|

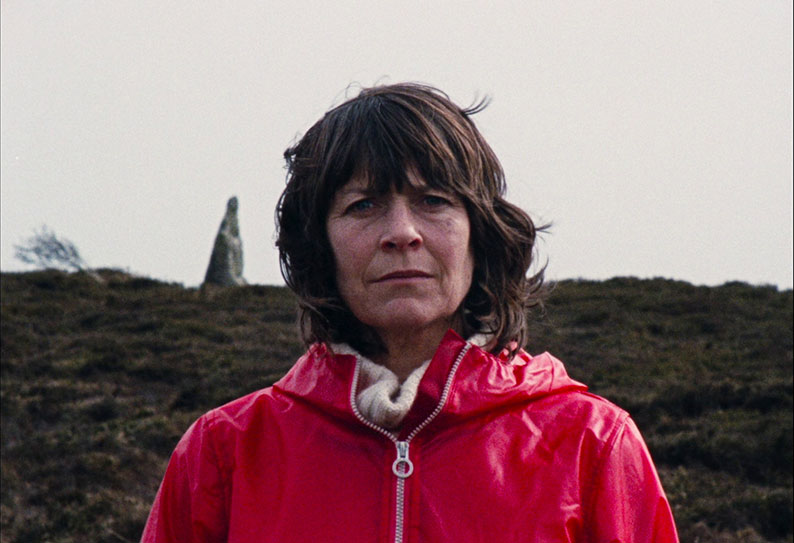

April 1973. On an island off the Cornish coast, a woman (Mary Woodvine), not named and listed in the credits as The Volunteer, is alone, there to monitor some unusual flowers growing there. Day after day, there is no change for her to record in her logbook. Her day-to-day activities – walking round the island, dropping stones down an old abandoned mineshaft, tending to the petrol-driven generator that gives her electricity, listening to the radio while eating or drinking several cups of tea – give her life its structure. She hardly sees anyone other than the man who delivers her supplies by boat. However, strange things begin to happen, and she begins to see visions centring on a large rock, visions of miners, singing children, a young woman (her younger self?). As May Day, the anniversary of a local lifeboat disaster, approaches, changes begin to happen in the flowers...

Cornish filmmaker Mark Jenkin came to prominence with Bait (2019). That was as much due to its subject, dealing with tensions between locals and incomers in a fishing village, the latter buying up property and pricing out the former, as with his filmmaking methods. Bait was shot on 16mm with a clockwork Bolex camera which wasn’t set up for synch sound, so the entire soundtrack was created later. Jenkin also personally processed the film, and occasional imperfections, such as scratches and spots and instances of light bleed, became part of the hand-made aesthetic. Enys Men follows much the same process except that instead of being in black and white, it’s in colour, so processing was done elsewhere. (The title is Cornish for “stone island” and is pronounced “ennis mayne”.) The lead role is played by Mary Woodvine (Jenkin’s partner), who had a supporting role in Bait, while second-billed as the supply boatman is Edward Rowe, who played the lead in the earlier film. Also in the film is Mary Woodvine’s father, John Woodvine, ninety-one years old at the time of production and five years after his previous screen appearance.

Those similarities are considerable – after just these two features, it’s hard to mistake Jenkin’s work for anyone else’s – but they do end. Bait is a contemporary-set drama but Enys Men is a period piece, set specifically in 1973, though that time setting does become elastic, of which more in a moment. Enys Men is less easily classifiable, but it does contain elements of folk horror and is a ghost story of sorts. That folk horror comes from the film’s, and its maker’s Cornish heritage, a part of the country with its own ancient language and almost an island with the river Tamar not quite cutting it off from the rest of the English mainland.

The film is also horror of a specific kind, that of the breakdown of reality. As the story progresses, the Volunteer, and we, begin to see things on the isolated island she is residing on, her only human contact over the radio and the visits of a supply boat. Given that for much of the film there is only one person on screen, dialogue is sparse, so for much of the time Jenkin is showing rather than telling, and often doing so by means of editing. People – a man, a young woman, some girls singing (the Cornish-language song “Kan Me”, which is also performed by its composer, Gwenno, during the end credits) – appear without warning. The flower which the Volunteer is studying begins to grow a strange lichen, which, she soon finds, is growing on her too. Time becomes fluid. Nicolas Roeg is an avowed influence, and not just because of the Volunteer’s red jacket recalling Don’t Look Now, but because of the editing, with Jenkin taking after Roeg’s characteristic use of sometimes free-associative cross-cutting in time and space, which also featured to some extent in Bait. Some of what we see may be flashbacks or premonitory flashforwards. There’s also a flashforward on the soundtrack as a radio announcer refers retrospectively to something which happened on 1 May 1973, when we know from the Volunteer’s logbook that we are in April of that year. In the extras, Jenkin also acknowledges fellow Cornish resident Lawrence Gordon Clark, director of all but one of the BBC Ghost Stories for Christmas in the 1970s.

Enys Men is an open text which doesn’t explain itself and allows you to form your own interpretations of it, which may be entrancing or infuriating according to taste and sensibility. Pace is measured, even for a not-especially-long film as this, and to my mind after two viewings it is over-extended. However, it confirms that Jenkin is one of the most distinctive filmmakers working in the UK at the moment.

Enys Men is a dual-format release from the BFI, comprising a Region B Blu-ray (a checkdisc of which was supplied for review) and a Region 2 PAL DVD, Enys Men has a 15 certificate. Haunters of the Deep was a U certificate on its original release and retains that rating on disc. The Duchy of Cornwall is a documentary which has been exempted from certification, but carried a U on its cinema release in 1938.

Enys Men was shot on 16mm colour stock. The Blu-ray is in the non-standard aspect ratio of 1.45:1, though that wouldn’t be an issue for cinema showings via DCP. (I suspect that 35mm prints – at least one was in circulation – would have been shown in 1.37:1 with thin black bars at top and bottom, but I didn’t see such a showing.) The transfer has plenty of grain, as you would expect from its 16mm origins, and some of the colours, reds especially do pop, due to stopping the camera down and pushing the film during processing. The result is a vibrant look with strong primary colours, the blue of the sea and the red of the Volunteer’s jacket and that of the generator. As I say above, occasional splices, scratches and light bleed are not bugs but features of this film.

The soundtrack is available in both DTS-HD MA 5.1 and DTS-HD MA 2.0, which plays in surround. Jenkin mentions in the disc extra that his original idea was to mix the film in mono (which would have been period-appropriate for 1973) but thought that was too thin. For much of the film, the soundstage is mostly in the front speakers, with surrounds used for ambience, but occasionally there is more use of those surrounds, for example a helicopter near the end of the film. Certainly the dialogue (all post-synchronised, along with the rest of the soundtrack) is clear and integrated with sound effects and Jenkin’s score and some diegetic music. Given the sparsity of dialogue, the soundtrack carries a lot of weight. I played the 5.1 track and sampled the 2.0, but there isn’t much difference between them, so play which is most appropriate for your set-up. English subtitles are available for the main feature only, and there is also an audio-descriptive track in Dolby Digital 2.0.

Commentary with Mark Jenkin and Mark Kermode

At the start of this commentary track, Mark Kermode lays his cards on the table: Bait was his favourite film of its year and Enys Men is a masterpiece (which he has watched several times now) and will no doubt be one of his favourites of this year. Jenkin takes us through the inspirations and making of the film but what he doesn’t do is explain it, and Kermode specifically doesn’t ask him to. That said, he does talk a lot about the themes of the films, such as the coexistence of past and present and future, but some of the non-linearity is due to making use of what he had available when he came to edit the film. He says the reason the film is set in 1973 is a frivolous one, simply because he liked the look of the year when written down. (It’s not Mary Woodvine’s hand we see writing in the logbook, by the way: her hand double was assistant director Callum Mitchell.)

Mark Jenkin and Mary Woodvine in conversation with Mark Kermode (28:49)

Dr Kermode again, with a Q&A after a screening of Enys Men at the BFI Southbank in December 2022. This showing was from a 35mm print and Jenkin leads a round of applause for projectionist Steve. Inevitably much of this overlaps with other extras, but it’s a worthwhile listen. Mary Woodvine’s memories of the shoot sometimes conflict with Jenkin’s, such as the scene where she is singing along via one word to the radio. She also tells how Jenkins shouted “blank faces!” for the scene where she is disco-dancing with Edward Rowe. Questions from the audience appear on screen as text captions.

Film Sounds (86:07)

The sound department is an often overlooked part of a film crew, so an item like this is invaluable. Mark Jenkin and fellow filmmaker Peter Strickland have a discussion on the processes and use of film sound, moderated by the BFI’s Douglas Weir, which took place at the BFI Southbank in January 2023. Strickland is a good choice for this discussion, as his own films have used sound in striking ways: it’s almost the entire subject matter of Berberian Sound Studio, for example. He has also directed radio plays, including an adaptation of Nigel Kneale’s TV play The Stone Tape, and he talks about this. Jenkin sometimes had to be resourceful, recording John Woodvine’s part on an Iphone, for one. The two talk about the possibilities of multi-channel sound and, at appropriate times, silence. Jenkin also talks about presenting Bait with a live score, and his plans for doing the same with Enys Men.

Normally with items like this, film extracts shown are edited out for licensing reasons, but in this case they’re kept in: scenes from Enys Men and Strickland’s Flux Gourmet as well as the six-minute shot of Jenkin at work on the Enys Men soundtrack (see below). To make use of these clips, this item is available in a choice of two soundtracks, Dolby Digital 5.1 and 2.0. As with the Q&A above, questions from the audience appear on screen as text.

Haunters of the Deep (60:58)

The BFI have released several Children’s Film Foundation short features, and short shorts as well, on DVD, including so far four Bumper Box sets (volumes 3 and 4 reviewed by me for this site). No doubt commercial considerations mean that they don’t release these sets on Blu-ray but once in a while a CFF (or in this case CFTF, as the organisation had become the Children’s Film and Television Foundation by then, namely 1984) production crosses the divide and appears in HD as a Blu-ray extra. In this case, it’s because Haunters of the Deep was made in Cornwall, on some of the same locations as Enys Men, old tin mines included, and Mark Jenkin specifically identifies the film as an influence on him. He showed it during his BFI Southbank season of some of the influences on Enys Men.

Haunters of the Deep in many ways follows the template of many other CF(T)F films, with youngsters of both sexes so as to appeal to both sexes in the audience. American Becky (Amy Taylor) is in Cornwall with her father (Bob Sherman), president of a mining company in negotiations to reopen an old tin mine. Left to her own devices, Amy meets local lad Josh (Gary Simmons), who has seen visions of a boy (Philip Martin) who speaks to him in Cornish. Meanwhile, Amy and Josh meet Captain Tregellis (Andrew Keir) who warns that reopening the mine will lead to disaster.

Given the intended audience, Haunters of the Deep is less enigmatic and less “open” than Enys Men, resolving itself quite neatly. Yet along the way, writers Andrew Bogle (who also directed), Tony Attard and Terry Barbour, conjure up a potent atmosphere of strangeness, with the past leaking into the present, and history repeating itself. The three children didn’t go on to adult acting careers: Amy Taylor has two other IMDB acting credits, and this is the only film for Gary Simmons and Philip Martin. However, Simmons had a more extensive career on stage as a child actor and later entered the music industry as one half of Taste of Honey (later called Legacy) with his brother.

Recording the Score (5:56)

A static single shot, in black and white, of Jenkin in his studio recording the film score, using tape loops and a small synthesiser keyboard. There’s no other information so this doesn’t tell you very much, but I refer you to the “Film Sounds” item, during which this shot is played and Jenkin effectively gives a live commentary on it. That does rather make this item superfluous.

Mark Jenkin’s audio diaries (90:10)

Jenkin recorded these while he was making Enys Men, and they were broadcast in short instalments on BBC Radio 4’s now-defunct The Film Programme. They have been edited together for this release – you can tell the joins from changes in ambience – and play as an optional audio track on the main feature. There’s a lot of detail here about the whys and wherefores of low-budget filmmaking, including the challenges of film production during a pandemic. Towards the end, he is joined by Mary and John Woodvine. The latter shot his scenes at the end of principal photography – partly because they had to wait for him to receive his second Covid vaccination – and his presence made the crew less demob-happy than they might have been.

The Duchy of Cornwall (14:57)

A short travelogue from 1938 taking us round the county, with many of the sights on display, including St Michael’s Mount and Tintagel, King Arthur (via ancient manuscripts) and those tin mines and fishing villages. No doubt this served as an advertisement for tourism to the far South-West, whether actual for those near enough or well-off enough to go there (some of whom we see sunning themselves on the beach), or vicarious for those who were not.

Image gallery (2:01)

A self-navigating gallery of nine production stills, including some of Jenkin with his camera, and ten film stills.

Theatrical trailer (1:28)

A suitably enigmatic glimpse at a film which you can’t imagine would be too much of an easy sell, including some of Jenkin’s trademark film scratches. The soundtrack can be played in DTS-HD MA 5.1 or DTS-HD MA 2.0, just like the feature.

Booklet

The BFI’s booklet, available with the first pressing of this release only, runs to thirty-two pages. It begins with a spoiler warning. It begins with Mark Jenkin’s director’s statement, revealing that his starting point was a memory of visiting the Merry Maidens, a stone circle near where his grandmother lived in West Penwith. Legend has it that the stones, nineteen of them, were girls punished for dancing on a Sunday by being turned into stone. The two pipers who had led the girls astray were also petrified, a little further away But what, young Jenkin asked himself, what if the stones were actually alive? People had detected horror elements in Bait and his earlier short Bronco’s House so he decided to make his own horror film. The Cornish legends and landscape inspired him, and he wrote the first draft of the screenplay in longhand over three nights.

Tarah Judah is up next, with “A Blueprint for Survival”, which is also the title of the (genuine) book that the Volunteer is reading, and in part, she suggests, a blueprint for the protagonist’s situation. (It was one of the first eco-themed bestsellers, and is in the film because Jenkin found it on a Google search.) Judah’s essay elucidates the film – though, with this one, your interpretation may differ – pointing up the use of ritual elements and the view of the natural world from which the film’s stranger elements erupt.

Rob Young follows with “A Mayday for Mayday”. Young is the author of the excellent book The Magic Box: Viewing Britain Through the Rectangular Window, which covers a lot of the bizarre and otherworldly television many Britons of a certain age (like myself) watched in their childhood, including a lot of what would now be called folk horror. That’s where the emphasis of this essay lies, with Young linking Enys Men not only to such as Robert Bresson’s L’argent (paid tribute to in the opening shot, as Jenkin has said) but to those Ghost Stories for Christmas as The Signalman and also Stigma, which also features a stone circle. That was, Young suggests, a time when unconventional narrative techniques could be used in television drama if it still delivered the horror goods, and also mentions David Rudkin’s three-hour Artemis 81 – shown only once, and the now-out-of-print DVD goes for high prices – which has baffled viewers ever since. Young points out that the year when Enys Men is set, 1973, was a significant one for British horror, seeing the release of The Wicker Man and Don’t Look Now (on a double bill) and The Stone Tape had been broadcast on the previous Christmas Day. He picks out some influences and references in Enys Men, from Blood on Satan’s Claw to The Shout (shots of the Volunteer and the Boatman screaming) and those public information films which traumatised a generation of schoolchildren, and details some of the film’s time slippage: not only the radio announcement from the future mentioned above but also twenty-first-century music playing over that radio.

William Fowler contributes “Counting the Ways”, which is subtitled “Eleven Incomplete, Uncertain, Sometimes Contradictory Thoughts About Enys Men and its Relationship to Experimental Film”. As that subtitle indicates, this is in eleven subsections and Fowler tackles the films use of folk-horror elements but also its subversion of our expectations and its breakdown of a conventional narrative. Fowler pays attention to the film’s editing and its effects on its use of time and place, and its use of a female protagonist “[watching] herself being looked at” and “[looking] at herself being watched”. He also talks about Jenkin’s hand-crafted, almost artisanal approach to filmmaking.

Most disc booklets have just the one essay directly about the film itself, but Enys Men has generated four. It’s a tribute to the film that they are able to take different approaches to the same hour-and-a-half-long feature. Jason Wood contributes “Vice. And Versa.” (That’s the poster tagline for Performance, another film of identity breakdown, co-directed by Donald Cammell and Jenkin’s avowed influence Nicolas Roeg. Jenkin included Performance in his top ten for the 2022 Sight & Sound Greatest Films of All Time poll.) In the BFI season he curated, of some of the influences on Enys Men (its DNA, as he put it), Jenkin showed Roeg’s first solo feature, Walkabout, which was the first Roeg film he ever saw, possibly because it was the only one of Roeg’s great run in the 1970s and first half of the 1980s which wasn’t adults-only. Wood compares Jenkin to Roeg in several ways: as a director who is also his own cinematographer (as was Roeg on his first two films, after his previous career as a leading DP of the 1960s), in their use of editing to fragment time and space, and their use of landscape. However, Wood suggests, the success of Jenkin’s films may be because they are of their time and not ahead of it, as Roeg frequently was, his films moving from initial incomprehension for the most part and rising in stature over the years.

These essays are followed by film credits and notes on and credits for the extras, including an extended note on Haunters of the Deep by Vic Pratt.

Following on from the relatively straightforward, but with moments of strangeness, Bait, Mark Jenkin has made a fascinating, often puzzling film, crossing folk horror with experimental film, a film which will reveal its mysteries over more than one viewing. I commend the BFI’s release not just for what it contains on the discs themselves, but also for a booklet which you should ensure you get by buying one of the first pressing of this edition.

|