|

Don’t you love it when a film hooks you in its opening minutes by keeping you in the dark about exactly what is going on? If you do, and if you’ve so far read nothing about the 1949 Obsession (aka The Hidden Room), then you might want to skip forward to the technical specs or stop reading now and get your hands on this disc. Take it from me, if you have a soft spot for darkly themed, noirish British thrillers of the 1940s and 50s, you should have a ball with this one. For those prepared to stay with me, perhaps because they’ve already encountered a plot synopsis, have seen the film already, or even simply want to know more before deciding whether this film is for them, consider this reaction from someone who went into it completely cold.

It opens in London one night in one of those ghastly clubs that forbade entry to women, as four well-to-do men sit around talking colonial piffle. Well three of them do. The fourth, eminent psychiatrist Dr. Clive Riordan (Robert Newton), seems preoccupied with the time and more than a little anxious about the pocket of one of the overcoats hanging in the cloakroom. When another club member approaches the stored coats, Clive has a brief anxious moment as the overcoat he has been nervously eyeing is taken off of its hook, only to see to his relief that the coat the man was looking for was on the same peg beneath it. What, I began to wonder, is going on here? Eventually, Clive makes his excuses and departs, reassuringly checking his overcoat pocket as he leaves and hailing a cab to Church Row in Hamstead. When he reaches his destination, he cautiously walks down the silent and empty street whilst apprehensively eyeing up a particular house on the other side of the road. After pausing for a moment, he approaches it and makes moves to knock on the door before spotting the doorbell, which he gives a solid tug. He’s about to ring it a second time when he hears a vehicle approaching, and instead nips into the nearby shadows until it passes. Seriously, what the Sam Hill is going on here?

The mystery continues when the door is answered by an elderly man named Aitkin (James Harcourt) in his dressing gown, who greets Clive with a most unexpected, “Oh, it’s you, sir!” as Clive strides in past him like he owns the place. As it turns out, he does, and it’s quickly established that he’s been away on holiday in Torquay and that Aitkin wasn’t expecting him home for another two weeks. When Clive replies that Torquay has been postponed because of an urgent case, Aikin responds by repeating his original enquiry verbatim, and in what at first seems just like a nice little bit of business, Clive switches on Aikin’s hearing aid and restates his response, and in a manner that suggests this is a frequent occurrence in the Riordan household. My curiosity about the contents of that overcoat pocket piqued again when Clive sharply declines Aitkin’s offer to take it from him, claiming that he wants to keep it on for now because he’s feeling a little chilly. After enquiring if his wife had a caller that evening – no, he is told, she left alone in a taxi – Clive tells Aitkin he can go back to bed and that he will wait up to greet his wife when she returns. Once Aitkin has departed, Clive takes that damned coat off and hangs it in the closet, then turns off the lights and checks on the sound of a passing vehicle outside. He then returns to the closet and finally retrieves the object that he’s spent all evening being so anxious about. It’s a gun. Suddenly, everything starts clicking into place – his nervousness at the idea that someone might accidentally discover what was in his coat pocket, his wife out for the evening under the impression that he is still in Torquay and due home soon, a butler whom we now know can’t hear a thing without the assistance of a hearing aid that he keeps forgetting to switch on. Murder is clearly in the air. But why?

We soon find out when a car pulls up outside, prompting Clive to secrete himself behind a curtain. The front door then opens and his wife Storm (Dally Gray) enters in the company of good looking young American Bill Kronin (Phil Brown), with whom she is clearly having an affair. Clive stays hidden for long enough for the couple to metaphorically hang themselves, then waltzes out calmly from his place of hiding and politely confronts them. The dynamic of the scene that follows could be the subject of a small essay in itself, in particular how indignantly Storm (great name, by the way) responds to Clive’s threats and wily bluff-calling after the adulterous couple attempt to spin alternate yarns about why they are together this evening. Only when Clive fires a warning shot from his gun into the doorframe close to both of their heads does it dawn on the couple that there may be substance to his claim that he intends to kill them. He’s clearly thought this through and has all the bases covered, even allowing Storm to at one point to snatch the gun and attempt to shoot him, having secretly removed the magazine from the weapon first. Finally, Storm lives up to her name by angrily leaving the room and marching upstairs to bed. Surprisingly, Clive makes no move to stop her, instead turning his attention to the now deeply concerned Bill, who questions whether Clive would really kill him over “a harmless little flirtation.” Clive responds by revealing that there have been so many such harmless little flirtations. “You’ve heard of the last straw, haven’t you, Bill?” he asks. “Well, you’re it.” With that, he leads Clive out of the house at gunpoint, their departure observed from behind nearby iron railings in a slowly panning wide shot that comes to rest on a large and prominently foregrounded gravestone, behind which the two figures then symbolically disappear. Ominously dark stuff to be sure, but both Clive and the film are just getting started here, so once again, if you’d rather learn no more about what subsequently unfolds, hop to the final paragraph, or click here to do so automatically.

We then skip forward a few days, and what happened to Bill is left teasingly unexplained. Clive is back at his club listening to his friends waffle on and at work in his practice, and he and Storm are once again behaving like the tetchy couple they presumably were in the lead up to that fateful night. As Clive sees his last patient for the day and sends his receptionist Miss Stevens (Betty Cooper) home, he is visited by Storm, who claims to have received a letter from Bill telling her he loves her and is waiting for her, but it’s clear from Clive’s reaction that he knows that she’s spinning a yarn, probably to push him into revealing whether Bill is alive or dead. When Storm leaves in a fury, Clive nips into a side room that he has transformed into a moodily lit chemistry lab. We then watch in real time as he silently dons a protective apron and gloves and adds several spoons of a powder to a beaker that he connects to one containing a boiling liquid, then drains the contents of another into a rubber hot water bottle. After pouring the first, now darkened chemical into a thermos flask, he packs that and the hot water bottle into a medical bag and departs. Once again, I found myself wondering what exactly was going on here. I didn’t have to wait long to find out.

After leaving his office, Clive heads to the nearby garage in which he stores his car while at work, but instead of entering the vehicle and heading home, he exits through the rear door and past the ruins of a bombed out house, then descends a strip of wasteland and enters a small tunnel. Inside this is a door that opens onto a dark and narrow passageway that leads to an underground room, inside which Bill is lounging on a bed and very much alive. Again the film toys with the audience, as the two men chat almost amiably about which page of the newspaper the story of Bill’s disappearance is on today, the initial suggestion being that Bill has agreed to cooperate in a plot that requires him to remain in hiding for a while. We’re a couple of minutes into the scene before it’s clearly revealed (keep your eye on the background and you'll suss this earlier) that Bill’s ankle is secured by a heavy chain to the wall, restricting him to a portion of the room marked out by a white painted circle on the floor that Clive makes sure not to enter. As the two men continue to converse, Clive takes the contents of the water bottle and pours them into a bath in a side room that is just out of Bill’s view and reach and leaves food and the flask we saw him filling earlier on the rim of the painted circle. In a neat piece of black humour, it’s revealed that the chemical that Clive was boiling up in the first beaker on his chemical bench was nothing more sinister than a flask of coffee for his prisoner. The hot water bottle is a different story, and you won’t need a degree in criminology to have worked out by this point that it contains an acid in which Clive plans to dissolve the presumably dead Clive’s body. Indeed, Clive repeatedly makes it clear to Bill that that he still intends to kill him when the time is right. The question is why, if he means what he says, is he keeping him alive for an undetermined period, and exactly when and how will he commit the terrible deed?

The script for Obsession, which is a better title than the more prosaic American alternative, The Hidden Room, was adapted by Alec Coppel from his 1947 novel, A Man About a Dog (which, for reasons I’ve elected not to even hint at here, is an even better title), and directed by acclaimed Canadian-American filmmaker Edward Dmytryk, one of the famed Hollywood Ten writers and directors who were blacklisted for refusing to testify to the House Un-American Activities Committee. It’s been convincingly argued elsewhere that Dmytryk brings a 40s Hollywood noir aesthetic to this darkly toned crime story, and it proves to be a multicultural marriage made in a darkly twisted heaven, one filled with ominous shadows and malicious intent. Indeed, although the victim here is also an American émigré (as was the blacklisted actor who plays him), what struck me most about Obsession is how quintessentially English it is, all polite conversations, carefully chosen words and calm matter-of-factness, with potentially lethal threats delivered with all the emotional detachment of a casual workplace chat about a paper clip consignment. Unexpectedly, this somehow makes Clive’s subsequent actions and behaviour feel even nastier and more coldly calculated, and the resulting threat to Bill’s life all the more palpable. Then, at almost exactly the halfway mark, this dark tone is unexpected lightened a little by the arrival on the scene of Superintendent Finsbury (Naunton Wayne), the Scotland Yard detective assigned to investigate Bill’s disappearance. Entering Clive’s office on the tail of a puff of pipe smoke, he’s the epitome of politely genteel Englishness, but in a move that became a signature of TV’s Lieutenant Columbo, is able to get under the otherwise unflappable Clive’s skin simply by turning up unexpectedly at various locations with just one more question about the case.

Given the limited locations and importance of dialogue in the development of both the characters and plot, I wasn’t completely surprised to discover that Coppel’s source novel had already been adapted as a stage play, but Dmytryk’s direction, in conjunction with cinematographer C.M. Pennington-Richards’ moodily atmospheric use of light and shadow, brings a cinematic flair to what so easily could have been a visually pedestrian piece of filmed theatre. His influence is first evident in the opening scene, when Clive’s concern about the contents of his overcoat pocket is wordlessly communicated by the camera dollying smoothly right up to the pocket in question. This expressive use of camera crops up again later, when Clive is curiously trying to work out how Finsbury could have so quickly found the bullet that he fired as a warning shot into the door frame, despite his seemingly successful attempt to cover it up. As he fixes his eyeline on the spot in question and walks towards and away from it to assess its visibility, the camera adopts his viewpoint and glides in and out with him in a manner that allows us to realise that the spot is cloaked almost invisibly in shadow without this fact having to be verbally confirmed.

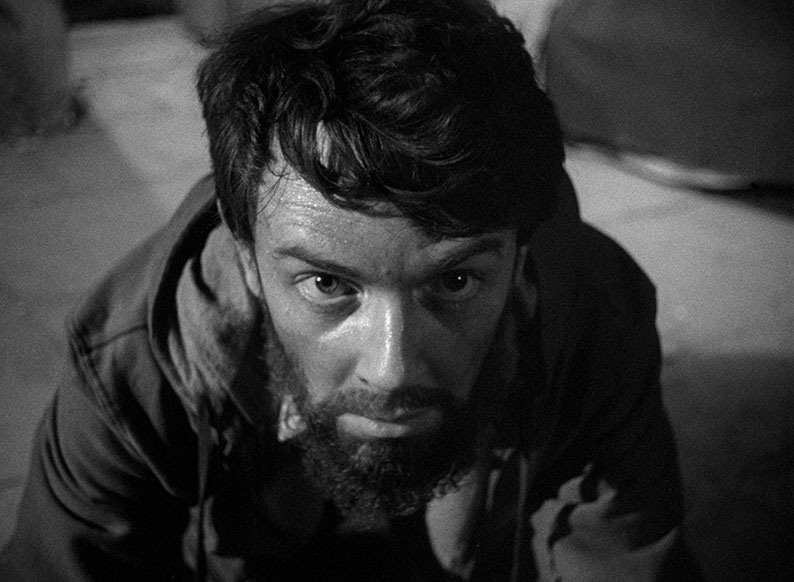

But the real strength of Dymtryk’s approach is the trust that he has in Coppel’s smartly written dialogue and his impeccably chosen cast. Robert Newton is too often remembered primarily for his eye-rolling, character-defining portrayal of pirate Long John Silver in Disney’s adaptation of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island (Byron Haskin, 1950). Here, he radiates menace and malicious intent with a subtlety and emotional coldness that not only demonstrates what a fine screen actor he could be with the right role and right director, but this approach also proves more incisively sinister than casting Clive as a more emotional and openly intimidating villain. For him, this is deadly game of his own devising, for which he has drawn up rules that are designed not only to assure that he will win no matter what turn events might take, but also to protect himself if things should go unexpectedly awry. I’ve not yet seen anything like all of Newton’s films, but I’ve no problem stating that his portrayal of Dr. Clive Riordan is my favourite to date, and that includes his superb performance as the brutish Bill Sykes in David Lean’s 1948 exemplary take on Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist (1948). In what gradually develops into the flipside of Clive’s emotional coolness, Phil Brown – best known now for playing Luke Skywalker’s Uncle Owen in the very first Star Wars (1977 – A New Hope my arse) – also shines as the unfortunate Bill. Over the course of the story, Brown expertly charts Bill’s gradual transformation from awkwardly caught-in-the-act adulterer to broken and thick-bearded prisoner desperately grasping at anything that might delay his seemingly inevitable execution, or even prompt his vengeful tormentor to have a change of heart. Intermittently lifting the mood as Superintendent Finsbury is Naughton Wayne, who is probably still best known for his engaging double act as Caldicott to Basil Radford’s Charters over the course of four films starting in 1938 with Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes (the two also played rivals in love in the only comic story in the brilliant 1954 portmanteau horror Dead of Night, and were regularly partnered in later films). Unsurprisingly, perhaps, he brings the quaint middle-class Englishness of Caldicott to his performance here, which makes him a near-perfect foil for the carefully cultured Clive. And then there’s Sally Gray, who takes no prisoners as Storm and proves to be a fiery example of nominative determinism of character in her refusal to be intimidated by Clive, even when he’s pointing a gun in her direction and threatening to kill her. Quite what brought these two mismatched individuals together in the first place and what has happened since to bring them to this point remains teasingly unclear, but we’re left in no doubt that Storm is a serial philanderer, a point emphasised by an ending (now really is the time to hop to the final paragraph to avoid further spoilers) that sidesteps the imposed moral code of the day by suggesting that, despite all that her affair with Bill has led to, she clearly has no intention of changing her ways.

Where the film really earns its noir credentials is in Clive’s underground imprisonment and psychological torture of the unfortunate Bill, who quickly becomes the prime focus of audience sympathy as a result. Long before the potentially fatal moment arrives, Clive elects to tell Bill why he’s keeping him alive, and confirms that he is slowly filling the bath in the back room with a corrosive acid capable of dissolving all human tissue and bone. Every time that Clive makes his daily visit to the dungeon, Bill is thus faced with the sight of his captor adding more acid to a bath that will be used to wipe all trace of him from existence. This subtle but insidious torment reaches a peak when, after four months of captivity and strong hints that the day of his death is fast approaching, Bill angrily demands to know how much time he has left, to which Clive astonishingly responds, “I don’t expect you to believe me, but these last few months have been getting me down almost as much as they have you. I too will be glad when it’s all over.” Oh, you poor sod. What almost sneaks by unnoticed – it’s certainly not commented on in any of the special features on this disc – is that while Bill is losing his rag, Clive is meticulously pinning a sheet of rubber to the surface of a nearby table, on which he clearly plans to dismember Bill’s body after he is dead for easier dissolving in the acid. This is casually confirmed by Clive when the fateful day arrives (“dismemberment is a terribly messy business”), as completes surfacing the table and lays out a selection of surgical instruments on it in readiness for what must follow. Although I have no interview evidence to back this up, I can’t help thinking that one appeal of this story to the then strongly left-leaning Dmytryk was its incisive portrayal of the mental suffering that a wrongly convicted individual must experience when facing execution for a crime they did not commit.

I’ll admit to having never seen Obsession before this Indicator Blu-ray landed on my doormat, and that I was intrigued from the off by its title, one it shares with several later features and series, including one of Brian De Palma’s most accomplished and directly Hitchcock-influenced works. I was utterly riveted by the film that unfolded, to the point where I was almost yelling at Superintendent Finsbury to get off his oh-so-English arse and do something NOW as the genuinely tense final scenes played out. It’s an impeccably written, directed, photographed and performed slice of British 40s noir that’s as darkly toned and suggestively nasty as they come. If there’s a small weakness, it lies in the discovery that re-ignites Finsbury’s stalled investigation, which relies a little too much on a rather suspect series of chance events. That said, it does give rise to a moment whose 40s innocence has been unfortunately transformed by the ever-evolving nature of language, as one of the dopiest policemen on the force discovers a cat tapped inside an unlocked garage, as says to it, in a voice that almost caused me to spit out my coffee, “There’s a nice pussy!”

The booklet that accompanies this Blu-ray release informs us that Obsession was scanned, restored and colour corrected in 4K at Film Finity in London using 35mm dupe negative film materials, with Phoenix image-processing tools employed to remove many thousands of instances of dirt and eliminate scratches and other imperfections, as well as repair damaged frames. The resulting 1080p transfer, framed in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.37:1, is as impressive as we’ve all come to expect from Indicator, with crisply defined detail, and well-balanced and appropriately punchy contrast with deliciously deep black levels. Film grain is visible throughout and is slightly more prominent on a handful of shots, while a couple of others are a whisper softer on detail, but otherwise the results are top-notch. Dust and damage really do seem to have been banished by the restoration work.

The original mono soundtrack is reproduced here as Linear PCM 1.0 and again is in good shape, the expected restrictions in tonal range not in any way detracting from the clarity of the dialogue and famed Italian composer Nina Rota’s score. The track is also clean, with no obvious signs of wear or damage and little in the way of age-related background hiss.

Optional English subtitles for the hearing impaired have been included.

Audio Commentary with Thirza Wakefield and Melanie Williams

Two-hander commentaries are almost always lively conversational affairs, and this one by researcher Thirza Wakefield and Professor of Film and Television Studies at University of East Anglia, Melanie Williams, is in no danger of busting that trend. Delivering a consistently engaging mix of observation, opinion and background information, the two have some interesting things to say about the characters, the handling, the structure, and the subtext. They note that the landscape, the economy and even the conversations are marked by the war, that the film doesn’t shy away from how horrible and sadistic Clive’s actions are, and reveal that some elements of the plot were so similar to the actions of ‘Acid Bath Murderer’ John George Haigh – whose crimes were committed close to where exterior scenes were shot and who had still not been caught when the film went into production (something the production publicist exploited in a stunt that ultimately backfired) – that the film was refused a certificate by the BBFC, and its release was delayed for several months as a result. They point out that Clive’s ‘weights and measures’ sense of order is in complete opposition to Bill’s more impulsive nature, almost cheer the halfway point arrival of Finsbury and the lighter tone his character brings to otherwise dark proceedings, and even provide an explanation of what they see as the consciously symbolic appearance of white chrysanthemums, something that would otherwise have flown completely over my head. I was given cause to mumble a quiet “dammit” on hearing Superintendent Finsbury compared to TV’s Lieutenant Columbo, but was consoled a little when I realised that Wakefield and Williams’ reasoning for this observation differed to my own. An informative and enjoyable companion to the film.

The John Player Lecture with Edward Dmytryk (73:30)

Conducted at the National Film Theatre in London on 16 April 1972 by film writer John Baxter – whose criminally out of print An Appalling Talent: Ken Russell is one of my very favourite books on films and filmmakers – this audio-only chat with Obsession director Edward Dmytryk is one of the best such onstage conversations that I’ve yet listened to. Dmytryk is an energetic and entertaining speaker with a clear memory of seemingly every detail of just about all of the films he has directed, which gives rise to some really interesting stories about their making, some of which are responses to unusually audible audience questions. He makes his case for why he believes Dick Powell was just right as Philip Marlow in Murder My Sweet (aka Farewell My Lovely, 1944), admits that he’d have preferred not to direct the 1959 remake of The Blue Angel and that his biggest problem there was that he didn’t have Marlene Dietrich, accepts praise for the acting in The Caine Mutiny (1954) but insists it was easy to get a great performance from Humphrey Bogart, and has an amusing story about Gregory Peck wanting more comic dialog in the 1965 Mirage in the hope of emulating the success Cary Grant had with Charade (1963). He responds openly to questions about being blacklisted and moving to the UK, as well as why he later broke rank with the other members of the Hollywood Ten and was able to work once again in America. He also confirms that despite this, he remains strongly left-leaning, noting that the Marxist movement in 30s and 40s American cinema was very healthy, and resulted in filmmakers taking a more honest look at people and society. Seriously, this is just a small sampling from a rich smorgasbord of hugely enjoyable content here.

Richard Dyer: A Man About a Film (34:18)

Academic and author Richard Dyer focuses exclusively on Obsession and those involved its making, describing it up front as the meeting of a very British property and an American director, with the international nature of the project further cemented by the film’s Italian composer. He examines the careers, and specifically the work on this film, of screenwriter and source novelist author Alec Coppel, director Edward Dmytryk, score composer Nino Rota, and all four of the lead actors, with particular emphasis on Sally Gray, whom he cites as an interesting but now forgotten star of British cinema. He also makes some astute observations about the film itself, and even explains the process used to make coffee in one of the nicest gags.

The BEHP Interview with Gordon K. McCallum (98:10)

One of those cosy chats with often unsung industry veterans conducted for the British Entertainment History Project that have become regular features on Indicator discs – this one, with Obsession’s sound recordist Gordon K. McCallum, was conducted on 11 October 1988 by Alan Lawson. The standard BEHP format is followed here, with McCallum recalling his early days and how his interest in radio and electronics led him to pursue a career in the film industry at the ripe young age of 16. He takes us through his initial work as a studio dogsbody to his promotion to the post of boom swinger, and his later position as a sound recordist and mixer, and having worked on the soundtracks of over 320 films, including many famous titles for prominent directors, he has a lot of stories about their making. These include details on working with David Lean on In Which We Serve (1942), Michael Powell on A Matter of Life and Death (1946), Sergey Bondarchuk on Waterloo (1970), Fred Zinnemann on The Day of the Jackal (1973), Ken Russell on Billion Dollar Brain (1967), and a many more. He reveals that he worked on most of the James Bond films, that he was stricken so badly with flu during the sound mix of A Town Like Alice (Jack Lee, 1956) that he had to leave it to his assistant to finish the job, and cites his Oscar-winning work for Norman Jewison on Fiddler on the Roof (1972) as the most satisfying of all of his film assignments. As ever, an intriguing and educational inclusion, and while Obsession doesn’t get a mention, McCallum does recall working with Robert Newton on the 1942 Hatter’s Castle, noting that the actor, who had a reputation as a heavy drinker, was hitting the bottle even back then and that they could only shoot his scenes in the mornings as a result.

Image Gallery

34 manually advanced screens of promotional photos (including one behind-the-scenes shot), lobby cards, press book pages and article enlargements, and posters for the film, the majority of which have it under its American title of The Hidden Room.

Booklet

Following the full credits for the film, this booklet opens with a fine lead essay by film writer and author of Edward Dmytryk: Reassessing His Films and Life, Fintan McFonagh, who examines the film, the ultimately problematic timing of the John George Haigh acid bath murder case, the circumstances that brought Dmytryk to Britain and to this particular project, and how the meeting of American and British sensibilities resulted in this fascinating film. A July 1949 Talent Spotlight on Edward Dmytryk from Kensington Post and West London Star, in which Obsession is surprisingly not mentioned, is followed by a piece by William McGaffin from the 29 March issue of Evening Star in which it gets some decent coverage in advance of its UK release. Also from 1949 is a 4 September New York Times article by Thomas F. Brady on Dmytryk’s first year in England, and a brief but welcome interview with Naughton Wayne by John Stratton from 25 January edition of Manchester Evening News. Bringing up the rear are extracts from four contemporary reviews, which mostly praise the film, the only critical note being sounded by Monthly Film Bulletin in an otherwise positive piece.

A really well written and splendidly performed slice of gruesome 40s British noir, given a stylistic polish by a talented American director in self-imposed political exile. It’s a most welcome addition to the already impressive Indicator Blu-ray library of oft-forgotten past gems, and the disc boasts a strong transfer from a new 4K restoration and a selection of typically informative and engaging special features. In case I haven’t already made it clear, I really, really liked this one, and this release thus comes strongly recommended.

|