|

Short films have been around since cinema began; in fact the first films made were shorts, and it was eleven years from the Lumière Brothers’ first programme of projected films that a feature-length film was made. (That was The Story of the Kelly Gang, made in 1906 in Australia. Originally around an hour long, about twenty minutes of fragments still exist.) For the purposes of this review and, I sense, the set under review, a feature is a film of an hour or more. Other definitions do exist, such as the Internet Movie Database’s forty-five minutes plus, and lengths in that length range have been distributed as main features: for example, last year’s shot-in-lockdown Host, all of fifty-seven minutes. But even when feature films were established as the main form of cinematic entertainment or otherwise, there was still room for shorts as part of a supporting programme which also included cartoons and newsreels and sometimes a second, often shortish, feature. All that had been reduced by the time I was becoming a regular cinemagoer in the 1970s. Nowadays, short films have become rarer in commercial distribution, though Disney and Pixar have kept up the tradition of providing curtain-raisers to their animated features. Needless to say, many short films were dire (I give you British Hustle, forty-four minutes of people dancing in a disco, and as exciting as that sounds) but others made an indelible impact. I can still remember short films that I saw in the cinema way back when, not knowing anything about them other than the title and BBFC certificate in advance. In some cases, I now forget what film I saw the short with, the film which was after all what I’d paid my money to see. One of those shorts is included in this set.

Creatively if maybe not commercially, the short film is as valid as, and distinct from, the longer form, and that’s true in visual media as it is in the written word. Short films can be made in any genre (fiction or documentary) but horror particularly lends itself to the shorter length. Think how many classics of the written genre are actually short fiction, up to and including novellas, than novels. Needless to say, there are plenty of short films available to be put together in a collection such as this. The first Short Sharp Shocks volume, released in November 2020 as number 41 in the BFI’s Flipside line, collected nine of them. Another ten are in the present Volume 2, taking us from 1943 to 1986. This selection is, like the first, offers a variety of styles and content, but are linked by a sense of the macabre, if not always actual horror. I’m sure we can all name films which we’d like to see included in further releases, though the issues will always be the availability of materials and the ability to license the films from their rightsholders, not always possible with certain major studios. But here are the ten films, presented on the discs and reviewed here in chronological order.

| QUIZ CRIME NO 1 / QUIZ CRIME NO 2 |

|

There were six Quiz Crimes in total, made between 1943 and 1945. The first one sets the theme. Detective Inspector Frost (Carol O’Connor) sits at his desk and talks to the audience, at one point admonishing the couple in the back row for not paying attention. (Best not to ask what they were doing.) In just under a quarter of an hour (one reel in old money), Frost takes us through “The Crooked Billet Murder” and “Back Stage Murder”, and asks us to spot the clues that allowed him to catch the culprits. The second Quiz Crime has a different host, another Detective Inspector (played by Max Earl), who does the same with “The Case of the Stolen Boy” and “The Hairless Boarder”. Once again, are you smarter than the DI and can you spot whodunnit? I didn’t, but no doubt many in the one-and-nines during wartime might have done. It’s a formula which has been pretty durable: in fact, it was the whole premise of the 1970s television game show Whodunnit?, hosted by Jon Pertwee during and after his stint as Doctor Who.

A creepily atmospheric three minutes from 1946. Two young boys and a girl go out to play, to run an errand. However, in the woods is a strange man. This film is not about the dangers of talking to strangers: who this man actually is, I’ll leave you to find out. Little is known about this film, written by one A.F. Bishop and made by BFU Limited (most likely the Blackheath Film Unit), one of several public information films they made at the time for showing in local cinemas.

Many short films act as proving grounds for those behind or in front of the camera, so you can find early work from people who would become much more famous later on. That can be disconcerting, with hindsight. Put it this way – would John Le Mesurier be your first choice to play a psychotic criminal on the run? That’s not a criticism of his range as an actor, but a reflection on the type of roles he is now best known for. Made in 1948, Escape from Broadmoor is the debut as writer and director of John Gilling, who signs his name in the opening credits and promises this to be the first of a series of psychic mysteries. While the film is fiction, it was inspired by recent escapes from the Criminal Lunatic Asylum (as it was then called) in the title. While Langford, real name Pendicost (Le Mesurier), has made his escape, the police investigate. Finally, Langford and his associate arrive at a house which Langford had broken into ten years earlier. But who is the young woman (Victoria Hopper) at the house, and why is she there? At 39 minutes, this does push at the limits of the short film. You may be able to guess the reveal, but it works once you get there, though the film takes too long getting there.

The first Short Sharp Shocks featured two short films (Death Was a Passenger and Portrait of a Matador) both made in 1958 by producer/director/co-writer Theodore Zichy (whose directing credit is simply Zichy, in an elaborate font with a star instead of the dot over the I). Mingoloo was the third short film he made that year. Zichy was a flamboyant character, a sometime actor (he’s in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp) and director of these three shorts and two features. Zichy also raced cars, flew planes and entered photography after the War. His three short films were made at Merton Studios, not the most lavishly-appointed of filmmaking venues, and Zichy’s films don’t always rise above their budgetary limitations and are sometimes best described as eccentric. Incidentally, Josephine Botting’s booklet notes state that while the original negative had existed in the archive for many years, until it was digitised it had not been possible to view it – and a viewing revealed that its title was Mingoloo and not Mingaloo, as had appeared in all the paperwork up to then. As for the film, it’s a slight story of the Chinese dog of the title, dreamed up by sculptor Mark Langtree (Anthony F. Page, the film’s co-writer and score composer), who immediately sets about making the dream a reality. This attracts the attention of foreign dignitary Leventa (Reed de Rouen) who plans to use the Mingoloo sculptures as aids to his sideline in drug-dealing. Langtree’s assistant Linda (Therese Burton, seemingly acting and enunciating as if she’s in a stage farce) is embroiled in the plot, which takes a few twists and turns in twenty minutes. Zichy’s films – the best to my mind being Death Was a Passenger – are singular to say the least, which may or may not be a good thing. After his two features in the early 1960s, Zichy and his wife became a cabaret act and future attempts to re-enter the film industry came to nothing. By then he had become Count Zichy, having inherited the title from his Hungarian aristocrat father. He died in 1987.

| JACK THE RIPPER WITH SCREAMING LORD SUTCH |

|

Contrary to what some people might think, the music video wasn’t an invention of the 1970s. This three-minuter from 1963 was made to be played on “Cinebox” machines in pubs and nightclubs – basically video jukeboxes, though with film loops rather than videos. Long before he founded the Monster Raving Loony Party and lost deposits he could afford to lose in election after election (thirty-nine of them, a record), Screaming Lord Sutch (David Edward Sutch to his parents) was a pop star, produced by Joe Meek, with a horror-themed stage show long before Alice Cooper had similar ideas. “Jack the Ripper” didn’t trouble the charts, though that may have had something to do with its being banned by the BBC for being tasteless, which it certainly is. But here in full colour and 35mm, you can watch Sutch gurning at the camera in his top hat and tails as he sings a jolly ditty about one of Britain’s and the world’s most famous serial killers.

Some combinations of feature and accompanying short work perfectly. Others do not, and you can imagine audiences squirming impatiently in their seats waiting for the main feature to start. That’s one value of a compilation like this set, as you’ve come for the short and not the feature, so any mismatches of tone or style or subject matter are less likely to happen. You wonder what those paying to see Death Weekend (tagline: “It started with a rape. It ended with a massacre!”) made of the supporting short The Face of Darkness. If they didn’t chime with it, they’d be sitting there for nearly an hour – this short is actually longer than some main features have been. The only writing/directing credit for Ian F.H. Lloyd, The Face of Darkness has been on people’s wishlists for some time, and here it is.

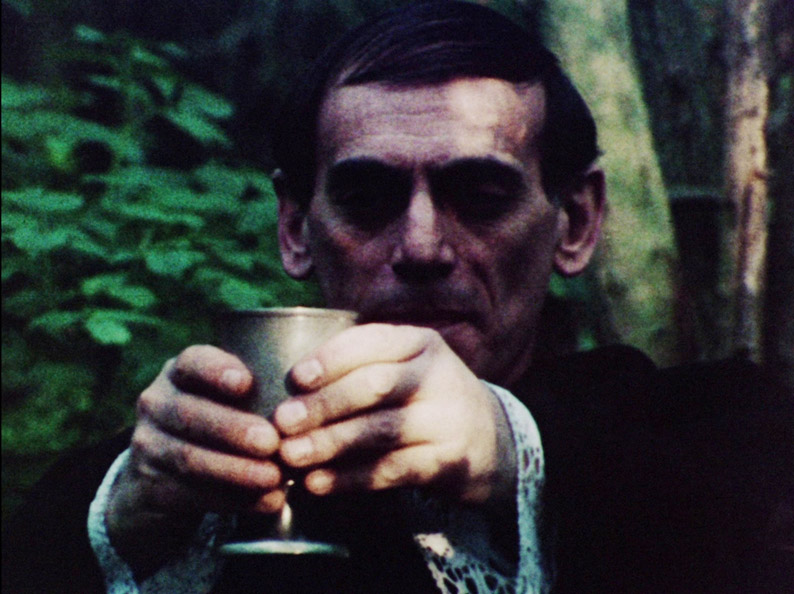

Edward Langdon, a right-wing Tory MP (Lennard Pearce), is behind a bill to introduce identity cards and to restore capital punishment for terrorist offences. He has a motive for this, given that his wife was murdered by an extremist group. To reach his goal, he uses ancient texts to revive a man who was excommunicated in the fifteenth century and buried alive, a man referred to as The Undead (David Allister). Langdon’s purpose is to engineer a violent outrage to enable his bill to pass on the back of public outrage, but Undead has other plans. The Face of Darkness, made on a tiny budget in 16mm, blown up to 35mm for its cinema release, suffers, as Lloyd freely admits in his interview on this disc, from a common problem in first (almost) features. It tries to fit in too much and doesn’t quite hit the horror-genre beats, for those simply wanting to watch a horror film, while slipping in its political and other angles, for those looking for them. Pearce is better known now as Grandad in the first three series of Only Fools and Horses (he died in 1984) and Gwyneth Powell for those of a certain age will be remembered as Mrs McCluskey, the longstanding head teacher of Grange Hill. She is still acting.

The Dumb Waiter accompanied the 1979 Dracula in British cinemas. I didn’t see it then, not being old enough for the (then) X-certificate main feature. I did however see The Dumb Waiter a few years later, accompanying I don’t remember which film (I’ll have to check through Universal’s releases of the time to see if any title clicks) at my local cinema. I can still remember that showing vividly nearly forty years later, especially the ending, and even then I noted the director’s name: Robert Bierman. The lead was played by Geraldine James, whom I did recognise from television roles. When the film was made, she had won acclaim for the 1977 TV play Dummy, directed by Franc Roddam, who had recommended James to Bierman, but her roles in The History Man, I Remember Nelson (as Lady Emma Hamilton) and especially The Jewel in the Crown were in the future. Needless to say, The Dumb Waiter has nothing to do with the Harold Pinter play of the same title.

A young woman (James – billed as “Girl” in the credits but her character’s name is Sally) is troubled by threatening phone calls from an unknown man (John White), who progresses from there to harassing her in her car and finally trying to break into her flat. The ending is hiding somewhat in plain sight (though I didn’t see it coming first time round) and the film ends ambiguously, which is one reason why it made an impression on me all that time ago. Undoubtedly the film caught the wind of the boom in slasher movies that followed in the wake of Friday the 13th (and which I wasn’t old enough to see at the time, though I was certainly aware of them) and it’s undeniable that this film does rely on the terrorisation of a woman on its own. In that way, it had resonances then which are still resonances now, post #MeToo.

Bierman begun his career making commercials, through which he had the services of a first-rate cinematographer, namely Billy Williams. He made a second short film in 1983, a version of D.H. Lawrence’s The Rocking Horse Winner (which isn’t mentioned at all in Bierman’s interview nor in the booklet and could be a candidate for a future release as it’s a horror story of sorts), which was nominated for the BAFTA for Best Short Film. After work in television, his best-known features are his version of the George Orwell novel Keep the Aspidistra Flying and especially the Nicolas Cage-starring Vampire’s Kiss.

This public information film is in similar vein to those collected on the BFI’s Best of COI release from last year. Intended to point out the dangers of building sites, but it isn’t aimed at unwary children wandering on to them but at the people who work there. Our host is a man in a black vest and mask. Spot the hazards which lead to repeated falls orchestrated by longstanding stuntman Stuart Fell, and eventually our host will complete his game of Hangman. Be aware!

The Mark of Lilith harks from a different tradition, where narrative in a conventional sense is put in the background and the film’s ideas are up front. Lilith, according to tradition, was Adam’s first wife and when she refused to have sex with him in the missionary position, she was replaced by the more compliant Eve and was both exiled and demonised. Zena (Pamela Lofton) is a researcher investigating the ways that the horror dramatises the other as threatening, and that other is often “the monstrous feminine”. Case in point, Lillia (Susan Franklyn), a vampire whom Zena meets and begins an affair with, and they discuss the links between female monsters and how society makes women other, particularly if they are of colour or gay or both. This is far more along the arthouse spectrum than the other films in this set, and like others of its type was mainly shown non-theatrically, in festivals and at co-operatives, distributed in 16mm (in which it was shot) and on VHS.

Short Sharp Shocks Volume 2 (Flipside number 43) is a two-disc Blu-ray release from the BFI, both discs encoded for Region B only. The first six films are on Disc One, with the remaining four and the extras on Disc Two.

The package has a 15 certificate, which is due to The Dumb Waiter, an AA originally. The Face of Darkness was also a AA at the time and would also be a 15 now, but a new certification doesn’t appear on the BBFC site at the time of writing. The Mark of Lilith was originally released non-theatrically without a certificate, and is also a likely 15. The two Quiz Crimes and Escape to Broadmoor were all A in cinemas at the time and are now PG. Mingoloo was a U. Jack the Ripper and Hangman were not released theatrrically so were not submitted to the BBFC at the time.

All the films are transferred to Blu-ray in a ratio of 1.37:1, except for The Dumb Waiter, which is in 1.66:1. That’s certainly correct for the first four films in the set, all of which predate the widescreen era. It’s also undoubtedly right for Jack the Ripper and Hangman, which weren’t made for theatrical distribution, and The Mark of Lilith, which was shot in 16mm and only distributed in that gauge and on VHS. It also looks right for The Face of Darkness, which was another 16mm (standard 16mm, not super 16mm) production: no doubt anyone who saw it in a cinema in its 35mm blowup would have watched it cropped, but it’s not the most precisely composed film to begin with. That leaves Mingoloo, which as a 35mm production from 1958 you’d certainly expect to be in widescreen, and the way the credits are framed and the fact that there is a lot of headroom in every shot which isn’t a close-up does strongly suggest that it’s intended for a wider ratio than Academy. As for The Dumb Waiter, there’s a copy of a call sheet in the image gallery and that indicates that the intended ratio is in fact 1.85:1.

Jack the Ripper with Screaming Lord Sutch

As for the transfers themselves, they are based on 2K scans from a variety of sources and the results depend on what is held in the BFI National Archive. The best-looking among the black and whites are the two Quiz Crimes, both scanned from finegrain duplicating positives, and Mingoloo, which is from the original negative. Slightly further away from the originals are The Three Children, from a duplicating negative, copied from a nitrate print, and Escape from Broadmoor, shot in 35mm but held in a 16mm print and somewhat soft as a result. On to the colour films: Jack the Ripper comes from a 35mm interpositive and looks fine, with strong colours, even when watching on devices larger than the Cineboxes it was intended for. Hangman was scanned from a 16mm print, and given its origins in that gauge, looks fine. The other three films were scanned from projection prints loaned by the directors or in the case of The Mark of Lilith the co-director Bruna Fionda, and the transfers are as a result rather darker and more contrasty than they might otherwise be. The Mark of Lilith and especially The Face of Darkness are intensely grainy, as befits their 16mm origins.

The soundtracks for all the films are the original mono, rendered as LPCM 1.0, and there’s nothing untoward, with dialogue, sound effects and music well balanced. English hard-of-hearing subtitles are available for all the films but not the extras.

Darkness Falls: Interview with Ian F.H. Lloyd (43:23)

Lloyd talks about his career, beginning as a documentary cameraman. He talks about his one and only fiction feature, proud of the fact that it was made and he could see its title on cinema billboards when it went on release. It was shot on a tiny budget with the cast and crew receiving the minimum salaries legally possible, with a promise to triple that if the film was distributed, which it eventually was. He’s open about the film’s flaws, mainly those of trying to cram too much into his first film, just in case he never got to make another, which he didn’t. He also acknowledges that the film doesn’t succeed in entertainment while conveying the ideas he wanted to get across. A genius might have been able to do that, but he wasn’t one.

Heads Will Roll: Interview with Robert Bierman (39:45)

Bierman turns out to be Lloyd’s rival in self-deprecation as he talks about his career, entering the film industry at a young age, by his own admission without a clue, before moving on to directing commercials and making his first short film (the one on this disc) in his late twenties. He does talk about how The Dumb Waiter was made, and its release, at first with Dracula and then with other Universal titles (including An Officer and a Gentleman, incongruously enough) before he took the rights back. Bierman also talks about his two cinema features, the cult item Vampire’s Kiss (featuring Nicolas Cage in unhinged mode) and the more comedic Keep the Aspidistra Flying, which opened the London Film Festival. As I say above, there’s no mention of his other short, the BAFTA-nominated The Rocking Horse Winner, which does lead me to speculate that that part of his interview is being held over to accompany a release of that film in another set or as a Blu-ray extra. We shall see.

The Mark of Lilith

Making Their Mark: Interview with Bruna Fionda, Polly Biswas Gladwin and Zachary Nataf (33:03)

The three directors of The Mark of Lilith assemble, the first two on a sofa in the house where some of the film was shot, while the New York-based Nataf joins in on a computer monitor. They talk about how they met at the London Film-Makers’ Co-operative and from there to film school. The Mark of Lilith began as a film school project, made with the school’s budget (£700 per student) and by pulling in favours, including from film equipment companies. They discuss the themes and the style of the film, with techniques originating with Brecht and in the cinema Godard to the forefront.

Puttin’ on the Ritzy (12:42)

An interview by video conference with Clare Binns, who talks about the Ritzy Cinema in Brixton (where one scene in The Mark of Lilith takes place) then and as it is now. She had her first job there at age nineteen in the early 1970s. Then it was a more political south of the River alternative to the Scala in King’s Cross, with a programme that changed daily, including some radical film and documentary, sometimes putting on women-only showings. There’s a scene in The Mark of Lilith where Lillia, clearly not finding anything at the local three-screen to her liking, asks the taxi driver to take her to the Ritzy. When the film was shown there, that line provoked a cheer. In fact, says Binns, taxi drivers and local residents often disapproved of some of the clientele as the cinema was very friendly to queer and otherwise alternative viewers. Nowadays, the Ritzy is a part of the Picturehouse cinema chain and shows a more conventional selection of films, but Binns is keen that while the cinema may show the likes of Free Guy, maybe curious audiences could come along to documentary screenings, often with Q&As.

Image Galleries

The Face of Darkness (3:30)

The Dumb Waiter (5:10)

The Mark of Lilith (12:20)

Self-navigating galleries, including production paperwork, advertising materials, stills, and in the case of the last-named, cuttings from Ritzy programme listings for when it was shown there.

Booklet

The BFI’s booklet, available with the first pressing only, runs to thirty-two pages plus the covers. It begins with an essay by this set’s curators (Vic Pratt, William Fowler, Josephine Botting) which starts by giving out various definitions of “short” as opposed to “feature-length”, as I do myself above. It does assume that the purchaser most likely bought the first set a year ago and read the essay in the booklet there (the former is a fair assumption, maybe not so much the latter) so it doesn’t repeat too much here. So, for example, there’s no mention of the Eady Levy and its abolition, which reduced the market for shorts pretty much straight away.

Each of the shorts receives notes from one of the three or other contributors. Jon Dear discusses the Quiz Crimes, Jonathan Rigby Escape from Broadmoor, while Botting writes about The Three Children and Mingoloo, Pratt about Jack the Ripper and Fowler about Hangman. The directors of the remaining three say their piece about their own films. In addition to Bierman, Caroline Champion writes about The Dumb Waiter, which is a film which clearly made an impression on her, and she’s right that the ambiguous ending (she reads it as more so than I did, or at least than I did on my first viewing) is the reason the film does stick in the mind, and not just because of Bierman’s assured handling of the mechanics of suspense. In addition, the booklet has credits for each film, transfer notes and stills.

There’s plenty of life in the short film beyond often brief runs in cinemas, and the best stay in the memory longer than the features they supported. This is the BFI’s second Short Sharp Shocks compilation and there’s certainly scope for many more.

|