|

This is the third collection of short films which the British Film Institute have released on Blu-ray as part of their Flipside line. The first collection, which came out in November 2020 as Flipside number 41, was before my time on this site, but I reviewed the second volume (Flipside 43, released October 2021) here. Now, two years on, is a third volume.

Volume 1 contained nine films and Volume 2 ten, and another ten are present here. They form the usual miscellany of cinema releases, television productions (including one cinema/TV hybrid), public information films and non-theatrical pieces. Some are very short: those two public information films are under a minute each, and two television productions both come in around the three-and-a-half minute mark. At the other end of the scale, two films in this set are just under the forty-five minutes which the Internet Movie Database defines as feature-length.

On with the show!

Return to Glennascaul was written and directed in 1950 by Hilton Edwards. Edwards had been the co-founder of Dublin’s Gate Theatre, along with Michaél MacLiammóir. Back in 1931 a young man named Orson Welles had made his stage debut at the Gate. Now, they were working on Welles’s film Othello, with Edwards as Brabantio and MacLiammóir as Iago. During one of the many pauses in that film, the two men asked Welles to help out with this short film.

Many ghost stories are not told directly but at one remove or more, so we have a narrative inside a narrative, allowing for elements of ambiguity to be introduced. Here, Welles, playing a version of himself, breaks the fourth wall, by introducing the film in voiceover as “a short story straight from the haunted land of Ireland”. Driving home from a day’s work on Othello, he picks up a hitchhiker, Sean Merriman (Michael Laurence, also in the Welles film, as Cassio). As they travel, Merriman tells Welles how once when he was driving home himself, he picked up two women, a mother and daughter (Shelah Richards, Helena Hughes) and gave them a lift home. He spends the evening there, and is attracted to the younger woman, Lucy. However, returning the next day, he finds something entirely different…

This was the only film written and directed by Edwards, whose directing experience otherwise was on the stage. However, it’s an effectively atmospheric film, helped by Georg Frischmann’s black and white camerawork, and works as what Welles describes a “tall tale” for telling after dark. Return to Glennascaul went on to a UK cinema release in 1952 and two years later was Oscar-nominated as Best Short Subject, Two-Reel. (The winner was the Disney short Bear Country.)

Like Return to Glennascaul, Strange Stories tells us its tales at one remove and has real-life people as our hosts, though this time neither story is supernatural. Valentine Dyall drives John Slater to a train station, and they tell each other a story. The first story, “The Strange Mr Bartleby” is a loose adaptation of Herman Melville’s novella Bartleby the Scrivener (the first screen version of it, in fact), and sets up two storylines. A young woman (Naomi Chance) asks Gillkie (Norman Shelley), a solicitor, to trace a man called Stephen Zwane. Meanwhile, Gillkie encounters a mysterious tramp called Bartleby (John Laurie). In the second story, “Strange Journey”, based on the story “Saloon Passenger” by E.W. Hornung, Charles Kellerton (Colin Tapley) steals from his employer and in an argument kills him. Assuming the man’s identity, Charles and his wife Marie (Helen Horton) board a ship to Tasmania. They are the only passengers, and so they spend much time with the Captain (Peter Bull). But soon Charles suspects the Captain is on to him…

These two twist-in-the-tale stories were made by a UK independent company, Vandyke Productions, and were part of a series of shorts intended for the US television market, in a half-hour slot with introductions and afterwords by Adolphe Menjou. The directors were two men at the start of what would be longer careers, John Guillermin and Don Chaffey. With the Slater/Dyall frame added, the two stories were released in UK as a supporting feature under the present title. The stories are capably told, with “Bartleby” being particularly atmospheric, and this would have been a satisfying curtain-raiser for whatever main feature you were sitting in the one-and-nines for.

STRANGE EXPERIENCES: GRANDPA’S PORTRAIT

STRANGE EXPERIENCES: OLD SILAS |

|

More television material, two episodes out of twenty-five made by Derick Williams Productions in 1956, and intended for five-minute slots on the fledgling ITV network. (They actually run 3:26 and 3:32 respectively, to allow for commercial breaks.) They also appeared to have been shown on US television. So, while not the shortest films in this set, they are indeed short and maybe sharp but also rather slight. Peter Williams narrates the two tales, which are largely made up of stock footage and one or two actors, involving a mysterious painting and a killer fearing his victim might take revenge from beyond the grave.

Shot in black and white 35mm, Maze was made by Bob (billed as Robert) Bentley at the Royal College of Art Film and Television School in 1969. Bentley in the interview included on this disc admits the film is confusing, at least on a first viewing, and he’s right. Maze is the operative word – the film centres on two unnamed men, an immigrant with a hotel dishwashing job (George Votsis), and an upper-class man (Paul Stubbs). There’s also a woman called Marilyn (Stephanie Cleverley) who is concerned that her beauty means that people think her superficial and that no one listens to her. For twelve minutes, the film documents their interactions with each other and others, and while it’s visually striking, what it adds up to is for the audience to work out.

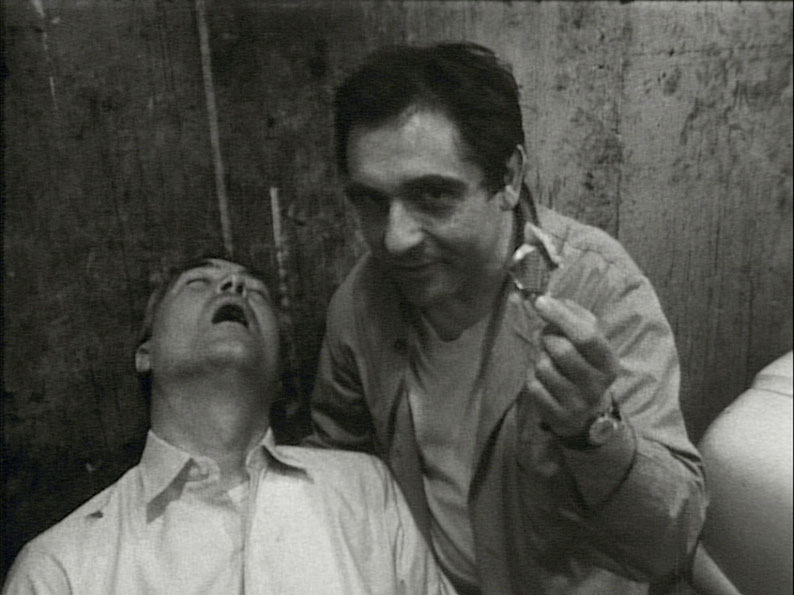

Three people – Wilf (Will Knightley), a teacher, Susie (Hilary Charlton), a nurse, and Henry (Henry Woolf), of no permanent job, decide to kidnap, torture and murder a government minister (Brendan Barry) as a revolutionary statement. They hire a blue-movie cameraman (hence the title), Georgie (William Hoyland) to film it all.

Skinflicker, written by Howard Brenton and directed by Tony Bicât, was one of the most controversial films ever made with BFI funding, and caused questions to be asked – apparently, once in Parliament – as to whether public money should have been used for this. (Before I go on, the title is often given as Skin Flicker – and it’s spelled that way on the copy of the script included in this Blu-ray’s extras – but it’s one word on screen.) Nowadays, it takes on further resonance, as a prototype found-footage film.

The huge success of The Blair Witch Project in 1999 was the wellspring for many found-footage films in the horror genre, examples of which are still being released today. However, as soon as Blair Witch hit the cinemas, people were looking back and pointing out earlier takes on the theme: Cannibal Holocaust (which is a mixture of conventional narrative and found-footage) and The Last Broadcast being popular examples. The 2021 documentary The Found Footage Phenomenon includes 1967’s David Holzman’s Diary (not horror but still pretty dark, and a film I admire greatly) and goes back to 1960 and Peeping Tom. Like Blair Witch, some people thought Holzman was real, a feeling only dispelled by the fact that the title and all the credits are at the end. The same could be said for Skinflicker and at a showing at a film festival in Rotterdam an audience member asked Bicât if he actually had kidnapped someone. The film mixes black and white 16mm footage (that shot by Georgie, or at least with his camera) and mute colour 8mm using a domestic camera owned by the kidnappers, and any technical imperfections are part of the aesthetic. The kidnapping is filmed using the latter, all silent except for crackle on the soundtrack. (Nowadays, of course, the film is technologically obsolete, as the three could have shot everything on a smartphone, with no need to hire anyone.) The footage is topped and tailed by captions and narration, presenting it all as a government training film – for authorised viewers only – for use in counter-subversive activity.

The cast are all professionals, with Henry Woolf standing out as the undoubtedly psychopathic Henry, an overgrown child demonstrating how far he can go, and you suspect liable to pull the wings off insects if you gave him the chance. It’s all very convincing, and intentionally disturbing.

Howard Brenton at the time was one of the leading up-and-coming younger (born 1942) British playwrights. Tony Bicât had known him via the Portable Theatre, which Bicât had founded with David Hare. Hare and Brenton would collaborate more than once, with their epic play Brassneck premiering in the same year (1973) that Skinflicker was released. Brenton would not escape controversy, later in his career, with his National Theatre play The Romans in Britain resulting in a private prosecution brought about by Mary Whitehouse due to a scene of on-stage male rape. He continues to write to this day, with his television work including a Play for Today and fourteen episodes of Spooks. He wrote Skinflicker as a potential television play, but Bicât persuaded him to make it as a film as no broadcast company then would touch a story like this, quite understandably. And so it was, becoming Bicât’s film directing debut.

Skinflicker went on to festival screenings and a limited cinema release, given that it’s an odd length (43 minutes, so a short by most definitions) and was distributed as it was mostly shot, in 16mm. It played as a support feature and in a wildly contrasting double bill at the Academy Cinema in Oxford Street, London, with Bill Douglas’s My Childhood. (They were both BFI-funded, are all or mostly in black and white and were all or mostly shot in 16mm and...well, that’s it.) Fifty years on, while inevitably a little dated, it retains its power.

BROKEN BOTTLE

DON’T FOOL AROUND WITH FIREWORKS |

|

Short and sharp indeed – no pun intended. It would no doubt take you longer to read this part of the review than it would to watch the twenty-nine and forty-two seconds (respectively) that it takes to watch these two wince-inducing films. Both in the long tradition of not being afraid to traumatise unsuspecting audiences in order to get their message across, both are models of economy. Both were made by the Central Office of Information in 1973, though information appears to be lacking as to who actually made them and who appears in them – just a young boy in swimming trunks running joyously along a beach in the first of these, a group of teenagers in the second. But they certainly work, and you’ll think twice before running along a beach in bare feet or chucking fireworks around, won’t you? Won’t you?

Paul Mallory (John Francis) is looking into Invex, a large corporation, when he dies suddenly. His colleague, Raymond James (Jack Galloway) and his wife Carol (Stacey Tendeter) investigate, which involves Raymond playing a mysterious computer game...

The Terminal Game was made in 1982, though conceived five years earlier, as a graduation film by writer/producer/director/editor Geoff Lowe from the National Film School. It was shot in 16mm. The actors were professionals, with Jack Galloway at the time a television star due to his title role in the Andrea Newman serial Mackenzie. Stacey Tendeter had played the latter title role in François Truffaut’s Anne and Muriel. Score composer Colin Towns appeared elsewhere in the BFI Flipside series with Full Circle (aka The Haunting of Julia). While it’s not technically science fiction, The Terminal Game is heavily dominated by then-current computer technology, and it was a few years too early to catch the wave of what would become cyberpunk. It’s not always easy to follow, but it’s an intriguing piece up until its kind-of apocalyptic ending.

Of all the short films on these discs, Wings of Death is no doubt the one which most people will have seen in the cinema, as it accompanied A Nightmare on Elm Street on its 1985 UK release. As with many of these combinations, it’s pot luck as to what the audience for the main film would have made of it as they would have watched it most likely knowing nothing about what they would see in the next twenty-one minutes. No doubt many found it more than a little “arty”.

Wings of Death is a semi-surreal look inside the head (sometimes literally) of a young heroin addict, Alex (Dexter Fletcher), inside a seedy London boarding house, with hallucinatory and at times distinctly disturbing results. Written and directed by Nichola Bruce and Michael Coulson, it’s the most recent film in this set. Gale Tattersall’s 35mm cinematography is very colourful and vivid, though it’s unfair to compare it to the look of films later in the decade which now look very overlit so they didn’t devolve into murk when watched on VHS, their most likely output. The cast features two up-and-coming youngsters, who had begun his career as a child as far back as 1973 (the year he turned seven). It was Wings of Death which brought him to the attention of Derek Jarman, who cast him as the title role of Caravaggio. Fletcher would continue to act as an adult, and has since become a director. Kate Hardie, two years younger, had begun her own career in as a teenager and has IMDB credits as far as 2019. Here she plays Alex’s girlfriend Looey and is affecting despite not much screen time and minimal dialogue.

Short Sharp Shocks Volume 3 (Flipside number 47) is a two-disc Blu-ray release from the BFI, five films on each disc. The discs are encoded for Region B only. The set has a 15 certificate, which is due to Skinflicker (originally bearing an X certificate for cinema release) and Wings of Death (a 15 in the cinema and retaining that certificate now). Return to Glennascaul was a U originally, but is now a PG. The same applies to Strange Stories, whose cinema certification is under the title Two Strange Stories on the BBFC website, though the film doesn’t appear ever to have been released as that. The remaining films are certified for the first time: Grandpa’s Portrait at U, Old Silas at PG, Maze and The Terminal Game both PG. The two public information films appear to have been exempted from certification.

The films were originated in a variety of formats – black and white 35mm for everything on Disc One. Skinflicker was black and white 16mm with some sequences shot in colour on 8mm. The Terminal Man was 16mm colour and the two public information films and Wings of Death, 35mm colour. The transfers come from a variety of restorations and scans. Return to Glennascaul is from a 2K scan from an original finegrain duplicating positive and is a little soft, with shadow detail disappearing a little in the darker scenes. The two Strange Experiences shorts are also scanned from finegrain duplicating positives, and are also a little dark, and are certainly grainier, particularly the stock footage. Strange Stories is based on a 2K scan from the original negative, and this being at least one generation earlier shows the difference – it’s sharp with strong blacks and good greyscale, with natural-looking grain. Maze was scanned in 4K from Bob Bentley’s own 35mm negative. There’s quite a bit of grain, but not displeasing, but there is also some damage, light scratches down the left hand side.

On to Disc Two. Skinflicker comes from a standard-definition source and is therefore an upscale. The film was shot in both 16mm black and white and 8mm colour, and given its premise is entirely intended to be lo-fi. That’s certainly the case: while contrast is fine, the film is pretty grainy and is very soft and grainy in the 8mm sequences. The two public information films are scanned from 35mm interpositives. Broken Bottle looks quite washed out, likely faded, but the colours are stronger on Don’t Fool Around with Fireworks. The Terminal Game comes from a 16mm positive, and its origins are obvious, being quite soft and grainy and quite contrasty, often the case with films mastered from positive elements. There’s a big jump with Wings of Death, a 2K scan from the 35mm negative. The film is a very bright and colourful one, and that comes over well in this transfer, which solid blacks and natural grain.

The aspect ratio is 1.37:1 in all cases. That’s undoubtedly correct for Return to Glennascaul and Strange Stories, made before cinema went widescreen (only just before, in the latter case) and in the case of the latter, most of it was made for television, which then was 1.33:1. Television was the medium for the two Strange Experiences shorts, and Maze was not intended for theatrical exhibition – Bob Bentley’s input into this release would lead you to suspect that the ratio is correct for his film. Skinflicker and The Terminal Game were shown non-theatrically in 16mm, so 4:3 is correct for those, as it is for the two public information films, which would have been shown mainly on television and in any case also non-theatrically. The one I’d query is Wings of Death, as that was a 35mm film given a cinema release at a time when commercial screens (other than arthouses and repertory venues) could not show Academy Ratio, and it would have been shown there in a wider ratio, in UK cinemas at the time quite likely 1.75:1. There is sufficient headroom in every shot to indicate that the film was framed for a wider ratio.

The soundtracks are LPCM 2.0 in all cases. That means mono for everything except The Terminal Game, which has a stereo (left, right and centre only) track and Wings of Death. The latter doesn’t have a Dolby Stereo credit at a time when films were still being released in mono in cinemas, including the film it supported, with many screens not yet Dolby-enabled. The track on this Blu-ray does have surround, though mostly ambience. Generally the results are clear and well balanced, with crackle on Skinflicker being no doubt intentional. There’s some hiss on The Terminal Game, which may reflect the element (a positive) it was mastered from.

Subtitles are available for the hard of hearing for all the films, but not the extras. I spotted a couple of errors, with “retches” being misspelled as “wretches” in both Skinflicker and Wings of Death. (Emetophobes be reassured that we don’t see anything happen onscreen.)

A Vandyke Production (6:46)

A look by Vic Pratt at the small company which made Strange Stories. Vandyke was set up and run by brothers Roger and Nigel Proudlock, and as well as the present short, they made other small-budget features in the 1950s. Pratt tells the story with the aid of a scrapbook provided by Roger’s son Nick, and it’s a fascinating look at one of the less-heralded byways of British cinema of the time.

Getting Lost (19:37)

Bob Bentley talks about Maze. He begins by talking about his time at art school, and a project called 1+1+1+1 (which may of course not be spelled that way), where four people made four short films and appeared in each other’s. He does give an explanation of Maze, which is fair enough as the film could do with one. Some scenes came to him in dreams. Maze did however, attract the attention of Bruce Beresford, then the Head of Production at the BFI, who invited him to submit an idea, which became the 1970 short Having a Lovely Time, which has a connection with another film in the set, see below. (Neither Maze nor Having a Lovely Time have IMDB entries as I write this. Maybe the latter will turn up in a future release.)

Maze image gallery (2:56)

A self-navigating gallery of black and white stills taken by Bentley during the production of Maze. And that’s it for Disc One.

Touch a Nerve (25:59)

Tony Bicât is interviewed about Skinflicker, which he begins by talking about his life and career up to that point. He received BFI funding for the film at a time when very different filmmakers like Bill Douglas and Kevin Brownlow and Andrew Mollo were also in receipt of it, and the film was made for £3000 after the BBC unsurprisingly turned the script down. Bicât had known most of the cast personally, but Brendan Barry and Henry Woolf had been new to him, and the latter at first passed on the project. Because of the mixture of colour and black and white, and the different original gauges, the film was printed all on colour (16mm stock). Bicât talks about the controversy surrounding the film, with someone at the BFI allegedly urging the film to be destroyed, and he praises Mamoun Hassan and Denis Forman at the Institute for their support. While Bicât has continued a career, he says that Skinflicker was very much not a calling card.

Skinflicker image galleries

There are three. Firstly, there is a copy of the sixty-five-page script, with pencil annotations by Henry Woolf. Secondly, a set of stills from the production (8:56) and finally an ephemera gallery (2:08). This begins with the letter from the BFI Production Board and a synopsis for the film and includes such items as the fascinating programme for the New Cinema Club in 1973, which includes not just Skinflicker, Bob Bentley’s Having a Lovely Time and also David Cronenberg’s early short feature Crimes of the Future. Other festival programme listings are included, as are some press cuttings from the UK cinema release, including ones from six newspapers and Time Out, and Alexander Walker’s piece in the Evening Standard asking how such a film could be made with taxpayers’ money.

A Game of Two Halves (27:55)

Geoff Lowe takes the stage to talk about The Terminal Game, beginning with his time at film school. His first ambition was to be a writer, and sent spec scripts in to the BBC, one of which was taken for the Second City Firsts strand. His short film was, familiarly enough, inspired by such dystopian novels as Nineteen Eighty-Four and Brave New World, and had some pushback as “no one wants to watch a film about a computer”. Not at all surprisingly, Lowe is well up on technology, and has been making use of AI as part of his writing process.

Playing Music (8:21)

Colin Towns talks about his music score for The Terminal Game, an interview presumably shot at the same time as his interview on the BFI’s Full Circle disc. He talks about his use of synthesisers, much in evidence in The Terminal Game, and his rather wayward career.

The Terminal Game trailer (2:37)

It’s something of a surprise that there is one, given that The Terminal Game is a short film not before now given commercial distribution, but here it is.

Flying High (31:22)

Co-writers and co-directors Nichola Bruce and Michael Coulson talk about Wings of Death. They met at art college and were in a relationship for a while, but continued to work together even after that relationship ended. Coulson made what sounds like a prototype video for the title track of Wings’s album Band on the Run, which he sent to Paul McCartney. He heard nothing more until years later when the film ended up on a DVD included in an anniversary edition of the album. (I hope he was suitably recompensed.) After art college, the pair worked on storyboards and poster designs for British films of the time such as The Company of Wolves. Wings of Death displays several influences, William Burroughs among them, and was filmed in a then particularly grotty part of London. Working as a team had its side effects, with many of the questions on set going to Coulson, with Bruce being asked about things such as makeup, despite Coulson being more expert in the subject. They praise Dexter Fletcher for his commitment to the role, which included having his head set on fire. Fletcher and Hardie played a couple in a relationship very professionally, given that they’d recently ended a real-life relationship of their own. The film was shot silently, with sound added later. They talk about the premiere at Cannes, and a television showing on Channel 4, as well as the cinema release.

Wings of Death: Behind the Scenes (6:59)

Nichola Bruce’s 8mm behind-the-scenes footage of the Wings of Death shoot, presented chronologically and mute.

Wings of Death image galleries

Two of these, the first being a series of black and white stills shot by Steve Pyke (3:50) and the second being an ephemera gallery mostly made up of the co-directors colour paintings, used to advise the cinematographer and production designer of the look they were after.

Booklet

Available with the first pressing of this release, the BFI’s booklet runs to thirty-two pages plus covers. It begins with a warning of potential spoilers and an introduction by this set’s three curators (Vic Pratt, William Fowler and Josephine Botting). As this is the third Short Sharp Shocks set, there’s not much to say that hasn’t been said before, so they keep it short, two paragraphs.

The booklet then proceeds disc by disc and film by film, with some quite extensive notes. Jonathan Rigby gives a detailed look at Return to Glennascaul, likewise Botting on Strange Stories, and – rather shorter on shorter films – Vic Pratt on the two Strange Experiences pieces. Directors both alive and able to participate contribute to the booklet as well, so we have Bob Bentley on Maze, though much he says here overlaps with his interview on the disc.

On to Disc Two, and likewise Tony Bicât on Skinflicker, and this actually expands on his disc interview. Mamoun Hassan gave him the (assistant) producing job on the sequel to his double-bill partner, Bill Douglas’s My Ain Folk, and he became a writer-director with Dinosaur (1975), also BFI-backed. As for Skinflicker’s controversy, it was almost matched by his 1991 Screen Two production The Laughter of God, which was almost banned before being cleared for its one and so far only broadcast. This is followed by a piece on Skinflicker by Sarah Appleton, who shot and edited the interviews on the discs. She’s here presumably in her capacity as co-director of the documentary The Found Footage Phenomenon referred to above, and her piece looks at Bicât’s film in the terms of the subgenre.

The booklet then goes out of disc order with pieces by both directors on Wings of Death, which again overlap somewhat with their disc interview. Vic Pratt talks about the two public information films. Finally, there’s Geoff Lowe on The Terminal Game and artist/filmmaker George Parfitt also contributes his view of the film. The booklet concludes with notes on and credits for the special features and details of the transfers of each film, plus plenty of stills.

After three releases, there’s plenty of life left in the BFI’s Short Sharp Shocks series, and I doubt there’s anyone outside the BFI to whom none of these sets is new. No doubt many of those reading this will have wishlists of films they’d like to see included in future editions, and rights and licences permitting, let’s hope we may get to see them.

|