|

Part 2

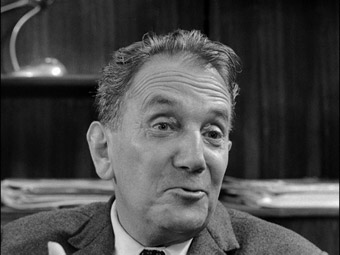

"When other people sit in the streetcar and look out of the window, I sit and look at

faces, old ladies and red-nosed men . . . I feel that throughout all time it is the human

face which has fascinated men the most, to see what goes on in the face of another

person . . . To make a face disclose what is taking place within, that is exhilarating." |

Carl Dreyer, from Ninka, 33 Portrætter,1969 |

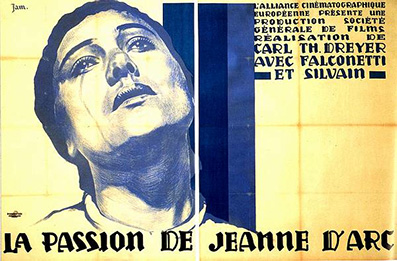

"With the exception of a few images, [The Passion of Joan of Arc] is completely

composed of close-ups, mainly of faces. This technique was in response to two objectives

ostensibly opposed, but, in fact, intimately connected: spirituality and realism . . .

Dreyer, for his part, regretted that he couldn't use sound, which was starting to

stammer in 1928. To those who still think that cinema left us when it started to talk,

we need reply with this masterpiece of silent cinema that is effectively talking already." |

André Bazin, from Radio-Cinéma-Télévision,1952 |

The magnificent booklet accompanying the Masters of Cinema release contains a 1953 essay by Chris Marker, in which he argues that the function of close-ups in The Passion of Joan of Arc is to locate the film in the present. Marker says: "The way in which Dreyer searches faces, the absence of make-up, are consequences of this necessity to place the story of Jeanne in the present, that is to say, in eternity, in order to make it tangible to the spectator even while diverting him from the reassuring framework of the past." Marker is right, but, despite Dreyer's refusal of the formulaic tropes of costume drama, and despite the modernity of the images he creates, the film is also enshrined in the past. It is both cemented within the cinematic cannon and caught up in cinema's miraculous capacity to make memory flesh and restore the dead to life before our eyes [Godard alludes to a heightened form of cinema's tendency to reawaken the past in Chapter 4a of Histoire(s) du cinéma, Le contrôle de l'universe, when he slyly says (with Kim Novak/Madeleine in Vertigo and Brigitte Federspiel/Inger in Ordet in mind) that Hitchcock was the only one, alongside Dreyer, to film a miracle]. The tension between past and present in The Passion of Joan of Arc is mirrored in that between realism and lyricism. The film also shaped film's future. Long before Arthur Miller's The Crucible, Michael Reeves' Witchfinder General, and Emile de Antonio's Point of Order, Dreyer showed us the injustice of institutional witchhunts in The Passion of Joan of Arc and Day of Wrath. Three decades before Marker's La Jetée, Dreyer's radical use of close-ups mapped new ways of representing human psychology and played with the subjective gaze. As André Bazin says: "Let there be no mistake, that prodigious fresco of heads is the very opposite of an actor's film. It is a documentary of faces." There are two accidental moments that make the film seem even more like a documentary: the moment early in the film when Joan is weeping at the memory of her mother and a fly flits onto her face, and that when another fly lands on her as she lies exhausted in her prison cell. It is amazing what the camera and close-ups can catch.

Writing from the vantage point of the sixties, the veteran French critic Roger Leenhardt noted in Cahiers du cinéma that one of the main arguments against CinemaScope was that it would do away with "the sacrosanct close-up . . . the means of psychologically delving into a character, of going into the soul with a camera." Leenhardt, who was a significant formative influence on Bazin and the Cahiers critics, regards that as "a total error." In his view, "An exaggerated close-up of a face is not psychological and complex but lyrical and elementary. Any woman's face, seen from very close, looks like – if that face is without make-up and the texture of the skin is a thousand times enlarged – Falconetti in The Passion of Joan of Arc." Leenhardt concludes that filmmakers had become tired of putting the same face on film, and tired of what was called pure cinema, because "all classical style is the same." Looking back on Leenhardt's comments from roughly the same distance as he himself was then looking back at Dreyer's film, we can conclude that Dreyer established classical cinematic style. We might add that Leenhardt established the New Wave when he founded Objectif 49 with Bresson and Cocteau, long before he appeared, as himself, in Godard's Une Femme Mariée (1964). We must further add that Henri Langlois laid down an equal claim when he set up the Cinémathèque Française with Franju and Mitry in 1938. Let's say, simply, that the respective acts of Langlois and Leenhardt, and the films of Dreyer, sit among those radical interventions that changed film culture forever. I'd now like to look at what influences worked on and through Dreyer, partly because Bazin's distinction between directors who put their faith in the image and those who put their faith in reality breaks down in Dreyer's case. Dreyer cuts across or straddles Bazin's divide.

In his 1929 New York Herald Tribune review of The Passion of Joan of Arc, titled A Dying Art Offers a Masterpiece, Richard Watts says: "Most (French) films have been almost unbelievably incompetent." He then claims that, with Dreyer's film, "French cinema art was born." The French film industry, it is true, was emerging from crisis as Watts wrote (in 1929 it produced just fifty films, by 1931 its output had doubled, and by 1933 it had tripled), but what it lacked in quantity it made up for in quality. We can but wonder if Watts had seen such experimental classics as Abel Gance's La Roue/The Wheel (1922), Jean Epstein's Cœur Fidèle/Faithful Heart (1923), and Fernand Legér's Ballet Méchanique (1924). We can safely assume Dreyer saw those films; their fame spread like wildfire among filmmakers, and their influence is apparent in The Passion of Joan of Arc. In his late silent classic, Dreyer deploys the extreme close-ups taken to new lengths by Epstein, makes the same extensive use Epstein and Gance did of rapid editing techniques, created rhythm from the repetition and disappearance of images as Gance and Legér did, and recreated the jagged edges of Cubism, Expressionism, and Vorticism as Epstein and Legér did. Later, in Vampyr (1932), Dreyer even replicates Epstein's superimpositions and innovation of shooting through gauze filters in order to create a hazy, dream-like atmosphere. It seemed more than happy accident that Michael Brooke's excellent article on versions of Dreyer's film appeared in Sight & Sound's December issue opposite an image of Gina Marnés from Cœur Fidèle.

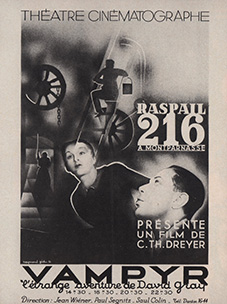

Nobody could accuse Dreyer of being a mere copyist. His radical originality was based on a deep knowledge and love of cinema evident from his first film onwards. Dreyer's political conservatism is a matter of record, but his politics were no more straightforward than his aesthetics. It is hard to beat Jonathan Rosenbaum's description of Dreyer as: "An obsessional artist who was an enemy of all institutions, cinematic as well as social, and whose principal theme was intolerance." Dreyer's hatred of anti-Semitism and his feminism, his thematic focus on religious and social hypocrisy, and his obsession with faith, choice, and suffering are all contained within Rosenbaum's neat characterization. Where cinema is concerned, the evidence points to significant ways in which avant-garde ideas and techniques infiltrated Dreyer's work. Although, he strenuously denied any avant-garde affiliations and tendencies, because conscious of the damage such associations might have on his already damaged reputation, his readiness to embrace the shock of the new is clear for all to see. It is writ large in Vampyr, his first sound film, with its eerie, indistinct soundtrack; its hazy, half-visible filtered sequences; its dancing shadows and startling superimpositions; its disorientating sets and gruesome deaths; and its blurring of the line between reality and illusion. Vampyr is an even stranger and more experimental film than The Passion of Joan of Arc. And this was Dreyer making, what he considered to be, a commercial film.

The work of the pioneers of silent cinema – Epstein, Gance, and Legér; the darker Germans Lang, Murnau, and Weiner; the Hollywood entertainers Chaplin, D.W. Griffiths, and Lubitsch; the Soviet innovators Eisenstein, Pudovkin, and Vertov; the soulful Swedes Sjöström, Stiller, and Brunius – all left their mark on Dreyer in their different ways. Dreyer's early work was, after all, formed in an atmosphere of feverish innovation, when a language of images was being invented on the hoof. While the deadening atmosphere of the laboratory often hung over the cinematic avant-garde of the 1920's, there was also an exciting energy about the way it exposed the clichés of silent film style. It was a period when the comparative cheapness and simplicity of silent film production allowed tight avant-garde units a measure of freedom to experiment and explore unusual subjects. It was also a period before big studios frowned on experimentation and opted for the formulaic, when, especially in Europe, they allowed daring directors complete control over their big budgets. Although he successfully sued Société Générale des Films, in 1931, over breech of his contract to make another film for them, Dreyer had every reason to be grateful to his producers for granting him a free hand to experiment at will. As Paul Rotha said in 1930: "With the exception of Société Générale des Films there exists no producing company in France that recognizes the artist-mind of the French director."

Dreyer had an insatiable curiosity and a broad, restless mind. He never stood still. He was always willing to learn from others, and from his own mistakes. Aside from Dreyer, perhaps only Godard – and, as Godard suggests, Rossellini and Welles – so consistently reinvented themselves and risked failure in search of new forms of expression. Technical advances in aviation fascinated Dreyer as a young man; as a director, he remained ever alert to technical and formal innovation in film. In the early stages of his itinerant career he was fortunate to find himself at the epicentre of eruptions of modernist experiment: while in Berlin to direct Die Gezeichnetten/Love One Another (1922), Mikaël (1924), and Master of the House (1925) he absorbed the radical cultural ferment of the Weimar years; after moving to Paris in 1926 to make The Passion of Joan of Arc, he immersed himself in the avant-garde. All his early enthusiasm for aviation was transferred to cinema, which he loved with a passion. In a 1950 interview for the radio programme New Perspectives in the Arts and Sciences, Dreyer was asked, "What is film to you?" He replied: "My only great passion." That passion was poured into every film he made and was reflected in his stewardship, between 1952 and 1968, of Copenhagen's renowned Dagmar Cinema.

Dreyer said, "It's from the daily grind of making films that you learn the craft." He certainly learned on the job, but he also learned from and tried out the experimental breakthroughs of others. He grew to maturity as a director during the 'Golden Age' of Swedish Cinema between 1917 and 1924. He drew inspiration from Weiner for his sets, there are traces of von Stroheim in his adept way with actors, and of Sjöström in his sense of atmosphere; but it was from Griffiths, in particular his use of rapid editing and accelerating montage in Intolerance (1919), that Dreyer says he learned most. It is a happy coincidence that intolerance was foremost among his themes. Griffith's film sits alongside Dreyer and Gance's films for Société Générale des Films as the biggest, bravest commercial flops of the silent era. Dreyer pays tribute to Griffith in Leaves of Satan's Blood by replicating the multi-levelled narrative techniques the American used in Intolerance. He wasn't alone in acknowledging a stylistic debt to Griffiths, whose film may have failed with audiences but who was the apotheosis of the formal possibilities of narrative editing in the early silent era . . . until The Passion of Joan of Arc. In a 1947 interview for the third edition of The Penguin Film Review, Dreyer tells critic Ragna Jackson that his own film was an attempt to stretch silent film to its limits of expression, almost anticipating what the cinema was to become with the added advantage of sound. Dreyer adds the caveat that films should have sufficient emotional strength to hold their audiences without the help of music and that music is too often used in films as mere camouflage for the poverty of their emotional values.

Abel Gance had also been impressed by the precision of Griffith's editing work, which he saw at first hand in 1921 during a visit to New York. Gance had planned a whistle-stop tour to promote his anti-war film J'Accuse (1919) but extended his stay on the invitation of Griffith and Lillian Gish, both of whom fell in love with Gance's film. When he returned to France, Gance radically re-cut his uneven Impressionist masterpiece La Roue. Of the finished film, Cocteau said: "There is cinema before and after La Roue just as there is painting before and after Piccasso." It was the film that persuaded Kurosawa to make films. Gance's revolutionary use of rapid, rhythmic cutting was as significant an influence on Cocteau, Dreyer, Epstein, and Legér in France as it was on Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Dovzehko, and Vertov in the Soviet Union. Dreyer et al constructed their architecturally exquisite cinematic monuments with new materials provided by others. As I said in my review of Epstein's Cœur Fidèle, innovation follows innovation and we can trace a line of experimental descent in French cinema from the work of Jean Epstein and Jean Cocteau, through Jean Renoir and Jean Vigo, to Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Melville. More widely, a similar lineage runs from the work of Griffith and Gance, through that of Epstein and Dreyer, to that of Antonioni and Angelopolous, and, finally, to the work of Haneke and Von Trier today. These cinematic touchstones were also experimental stepping stones.

| Dreyer's Only Great Passion |

|

It is fitting that Dreyer's final public act united him in common cause with two generations of directors – Chabrol, Godard, Rivette, and Truffaut; Gance, Rossellini and Welles – when, in February 1968, he added his signature to a petition forbidding the screening of their films at the Cinémathèque Française in defence of Henri Langlois' removal from his position there. In his biography of Godard, Everything is Cinema, Richard Roud calls the Cinémathèque "a cinematic Louvre." In L'Histoire(s) du cinema, Chapter 3a, Godard himself says of it: "One evening we turned up Chez Henri Langlois. And then there was light." Jean Renoir called it "the church for the movies." For Dreyer, as for Godard, cinema was a defining passion, a kind of religion and, to some degree, a substitute for meaningful relationships. Perhaps that can be said of all cinephiles, but for Dreyer more than most, cinema offered compensation for a lack or a loss of love. Be that as it may, it certainly adds specific meaning to Serge Daney's observation that, "A love of cinema desires only cinema, whereas passion is excessive: it wants cinema, but it wants cinema to become something else."

Godard/Karina/Dreyer

Dreyer was an intensely private, emotionally trouble man who seldom spoke of his formative years or his feelings. Deeply damaged by his childhood experiences, uncertain in his sexuality, and seemingly shy, Dreyer was guarded, reticent, even secretive. He let his films speak for him; perhaps he hid behind them. Dreyer said next to nothing about his childhood, nothing about his homosexual experiences of the early 30s, nothing about the breakdown that followed them, and nothing about the time he spent with his wife in a sanatorium in Silkeborg (close to the spot where Kaj Munk was shot by the Gestapo). Yet, as I said above, Dreyer's upbringing shaped his worldview and his work, therefore, it is important to look at it. Prior to the appearance of Maurice Drouzy's Carl Th. Dreyer Né Nilsson, biographical information was scarce. Critics were forced to deploy intelligent guesswork about his enigmatic personality based on circumstantial evidence, the testimony of contemporaries, and Dreyer's own rare comments about himself. Criticism is always about intelligent guesswork to some degree, but now that we have hard facts about Dreyer to work with, our guesswork ought to be more accurate.

| Drouzy on Dreyer's Formative Years |

|

This much had long been known: that Dreyer was, like Abel Gance and Lars Von Trier, the product of an extramarital affair. Drouzy furnishes us with the facts. Dreyer was born of a cross-class dalliance between his mother, Josefine Bernhardine Nilsson, a Swedish domestic worker, and Jens Christian Torp, a wealthy Danish landowner. The affair was almost certainly consummated at Torp's farm in Southern Sweden. When Nillson became pregnant Torp immediately despatched her to Copenhagen, arranging a domestic service position for her there. After his birth in 1889, the infant Dreyer was placed in a series of foster homes and, briefly, an orphanage. Eventually, a typographer, Carl Theodor Dreyer, and his wife, Marie Dreyer, answered an ad placed by Nillson in a local paper and agree to adopt the boy, for a fee. In early 1891, back in Sweden, Josefine Nillson desperately tried to abort a second pregnancy by cutting the heads off a box and a half of match, and eating them (a common practise among desperate women in the late 19th Century). She died a ghastly, excruciatingly painful death as a result of sulphur poisoning. Drouzy argues that this depressingly familiar tale of a working-class woman used and then cynically discarded by a predatory male of the ruling-class, Drouzy argues, explains much about Dreyer's thematic concerns. It certainly helps explain Dreyer’s hatred of bourgeois hypocrisy and his interest in the pain and injustice suffered by women who breech the repressive codes of patriarchal, nominally Christian societies.

Drouzy goes on to chart even more startling aspects of Dreyer's formative years that further support that theory. Drouzy paints a picture of Marie Dreyer as a cold, flinty, unyielding woman. Carl Dreyer Senior doesn't exactly come up smelling of roses either, but he is, at least, presented as an earnest freethinker. Dreyer himself said that Marie Dreyer always made him feel that he was there under sufferance, constantly reminded him that his mother had abandoned him and failed to provide for his sustenance, and regularly locked him in cupboards. Dreyer, Drouzy suggests, came to hate her and to idealize and idolize his biological mother. He exonerated his 'real' mother of all blame for the lovelessness of his childhood. When Marie Dreyer died in 1937, he refused to attend her funeral, saying she had long been dead for him and he fled the Dreyer household at the first opportunity. The emotional damage and pain implied by those facts were not all Dreyer had to contend with.

As if rejection by his nominal mother were not enough for a confused youngster to absorb, an even more destabilizing blow to his fragile inner life was to follow. In 1908, having just turned nineteen, Dreyer travelled to Sweden for the first time to discover what he could about his mother from his biological Swedish family. We cannot know with what thoughts, feelings and hopes the young Dreyer set out, but one doesn't have to be a practising psychoanalyst to image the traumatic impact it would have had upon him to discover the circumstances of his mother's death. Tears and suffering were not abstract ideas for Dreyer; their passage through him left their mark on his heart, his films, and his sorrowful features.

Maurice Drouzy divides Dreyer's characters into 'good mother'/'bad mother' types and suggests that we read Dreyer's career a monument to his mother. He invites us to tread new interpretive avenues, explore different feelings about Dreyer. We now watch Brigitte Federspiel as Inger in Ordet with fresh (Freudian) eyes. Whether we read Inger's resurrection as a wish fulfilment fantasy or not, she still seems as different to us now as she did when she appeared as lovelorn Martina in Gabriel Axel's Babette's Feast (1987). Yet just as surely as Henning Bendtsen's cinematography links Ordet, Gertrud, and Babette's Feast; as surely as he unites Axel, Dreyer, and Von Trier; so, Federspiel links us to Josefine Nilsson and to Dreyer's inner life. All the suffering women in Dreyer's films now seem linked to Dreyer's mother and his dreams of her: Nina Pens Rode's Gertrud – with her solitary suffering and rejection of unsatisfactory men; Astrid Holm's Ida – the doting, devoted mother driven to desperation in Master of the House; Brigitte Federspeil's Inger – the doting, devoted wife driven to death in childbirth in Ordet; Anna Svierkier as tortured, persecuted Herlof Morte in Day of Wrath, Renée Falconetti as tortured, persecuted Joan in The Passion of Joan of Arc – it all seems to point to Josefine Nillson. When Nina Pens Rod says in Gertrud: "I believe in the lust of the flesh and the irredeemable solitude of the soul," she may have been speaking delivering Dreyer's manifesto declaration on his mother's behalf – and so on. It all seems so obvious when you think of it: it's all about the memory of mother. Yet, it all seems too obvious too.

| The Energy of Youth. The Wisdom of Old Age |

|

In casting around for binding theories and explanations of Dreyer's complexity, we might, miss what's beneath our noses; but it is more likely that we'll miss that which is before our very eyes. Perhaps we could just as productively consider Dreyer's work within the framework of his relationships to his biological and adoptive fathers. We could, for instance, read Dreyer's political conservatism as a reaction to Carl Theodore Dreyer Senior's left-leaning politics, or suggest that Dreyer inherited his hatred of religious intolerance from his 'father'. Thomas Elsaesser notes, in his essay Cinephilia or the Uses of Disenchantment, that François Truffaut was "fatherless but oedipally fearless." The same can be said of Dreyer in the 20s. Truffaut's revolt against the 'cinéma de papa' and Dreyer's search for an ideal mother certainly represented two sides of the same parentless coin. We might equally well consider the gradual changes in Dreyer's style as part of the ageing process. Dreyer scholar Casper Tyberg suggests that Master of the House may be the fastest-cut Danish silent film, and there is nothing slow about The Passion of Joan of Arc and Vampyr. Perhaps, after that frenzied period of youthful experiment, marked by rapid editing and close-ups, Dreyer's experimentation took a different turn, towards gliding tracking shots and the long take, simply because he slowed down with age.

The slowing down is certainly marked: there are over 1500 shots in 82 minutes in The Passion of Joan of Arc; just 114 shots in 126 minutes in Ordet. Consider Dryer's three late masterpieces: Day of Wrath took twelve days to edit, Ordet took five, Gertrud just three. As David Bordwell notes in Figures Traced in Light, the average shot length in Day of Wrath was fifteen seconds, in Ordet it was sixty-five seconds, in Getrud it was ninety seconds. Elsewhere, David Bordwell notes that Dreyer, Chaplin and Gance were all born in 1889, and that a generation of young directors embarked on energetic experiment at the same time. He argues that "youth matters" in cinema. Fast forward from the 1920s to the 1960s; substitute Bertolucci, Truffaut, and Godard for Chaplin, Dreyer, and Gance; et voila, the same dynamics are at play: febrile energy, experimental daring, excited cinephilia and the exchange of ideas. In Paris, Palma, and Rome young directors, using young actors to make films for young audiences, were experimenting as their forebears did. Emmanuel Laurent's documentary about the French New Wave, Deux de la vague/Two in the Wave (2010), contains extracts from a conversation between Fritz Lang and Godard, filmed in the early 60s. The young Godard groups Lang with Gance and Renoir. He says that what strikes him about those older directors is their eternal youth and their interest in things as they're born, in new (cinematic) problems. Lang interrupts him and says: "Listen, our métier, the art of cinema, isn't just the art of our century, it's also the art of youth." Godard, unsurprisingly, is quick to agree. A sense of mutual respect existed between Dreyer, Gance, Lang, Renoir – that older generation of directors – and the Young Turks of the New Wave. It amounted to a series of father-son relationships within the family of cinema. More precisely, it was a series of surrogate father-son relationships, as the experienced masters often replaced absent or actual fathers.

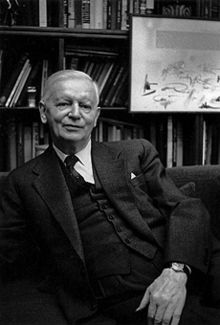

When Danish documentary filmmaker Jørgen Roos asked Dreyer if he could make a film about him, Dreyer replied: "But why would you make a film about me? I'm not of interest, but my films are." A deeper knowledge of Dreyer's personal life, influences, and motivations edges us closer to an understanding of his occasionally cryptic work, but, as lb Monty says in his note on his old friend for the Film Directors Site, Dreyer's personality was expressed clearly and graphically in the films themselves. His development as a director and an individual are, of course, intimately connected, if not inextricably so. Dreyer recognised this himself. In his 1943 essay, A Little on Film Style, he says: "The soul is shown through style, which is the artist's way of giving expression to this perception of his material."

Ultimately, what matters with Dreyer is not youth, or mothers and fathers, or the lack of them, or Falconetti's face, but the images arising from his endless search for new forms of cinematic expression. Dreyer continued to experiment in his old age, just as Godard, Rossellini, and Welles did. After the advent of sound, for instance, Dreyer's work becomes increasingly painterly. If the influence of Braque and Wyndham Lewis is evident in The Passion of Joan of Arc, and that of Munch and Whistler in Vampyr, it is as nothing to the debt Day of Wrath owes to Rembrandt, that Ordet owes to Vermeer, or Gertrud to Hammershøi. Paradoxically, the influence of great Nordic writers like Kaj Munk, Jens Peter Jacobsen, Hjalmar Söderberg, and Haldór Laxness becomes also more marked as he experimented with new ways of composing images. Dreyer experimented with sound too: the muffled voices and animal noises of Vampyr are like nothing else in cinema, it is the relentless ringing of the witch bell that establishes the fear-drenched mood of Day of Wrath, it is Poul Schierbeck's lilting melodies that create the melancholy mood of Ordet. Sadly, he was never to experiment with colour, as he'd hoped to with Gertrud.

The further into the sound period Dreyer moved, though, the more pronounced became the sense of silence in his films. Dreyer seemed to want to return to his youth, to first principles, and to images; to the moment cinema and psychoanalysis were born together. Despite what appears to be the increased 'theatricalization' of his final films, they not only seemed more painterly, but also more meditative and still. If The Passion of Joan of Arc is a silent film that seems to speak, Vampyr is a sound film that craves silence, while Getrud feels the need to speak but talks to us more eloquently because of its pauses and silences. In his later masterpieces, Dreyer, along with Antonioni, practically invented 'slow cinema': a form that thinks and allows thought the time to form; a contemplative cinema that details 'dead time'; a cinema that recognizes the thoughtful silences, suppressed emotions, distracting memories, and, even, the occasional moments of boredom that are a part of human interaction and communication. Silence seemed to re-enter cinema at this point, along with a slower – sometimes jerky, sometimes languid – kind of movement. Dreyer, as surely as Antonioni, marked the moment the talkies became the walkies.

| Exercises In Paying Attention |

|

As I write these final thoughts, BBC Radio 4 murmurs peacefully in the background. I'm half listening to an amusing, if annoying programme in which a panel are chattering away about ways the market might save us from environmental catastrophe. Suddenly, one of the guests says something that distracts me. My ears prick up. Author, environmentalist, and Old Etonian William Fiennes has just turned a neat phrase that sums up Dreyer's films for me: "exercises in paying attention." Dryer's last five feature films were touched by genius, but even the minor films reflect Dreyer's painstaking, loving attention to detail and to people. We attend more closely to those and that which we love. Dreyer's every exercise in paying attention reflected his love of cinema, his one great passion.

Nations have a childlike need for comforting bedtime stories and consoling myths; they need their unifying, binding political and cultural legends. Denmark is as lucky to have Grundtvig and Dreyer, as France is fortunate to have Joan of Arc and Godard. All four, in their different ways, spoke truth to power. All four stand as symbols of tolerance and unsullied integrity, of childlike innocence and the resoluteness of innocence. Faith, albeit in different forms, is the light that guided all their choices. Like Godard, Dreyer placed his faith in cinema. Like Godard, Dreyer embraced cinema as a religion, a calling, and a guiding passion. But Dreyer was his own man, with his own demons and his own inimitable style. It is, of course, a tragedy that he made so few films, but each exquisite film he left us declares his life well lived and his prodigious talents well used. Dreyer's passion and soul warm us still. They echo in films as various as Gabriel Axel's Babette's Feast, Michael Haneke's The White Ribbon, Thomas Vinterberg's The Hunt, and in a thousand others. As Andrew Sarris once said: "Dreyer simply isn't cinema. Cinema is Dreyer."

<previous | next>

Part 1 | Part 2 | Blu-ray details

|