| |

“And suppose the studio suggests hiring someone else, or they start working on another project and are no longer available, then I don’t do the movie. But if it works out and I get who I want, then the actors are the most important people to me, because they are the ones in front of the camera the whole time. You can see their psychology, their emotions, what they give in a scene, is like the birth of life, the most important magical moment.” |

| |

Film Talk interview with director Barbet Schroeder* |

I was going to open with “We’ve all been there,” but I’m not sure that’s as true as I suspect. Some of us then, perhaps. Being gaslit and manipulated by someone we regard as a friend or a lover is a uniquely excruciating experience. Constantly gifting the benefit of the doubt is like ambrosia to the manipulator. The nicer and more accommodating the victim, the longer it takes to arrest the personal control that’s being stripped from them. Amplify that control, add a dash of psychosis and ramp that up to eleven and you have a superior thriller with real tension and surprisingly frightening moments courtesy of Single White Female. If, in this day and age, we could gingerly sail past the embedded racism in the title, it’s best to explain that the SWF acronym came about, like a great many things, to save money. There were common abbreviations used in newspaper ads just to save a few cents here and there. The problem is not self-identification of course, but specifically asking for the same to apply to those being considered as roomies. The title of the novel on which the film is based is SWF Seeks Same… Not good optics today. Considering how historical culture is now coming under fire from today’s, I’m reminded of one of the great literary quotes from J.P. Hartley’s novel, The Go-Between - “The past is a foreign country: They do things differently there.” Let’s be mindful of those differences and be grateful that our culture has seen fit to challenge and change the assumptions and ‘norms’ of the past for the better without, I hope, eliminating the understanding of the reality of said past and its very different context.

SWF (this time, to save me typing) starts with a title sequence featuring a pair of twins, little girls playing with make up in a hugely mirrored bathroom. We glimpse a real moon and a real ageing apartment block and join fashion software designer Alison ‘Allie’ Jones blissfully in bed and in love with boyfriend Sam. After finding out from a voicemail that he had recently been unfaithful to Allie with his own ex-wife, Allie calls off the relationship. Trying to get over the break up, she interviews different women to share her extraordinarily roomy apartment in a seemingly crumbling, old block with rent control. Space in New York is, for many non-millionaires trying to make it there, the Holy Grail. A vulnerable applicant named Hedra (aka Hedy) arrives, with a neediness coming off her like klaxons blaring. She shares a drenching from a broken tap with her potential room-mate which kickstarts a bond between the women. All seems to be going well until Sam returns declaring his undying love and Allie is all too swiftly persuaded to forgive him. How do you think this goes down with Hedy who has been hiding Sam’s letters and deleting his voice messages? Well, so as not to spoil anything, we’ll leave it there with the addition of just one word to cover the rest of the narrative; escalation.

SWF is a two-woman show with some fine support but it’s the mutating dynamic between Allie and Hedy that drives the story to some dark places. As Allie, Bridget Fonda (Jane’s niece) is the perfectly cast, intelligent beauty who’s heart is broken and who mistakenly tries to mend it with someone who wants to be not just like Allie but Allie herself. Hedra is an unfortunate name right off the bat, leading you to think of the Hydra, a mythical multi-headed beast (not that wide off target). Hedy is a softer name for a steel soul, one afflicted with what was known at the time as Borderline Personality Disorder. She’s played chillingly and all too believably by Jennifer Jason Leigh. I recognised the character and her singular needs from personal experience interacting with people in my own life. I would like to state for the record that none went as far as Hedy does looking to quell her inner demons. After a tragic childhood losing her twin, Hedy is looking to shore up her fragile grip on her own identity by stealing someone else’s, someone she keenly fixates on. Leigh’s pout, the lip biting and the downward cast body language channels her rage and resentment vividly on screen and when the tables turn in her favour, she sloughs off that inward timidity and victim status and becomes a scheming force thinking that her overall plan will work all wrapped up with neatly tied bows ending with her leaving town in the clear. Early on, Hedy gets a puppy, very much like the dog she had as a child that she christens Buddy. Pets are not allowed in the apartment building. Buddy steers well clear of Hedy when he can. When at a low ebb, Hedy calls for the puppy but Buddy just yaps at the door after the departure of Allie and Sam. Hedy’s nails sink into her leg with frustration. While pigging out on the ultimate comfort food, a tub of ice cream, she gets her own spiteful back on Buddy by kicking it offscreen. Let me just soften that. It’s scooped aside with her foot so technically, the dog was not kicked. Nothing like mistreating an animal to confer ‘bad person’ status.

There are three supporting characters with just the non-threatening gay friend living in a flat above Allie’s being unfailingly warm and wise. Allie’s beau doesn’t behave well though we do have sympathy for him and the way he’s subsequently manipulated. The monster of the three attempts to force Allie into servicing him (not a great euphemism, granted) but ‘blow job’ is an ugly term, even if it’s sex worker short for ‘below job’. I have to say that each actor is utterly convincing in their roles. Playing the gay, unemployed actor Graham is Peter Friedman. He’s a good friend and gives good advice but he finds himself on the wrong side of Hedy. Allie’s boyfriend Sam is played by Steven Weber. Handsome and loving perhaps but Sam lets his desires get the better of him by having sex with his ex-wife while with Allie which gets the narrative ball rolling. It didn’t take me long to remember where I’d been impressed with Weber before. He played a TV network boss in Aaron Sorkin’s Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip. Set up to be the ‘asshole’ boss, throughout the series, Weber (with significant assistance from Sorkin’s scripts) humanises the man, allowing him to become a real character and not just a powerful bad guy. He made quite the impression. The monster of the three is Allie’s new boss Mitch, played by Stephen Tobolowsky. Tobolowsky is an actor that also makes an impression. As a jobbing supporting player, he’s made over 200 movies but I don’t remember him playing someone this odious. You’ll recognise ‘Ned’ from Groundhog Day I’m sure and I also remember him being awkwardly dated to get him to say the word ‘password’ so that Robert Redford’s team can complete their mission in the under-rated Sneakers. In SWF, he first plays unlikeable to the hilt in negotiating how much he’s going to pay Allie to use her new software which digitally changes clothes and colours on screen for his fashion business. Remember, this was the early 90s and colour screens for computers were on the way but not there yet. He writes down his clearly lower figure and when Allie begins a negotiation he cuts her off saying that was his final offer. We really are not keen on Mitch. And when he forces himself on her, any decent men watching would throw up their hands and utter “What is wrong with you?” and cheering a well-aimed double punch in the balls. The older I get, the more I’m convinced that our primal urges have a little more control over us than I’d care to admit. And finally, it’s always lovely to see Ken Tobey on screen as a hotel desk clerk. A favourite of director Joe Dante, Tobey will forever be one of the guys fighting The Thing From Another World, the original from 1951.

It’s clear from the nuanced and intelligent performances that Schroeder is an actors’ director. Right down to the style of editing (by Lee Percy), the actors, crucially, are given time. Straight after the assault by Mitch, we have a low angle mid-shot of Allie in deep shock. In today’s cinema these emotional bridges are often excluded in favour of pace. I’m flummoxed that ‘accelerated storytelling’ (to use once Doctor Who show runner Steven Moffat’s term) sometimes trumps emotional connection. SWF, if nothing else, is a character study of a disturbed mind versus a befuddled and vulnerable one. Part of how well magical moments play out has to be the result of rehearsal time Schroeder had with his cast actually on the real sets. Schroeder’s no slouch with the camera either. His camera moves intriguingly in the very opening bathroom sequence. It’s a single shot and ends with the camera taking the role of the mirror. He also has no embarrassment or excuses for this psychological thriller suddenly lurching into slasher genre territory in the last act. There is an inevitability to this. Again, the word escalation seems to cover that. There is frequent nudity in the film which attests to an evident trust the actors must have had in their director. Never salacious or gratuitous, the nudity is more grounded in character.

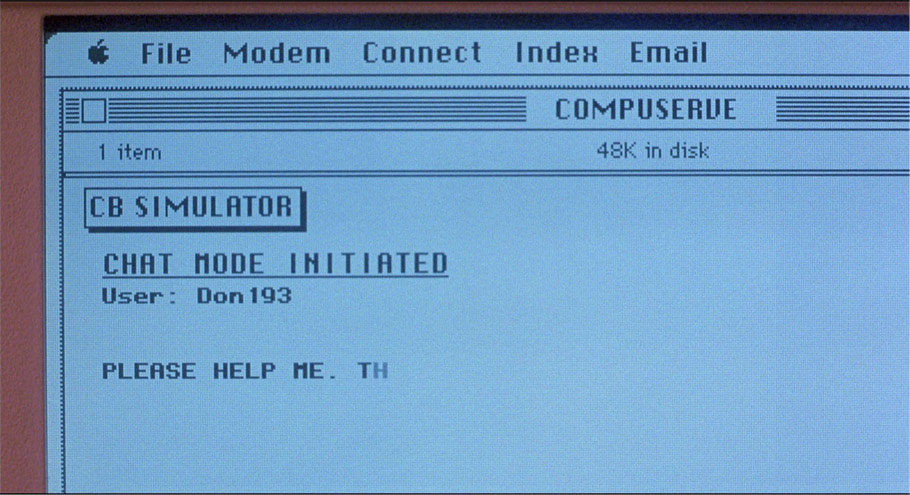

There are many other moments to enjoy. God, seeing the old Mac OS at work and does anyone even remember Compuserve nowadays? Milena Canonero’s career as a hugely successful costume designer is partnered with duties as a production designer on SWF. One of the playful details is featured in a close up of the grill that enables voices to carry at 9’ 47”. Next to it is a small night light with a design of a little girl using a powder puff, a nod back to the very first scene. I adore detail like this. Set decorator, Anne H. Ahrens, may have been responsible for this under Canonero’s direction. I also appreciated the ambiguity in the death of the puppy (sorry dog lovers but Barbet’s not your go-to guy if you want to avoid canine death). Did Hedy throw him out of the window or was it an accident because Sam hadn’t fixed the ornate railings? When Hedy gets violent, she immediately forfeits the right of immunity from consequence. But her first overtly violent act is against a character that our main ones do not interact with often which buys her enough time to finish her business. But when she takes Allie to the hairdressers and reveals herself as Allie’s double, this is when Allie’s caring for her strange new friend should cease and action should be taken to distance herself from her would-be doppelgänger. Looking as much as Leigh could look like Fonda, Hedy says to herself in one of what seems like several thousand mirrors in this film, “I love myself like this…” Another Hedy line which stuck in the mind was spat as an accusation at Allie. “I never met anyone so scared of being a woman.” That’s a profound line that has very little basis seemingly derived from Allie’s behaviour. It might have struck screenwriter Don Roos as a good put down but it doesn’t stand up to much scrutiny. That said, Roos’ adaptation is first class with the writing rarely calling attention to itself. The spooky, atmospheric building standing in for Allie’s apartment block is the famous Ansonia building in New York’s Upper West Side, almost as famous as those luminaries who’ve lived there..

As thrillers go, Single White Female is a classy and effective example of its kind. Driven by two superb central performances and a passionate and intelligent, detail-oriented director, it’s taut, fat-free and sometimes surprisingly chilling.

Ah, the 90s. Director Barbet Schroeder was at the forefront of the digital revolution shooting on high definition video but not until 2000, in parallel with George Lucas taking on the second of the Star Wars prequels sans film. But in the early 90s, it was celluloid all the way and the film looks lovely with no apparent scratches or dirt visible. It has an artistic softness to the close ups which is the hallmark of celluloid aided immeasurably by the lighting design. The use of shadow and light in the apartment studio set is particularly striking all lit with (inevitably) mirrors. Take a well-earned bow, Luciano Tovoli. The image is framed in the original aspect ratio of 1.85:1.

The DTS Stereo audio track has no evident issues of hiss or intelligibility. The mix is quite subtle with Howard Shore’s very effective score underlining threat but having no bluster of its own. This is how good composers serve the film and not their own music.

There are new and improved English subtitles for the deaf and hard of hearing.

It may be obvious to everyone but each of these extra features contains many spoilers. So enjoy the film first. Thank you.

Audio commentary with director Barbet Schroeder, editor Lee Percy, and associate producer Susan Hoffman (2018)

The instant first take away of this lively affair is that director, editor and producer are still very amiable together and this comes out time and time again as the three sometimes playfully mock each other. Schroeder reveals a lot of the detail in the interiors is based on that of his friends’ houses and apartments. They chat about how much signposting is too much, a question that continues to befuddle directors to this day. It all boils down to rewarding those who are paying attention. It’s curious to learn that much older known stars were considered by the studio but Schroeder stood his ground. The delicacy of the roommate relationship would have been skewed with older characters. I rather liked hearing that Whoopie Goldberg wanted a shot at one of the roles, presumably to mock the title? It’s nice to know that the director regrets the ‘white’ in the title but at that time there was too much money and effort put into the project to lose the title. At least it was shortened from the novel’s full title of SWF Seeks Same. The team praises the bravery of actors showing all in the service of their craft. Apparently Leigh wasn’t fond of a well-earned title of ‘One Take Jennifer’. This observation brought to mind the immense amount of time it took Rick Baker to design, devise and build the extraordinary prosthetics for An American Werewolf in London. When the animatronics performed superbly on first takes, Bottin felt frustrated (happily, I suspect) that they couldn’t have spent more time shooting them given how much effort went in to their creation. I suspect some actors like to dig in the dirt for the truths to be mined, and some just show up, nail it and move on. The only thing I could glean after some significant research was that the ending was not satisfying to a test audience and was reshot. Hunting for original scripts online is a hit and miss affair. I certainly couldn’t find the script as originally shot. There’s a happy ending to this frustration. Please see the next extra for details. Surprisingly, studio chiefs at the time were not keen on redheads. Such an odd thing to revolt against while snagging a director. This is a great extra stuffed with detail and all of it entertaining.

New York Interview: Barbet Schroeder (2018): the director discusses the production and release of Single White Female (27’ 20”)

With some inevitable repetition, director Schroeder takes us through the stories behind the making of the film. Unsurprisingly the violence and gore had to be toned down after test screenings. Schroeder reveals his principal favourite and influential directors were Nicholas Ray, Alfred Hitchcock and John Ford, all pretty solid choices. Hoping to get an insight into the original ending here but alas, thwarted.

And then I hit paydirt on what will be one of the most useful research sites I’ve ever visited and I know I must be so late to this particular party. All hail, the Internet Archive. So spoilers ahead. Skip this paragraph if you still haven’t seen the film. Ready? OK. The end of the book features a fight in the elevator between fleeing Hedra and chasing Allie. Allie smashes Hedra’s head into the wall and she slumps down. As the elevator reaches the lobby, detectives take her away. Not the most cinematic of endings. In the first draft of the screenplay, writer Don Roos has the fight starting but Hedra gets the upper hand and starts to strangle Allie. Foreshadowed earlier in the film, hanging on some string is a screwdriver used to close the metal lattice elevator gate. Allie snatches at it, rips it off its string and plunges it into Hedra’s neck, blood everywhere. Hedra almost smiles as she slumps forward. Allie leaves the elevator and gets some help from a neighbour… sirens blare outside. Well, the test screening audience weren’t having any of that malarkey. So a completely new ending was shot in which the inevitable happens but it takes its time, cat and mouse in the bowels of the building. There. Curiosity sated.

Upstairs with Graham Knox (2018): actor Peter Friedman recalls his casting and relates some anecdotes from the set (7’17")

The guy playing the guy with the cat in the flat upstairs has a cat allergy. Of course he has! Friedman tells us a little about his early career and confirms the reshoots and his role in them. He was required to bang the head of the stuntwoman doubling for Leigh on the floor. Apparently stunt people always groan when an actor performs their own stunts… someone’s getting hurt. Friedman called Barbet “the do-it-yourself guy,” something he respected and responded to.

The Fiancé Sam Rawson (2018): in-depth interview with actor Steven Weber (19’ 41”)

Weber is all too aware of an actor’s insecurities and announces that he thought Schroeder liked him straight off the bat. It was a surprise to find out he’d been directed by Dario Argento from Weber’s own TV adaptation of a horror comic book story, Jenifer. He essentially admits to playing himself in SWF and is thankful that now being older he doesn’t have to take his shirt off anymore! He also shares how difficult intimacy can be to shoot particularly a scene in the film where he inadvertently is unfaithful to his lover. Yes, you read that right.

WF Seeks Writer (2018): screenwriter Don Roos looks back on his adaptation of John Lutz’s novel and working with Schroeder (25’ 51”)

Roos was very familiar with the TV crime format (where you need your hooks and timing of big moments to stop the audience from turning over). His pitch to the studio at the time was seen as radical… Get this for radical… All the straight men are bad, the gay guy is good, and the hero and villain were both female. I think radical for 1992 is now de rigueur. There are sections of his original script intercut with his interview and if you’re paying attention, you can read the original ending so this would count as a spoiler but for a scene that was replaced. Roos then muses on the idea that young audiences today are so easily offended so that challenging human dramas have no commercial viability. He mourns that movies made about people are over on the big screen and that this kind of human drama is now only available on TV. He certainly has a point.

She’ll Follow You Anywhere (2024): the critic, broadcaster, and author of Unlikeable Female Characters Anna Bogutskaya dissects and contextualises the film within the context of the erotic thriller (27’ 20”)

Bogutskaya is clearly well immersed in her particular field. She sees SWF as coming at the tail end of the ‘erotic thriller’ genre and also notes historically this was the VHS era currently booming together with the rise of cable TV. The ridiculous slew of straight-to-video titles aping the successful cinema releases (Fatal Attraction, Basic Instinct etc.) I remember being very amused by. They promise sex and death. There’s your basic erotic thriller title. Don’t be surprised if you find Woody Allen at the end of that search… Bogutskaya also notes how the visceral reactions to these deranged females is almost primal in its own aggression. Test audiences tend to be a bloodthirsty bunch and all but ordered the filmmakers to dish out retributive justice or as the audiences say “Kill the bitch!” Lovely. Her examination of the themes and layers of the film are very insightful and you’ll learn a lot about the historical and cultural precedents for the characters. It goes some way to convince me that there’s a reason twins and doppelgängers are seen as evil. This is a great extra but it has many more spoilers than any of the others so beware.

Original theatrical trailer (2’ 03”)

This leaves you in no doubt which elements of the film were deemed to be commercial. The trailer plays on the psycho element and has shots from almost all the action which is really only the last 15 minutes. So it’s totally unrepresentative but totally Hollywood.

Image gallery: promotional and publicity material

These comprise of 2 black and white behind the scenes shots, 2 colour publicity shots, 3 colour behind the scenes shots, 5 black and white lobby stills and 7 of colour all rounded off with a colour poster.

Limited edition exclusive book with a new essay by Georgia Humphreys, archival essays, a contemporary article on the making of the film, and full film credits

Humphreys’ insightful essay Moi, Même takes a deep dive into the levels of artistic and psychological interpretation of SWF while commenting on detail of the practical production. She describes the role of the Ansonia building with a poetic relish giving it even more substance as a very real character in the film. Her insights into both main characters enrich the understanding of their motivation and frailties. Making Single White Female is a collection of quotations from director and his two leading actresses sourced from many 1992 interviews promoting the film. There are some insights into how Fonda and Leigh approached their roles which have not been voiced in any other of the extras. Critical Response features 10 reviews and articles, 2 sourced from the UK, the rest, the US. The broad stroke of each review is that it is judged to be a nuanced character drama becoming more suspenseful as the relationship cracks and then lurches into slasher territory. Not sure I agree with that assessment but it is a common response.

Beware the lower image on page 32. It shows (if you are looking for it) the climax of the original script as shot, outlined in my spoiler paragraph earlier and subsequently not in the film at all. It’s proof, if proof be needed, that there was a reshoot.

An intimate, chilling character study about real human beings is topped off with shocks and desperate violence which many contemporary reviewers found jarring. But since when were genres supposed to be rigidly adhered to? The threat of violence is threaded throughout this superior thriller and the narrative needed its sisterly catharsis. Single White Female was a film I liked at the cinema but it’s one I loved on Blu-ray. A great disc with terrific extras. Bravo.

* https://filmtalk.org/2018/11/15/barbet-schroeder-what-actors-give-in-a-scene-is-like-the-birth-of-life-the-most-important-magical-moment/

|