|

If you’ve somehow never heard of The Pemini Organisation then worry not, as you’re by no means alone. It was founded by three friends – Peter Crane, Michael Sloan, and Nigel Hodgson, hence Pe Mi Ni – in 1972 when they were in their early twenties and Crane and Hodgson were fresh out of film school. Only three films were produced under the Pemini banner, and each is remarkable in its own way, not least for the fact that these relatively inexperienced young men were able to persuade top-flight actors to star in works whose budgets wouldn’t cover the average music video catering bill. All three were written by Sloan and directed by Crane – Hodgson admits that his role was more as a general assistant on the first film and that his involvement in the company quickly waned due to the demands of his full-time job and his recent marriage.

That these films effectively dropped off the radar shortly after their release is one thing, but that the original negatives and almost all theatrical prints were also lost is another entirely. The films themselves were certainly new to me, and the clear aim of this new, two-disc Blu-ray set is to bring these unfairly overlooked works to the attention of modern audience. But Indicator have gone the extra kilometre and then some here, as will become clear when I get to special features that have swallowed up most of my free time for the past couple of weeks. But first, to the films themselves.

Here’s the setup. John Drummond (Edward Woodward) has approached London estate agent Margaret Lord (June Ritchie) about renting a small first floor office, and as the film begins they enter the proposed establishment so that John can see if it meets his needs.

And that’s all I can safely say. The problem when discussing any of the films here is that screenwriter Michael Sloane has quite a way with narrative twists, leading you down a path that then suddenly forks off in an unexpected direction, only to then take a different fork later. Given that this is one of this film’s strengths and pleasures, expanding on the above does mean revealing the first of this film’s twists, but it does occur early and is foreshadowed from the moment John walks into the empty office. If you want to go in completely cold, then skip the next paragraph and approach the rest with caution, as it’s hard to talk about the film in any detail at all without dropping hints about where it later heads.

It’s clear from the moment that the John and Margaret enter the empty office that something’s not quite right about John. There’s a slightly guarded edge to his side of their seemingly amiable conversation, as if what he’s saying does not reflect what is going on inside his head. This peaks when he gazes distractedly through the window at the street below and confirms that this room is in the ideal location. The ideal location for what, exactly? He then suggests that maybe he doesn’t want to rent the office after all, and that perhaps this was all just a ruse to be alone with Margaret. Impressively, she’s not remotely phased by this, a subtle suggestion that she’s heard and never swallowed this unconvincing attempt at a chat-up line before. But for me, what set the alarm bells ringing was the case that John has with him and protectively holds onto, as if fearful that it might be suddenly pulled from his grasp. This is not a regular business attaché case, and to someone who’s seen his share of thrillers, its elongated shape instantly suggested that it housed a firearm, probably a rifle. I didn’t have to wait long to have this confirmed. Just eight minutes into the film, John locks the door to prevent Margaret leaving, and her continued refusal to be intimidated falters sharply when John explicitly states that he’ll kill anyone who tries to forcibly enter the room. “I don’t want to hurt you,” he tells Margaret as he slowly advances on her. “I don’t want to touch you. I don’t even want to see you. I just need you to be here with me.” A short while later he asks Margaret the precise time, then opens the case and assembles a double-barrelled shotgun. From that point on, the tension over what might unfold doesn’t waver for a second.

Anyone looking for evidence that the foundation of a successful drama lies in the screenplay will find plenty to bolster their case in Sloan’s tightly written script for Hunted. It’s not surprising that he, Crane and Hodgson were able to pique the interest of actors of the calibre of Woodward and Ritchie, despite their inexperience and a starting budget of just £1,000. The quality of the dialogue gives the actors so much to work with, something particularly true of a monologue delivered by John as he reflects on an incident in his childhood that may have shaped him into the man he has become. But both actors are impeccably served here, and both respond with performances that I would rank amongst the best of their careers.

For a first-time director, Crane already has a clear command of his craft, making productive use of facial close-ups and even slow camera movements, which can’t have been easy to set up and execute in the small office location in which the film was largely shot. Only on a couple of occasions did I find myself questioning shot choices – one widely shot exchange in particular had me itching for an eye-level facial close-up that is surprisingly late in arriving. But such moments are rare and fleeting, and Crane not only builds the claustrophobic tension well, he delivers the surprise turns of Sloane’s script so effectively that twice they prompted a startled vocal response from me.

With its tightly structured 42-minute running time, its solitary location, and its compellingly written and delivered dialogue, there were times when Hunted feels almost like an episode of the prestigious ATV drama series Armchair Theatre. The ghost of a 1967 episode of that series, A Magnum for Schneider, certainly hovers distantly in the background here – it also starred Edward Woodward and became the launchpad for his career-defining role as an ice-cold government hitman in the brilliant Callan. It’s the air of lethal danger that Woodward brought to that role that underscores even his more quietly reflective moments of Hunted, giving the actor the opportunity to express a range of emotions, sometimes in the space of just a few seconds, something that Woodward carries off with aplomb. Equally impressive is June Ritchie as Margaret, confidently unflustered by John’s initial proclamations, while her palpable fear for his intentions is increasingly underscored by a growing and genuine concern for his welfare. The result is a hell of an achievement for a trio of 20-something first-timers, and thanks to the strength of Sloan’s script, the confidence of Crane’s direction, and the riveting performances of the two leads, coupled with an aspect of the story that seems even more grimly relevant than ever, it’s lost none of its power in the 50 years that have passed since it was made.

As unglamorous character introductions go, the one that precedes the opening titles of Assassin is a peach. In the black of night, a man whose name we never learn (played by Ian Hendry) lights a cigarette and enters a dark alleyway, where he’s instantly set upon by three men. He initially gives a good account of himself, fighting them off to the accompaniment of very period-specific action movie music. When one of them lands a serious punch and another cuts his hand with a broken bottle, however, he brings the fight to a sharp halt by pulling a handgun on the men, who rapidly flee. So far, so Hollywood, you might think. But this is not America but early 1970s Britain, and the fact that this man is carrying a gun indicates that he is likely either a criminal or… what was that title again?

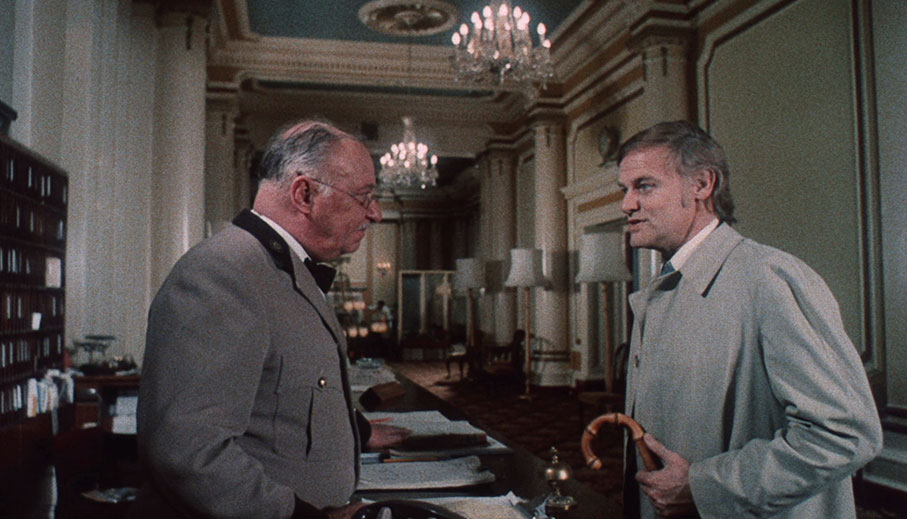

What follows is a sequence constructed entirely from close-ups that inform us that we are (probably) in the world of spies and espionage. Files are taken from a desk drawer and opened, pictures are taken on one of those pocket cameras that you only see being used covertly in films, a recording is played on a tiny tape hidden inside a razor, a microfilm is retrieved from hidden door inside an AA battery, and a small wad of pound notes are handed over to a second party. Presumably as a consequence of this skulduggery, a man known only as Control (Edward Judd) is called and asked to arrange the liquidation of John Stacy (Frank Windsor), a senior official at the Air Ministry who has been identified as the source of damaging leaks. The voice on the phone wants Stacy killed the following day at a wedding reception at which he is the best man, and he wants Control’s best for this job. This means that Control will not be using his usual operatives, the biblically named Matthew (Mike Pratt) and Luke (Frank Duncan), but an outside contractor. I wonder who that could be.

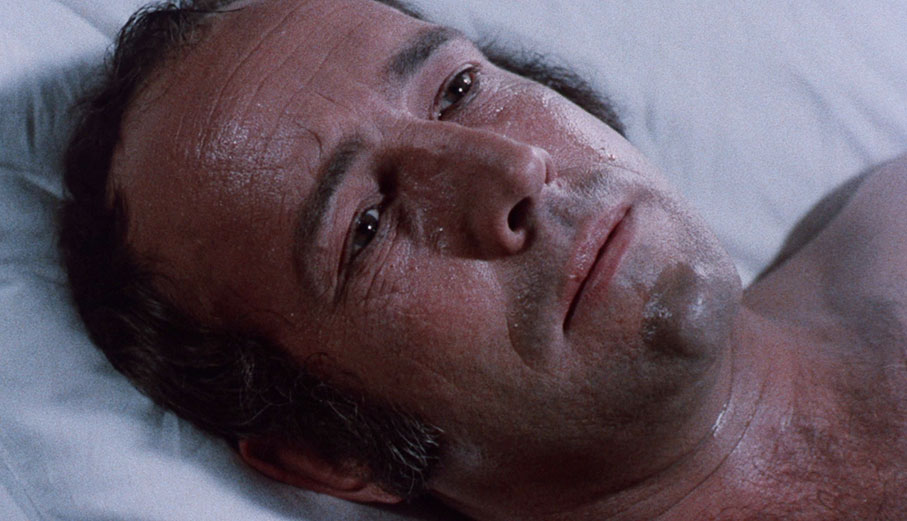

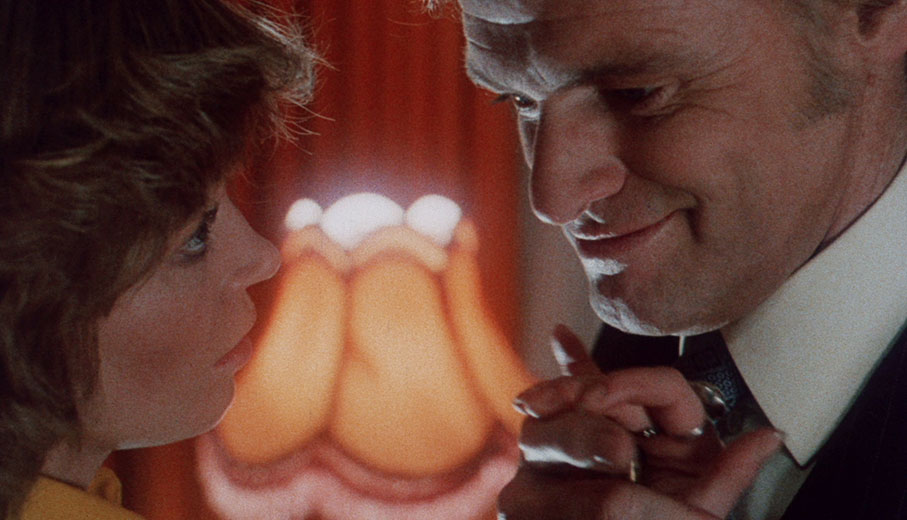

For Sloan and Crane, Assassin represents a considerable expansion in scale over Hunted, being a feature-length project with a far larger cast and crew and multiple locations, including shoots at Heathrow Airport and on the London Underground. But this is still every inch a low budget independent work, but also one that is, I would humbly suggest, more clearly the result of a director who is still learning the finer points of his craft. Whereas in Hunted the camera placement almost invisibly served the characters and story, in Assassin Crane sometimes experiments with angles and lenses in a way that can’t help but draw attention to the filmmaking in a way that suggests a secondary meaning to shots that may have been chosen simply because they were visually interesting. Then again, maybe not, as despite its setup, Assassin is not a thriller in the conventional sense but an existential character study, a tale of two men whose fates become fatally intertwined on the whim of an unseen official in a position of presumably governmental power. And these are, on the surface, two very different individuals. The Assassin is a loner who is tortured by an incident from his past, one that haunts his dreams from which he wakes in a cold sweat and that appears to be feeding his increasing doubts about his profession and his growing desire to retire. When asked by Control how many men he’s killed, he deflects by throwing the question back at his employer, suggesting that the man has lost count of the people whose deaths he has ordered and that he sees them only as a statistic. “One of the these days there’s going to a minute breakdown in your intimate machinery,” The Assassin tells Control, “and one of us is going to come all the way back to London and kill you.” Increasingly, however, it seems unlikely that The Assassin will be the one to do so. At one point a possible way forward for him does present itself when he meets an equally lonely woman in a bar (Verna Harvey) with whom he strikes up a conversation and ends up spending the night. The following morning she asks him to stay, but he insists on leaving anyway to complete his assignment, eventually reacting to her increasingly desperate pleas with an explosion of frustrated fury.

John Stacy, on the other hand, is a more gregarious family man who is about to be best man at wedding of his younger and newly promoted colleague Craig (Ray Brooks). Yet small hints soon surface that John’s relationship with Craig is not as rosy as this situation might suggest. When John’s secretary jokes that it’s Craig’s last night of freedom, for example, John initially reacts as if a dark secret has been exposed before realising she is referring to the final night of Craig’s bachelorhood. When John arrives (late) to the pub in which Craig’s stag do is under way, he has already sunk a can of beer at the office, and downs his first drink at the bar with the speed of a man who is trying to calm rattled nerves. Later, a drunken Craig accuses John of resenting the fact that his public school background counted more than John’s years of service when it came to the new job we can assume that they both applied for, something John makes no attempt to deny. There’s clearly some underlying bitterness here, which bubbles to the surface when Craig suggests that John has nothing to show for his years of service, which angers the older man because it’s probably true. Just what all this means, and how it might be set to affect the future of both men is never revealed. Could this be at the root of the termination order? To say more would mean revealing a pair of late-film twists, neither of which I saw coming.

For me, Assassin is the sort of film that really benefits from a second viewing, as it’s then that my initial uncertainties about some elements were countered by small details that I previously missed and dots that I failed to connect the first time around. The cast is once again first rate, with the always excellent Ian Hendry gives a thoughtful and subtly tortured performance as The Assassin, his uncertainty about continuing with work that he no longer feels committed to showing on his face and in his body language in every scene. Not bad for an actor who was reportedly seven sheets to the wind for almost the entire shoot. There’s solid support from Frank Windsor as John Stacy, a man clearly wrestling with unspecified demons of his own, and as the ambitious Craig, Ray Brooks nails the barely concealed smugness of a man convinced he is superior to people he cynically calls his friends. There’s a whole other movie in the backstory of these two.

Assassin takes the core elements of a political thriller, strips them down to their bare essentials and makes the differing worlds of the hunter and his target its prime focus. The unhurried pace at which it unfolds may have come in for some criticism on its initial release, but as someone who has become increasingly weary of the perceived need to ramp up the speed of seemingly every scene in a movie, I continue to treasure the films of this period for their refusal to rush and their willingness to allow scenes and characters to breathe.

I will admit that a couple of things don’t quite click for me. The late film flashback to the confrontation that so haunts The Assassin is well staged and exciting, but I did wonder whether what unfolds there would really give a man who kills for a living sleepless nights, and fuel a growing disenchantment with his profession. Then again, in the way this film has of prompting you to dig below the surface, I began to wonder if the incident in question was the back-breaking straw in a career peppered with similarly unfortunate encounters. There’s a twist in the final scenes that did feel a teeny bit contrived, and I’m still not sure about the odd couple pairing of Matthew and Luke, the former a cockney wide boy who gets a kick out of his work, the latter an aristocratically smug product of the public school system. They’re the only ones here who feel a little like movie constructs, but I still couldn't help thinking that there was genuine TV series potential in the mismatch of their backgrounds, personalities, and approach to their work.

Ultimately, however, these are minor quibbles when it comes to this intriguing and quietly haunting study of a troubled hunter and his prey. I’ll admit that of the three films here, Assassin is the only one I didn’t instantly connect with, but when I did I found myself repeatedly drawn back to it, each time finding new small details in the dialogue, the performances or the direction that changed how I viewed a specific scene or character or the film as a whole. And if you enjoy films whose character backstories are inferred rather than openly stated, and which slyly invite you to expand on the small details and subtle suggestions provided, you should have a ball here.

As a small sidenote, those who sit patiently through the final credits may notice a now familiar name fulfilling the role of assistant editor on both this film and Moments, a man who later went on to become one of this country’s most successful and celebrated producers and whose life and work was recently celebrated by Mark Cousins in the excellent documentary, The Storms of Jeremy Thomas.

A well-dressed but sad-looking businessman named Peter Samuelson (Keith Michell) travels by train to off-season Eastbourne to check in at The Grand Hotel, the location of happy holidays in his youth. As he approaches the hotel entrance, an energetic young girl named Chrissy Hunter (Angharad Rees) bumps into him, then quickly apologises and goes on her way.

At the reception desk, Peter is greeted by head porter, Mr Fleming (Bill Fraser), whom he still remembers from his childhood visits, something that appears to warm Fleming’s heart. Once installed in his room, Peter unpacks and lays out his possessions in an orderly fashion, then takes out a revolver and puts it to his head. Before he can pull the trigger, however, he is interrupted by a relentless hammering on his door. Unable to ignore it or convince this unwanted visitor to leave, he answers the door and is confronted by an energetically upbeat Chrissy, who is on a desperate search for matches to light a gas fire in her room to ward off the cold, and John being one of only a handful of other guests. The distracted Peter is eventually able to assist, but Chrissy also needs his help getting the fire lit, and is even worried that she left the gas switched on. The two thus sprint up to the next floor to her room, where Peter lends the required assistance and the effervescent Chrissy chats relentlessly to him, inviting him to stay and even offering to share her takeaway meal. Initially Peter is reluctant, but over the course of that night the two get to know each other better, and he finds himself slowly becoming attracted to this life-affirming young woman.

It seems clear from an early stage that Moments is going to be a tonally different film to Assassin whilst remaining recognisably the work of the same writer-director team. This is particularly evident in Michael Sloan’s screenplay, whose dialogue is simultaneously thoughtful and believable, and whose later twists really do catch you by surprise, whilst make also making sense of elements that you might have found yourself previously questioning the plausibility of. I’m going to make an odd comparison here (go with me on this), but those who have seen Ueda Shin'ichirō’s superb One Cut of the Dead will doubtless remember how those oddly hesitant and awkward moments in the first half are so deftly explained by what happens in the second. Despite the fact that these are two very different films whose plot twist in no way overlap, the same process of revelation happens here. More than once I found myself thinking, “Would she really do that in this situation?” or similar, only to find myself twenty minutes later looking back at this moment armed with new information that made complete sense of the whole thing. Or does it? Just when you think you’ve found your feet, you’re given cause to rethink preceding events again, and none of these twists ever strain credibility. It all just works, and sublimely so.

Crane’s direction is completely character focussed here, with his camera placement and editing decisions (real props to cinematographer Wolfgang Suschitzky and editor Roy Watts on this score) admirably serving the emotional journey that Peter takes over the course of the story. Gone are the experimental angles of Assassin, not, I would suggest, because Crane elected to reign them in, but because it’s here that he found his true directorial voice. In Moments, his work on previous two films melds into a harmonious whole, allowing him to integrate flashbacks and hallucinations and at one point have Peter come close to interacting with his childhood self, all without disrupting the narrative flow.

The performances of the two leads are impeccable. Keith Michell, who at the time was riding high on his success in a recurring role as Henry VIII on TV, is quietly a superb here, his inward trauma subtly expressed through both his facial expressions and his hesitant, slightly awkward body language, an aspect that Michell apparently brought to the role. Providing an ebullient flipside to his melancholia is Angharad Rees as Chrissy, a lively ball of upbeat energy of the sort that I initially found myself thinking only seemed to exist in movies, but once again by the time I hit the halfway mark I was given good cause to revise that view. Also shining here is Bill Fraser, an actor known primarily (though not exclusively) for his comedy work and who turns in a wonderfully low-key performance as long-standing head porter, Mr. Fleming.

Age-gap friendships (in which the man is almost always older than the woman) that may or may not develop into something more intimate may not have been new ground in 1974 – Clint Eastwood’s third film as director, Breezy, which had this character dynamic at its core, was released the previous year – but it’s what Sloan and Crane do with the concept and how oddly believable it all feels that stand this film apart. In some ways, it’s the personality chasm that initially divides these two individuals that makes their journey together so touching, as the suicidal Peter is dragged back into the light by Chrissy’s unwaveringly positive energy, only to then have to deal with revelations that change how both he and we regard her and their evolving relationship.

I’ll admit to being oddly apprehensive about Moments, at least before I sat down to watch it, the brief plot synopsis I had restricted myself to not having quite the same instant hook as the one for Assassin. Yet even before Peter puts the gun to his head in his ultimately disrupted suicide attempt I was hooked, and my attention never wavered for a second. It’s a seriously well written, well acted and well directed film, and for my money is where the considerable talents of Sloan, Crane and their dedicated collaborators most fluidly coalesce. The only small blip is no fault of the filmmakers, but a scene that was removed at the behest of the distributor in their pursuit of an ‘A’ certificate, the film elements for which have now been sadly lost. It’s briefly referred to in the dialogue, but is such a key moment that its absence is felt – handily, an analogue tape copy has been included on this disc as a deleted scene.

Hunted, Assassin and Moments were all restored by Final Frame Post in London from 35mm distribution prints preserved at the BFI National Archive. As is made clear in the booklet and in the disc-based special features, all the prints had significant problems, including – and I’m quoting verbatim here – missing or torn frames, continuous surface scratches, irregular abrasions, heavy dirt, frame warps, shrinkage, adhesive residue, creasing, split perforations, dye stains, and oil spots. Bloody hell. The work required to remove much of this was clearly extensive and must have taken an age – check out the restoration featurettes included in this set – but the one type of damage that could not be digitally cleaned up is that of missing frames, particularly with only a single film source to draw from. Fortunately, Peter Crane and Michael Sloan had SD tape copies of the films in their complete form, and these were used to replace the missing material. This does mean that the image seems to ‘pop’ into a lower resolution version for a second or two in places, which is caused by the resolution drop from 35mm film to SD video tape. It’s a small price to pay to see all three films in their complete form, or at least as complete as they were on their original theatrical release.

Hunted was shot on 16mm and blown up to 35mm for theatrical distribution, and this is instantly evident in the very prominent film grain. In other respects it’s in remarkably good shape, with the considerable amount of dust and damage that blighted the film print almost completely eradicated, and the image is now rock steady in the 1.66:1 frame. The colour has that slightly dour documentary look common to British film-shot work of the era, and the contrast is nicely balanced, with decent shadow detail and solid black levels. Considering the enlargement from 16mm to 35mm, the detail is well defined, only dropping on the odd shot where the camera focus was just off, something I never found remotely distracting. The tape inserts are more visible on this film than on the others, primarily because there appear to be more of them here, but again they’re not a problem and are very cleanly integrated.

Assassin was shot on 35mm, and while the film grain is still clearly visible, it is finer than on Hunted and the image detail is definitely crisper, something particularly evident in the close-ups of Ian Hendry’s face, which are often pin-sharp. Although retaining the realist look of Hunted, the colour here is a little richer, notably on primes or on coloured lighting. The contrast is again nicely balanced, capturing the expressionistic gloom of a London that looks about as inviting as I remember it being back then, without the darker picture elements being swallowed by the solidly rendered blacks, except when elemnts are deliberately pulled into noirish shadow. Damage and dust have been cleaned up, and while some traces of former wear are still visible, particularly on uncluttered areas of single colour, they have been reduced to a level where there do not distract. The framing here is 1.75:1.

Moments was also shot on 35mm and is also framed 1.75:1, and has a slightly softer look to the image than Assassin, but this oddly seems to suit the tone of the drama. Detail is nonetheless for the most part well defined, and while the colour has a sometimes almost period hue – shaped I suspect by the décor of the hotel – the brighter colours are handsomely realised, as evidenced by a sequence set inside an amusement arcade. Again, dust and damage have been cleaned up, and there’s a gentleness to the contrast balance that really works for the film without softening the black levels.

All three films sport Linear PCM 1.0 soundtracks that have also undergone restoration. None have the sort of crystal clarity you’d expect from even a microbudget movie today, and the dynamic range is unsurprisingly narrow, but the dialogue is always clearly audible, and although occasional signs of former wear are still just audible in the background on some scenes, any serious damage has been effectively repaired.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are available for all three films should you require them.

DISC 1

Audio Commentary on Hunted with Peter Crane and Sam Dunn

The first of three commentaries featuring the film’s director Peter Crane and film historian Sam Dunn sets the tone for them all in being hugely informative and consistently fascinating – Crane is an enthralling storyteller and Dunn an excellent feed man, asking the sort of questions that prompt detailed and revealing answers. Covered here is how the Pemini Organisation came to be, how they procured the services of actors of the calibre of Woodward and Ritchie and what he learned from working with them, the lost prologue sequence (more on that below) and why it was added, the importance of the quality of Michael Sloan’s screenplay in getting the film made, the true-life incidents from which some aspects were drawn, why the film was initially refused even an ‘X’ certificate, and much more. We learn about the unexpectedly important role played by Crane’s job as a soda jerk at the Yankee Doodle Burger Bar, and how he got to work on movies whilst at film school by choosing sound recordist as his preferred specialisation, primarily because nobody else wanted to do that. This really resonated with me, as there was only one student in my year at film school who chose to specialise in sound recording, and he worked on everything as a result.

Audio Commentary on Assassin with Peter Crane and Sam Dunn

This second commentary track with Crane and Dunn proves to be every bit as enthralling as the first, and this film’s longer running time allows Crane to cover more ground and dive even deeper into some areas. Topics discussed include the how they were able to cast Ian Hendry in the lead role (this is really interesting), the challenges of being freed from shooting in a single location, his first time working with union crew members, Sloan’s subsequent success in Hollywood and his insistence on casting Edward Woodward in The Equalizer, how Hunted acting as a calling card when approaching actors, and more. The role the Yankee Doodle Burger Bar played in getting this film made is expanded on, there’s an amusing anecdote about Crane’s encounter with a naked Helen Mirren, and a fair few stories about Ian Hendry’s heavy drinking, including how he was having vodka smuggled onto the set by his regular stand-in and how this impacted on his fellow performers.

Hunted: The Lost Prologue (9:44)

The voice of Peter Crane recalls the lost opening sequence of Hunted, his words illustrated with stills of the shoot, film extracts, and scans of documents. A nicely assembled featurette that paints a clear picture of how the sequence would have played out and how it relates to the main drama, as well as providing some useful snippets about the filming itself.

Peter Crane: Organising Principles(31:29)

A welcome video interview with Peter Crane, who I have to say looked nothing like the picture I had formed in my head of him from the commentary tracks. He outlines how a teenage fear of exam failure prompted a change of direction that ultimately led to him becoming a director and subsequently a painter. There is inevitably some crossover with the commentaries (mostly the one for Hunted), but there’s still so much that is new here that this proves enthralling nonetheless. Of particular interest are Crane’s memories of directing episodes of various American TV series, how different the methods of production there were to independent features, and how he had to quickly learn the process and adapt to avoid being fired on his first day. There are some engaging anecdotes here, but the moment that really struck a chord with me is the story of why he refused to screen dailies for the cast and crew on his first two films, one that directly mirrors the reason my fellow reviewer Camus elected to do likewise on his film, Kelling Brae.

Michael Sloan: An Amazing Time (6:24)

A brief chat with Pemini co-founder and screenwriter writer Michael Sloan, who recalls meeting Peter Crane and shooting the three Pemeni films, before they went their separate ways and he later teamed up with Crane and Edward Woodward again on The Equalizer. He doesn’t go into depth on any of the discussed points, but does express a lasting fondness for the three films in this set.

Nigel Hodgson: Good Chemistry (29:01)

A longer and more revealing chat with Pemini co-founder Nigel Hodgson, who is engagingly self-effacing from the off about his contribution to the making of Hunted and Assassin, describing himself as more of a handyman who drove people around because he had a job and a car. He tells the now familiar story of how he, Crane and Sloan met, but from a different perspective, and expands usefully on a film he made with Crane in Scotland while at film school and the shooting of their graduation film, In Search of Lebanon, which has been included in this release. There’s a dryly comic moment when he offhandedly describes The Pemini Organisation as “second only to Warner Brothers,” anecdotes about filming in Heathrow Airport overnight and having to drive a boisterously drunk Ian Hendry home, and we get the full story of how he met and started dating the woman who would become his wife. I enjoyed this.

June Ritchie: A Group of Friends (13:53)

Actor June Ritchie tells the story of how she was first approached by a young and hopeful Michael Sloan with the script for Hunted and how the production eventually came together. She admits to being initially nervous of working with an actor of Edward Woodward’s standing, and also that “it was quite frightening – he’s a bloody good actor.” She admits to only recently having seen the completed version and being impressed by the power of the final scene, and muses sadly on how much more relevant the story the film tells has become in recent years.

Graham Dee: Scoring with Gerry (12:03)

Veteran Soho musician Graham Dee recalls how he met Sloan, Crane and Hodgson through the Yankee Doodle Burger Bar, as well as his working relationship with top music arranger Gerry Shury on In Search of Lebanon and later on Hunted. The part of his story I found myself wanting to know more about comes when Dee left for American between the two films and ended up working as a rancher. It was while he was doing this that he received a letter from Crane and Hodgson asking him to come back to the UK and score Hunted for them, and for a fee that only paid half of his air fare. Having watched the film again for the first time in decades, he concludes that score still sounds alright. “Good old Gerry,” he modestly says.

Martyn Chillmaid: The Life of My Memories (21:47)

Martyn Chillmaid recalls being a film student when Peter Crane joined the faculty as a lecturer, and being one of three students recruited to crew Hunted, on which he worked as assistant director, before going on to serve as second assistant on Assassin and stills photographer for part of the shoot on Moments. He provides more detail on the filming of the now lost prologue to Hunted, and has nothing but praise for Edward Woodward’s friendliness to this young and inexperienced crew. He’s also not the first to tell stories of Ian Henry’s drinking and the problems it created, though one involving a bus and a female conductor who recognised him did amuse me.

Gabriel Hershman: Assassin’s Creed (22:01)

Gabriel Hershman, author of the biography Send in the Clowns: The Yo Yo Life of Ian Hendry, provides a welcome overview of Hendry’s career, from his early TV roles (let’s not forget that he was the lead player in the first series of The Avengers), through his kitchen sink dramas in the 60s and the villainous roles that became his forte, to the waning of his career in the 70s and 80s. Inevitably, his heavy drinking and its impact on his life and work comes up but is not dwelt on, Hershman being more interested in what made Henry such an arresting screen presence, and why he never became an international star. The interview is illustrated with clips from several of Hendry’s works, not a straightforward task when you presumably have to negotiate the rights for each of them.

Restoring Hunted and Assassin (4:45)

A brief but welcome featurette showcasing the digital restoration work done by Final Frame Post in London on the prints of Hunted and Assassin held by the BFI National Archive, both of which had suffered considerable wear. Placing the original and restored version of the same sequence side-by-side makes it easy to appreciate how much work has gone into this, something particularly true of scratches across faces – even repairing them on still imagery is a challenge, and I’m speaking from the voice of experience. The replacement of missing footage with frames from the analogue video copies of the films is also illustrated here.

Hunted Image Gallery

100 screens of often excellent quality production stills – including a sizeable number of behind-the-scenes shots (they actually outnumber the promotional photos) – and press book scans.

There are three Assassin image galleries. Promotional Material consists of 80 screens of crisp monochrome and colour promotional stills, the cover and pages from a nicely designed press book that is presented as a secret dossier, and a single magazine poster. Behind the Scenes features a whopping 211 screens of the filmmakers and actors at work or prepping for shots, including some revealing photos of the rigs used to attach the camera and lights to cars or the back of a van (or in one case, the roof of a Tube train). Again there’s a roughly even mix of monochrome and colour shots. Finally, Script Gallery consists of 25 pages of scans of Michael Sloan’s script, two pages per screen, the first page of which is signed by Ian Hendry

DISC 2

Audio Commentary on Moments with Peter Crane and Sam Dunn

The last of the three commentaries with Crane and Dunn upholds the standard set by its predecessors, blending information on the making of this film with career stories whose chronological coverage make this at times play like a British Entertainment History Project interview, and a damned good one. Areas covered by Crane include how this third and final Pemini film came about, the casting of the lead roles, working with his first full union crew, how securing the location impacted on the shooting schedule, the influence of European filmmakers like Visconti and Resnais, the technical challenges that filming in hotel rooms with a large and heavy Mitchell 35mm camera created, and much more. He acknowledges the help provided by his three assistant directors, explains why one pivotal sequence had to be altered at the last minute and why it was ultimately cut from the film, and reveals why and how The Pemini Organisation then ceased to be. There are some really interesting anecdotes about the shoot itself, a fascinating story about a distribution deal for all three films that ended up in a court case (which includes a detail about the distributor’s office that is directly echoed in the early episodes of Better Call Saul), and Crane is of the opinion that this was the film on which it really all came together for him artistically, a point on which I am in complete agreement. One thing that makes these commentaries so enjoyable is Crane’s complete lack of ego – for him, these films were a collaborative learning process that could not have come together were it not for the efforts of the talented people he worked with. I was also so relieved that the late film discussion on his career is paused at the last second to allow him to explain how the extraordinary final shot was achieved.

The BEHP Interview with Wolfgang Suschitzky (92:25)

A typically thorough British Entertainment History Project audio interview with Moments cinematographer Wolfgang Suschitzky, who recalls his early days in pre-WW2 Vienna and his emigration to Britain, and traces to his move into film camerawork and his work on short films and features. Many of the films he worked on are covered in detail, including some of the technical aspects of photographing them, and while I was left itching to know more about the making of Get Carter and Theatre of Blood, I did smile at the news that one of his most enjoyable jobs was the filming of three seasons of Worzel Gummidge for TV. He seems to have stayed true to his father’s socialist roots and is saddened that the film union has lost much of its power, and reveals the root of his engaging modesty when he says, “I don’t like people who brag all the time – there are directors who think they are the answer to our prayers.” Unfortunately Hunted gets no specific coverage, being brushed over in a single sentence about only shooting short films and commercials in his later years. I’d also have been interested to hear him talk a bit about the work of his son, Peter Suschitzky, who followed in his father’s footsteps and has now become a cinematographer of considerable note, in no small part due to the films he shot for David Cronenberg.

Peter Crane: Moments in Cannes (7:35)

Director Peter Crane here recalls the positive reviews the film garnered, and how the countrywide release that should have built on this good word was undermined by an IRA bombing campaign that saw a massive drop in cinema attendance. He tells an amusing story about a screening at Cannes that potential buyers walked out of in droves, and how investor and producer David M. Jackson responded to this by breaking into fits of nervous laughter. He also notes the award nominations the film received and how this convinced the filmmakers that they’d done something right, and that Moments marked his real graduation from film school.

Valerie Minifie: A Present Out of the Blue (6:15)

Actor Valerie Minifie, who plays Peter’s wife in a few brief hallucinatory sequences (some of which were subsequently cut from the film), recalls getting the offer from her agent to work on Moments, as well as some aspects of the shoot itself. This is interesting in part because it adds details not touched on in the commentary track – only shooting at weekends due to Keith Michell starring in a stage musical during the week, for example – although some specifics of her last-minute casting recalled by Peter Crane are not touched on at all here.

John Cameron: Reality and Non-Reality (13:42)

Composer John Cameron – whose credits include Kes, The Ruling Class, Psychomania, Who?, and many more – has fuzzy recollections of first meeting director Crane, but clear memories of how he approached the score for Moments, including the creation of the more abstract musical riffs. He admits to ensuring that any source music used is always authentic to the time and place in which the scene in question is set, and sees his role as a collaborative one – you do whatever it takes to make the film work.

Bill Summers: Shooting with Mr Su (10:28)

Bill Summers recalls working on many commercials with director of photography Wolfgang Suschitzky and being asked by him to join the crew of Moments as his gaffer, and if that term is unfamiliar to you then you’re likely to be left bemused by some of the other technical terms that Summers uses here. Having a background in lighting camerawork this was all familiar territory for me, but Summers gives no quarter here, reeling off the names of lights used as if planning glossary pages for American Cinematographer. There is still plenty of interest for the uninitiated here, with technical aspects and the challenges of lighting the locations covered, and Suschitzky sound like the nicest person in the world to work for.

Bruce Atkins: Nothing’s Going to Stop Us (15:09)

Landscape photographer Bruce Atkins looks back at his student days and how he ended up working as a production designer on the three films directed by then visiting lecturer Peter Crane. He concisely recalls the relationship with the actors on Hunted and how the young crew members were all learning their craft on the hoof, how Assassin was a step up from that film and how Hendry could put all of his problems on hold as soon as the camera rolled. He talks specifics about two particularly difficult shots in Moments, and looks back at the making of that film as a life-changing experience. He highlights the meticulous safety precautions taken by the German armourer on the films, and has a few engaging anecdotes about the various shoots, including being charged by a herd of deer when filming in Scotland.

James Partridge: A Family Affair (21:42)

Peter Crane’s cousin, James Partridge, talks about being brought in as a general assistant on Assassin and graduating to the art department. It’s a job he also did on Moments, at least until an extended rail strike landed him with the task of driving the newly shot footage to London to be processed and the resulting rushes back to Eastbourne each day. He shares some specifics about his work on both films and on the filming of the prologue for Hunted in Scotland, and contributes a previously untold story about Ian Hendry’s drinking (I get the sense that everyone who worked on Assassin who is interviewed was asked about this) that explains a moment when The Assassin fumbles the task of shutting his gun case. He precisely echoes Bruce Atkins, however, when he notes that however much drink Hendry had consumed, as soon as he heard the word “Action!” he was a different man, a consummate professional.

Vic Pratt: The Whole Story (16:23)

Film historian Vic Pratt – who we can never now forget was also the stripped-to-his-underwear star of The Adventures of a Plumber in Outer Space – looks at the history and output of The Pemini Organisation and how its story is effectively bookended by Edward Woodward. It’s perhaps a tad unfortunate that much of what is said here will be old news if you’ve been watching and listening to the special features in the order listed here, but there are still some interesting extra details, including quotes from contemporary reviews and from Edward Woodward. He is of the opinion that Assassin is the company’s masterpiece, a point on which we may have to differ, though give me a few more viewings and that may change. If you’ve just finished watching the films, I’d suggest this is a good place to start with the special features, as it concisely wraps up information that is expanded on elsewhere.

Deleted Scenes (13:33)

An up-front caption reveals that the only two surviving versions of Moments are a 35mm distribution print preserved in the BFI National Archive and a copy on analogue U-matic tape owned by the filmmakers, which contains the original cut of the film, before changes were demanded by the distributor to secure the more family-friendly ‘A’ certificate. Three sequences are featured here, all of which are shown as they appear in the theatrical cut, then how they played in the original edit. The first two are alternative edits of existing sequences, but the third was completely excised from the theatrical release at the behest of the distributor, and involves a sex scene that is intercut with memories and which makes more sense of a development that is otherwise only obliquely referenced in two short lines of dialogue. A hugely valuable inclusion.

Moments Image Gallery

45 screens of promotional stills (including shots from the delete scenes), production photos, press kit scans, a screening invitation, a pocket watch-shaped press release (this is really neat), what looks like pages and the cover of a photo album styled promotional package (again, very nice), a brief related story from the awful Daily Express, the artwork that features in the film (which was painted by Keith Michell) and a poster. There’s some interesting material in here.

Restoring Moments (5:01)

In a similar manner to the restoration featurette on Disc 1, shots from the archive 35mm print are positioned side-by-side with the results of the restoration, including a sequence that had been badly repaired and needed inserts from the filmmakers’ U-matic video copy to reassemble and restore. Again, a most worthwhile inclusion.

In Search of Lebanon (1970) (11:20)

Referenced several times in the special features, this film was made by Peter Crane and Nigel Hodgson when they were students at the Polytechnic School of Photography, one that played a key role in the eventual launch of The Pemini Organisation. It’s a semi-experimental travelogue exploring the notion of Lebanon as a modern-day incarnation of the Greek myth of the goddess Aphrodite and Adonis, poetically vocalised by Tony Richards’ narration. This has not undergone the same level of restoration as the features, and damage to the picture and soundtrack is still very evident, but this is still a welcome inclusion and adds to the completist feel of this release.

Also included is an 80-page Book, which includes full credits for the three films, each of which is followed by an essay by their director Peter Crane, which summarises information found in the on-disc special features (particularly Crane’s commentary) whilst also expanding on some aspects and exploring areas not covered elsewhere. All of these make for fascinating reading. Immediately after each of these essays are reproductions of the text from the Pemini’s own publicity material, providing information on the work and careers of the principal cast members of the film in question. Following this is another essay by Peter Crane, this time talking a detailed look at the last days of The Pemini Organisation and what ultimately brought the partnership to a close. Once again, this acts as both a round-up and an expansion on information delivered in Crane’s commentary tracks. Next is a piece I genuinely couldn’t have predicted, a 1975 article from The Guardian exploring Moments producer David Jackson’s efforts to become a motorcycle stunt performer and his plans to steal famed daredevil Evel Knievel’s thunder. I’ll leave you to discover how that one played out. The main credits and a summary of In Search of Lebanon are followed by a busy two pages of details about the restorations. There’s also an official introduction to the Pemini Organisation and a chronology of its activities.

This is exactly the sort of package for which we, as film enthusiasts, will forever be in debt to independent distributors like Indicator for. I’m sure I’m not the only one who was unaware of the existence of these films before the announcement of this release, and after watching every film and special feature in the package, I found myself wondering just how many other fascinating works are still buried in the archives, unseen for decades and awaiting revival and restoration (if you want to see more, the BFI’s excellent Flipside titles are a great place to start). This extraordinary release is a testament to the dedication and sheer love of film of not just the filmmakers, but those who so painstakingly restored the films and spent so much time shooting interviews, recording commentaries, and putting this tremendous 2-disc set together. I think we, as consumers (and reviewers) sometimes forget how much effort must go into creating special editions like this, and if ever there was a release to remind you of that fact, then one built around films made by similarly minded individuals working on minimal budgets, fired primarily by their talent and their passion for the medium, is most definitely it. I’ll accept that opinions will differ on the films themselves, but I thought they were really something, and this 2-disc set is as close to a definitive release as you’re likely ever to see for all three. Magnificent work all round. Very highly recommended.

|