|

Part 3: The Blu-ray

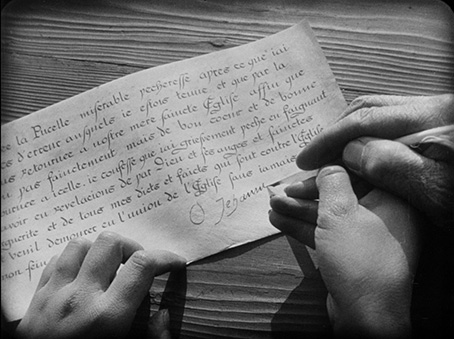

I could reword this, but it seems more logical to quote the accompanying booklet for details of the restoration:

This edition of The Passion of Joan of Arc was sourced from a 35mm dupe negative made from the original 1928 Danish preservation materials held at the Danish Film Institute. The film was scanned at 2K resolution on a pin-registered Arriscan film scanner and graded on a Nucoda Film Master.

Restoration work was completed in 1080Psf HD resolution using a combination of software tools and techniques. Thousands of incidences of dirt, scratches and debris were painstakingly removed frame by frame. Warped, damaged, or missing frames were removed or reduced, and density issues exhibited through excessive flicker were significantly improved. Stability issues demonstrated through bumps on film joins and dipping frame lines were also reduced. Throughout the restoration process, work was performed carefully to ensure that the film's original grain structure remained unaffected.

It's unrealistic to expect a film made in 1928 whose original negative was destroyed in a fire to look pristine, even after the restoration work detailed above, particularly when you consider that until 1981 Dreyer's original cut was thought to be a lost film. So yes, there's still a trace of the sort of image flickering that you often find on silent films and a few remaining visible signs of previous damage, but in all other respects the restoration has produced some remarkable results. The contrast and the tonal range of the greyscale are often sublime and the level of detail on the best material is striking for a work of this vintage and history. This is particularly evident in Dreyer's famed use of facial close-ups, where the textures of skin, hair and clothing frequently bely the film's age. There is little sign of the frame jitter we once took for granted on film prints of this age, and the slight vignetting evident throughout appears to be part of the process of filming rather than any fault of the print or transfer.

The above comments refer to the restored versions of the film; the Lo Duca version has, perhaps unsurprisingly, not undergone any major restoration, and thus functions as a useful comparison piece, not just in artistic terms, but also to illustrate how good the digital restoration is. The detail is actually better than you might expect, but the contrast has none of the subtlety and texture of the restored version, the damage is more visible (and extensive) and the image jumps around a little more in frame.

The soundtracks on all three versions of the film are linear PCM 48 2.0. As you would expect from more recently recorded tracks, the clarity and range on both the 2005 Mie Yanashita and the 2001 Loren Connors scores is first rate. Both appear to be stereo, although this is only clearly evident on the Connors music, where the separation is clear; the Yanashita score is piano only.

The mono score on the Lo Duca cut of the film is considerably older and not in such good shape, having a far narrower dynamic range and subject to wear and damage, the sometimes severe background hiss joined by a few pops and cracks.

| the booklet and the music |

|

The discovery of the original version of The Passion of Joan of Arc in 1981 was a significant event in the history of cinema, and the Masters of Cinema release of Dreyer's film feels like an important event in itself. This elegantly designed, built-to-last box set would be an essential purchase even if it contained just the immaculately restored 'Oslo' print of the film. That it also affords us the opportunity to consider the original version at both 20 and 24fps, with or without musical accompaniment, and compare it to the 1951 Lo Duca version, makes it astonishingly good value for money.

My preference is for the original version, screened silent and at 20fps. The film looked ridiculously fast when played at 24fps, while the mere suggestion of music felt like a crass intrusion on the images. I am reminded of Henri Langlois' mission to educate the eye at the Cinémathèque Française, and of his high-minded habit of screening Buster Keaton films with Czech subtitles. Langlois was dismissive of all who complained: "If they don't get Keaton without subtitles, well . . ." Many of us feel much same about Dreyer: "If they don't get Dreyer without music, well . . ." There will, undoubtedly, be those for whom time drags at 20fps, and those for whom music has to be 'in the mix' for them to feel the film's full dramatic impact, but, hey, each to their own.

Dreyer himself felt that music in modern films was too often merely camouflage for the poverty and artificiality of their emotional values. He was as appalled by the Lo Duca version – with its glutinous dollops of baroque classical – as he was powerless to prevent its distribution. As Casper Tybjerg points out in the booklet, Gaumont made a 16mm print of the Lo Duca version in 1956 and, without intentional cruelty, sent it to Dreyer as a gift. In a polite but strained reply, he wrote: "Trust me, the silence of the silent version would make a greater impact on the audience than the violent fortissimo of the music chosen here." Much as we mourn Dreyer, we can be thankful he was spared the experience of hearing the electronic score created by Loren Connors for the 24fps option. The fortissimo of the Lo Duca version seems like a sotto voce sigh beside the booming basso profundo of Connors' avant-garde arrangement, which is both perfectly in synch with the film's radical experimental ethos, and destructively obtrusive. By way of contrast, Mie Yanashita's delicate and conservative piano arrangement for the 20fps option is both entirely in keeping with the presentation style of the silent era, and completely at odds with the film's atmosphere of edgy innovation.

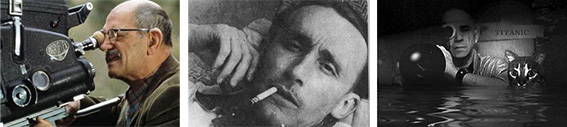

Regardless of our views on those versions, the range of choices offered is impressive. It is fascinating to compare those different viewing experiences. And, as if five very different versions of Dreyer's extraordinary film were not enough, the box set also contains a 100-page booklet that would be worth buying in itself. It opens with an extract from My Only Great Passion: The Life and Films of Carl Th. Dreyer by Jean Drum and her late husband, Professor Dale D. Drum. Having fallen in love with Dreyer's films in the early 60s, the two Drums were determined to produce the first English-language life of Dryer. They first learnt Danish, then moved to Denmark with their three children for several months. While there they conducted eight substantial interviews with Dreyer, and numerous interviews with his associates. They also conducted fact-finding trips to London, Paris, and Stockholm. Their encyclopaedic knowledge of Dreyer's work shines through here as they detail the film's production history and neatly summarize Dreyer's methods. This lengthy extract from their book stresses the importance to Dreyer of a universal sense of the struggle between conviction and dogma. It also includes a telling quote in which Dreyer defends himself against spurious charges of cruelty to his actors.

The booklet next treats us to a poetic contemporary review of The Passion of Joan of Arc by Imagist poet Hilda Doolittle, later to become a key figure for second-wave feminism. An acolyte of Ezra Pound (to whom she was briefly engaged) Doolittle shows little of Imagism's inclination to cut words back to the bone here. Instead, she is moved to unleash an alliterative rush of words in breathless praise of the film. It is a vivacious piece of writing that strains to understand the film's imposing power. In crying out, "This film feels too viscerally real. This must be the one and only Joan," Doolittle asks what happens to our historical imaginations if we allow Dreyer's vision of Joan to stand in for our own. She thereby raises the consequent question of where hagiography leaves us, which in turn sends us back to Brecht's The Life of Galileo for answers. In Brecht's play the astronomer's former pupil Andrea Sarti says, "Pity the land that has no heroes," to which Galileo replies: "No, pity the land that has need of a hero."

After Doolittle's thought-provoking review, three towering giants of cinema offer their thoughts on The Passion of Joan of Arc: none other than Luis Buñuel, André Bazin, and Chris Marker. Merely to see those three names together on a page is enough to set the pulse racing, and the insights they offer into Dreyer are as penetrating as one would expect. Besides being one of the great filmmakers of his generation, and a significant influence on Dreyer, Buñuel was a brilliant film critic whose writings on cinema were often as startlingly original as his films. That he more than holds his own with Bazin here, though, has as much to do with the frustratingly slight piece in the booklet by the French master critic as it does to the Spaniard's insights. Eureka have served up such a feast of films, ideas, and information in this single beautiful box that it seems greedy and ungrateful to ask for more, but, the bite-size morsel of Bazin we are offered merely piques our insatiable appetite for his thought. It would, for instance, have been satisfying to see Bazin's description of The Passion of Joan of Arc as "a documentary of faces" set alongside his views on realism in cinema. It would have been interesting, too, had the editors of the booklet found space for Bazin's views on the Lo Duca version, and not just because Bazin founded Cahiers du cinéma with Lo Duca in the same year the latter's notorious version of Dreyer's film was released.

Such quibbles immediately seem embarrassingly churlish when the booklet moves from that snippet of Bazin to the substantial piece by Marker discussed above, and they recede from the mind with the inclusion of Dreyer's own thoughts on his trademark style of 'psychological realism' or 'realised mysticism'. Dreyer frequently contradicted himself and often had one eye on his public image when he spoke, so we must take him with a pinch of salt. Fortunately, reading between the lines of his interviews is always interesting. Dreyer always denied that Day of Wrath was intended as a metaphor for the Nazi occupation of Denmark, but, when asked, here, about his 'Jesus of Nazareth' project, he says he began to see parallels between the Romans and the Danes, Pontius Pilate and Renthe-Fink, just days after Nazi invasion of 9 April 1940. He also says that he hoped to stamp out that prejudice which painted Jesus as blonde and Aryan.

After Dreyer in his own words, we are next treated to Antonin Artaud expressing his enormous respect for Dreyer. Artaud compares the experience of playing Massieu in The Passion of Joan of Arc favourably with that of playing Marat in Abel Gance's Napoléon and Mahaud in Marcel L'Herbier's L'Argent (1928). Artaud stresses the freedom Dreyer allowed his actors to explore their roles. In this respect, Baard Owe, who plays Erland Jansson in Gertrud, echoes Artaud almost word for word in Christiane Habich and Reinhardt Wulf's documentary Carl Th. Dreyer und Gertrud (1994). The impression given by all the actors who worked under Dreyer is of the Dane as a gentle guiding hand rather than an imperious iron fist. The booklet closes with scholarly notes by Casper Tybjerg on the various versions of the film, and a short note on the restoration of the original.

This lavishly illustrated and extensively footnoted biblio is a worthy addition to a wonderful package. Although the ideas of Ivor Montague and the Film Society movement have proved remarkably resilient, and although independent cinemas seem set to survive in our big cities, it seems inevitable that generations to come will discover 'cinema' at home alone rather than with others in darkened rooms on projection screens. Should that prove to be the case, we can but hope that classic cinema will be presented to the future with the kind of loving care evident here, and that it'll be appreciated the more fully due to the accuracy and appeal of the kind of information and ideas provided here. Congratulations and thanks to all at Eureka for a job well done.

< previous

Part 1 | Part 2 | Blu-ray details

|