Strangers (44:50)

As ever on a BFI release, there are short films from the archive which aren’t directly connected to the main feature, but are tangential to some of its themes. These two, both made with the involvement of the BFI Production Board, both concern, in the words of the booklet, “childhood and its inevitable estrangement from adulthood; the ever-mutating peculiarity of familial connections; and the importance of small, seemingly insignificant details on larger life narratives”. Both short films also have, like the feature, Scottish settings. There is a Play All option.

The Chalk Mark (24:20)

Made in 1989 by the BFI in association with Channel Four, this short is a semi-autobiographical piece by writer/director Bernard Rudden, his debut in both roles. It was made as part of the BFI Production Board’s New Directors initiative. Set in Glasgow, it’s a series of episodes rather than a plot, centering on various members of a family, mainly a young boy (Michael Murray). But we also see his grandmother (Jean Faulds) and his parents (Maggie Macritchie and Laurie McNicoll). Shot in 16mm, it’s presented in an aspect ratio of 1.33:1 with mono sound (LPCM 2.0).

Marooned (20:29)

From 1992, written by Dennis McKay and directed by Jonas Grimås, Marooned is set in a mainline train station, particularly in the left-luggage office manned by Peter (Robert Carlyle). He spends his days observing the people who come and go outside, putting together stories from the glimpses of their lives he sees and hears. He is also given to opening the luggage left in his trust and seeing what is inside. In particular he has become obsessed with Claire (Liza Walker) and finds he has unexpected connections with her. A slightly elusive story, anchored by an often-silent performance by Carlyle. Marooned was nominated for the BAFTA Award for Best Short Film. The credits acknowledge the help of Scotrail who point out that luggage is not opened other than in exceptional circumstances. Shot in 35mm, this is presented in a ratio of 1.66:1 and the original Dolby Stereo soundtrack is rendered as LPCM 2.0, playing in surround.

Not Waving, Drowning (4:30)

Another batch of short films, again with a Play All option. This time, we take three brief looks at the dangers of open water.

Joe and Petunia: Coastguard (1:38)

It was a question on Pointless once to see if you can name the emergency services available in the UK if you call 999. Just about every one of the one hundred members of the public asked by the programme knew ambulance, fire and police, but would you have known for example mountain rescue, cave rescue or indeed, as in this case, coastguard? That’s what this short animation from 1968 aims to raise your awareness of. Joe and Petunia sit on the beach, he with a handkerchief on his head, she with sunglasses and eating an ice cream. But what’s happening with the man in the dinghy Joe can see through his binoculars? Why is he in the water and waving at them?

Charley Says: Falling in the Water (1:13)

Charley is a cat, in this animation from 1973. A young boy tells how he and Charley were having fun with puddles, but then Charley made a big jump and landed in the river. Spoiler: the cat doesn’t die. When you go near the water, do make sure you keep close by a grown-up.

Lonely Water (1:37)

Lonely Water, made in 1973, has been on other BFI discs, for example the Best of COI [Central Office of Information]: Five Decades of Public Information Films two-disc Blu-ray compilation released in 2020. It shows that public-information films were not afraid to use shock tactics. Even something as short as this packs a lot in its minute and a half. The black-robed figure of Death (voiced by Donald Pleasence) oversees children playing by a lake, watching as unwary children fall into the water, one show-off sliding in while another unwary child falls and drowns. Sensible children escape Death’s clutches to his regret, but Death signs off with a sepulchral “I’ll be back”, a different kind of Terminator before the fact.

Trailer (1:26)

This isn’t an original trailer, as none exist (presumably one was made, though). So this is a newly-prepared trailer, though it does begin with a period-appropriate BFI ident. The trailer aims to intrigue and does, though no doubt in 1977 this film was a hard sell.

Image gallery (1:42)

A self-navigating gallery comprising the original novel’s dust-jacket, black and white stills and two lobby cards.

Booklet

The BFI’s booklet, available with the first pressing of this release, runs to twenty-four pages plus covers. Vic Pratt, with a spoiler warning, leads off with “Unreliable Narrations: Eclipse”, taking the scene with an undercooked turkey, halfway through, as a metaphor for the whole film: “half-raw...cold at heart”. After a brief account of the film’s production and some of its fleeting cinema release, Pratt’s essay talks about the themes and style, and the intentional ambiguities, at times with comparisons to the original novel. Inevitably this overlaps to an extent with Pratt’s commentary track. He sees the film as something of a foreshadowing of Enys Men, another BFI release set in an isolated coastal location, though Cornwall rather than north-east Scotland.

Eclipse didn’t entirely vanish after it left UK cinemas in 1977, as the next item is based on an interview which accompanied a screening in the (unspecified) early 1980s. Here Simon Perry talks to Clive Hodgson about the film, its setting up (after Knots was shown at Cannes in 1975) and its financing to the tune of £59,000 largely from individuals. He also talks about Celandine projects which didn’t come about. At the time he wanted to be a director but decided he was better as a producer.

Douglas Weir contributes “The Locations and Landscapes of Eclipse”. As a Scot, he is qualified to comment that there are a few geographical liberties taken, with locations further apart than they are meant to be in the film itself. So we have Dunnet Head Lighthouse, the northernmost point of the Scottish mainland. The beach in the opening scene is a mixture of two actual beaches, but the ferry we see early on runs between Skye and Glenelg. Elsewhere, Cleo looks out of a window to see Tom and Giles in a boat...in a loch actually three miles away. However, he says, many of the locations are largely unchanged nowadays, nearly fifty years later.

After a cast and crew listing, there is a reprint of John Pym’s review of Eclipse from the March 1977 Monthly Film Bulletin, plus notes on and credits for the special features. Flipside co-founder William Fowler writes about The Chalk Mark and Marooned.

A subtle, ambiguous film, Eclipse won’t be to all tastes and certainly wasn’t when it played in British cinemas back in 1977. For many people this Blu-ray release will be their first opportunity to see it, as was the case for me. But the whole remit of BFI Flipside is to give some attention to neglected films like this and as such this release succeeds.

|