| |

"I introduced myself and told him that I adored his movies, his contributions to film, because he was the first guy who really started making films about the reality of the vacuity between people, the difficulty in traversing this space between lovers in modern day ... and he never gives you an answer, Antonioni – that's the beautiful thing." |

| |

Actor, Peter Weller |

"The reality of the vacuity between people..."

It's a fascinating subject, to be sure. Not so sure it's going to compete with Tony Stark's Hulkbuster suit for broad cinematic appeal but nor should it. As far as we travel into the billion-dollar box office stratosphere, the harder it is to return to defiantly artistic subjects and make them a vital and viable genre of modern cinema. Or as Steve Utley, the Odeon cinema manager in the late 70s and 80s and my once-boss might have said about an 'artistic' film, "It won't take a light..." That's as maybe but Antonioni's voice is just as vital and relevant even if he made films that relatively smaller audiences would chose to see. There are few true artists in cinema and fewer self-proclaimed artists but of all the John Fords, the Orson Welleses and the Ingmar Bergmans of this world - and of those acclaimed as more than mere film directors - Michelangelo Antonioni's light burns brightly. In some ways he's the Italian anti-director with little interest in what drives the mainstream cinema based squarely on 'inciting incidents' and the three-act structure. The plots of his English speaking films (I have not seen his Italian work, more on that lapse in the next paragraph) are meandering and resist dramatic tension intentionally. Antonioni's passion seems to be situated in and based on what's between the lines of an ordinary narrative. Paraphrasing from Ephraim Katz's seminal Film Encyclopaedia, the cinema of Antonioni features modern man seemingly ill suited to the world of his own making and finding relationships and communication difficult. Even the mystery of his own emotional state is utterly beyond his comprehension. This outlook or directorial ambition produces cinema at a significant variance to what most would define as cinema, works that that defy conventional analysis and appreciation. I'm not going to reduce it to metaphorical Marmite, however tempting, but I think you have to have a predilection for challenging work to truly soak up an Antonioni picture. I confess a rampant curiosity but if you are looking for comment from someone who truly gets this man's cinematic world view (like Jack Nicholson for one) then you'll just have to be satisfied with my relatively tangential take on The Passenger. But then after four viewings (there are three commentary tracks!) I may have found my own way in.

There are several filmmakers and titles on a cinephile's list that she/he would be embarrassed to admit they'd never sampled. "Call yourself a fan of cinema and you've not seen a film by (fill in famous filmmaker here)?" There are a few no-show skeletons in my particular closet but life is a finite resource and there are always many things going on to drain any free time I might have been able to set aside for cinematic education. One on my list got ticked a few years ago, Antonioni's Zabriskie Point, which if you've seen it, should convince you that the director is less interested in creating box office smashes than he is making art. Art and commerce cosied up to each other with his first English speaking effort, the terrific Blow Up. His 'swinging London' mystery made more than ten times it cost but it may have set an awkward precedent. Zabriskie Point lost a fortune and The Passenger didn't fare much better but hey, this is what happens when you get artists to make movies. You get art. Hollywood thinking is always the same... "This guy made a movie for 'x' and it made 10'x'. Give him more money!" Once more, there's that executive trap waiting to snare the pre-conditioned; filmmakers do not make hit movies. Audiences do.

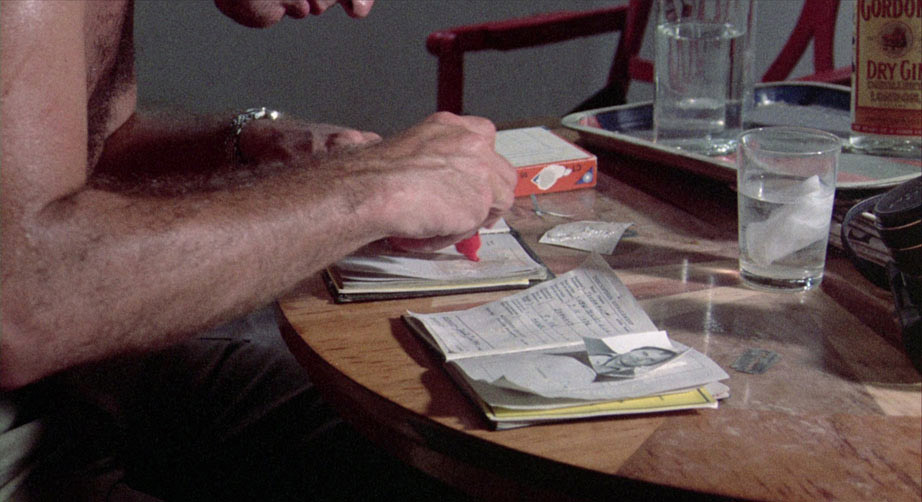

So here's a parallel analogy for the intriguing premise at the heart of The Passenger, an analogy that's the basis of one of my own screenplays... You just got off a plane. Your life is aimless and undefined. You leave your luggage on the carousel. You are in an existential crisis. As you leave customs, you see a hundred or so men and women holding up placards with unfamiliar names on then. Pick one. Start a new life... Given the relative unimportance of the narrative to an artist like Antonioni, a synopsis seems unhelpful but it may frame the movie enough to pique your interest. Now this paragraph has no spoilers but it does have information that the film does not supply all at once. You may want to go in cold. You have no idea, at first, what the lead character does or is doing in the desert but you just accept events as they take place but officially, David Locke (Jack Nicholson) is a television reporter hoping for a story or interview on gun running in the African desert. He tries to find his way with no real contacts but ends up frustrated and stranded, his Landrover stuck deep in the sand. Returning to his bare, basic hotel room in the stark heat, he finds his neighbour Robertson, now a corpse with a fine resemblance to Nicholson. In no time, passports are forged and to escape his banal existence, Locke becomes Robertson. In terms of good ideas? Not one of his best. He manages to free himself from existential handcuffs while simultaneously locking himself in a cell.

The problem here, or dramatic irony as it's known in the trade, is that Locke has gone from merely courting danger in his role of a professional journalist to embedding himself in a world even less forgiving. Alive, Robertson was an arms dealer and to Locke's credit, he jumps in with both feet and plays the part seeing where it takes him. Again I am reminded of André Gregory's quote over dinner with Wallace Shawn... "Things don't affect people the way they used to. I mean it may very well be that 10 years from now people will pay $10,000 in cash to be castrated just in order to be affected by something." Well, a tad drastic perhaps but in so many ways, this is what Locke is doing, locking and loading himself into someone else's breach and seeing what he's fired at. Along the way, through a series of coincidences, ones that you never really question, he hooks up with architecture student 'girl', played disarmingly by Maria Schneider. There's a timely point to be made that both lead females in the comparable Two Lane Blacktop and The Passenger are both unnamed 'girl's. Not sure what that point would be but it's probably tangentially related to this global hyper-awareness of how men have had things their own way for a long, long time. Vive la change. In fact, dwelling on the characters a little more deeply and you find that there is a lot of Albert Camus' L'Étranger in Nicholson's Locke, both characters drifting on the tides of absurdity and buffeted by people and events far from their singular experience of being alive (see the booklet paragraph for more on this). Once tucked in to his new life, Locke wanders the world where Robertson's little notebook guides him, his fate slowly narrowing courtesy of an indefatigable narrative noose ever tightening.

Because of Antonioni's staunchly Brechtian reserve, and his never giving in to conventional cinematic emotional arousal, it is the hardest thing in his cinematic world (for me) to really care about anyone. But is this like saying that I am frustrated by not getting a jackpot from a one-armed bandit when I don't get a winning line? How does one attempt to care amidst such total detachment? But is this is to miss the point of Antonioni's work? Two bells and a bunch of grapes? At this early stage in his career, Nicholson wasn't 'Jack' but a star in the making with a talent that became subsumed by his own 'Jack'-ness. It's hard to imagine a more charismatic performer and together with Maria Schneider they make a great couple but do we care? Are we even supposed to care? Hell, if you see Zabriskie Point, you should at least be prepared for a very different experience in the dark in more ways than one. There's no question that Antonioni has his unique style. And I'm all for subtle and broad gradations in film directors' different interpretations but it is a hard style to champion after so many years of cinema behaving itself and allowing us to care for characters rather than just observe them moving through spaces. Yes, I am aware of how naïve that view may be, restricting cinema to such narrow confines. Narrow they may be but those emotional imperatives find themselves in ninety-five per cent of cinema that I am aware of. After Mark Cousin's wrist slap about the genre of 'musicals' in this month's Sight and Sound, I am feeling even more unqualified to speak about these things with any authority but I will argue vociferously that Cabaret is NOT a 'musical'. I digress.

Inevitably, there are moments in the film that invite some comment. Twenty-two years before Jack (Dawson) leans over the front rail of the Titanic in that movie whose title escapes me for the moment, another Jack (Nicholson) makes the same physical move over water in a Spanish cable car about fifty-four minutes in. It's a very cinematic gesture so of course, it's completely out of place in The Passenger. It happens a second time but ever so briefly but this time with Schneider in a convertible. Many of the shots are not faultless in terms of camera operation. Now I highly doubt that Antonioni instructed his operator to jiggle slightly on camera moves but there is a rough and ready aspect to the coverage that is very noticeable. Despite all the fuss over the extraordinary penultimate shot, its status as a classic surely must have been dented in light of today's technology? The shot is a six and a half minute, cripplingly slow track through a metal railing at a window followed by a track through a courtyard and then rounds in a circle to come back and look through the window from the other side. It is far from technically perfect but it must have been groundbreaking at the time. In the Jenny Runacre and the stills extras there's a still of the rig and it's impressive. The only real give away is that the railings which were obviously pulled apart to let the camera get through, aren't moved apart in sync so rather than the effect of a slow dolly in, we are treated to the results of two technicians trying to time the physical rail movement of parting pieces. It's not hugely convincing. In fact, its self-consciousness works against it in the same way that CGI affects an honest emotional response today. As soon as the shot starts to assert its own importance by being long, slow and continuous, I find myself thinking about the shot in the way I never thought about Welles' magnificent opening shot of Touch of Evil. It's all the difference in the world between involvement and detachment. Welcome to the world of Michelangelo Antonioni.

Presented in the 1.85:1 aspect ratio, the film itself looks terrific. 70s film stock has a special place in my heart and the endemic grain is rarely distracting. The exotic locations and their enticing climates ensure that the stock is given the very best treatment. The contrast levels are pleasing and of all the countries featured in the film, England seems to have been shot in the least flattering literal light but that's because it's up against some stiff and striking competition. Colours are naturalistic and the colour timing reproduces the reality of the scenes.

The original mono soundtrack is clear and largely free from hiss and there are new and improved English subtitles for the deaf and hard-of-hearing.

Alternative presentation with original Italian Professione: Reporter titles and credits

A first! For me at least. This is simply the front and end credits in Italian. I'm not sure anything else I say on this extra will be useful at this point.

Audio commentary with actor Jack Nicholson (2006)

One of two commentaries ported over from the 2006 DVD release of the movie, is sepulchral of voice, star Jack Nicholson. His delivery is such that it's often difficult to catch entire sentences. He was 68 in 2006 and his voice, though unmistakably 'Jack' has the slower and lower pitch delivery of an older man. It's heartening to know that Nicholson is well aware what kind of filmmaker Antonioni is and how hard his films may be to read and their slowness of pace may not sit well with the computer game generation. He talks about the film's rhythms and how recorded on location sound has a reality to it. There's a lovely story about there being a bright pink plane at an airport location and how the crew worked to obscure it in case some critic accused the director of having the plane painted pink for his own artistic reasons. The pink plane is still in the picture.

In a very odd scene in the film, a white guy Kung Fu kicks a black guy which prompts Nicholson to say "Random thug," for reasons beyond me. He says that "I'm not as funny doing an Antonioni picture, huh?" There's the story of how the crew once moved locations and left the director behind by mistake. He confided in Nicholson that he was supposed to be furious but wasn't at all but had to keep up the pretence. The painting of the oranges is discussed and the fact that Nicholson was asleep in this scene. When director and star are having an argument about which way to go, Nicholson as commentator says "Hmmm." He really gets his director! Inevitably, the end shot is dissected and to the question, "Why did you do all this?", Antonioni apparently answered "I just didn't want to film a death scene!" At the tail of the commentary, Nicholson simply says "It's great!" and it's clear the star 'gets' the Italian maestro's intentions more than myself (at first).

Audio commentary with screenwriter Mark Peploe and journalist Aurora Irvine (2006)

The second port from the 2006 DVD is this commentary track. Aurora Irvine recently saw the film for the first time and the few moments she chimes in to add or ask questions of the co-screenwriter prompts a series of different responses. There is a tiny sense of defensiveness from Peploe in some of his answers, something that is unsurprising speaking in 2006 about a work made in 1975 when attitudes were very different and I do sympathise. His wife at the time was the costume designer and so scattered in throughout the commentary are lines like "That's my shirt!" and "My daughter still has Maria's eagle blouse..."

They talk about the irony inherent in the structure of the film and the portent of the date of Locke's death, interestingly, it's the 11th September. I didn't mention it in the review but there is a real execution in the middle of the film, footage that Antonioni is secretive about having sourced. Peploe is obviously uneasy about this material and it's still painful for him to see it included in the picture. Peploe mentions that the characters' names have relevance and then says no more on the subject. He clearly has a soft spot for Schneider who could do no wrong and is a natural born talent. Her documentary-like performance was what made her compelling. There's the lovely idea that a car windshield is like a movie screen and a wonderful aural typo when he's talking about the Spanish location Almeira doubling for the wild west where Sergio Leone shot his Spaghetti westerns, for example, Peploe says, The Good, the Bad and the Beautiful... Now there's a Leone movie I'd like to see but he's probably already made it under the title Once Upon A Time In The West. He talks about the famous Zabriskie Point explosion covered by fifteen cameras and his respect for Antonioni himself saying that "Antonioni would never give up, a great man..."

New audio commentary with film historian Adrian Martin (2018)

Martin asks us to imagine we're seeing the film for the first time. He's going to analyse the narrative rather than provide production information which is OK by me. Antonioni plunges you into the situation and you know very little. Narrative aspects that 'float' are incredibly important to the filmmaker. Antonioni sees instability as productive – new shapes and stories come into existence. This academic reading of the film complements the other two commentaries very well. Martin mentions the lovely inversion of the racist cliché that white people cannot tell black people apart and there's a small blip when Martin talks about Cary Grant in North by Northwest having to act as Roger Thornhill. He is Roger Thornhill. It's fictitious agent George Kaplan he has to pretend to be.

This is a very useful commentary with a moment of irony that I can't pass up. As Martin reveals that Locke and the girl hardly ever touch in the movie, Nicholson's hand touches Schneider's back and then they link up physically as a couple, touching backsides as they walk into a restaurant. It has to be the worst commentary timing to make that otherwise useful point about physical intimacy between the two. French philosopher Roland Barthes, gave us three words to describe the art of Antonioni and I find myself in some agreement... Vigilance, wisdom and fragility. My avatar of the man is now one of a crystal owl...

Jenny Runacre on The Passenger: new interview in which the South African-born English actor recalls the film's production (2018, 14' 21")

This is a lovely reminiscence with Runcorn whose stories are enlightening and entertaining. Antonioni had seen Husbands directed by John Cassavetes and simply had cast her from a distance. "The film is a study of alienation..." We get another perspective on the penultimate shot and her interview ends with a rueful laugh on the nature of fame.

Steven Berkoff on The Passenger: new interview in which the actor-writer-director remembers working with Antonioni (2018, 10' 12")

Some lovely stories from the older Berkoff with his cat briefly taking centre stage. It's striking how Daniel Craig-ish the younger Berkoff was; bluff, dangerous, dark and compelling. He talks about recognising a 'master', traits like extreme casualness, very calm, very easy. Master filmmakers are also concerned with the actors. He brings up Kubrick with whom he worked twice and also comments on The Passenger's commercial failure.

Profession Reporter: Michelangelo Antonioni discusses The Passenger in an archival interview conducted at the 1975 Cannes Film Festival (1975, 4' 53")

Antonioni muses on the colour in the film, the profession of reporter and bats back a statement from the interviewer that the "feelings we get from the film are boredom and passivity." I have to say I felt that was fair from a certain point of view. It's all about how you see and interpret what you are watching and a lot of us don't have the sensitivity or the training to take in films like this without some initial reluctance and pre-training. The director is once again asked about his penultimate shot.

Antonioni on Cinema: the acclaimed filmmaker discusses The Passenger and his philosophy of cinema (1975, 4' 39")

A short hotel interview where the great man expresses great surprise if any of his films become hits! You have to hand it to the man. He knows his art's limitations. His opinions about the intelligence of actors is revealing (and I think he's right) but he wouldn't be tempted to reveal the identities of those less-intelligent actors who were capable of delivering an extraordinary performance.

The Final Sequence: Antonioni analyses The Passenger's much-celebrated climactic sequence(1985, 12' 37")

For completists, the director takes us through the final shot stopping in the cutting room when needing to explain things. I have a strong romantic attachment to the sound of film kit pushing frames through gates. It looked like a flat bed Steenbeck but the controller was different... A KEM perhaps? Ah, I can smell the celluloid.

Original theatrical trailer (2' 03")

"A spellbinding journey into identity..." If this is indeed the original theatrical trailer, why does it proclaim that 'the lost 1975 classic is back'? Where had it been? Oh, MGM's publicity people have been to marketing school. There's a handgun found in Robertson's belongings and it's one shot. The gun is handled briefly by Schneider but in the trailer, its promise is far more potent. There is 70s thriller music here that is so out of place once you've seen the film itself, it's almost laughable. All the few action beats are milked for all their worth. And I do believe there's a typo in the director's name (that had to be an 'ouch,'). According to most sources including the movie itself, it's Michelangelo. In screaming red letters at the tail of the trailer, he's credited as 'Michaelangelo' while his three further credits at the end titles are all correct. As I said, "Ouch!"

Image gallery: on-set and promotional photography

This feature includes twenty-three colour images of behind the scenes shots, twenty-four including a few doubles of black and white shots and nine posters, different designs and international versions.

Limited edition exclusive 40-page booklet with a new essay by Amy Simmons, Antonioni's production notes, archival interviews with Antonioni and Nicholson, and film credits

As usual, a terrific accompaniment to the disc, the booklet helps as a primer for the cinema of Antonioni. Amy Simmons' modern look back credits The Passenger as a 'languidly beautiful masterwork.' She goes on to back up her view with great insight and many examples of what drives Antonioni. What slightly puzzles me in terms of the great regard in which he is held, is that almost everything that the director does in terms of detachment and style is a sort of anti-cinema. If he were entrusted to shoot a one hundred metres sprint, no one would leave the starting blocks. He actively resists cinematic tropes and while that makes him interesting, it also puts up more than one barrier to get an emotional response from an audience. In terms of appreciation, I find myself half at sea and half on shore. Antonioni's two-page extract from the original production notes sets up his credentials as the film director as artist. The interview with the man reveals a few gems about his view of the film but one particular answer to a question (about the significance of shooting the oddly shaped Gaudí buildings of the Spanish locations) typifies what drives me crazy about a certain kind of thinking or interpretation. Antonioni's answer? "The Gaudí towers reveal, perhaps, the oddity of an encounter between a man who has the name of a dead man and a girl who doesn't have any name." I mean, that's just mad, Ted. Isn't that taking artistic interpretation a little far? Dare I utter the 'P' word?

Bollocks. The booklet just brought up Camus, something I read twenty minutes after the insight had occurred to me in the review. You'll just have to trust me on this but writing for Outsider, this is a common occupational hazard. The last but one section in the booklet is another interview extracted from a 1975 Film Comment. It makes me smile that not only does Antonioni mention that the comparison with Camus has been brought up before, he also pooh poohs it soundly. In the notes at the end of this piece, a common misconception is hammered home, the idea that Mersault (L'Étranger's protagonist) was indifferent to his mother's death. I've gone into this in more detail in the second paragraph of my review of Arrival here. Jack Nicholson weighs in with a short piece on the film taken from a 1974 Sight and Sound interview, saying in his own inimitable way that the success of Blow Up was probably because, and I quote, "...it included the first beaver shot in a conventional theatre." Nicholson's analysis is probably true. So much for art.

At first impenetrable and frankly exquisitely frustrating, The Passenger eschews any conventional cinematic form and just presents itself with a defiance that manages to conceal some of its more artistic conceits. There's no doubt in my mind that Antonioni is an acquired taste and after four viewings I began to grasp the hem of the garment so roundly praised by other more informed commentators. I'm not a convert (well, not yet) but I am thrilled that artistic cinema is being given such a solid platform. And Indicator has done the film proud.

|