|

Jane Giles and Ali Catterall’s documentary Scala!!! sets out its stall with a very long subtitle: Or, the incredibly strange rise and fall of the world's wildest cinema and how it influenced a mixed-up generation of weirdos and misfits. And that says it all, pretty much, though the film does a very entertaining job of expanding on it in just over an hour and a half.

Repertory cinemas are nothing new. The rather emphatically named The Film Society opened its doors in 1925 and during its existence. did much to expand the films available to its London clientele – including showing work which wasn’t then in distribution and in some cases not yet passed by the British censor. One of its double bills is memorialised in another BFI release: Battleship Potemkin and Drifters, released on disc as part of a series significantly called The Soviet Influence. The Everyman in Hampstead (which no doubt could do with its own documentary, though I suspect that will be rather different to this one) opened its doors in 1933. The National Film Theatre (NFT) followed in 1951. When I began London cinemagoing in the early 1980s, there were several rep houses, charging a nominal membership fee and showing different double and triple bills each day, with some small-scale first runs. Due to their club status, they could show films without BBFC certificates with their local authorities’ consent, though with the Everyman, for example, that often meant showings of Yasujirō Ozu films which hadn’t then been submitted to the Board and which would not receive, and indeed have not received, anything higher than a PG certificate. However, as we will see, the Scala in particular would show films which pushed at the limit of what could be shown to the public in a British cinema.

As I’ve already mentioned myself, I’ll go on to say that I visited many of these cinemas: the ones mentioned above and others such as the Roxie on Wardour Street (which often showed music-based films – I first saw Woodstock there). Some first-run cinemas included repertory in their programmes: I saw quite a lot for the first time at the Gate Notting Hill’s Sunday matinee double bills in the late 1980s to early 1990s. I was a Friend of the Everyman when that membership scheme was in operation, and I was and remain a BFI member. I was also a member of the Scala, of which more in a moment.

By the end of the 1980s, the repertory scene was in decline. The rise of home video made available many of the films that you previously couldn’t have seen anywhere other than in a cinema. (Let’s face it, many of the Scala’s staples wouldn’t then have been shown on television in a month of Sundays and quite a few of them wouldn’t now.) Television channels, such as the fledgling Channel 4 and strands such as BBC2’s Moviedrome – compered by Alex Cox and later Mark Cousins – expanded what could be seen on the small screen. While VHS resolution by no means matched that of 35mm, or even that of 16mm or standard-definition television, those cult films were often in better shape than the beat-up prints doing the rep rounds. Nowadays, many of these venues have closed. The NFT, now called the BFI Southbank, continues to show a wide range of films from all eras and all over the world on its four screens. The Everyman in 2000 became a first-run two-screen cinema, which it remains to this day. The Scala closed its doors in 1993. Something of the spirit of these cinemas lives on in, say, the Prince Charles, just off Leicester Square, which shows a changing programme of films sometimes on first runs, in other cases having just finished them, with showings of older classics and cult films and special event screenings, in its two screens.

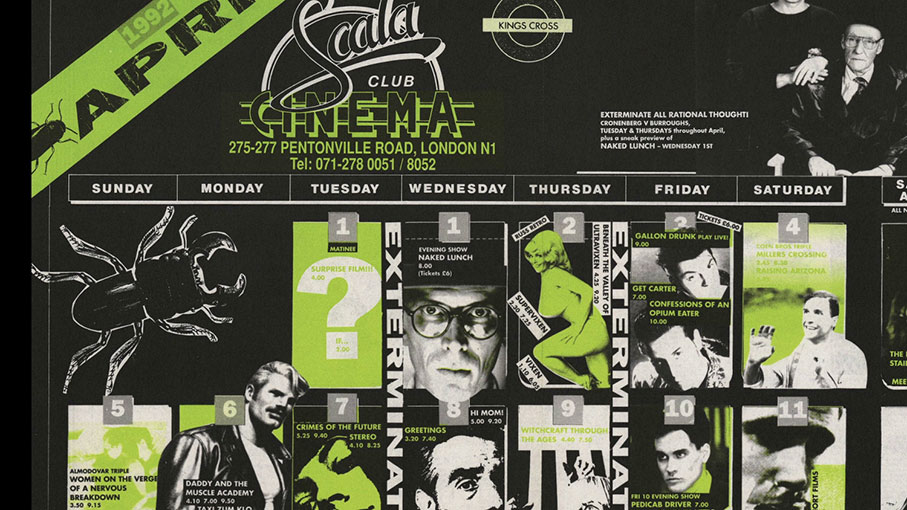

The Scala was originally in Tottenham Street in Fitzrovia, before moving to its familiar home in Pentonville Road, King’s Cross – ironically when Channel 4 took over the original building. The new site, previously called the King’s Cross Cinema and then known as the Gaumont, can be seen in The Ladykillers. It set itself up as an anti-NFT, showing films that the then more staid organisation wouldn’t normally touch, mixing arthouse and world cinema classics with exploitation, finding a beauty in what could be called pulp or trash. The cinema’s sensibility rode the waves of punk and LGBT activism, in the latter case with a well-known gay pub, The Bell, just up the road. You could feel the rumble of the Northern Line under your not especially comfortable seats, and the cinema’s cats would roam the aisles, often jumping on to the laps of unsuspecting filmgoers. (The one I remember was called Warren, and when he died the cinema put on a tribute screening of his favourite film, The Evil Dead.)

Laurel and Hardy all-dayers rubbed shoulders with kung fu and – making full use of its club status – culty underground hardcore porn such as Curt McDowell’s Thundercrack! (1975) and Café Flesh (1982), directed by Stephen Sayadian under the nom de smut Rinse Dream. In the former case, the Scala had one of just five 16mm prints ever known to have been struck, and one of the even fewer at the full length of 159 minutes. Shown frequently, by the time the cinema closed it was so battered that it barely got through the projector and the distinctly rough soundtrack and the Scala’s notably lo-fi sound system made much of the dialogue incomprehensible. The Scala was also the venue for festivals such as the all-day-and-all-night horror binge Shock Around the Clock and three- or four-feature horror previews on New Year’s Day. It also hosted live gigs: the Tottenham Road site now has a blue plaque (which we can see in the film being unveiled by Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore) commemorating the two nights in 1972 when Lou Reed and Iggy Pop and the Stooges played there, Mick Rock’s photographs from the gigs being used for the covers of their albums Transformer and Raw Power. But just as importantly were the audiences, many of whom have gone on to careers in the arts and activism. That also applied to some of the staff.

I was a Scala member, from the mid 1980s to the end. Whether I count as a weirdo or a misfit, is not for me to say. As I didn’t and don’t live or work in London, I wasn’t there as often as some people, but did go there fairly often. I commuted from my place of further education (Southampton) for the Deadly Day of De Palma, showcasing the last showing of Dressed to Kill before it (then) went out of distribution, as the fifth of a quintuple bill with Obsession, Carrie, Sisters (or Blood Sisters as it was then known in the UK) and Blow Out. There were many other showings I could name.

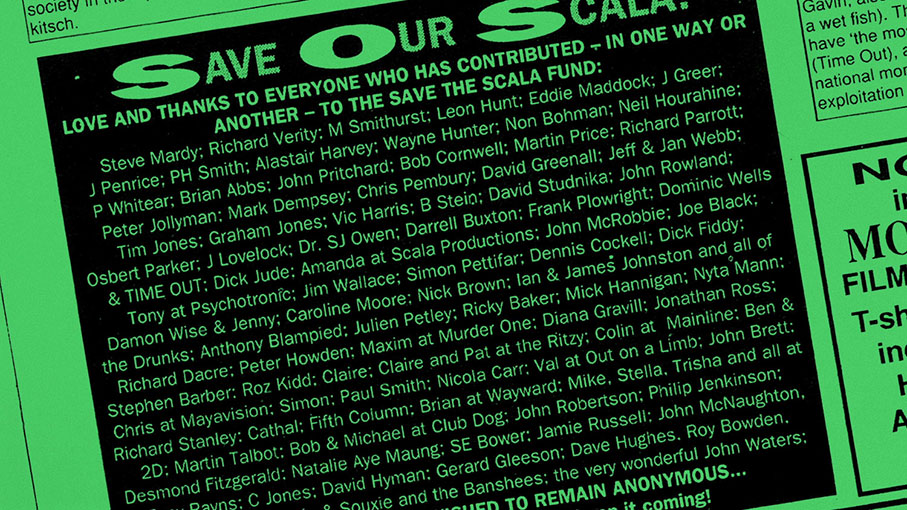

However, towards the end of the 1980s, if you looked closely the writing was on the wall. King’s Cross had become an increasingly dangerous part of the city – an area where I witnessed people walking Rottweilers on string leads – and the cinema, generally run on a pittance, was becoming increasingly run down. The rise of home video, and the increasing availability of some of the films which had been the cinema’s stock in trade, began to affect the audience turnout. Also, the lease was shortly to expire. The cinema showed, more than once, A Clockwork Orange (at least once billed as “a timely and fruitful surprise”), and as a result was sued by Warner Bros as the film was then completely withdrawn from UK distribution at the behest of Stanley Kubrick, and remained so until after his death in 1999. Despite what some have claimed, that didn’t finish off the cinema, though the legal costs depleted its resources (if you contributed to the Save Our Scala fund, you may see your name on screen eighty-one minutes in). The Scala closed in 1993, with a showing of the film which had been the first it had ever put on, the 1933 King Kong. The building reopened in 1999 as the nightclub and live music venue it still is. However, the Scala had made a permanent mark in British film culture, and the ongoing Scalarama festival helps it live on in the memories or those who were there and as an inspiration to those who were not.

Scala!!! tells this story with a combination of archive footage, film clips, still photographs, some animations (by Osbert Parker) and cartoons (Davey Jones) filling in accounts of events for which no visual record exists. (In some cases, you might be glad of that – one man standing up in the auditorium and pissing over those in front of him, and programmer JoAnne Sellar’s having to deal with a dead body found in the cinema.) In addition to these, there are new and archive interviews with those who were there, as staff, as festival programmers and as those having formative experiences while in the audience. One of them is Jane Giles, who is very much a part of the film’s history, as a participant, the writer of the book on which the film is based, and the co-director of said film itself.

Scala!!! is a Blu-ray release from the BFI, encoded for Region B only. The film has an 18 certificate, which is partly explained by some fleeting real sex in clips from Thundercrack! However, you can see a retro 1970s red X certificate during the opening credits, which is authentic to the point of having signatures from Lord Harlech and Stephen Murphy. The Thundercrack! clips apart, you can see this film getting an X without much problem in the 1970s or 1980s. The short films Relax, Flames of Passion and Coping with Cupid have 15, PG and 12 certificates respectively.

The Blu-ray transfer is in the aspect ratio of 1.78:1. The production was entirely digital, as were cinema showings, other than the fact that the many film extracts were from features and shorts shot in 35mm or sometimes 16mm (Pink Flamingos, Thundercrack!) and some of the archive material was clearly shot on video. There’s nothing much to say except that this no doubt looks the same as it would do in a cinema projected from a DCP (with the proviso that I haven’t seen the film in a cinema), which is as it should be.

The soundtrack is rendered in DTS-HD MA 5.1. AAs the majority of film extracts have monophonic soundtracks (and as the cinema never stretched to a Dolby system, the stereo films – such as The Thing – played there in mono anyway) and much of the rest of the film is talking heads, so the only real surround use is the music score and the subwoofer more or less gets time off. There is also an audio-descriptive soundtrack in DTS 2.0, and English subtitles for the hard-of-hearing are available on the feature only.

Commentary by Jane Giles and Ali Catterall

It’s a good question as to how easy it is to provide a commentary track for a documentary, and that’s one that this track doesn’t really answer. The rapport between Giles and Catterall is obvious (you can hear drink cans opening at the very start), but far too much of it simply describes what’s on screen. There is useful information to be had as the two occasionally fill in things not entirely spelled out on screen: for example, which film of John Waters that he had the experience of watching with the Scala audience. (Hairspray, for the record.)

Scala Interviews (59:51)

An hour’s worth of deleted scenes, more from the various interviewees: Peter Strickland, Douglas Hart (billed as a filmmaker but equally well known as a member of The Jesus and Mary Chain), Beeban Kidron (who gets a subsection on the scarcity of women filmmakers – scenes from her film Antonia and Jane were shot at the Scala), Mary Harron, Caroline Catz, Jane Giles, Kim Newman, Bal Croce (who programmed psychotronic events and tells a hilarious story about an Edward D. Wood Jr presentation involving one of Wood’s producers), Stewart Lee, Adam Buxton and Stephen Woolley. Much of this could easily have been retained in the film itself, if two and a half hours of it might have been too much of a good thing.

Scala (35:08)

Also called Scala, but without the three exclamation marks and the extensive subtitle, this was directed on video by Michael Clifford in 1990 for the Cable London channel. Some of this film is used in the main feature as archive footage. Beginning with one of the Northern Line trains which used to rumble under the building’s foundations. The camera wanders around the building, taking in the auditorium, the cafe, the box office and the projection box, including some appropriate film clips and featuring interviews with inevitably young-looking Jane Giles, Stephen Woolley and others...including Scala habitué Mrs Maureen Reeve, who often attended with her son and is revealed in the end credits of the main feature to have lived to a very ripe old age (1914-2022), passing away while the film was in post-production.

Scala Cinema (3:46)

An amateur film shot on video by Aly Peck and Victor de Jesus in 1992, this begins with commters leaving King’s Cross underground station before taking a short walk from there to the cinema itself. Inside the building, we see the ticket office, the projection box and the auditorium. Very rough and ready compared to the other documentaries on this disc, it is still valuable first-person testimony of this cinema.

London Film Festival Introduction (12:24)

On 15 October 2023, Jason Wood takes to the stage to introduce the London Film Festival showing of Scala!!! He is then joined by Jane Giles, who takes a shot of the audience on her phone, and then Ali Catterall, who does the same on his. They call out members of the crew from the audience and ask those who appear in the film to join them on stage. Then anyone who ever worked there gets to stand up, at the programme leaflet designers, then anyone who ever went, anyone who worked on the film in any capacity or contributed to its Kickstarter, and finally the few in the audience not included above. So the film receives a standing ovation before it starts.

Animations by Osbert Parker

Three short items with a Play All option: “Scala Programmes” (1:37), “Primatarium” (0:54) and “Tentacles” (1:19). All three of these feature in the film itself, but play out a bit longer here. The first animates some of the programme leaflets that adorned many a wall in the 1980s and early 1990s (mine included). The second covers the building’s life before it became the Scala, when for a year it was the Primatarium, an exhibition devoted to apes and featuring a real waterfall in the auditorium. The final item dramatises an episode involving an unfortunate intake of hallucinogenic mushrooms by cinema staff.

Cartoons by Davey Jones (3:10)

As well as Parker’s animations, some episodes where no footage (still or moving) exists to illustrate them are recreated by Viz cartoonist Jones, who we see talking about his work as he creates it.

Short Films

Three short films which played at the Scala and which were popular with its audiences.

Relax (23:17)

Relax is a short film directed by Christopher Newby in 1991, before his feature films Anchoress and Madagascar Skin. Steve (Philip Rosch) has had multiple partners and worries that he might have contracted HIV so at the encouragement of his lover Ned (Grant Oatley) he gets tested. But what he can’t do is relax… Shot in black and white 16mm (with some colour inserts of blood corpuscles running through veins), Relax is an engaging short which must surely have struck a few nerves with its audience at the time it was made. It’s presented in a ratio of 1.55:1 (14:9), which was not a cinema ratio but is explained by its Channel 4 funding – that was a halfway house between the old 4:3 and the widescreen TV 16:9, used when widescreen televisions were not available and not yet widespread, so as to provide a wide image without too-thick black bars on older sets.

Flames of Passion (17:50)

From 1989, Richard Kwietniowski’s short, subtitled A Seven Day Pass, is a gay update and homage to Brief Encounter, which is a film with gay subtexts for the taking, given Noel Coward’s presence as screenwriter. As with the original, so with this: encounters at British Rail stations, all shot in black and white (16mm again). Presented in 1.33:1, which is also appropriate to the original.

Coping with Cupid (18:56)

Written and directed by Viv Albertine, then best known as the guitarist for The Slits and now an author, Coping with Cupid was shot in 16mm colour in 1991. It appeared as an extra on the BFI’s release of Radio On. Among its Scala showings was as part of a triple bill with Cafe Flesh and Russ Meyer’s Up! That’s no doubt a very strange programme, as Coping with Cupid is very much influenced by film theory and has Brechtian alienation effects thrown in. Three aliens arrive on Earth in the form of three blonde women (Yolande Brener, Fiona Dennison, Melissa Milo) sent here to investigate what humans mean by love. The fact that the form they take is one of femininity to the max (big hair, tight dresses, high heels, lots of makeup) is no accident. Along the way the three aliens meet psychoanalyst Liz Green, feminist writer Ros Coward, film historian John Noble, and, on a television screen, sexuality researcher Shere Hite. It’s funny, which is in its favour. Presented in 1.33:1.

Scala Programmes 1978-1993 (12:03)

Jane Giles in voiceover takes us through fifteen years of Scala programme leaflets, one a year. They begin with the plain black and white of the Tottenham Road years before they quickly morph into the well-remembered layout. These leaflets include advertisements for the films the cinema occasionally showed as first runs, beginning with the Edie Sedgwick documentary Ciao! Manhattan. We also see listings for benefit screenings, the first appearance of festivals such as Shock Around the Clock and a whole month (April 1993) when each day’s viewing was sponsored by various parties in an effort to help the then-beleagured cinema. Plenty of memories to be had here.

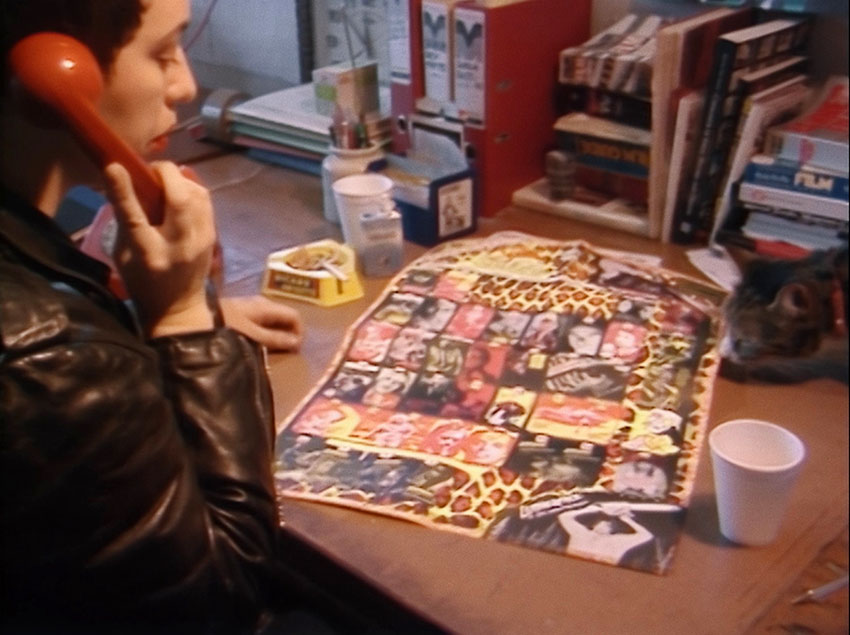

Cabinet of Curiosities (17:58)

Jane Giles in voiceover again, this time taking in some items and memorabilia for the cinema over the years, from the red telephone and card index of contacts via which films were booked. Piles of books, often used as reference, from the academic to the less so, distributors’ catalogues and ledgers and audience survey returns, the membership rules. It’s all here, including the book revealing box office takings, some high, less so, with breakeven reckoned at around £5000 a week. There is even a letter from local MP Chris Smith expressing sympathy for the cinema’s imminent closure, but I suspect not doing much more than that. Also included are boxes for the medium that was a factor in the decline in repertory cinema audiences, home video of The Evil Dead and Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! It ends with a clapperboard for the main feature itself.

Trailer (1:41)

A rapidly-edited condensation of the film, which gives you a good idea of what to expect in the full hour and a half.

Booklet

The BFI’s booklet, available in the first pressing of this release only, runs to thirty-two pages. After a brief directors’ statement, the lead piece is also by Giles and Catterall, positioning their film as a paean to a time and a place – and given that the majority of Scala attendees were school- or student-age a place to find yourself and those like you, and to form lifelong attachments. An essay which is more or less the feature in microcosm, though without the film clips.

After two pages of credits for the main feature, “Scala Spirit 1993-2003” begins with Giles again, setting the scene for short pieces by the Scala programmers over the years, all of whom have gone on to work in the film industry (Stephen Woolley, Jayne Pilling, JoAnne Sellar, Mark Valen, Giles herself and Helen de Witt), all asked to pick films made after the cinema’s demise which they would have put on. The booklet continues with credits for and notes on the extras on this disc and four pages by Osbert Parker on his animations included in the film and among the disc’s special features, including the logistics of wrangling stop-motion octopus tentacles which soon began to stink under the lights.

The best documentaries about institutions capture a time and a place, and that’s something Scala!!! does admirably. It makes a case for the cinema being a significant part of British cultural life and one whose influence is wide and ongoing, well captured on this Blu-ray and its extras.

|