|

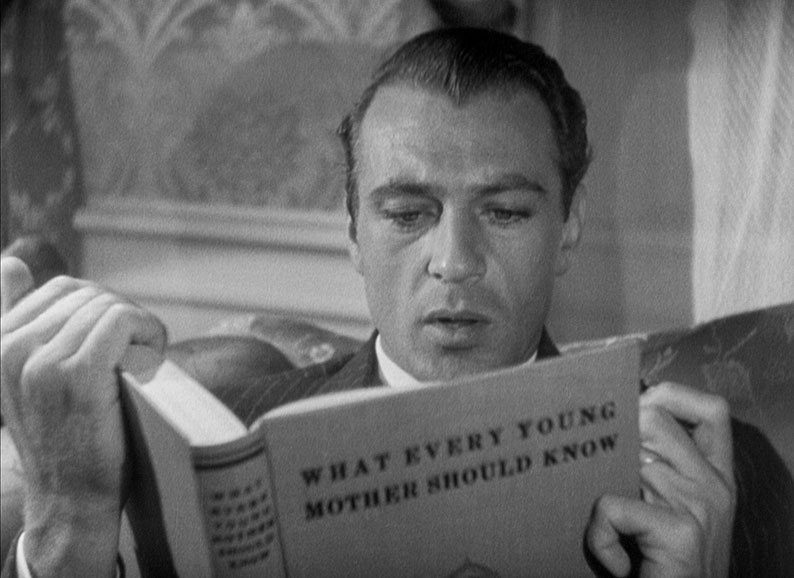

Jerry Day (Gary Cooper) and his second wife Toni (Carole Lombard) are living the high life in Shanghai, but the bills are piling up. Jerry hatches a plan to earn more money, namely by selling the custody rights to his daughter Pennie (Shirley Temple) by his first wife to his former brother-in-law Felix (Sir Guy Standing, with his title listed in the credits) for $75,000. Jerry has not met Pennie before, but when he does, everything changes...

Now and Forever is of three films released as Indicator series Blu-rays by Powerhouse Films directed by Henry Hathaway and starring Gary Cooper, of seven they made together in total. While Hathaway (1898-1985) first established his reputation by directing westerns from Zane Grey novels, he could clearly turn his hand to many genres. While Cooper gets top billing, and Carole Lombard is less in evidence in second, the film had a lot to do with establishing the stardom of the six-year-old billed third, Shirley Temple, who had been making films for two years by that point. It’s the only film where Lombard and Temple appeared together.

The film came out during the Depression, when stories of the rich and monied packed them in. Here we begin in Shanghai and along the way take in New York City and Paris. However, this film has a sour edge to it, as while Jerry Day certainly has money and is not afraid to use it, he’s clearly living beyond his means. All he sees in his daughter is a high-five-figure price tag. However, by meeting Pennie, a child he fathered but whom he is not up to raising, he has a change of heart, almost a meeting of minds.

Written by Vincent Lawrence and Sylvia Thalberg, based on a story by Jack Kirkland and Melville Baker, Now and Forever was released in the US on 31 August 1934, after the Production Code was enforced. In fact, it was the 101st film to receive a Seal of Approval. After 1 July of that year, all films released by major studios had to conform to the code, so bringing to an end the Pre-Code era. Those four years, from the first version of the Code drawn up by Hays in 1930, to the Code’s enforcement, produced many notable films which pushed boundaries in content and language, material which wouldn’t be seen again in studio films for two or three decades. One effect was that Jerry could not be seen to benefit from his crimes, as it’s possible to have done a year or so earlier.

Although there had been plenty of films which were Pre-Code in name only, containing nothing which would disturb the Production Code Administration at the time or later, one effect of the change in Hollywood was a move towards more wholesome fare, and Temple’s stardom was part of that. Now and Forever was one of the reasons for her Juvenile Academy Award the following year. Temple continued acting into her early twenties, but it’s fair to say that her period of stardom was in the 1930s below the age of ten or so. Fashions move on, and the image of Temple in her patented ringlets (hairdressed daily by her mother) and industrial-strength winsomeness and precociousness is one on the other side of history. Yet in Now and Forever her talent is clear and her charm is kept the right side of saccharine. She has a song-and-dance number, “The World Owes Me a Living”. She got on very well with Cooper, who nicknamed her “Wigglebritches”.

Temple was under contract with Fox, who had loaned her out to Paramount. This was her second film there, following Little Miss Marker the previous year. In that film, which had been her first leading role, and this, she is able to reform and redeem errant father figures – or in the case of Jerry, her actual father even if she had never met him before now. And there’s certainly a lot to redeem. The low point is where he uses her teddy bear to hide a stolen necklace. The film was originally to be called Honor Bright, and that phrase recurs in the film indicating if what someone says can be trusted. She is precocious to a fault and is often treated like an adult, though one in a small child’s body. Jerry, on the other hand, is something of a child in a full-grown adult’s body – and at 6’3”, he towers over the not-short-at-5’6” Lombard, let alone tiny Temple. By contrast, Toni is absent for several stretches of the film and Lombard doesn’t make as much of an impression as she would elsewhere. She was a last-minute replacement for Dorothy Dell, who was six years her junior and who had died in a car accident at the age of nineteen. Dell had played opposite Temple in Little Miss Marker and they had become friends. When Pennie bursts into tears when finding the stolen necklace, Temple’s tears were genuine as she had just learned of Dell’s death, the news having been withheld from her until just before she shot the scene. Hathaway, seemingly out of his comfort zone with a drama-comedy like this, puts the story across with considerable efficiency, bringing it in at a lean 82 minutes.

Now and Forever bypassed the Oscars, but it won three Photoplay Awards, for Best Picture of the Month and Best Performances for Cooper and Temple. It was a commercial success and Temple’s stardom was enhanced, to the point where she received between 400 and 500 fan letters a day, needing a secretary to deal with the workload. This was the eighth of nine films she appeared in during 1934, followed by four in 1935 and another four in 1936. Meanwhile, Cooper went on to make The Wedding Night for King Vidor before reteaming with Hathaway for The Lives of a Bengal Lancer, but that’s another Indicator Blu-ray and another review.

Now and Forever is spine number 471 in the Indicator series, a Blu-ray release encoded for Region B only. An A certificate in British cinemas in 1934. it now has a PG.

The film was shot in black and white 35mm, and the Blu-ray transfer is in the correct aspect ratio of 1.37:1. The transfer is derived from Universal’s HD remaster and is at times a little soft, which is no doubt due to the original nitrate materials. Sunlit exteriors are sharper and the grain looks natural and filmlike.

The sound is the original mono, rendered as LPCM 1.0. The film is a product of Hollywood expertise and this track is clear with dialogue, sound effects and music well balanced, with a small amount of hiss attributable to the recording technology of the time. English subtitles are available for the hard-of-hearing and I didn’t spot any errors in them.

Commentary by Pamela Hutchinson

Pamela Hutchinson adds to her list of commentaries on 1930s Hollywood film with a thorough piece on this film which is easy to dismiss by the Temple-allergic. She fills in a lot of background detail without being too scene-specific, including much about the film’s place in the sea-change in Hollywood brought about by the Production Code. Hutchinson reads the film as something of a male version of the much-filmed Stella Dallas (already done as a silent in 1925 with Belle Bennett and later remade in 1937 with Barbara Stanwyck and 1990 with Bette Midler). She also talks about the original ending of the film, which isn’t the one which ended up on screen.

Bright as a Penny (15:27)

Christina Newland begins by saying that there were child stars before and after Shirley Temple, but even if you haven’t seen any of her films her image has been enduring, more so than, say, Baby Peggy’s in the silent era or Jackie Coogan’s or Mickey Rooney’s. It certainly overshadows her later career as a diplomat, which included stints as the US ambassador to Czechoslovakia and Ghana. Some of this was certainly due to timing, with her persona enabling escapism in an America emerging from the Depression, with her fans including President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Temple started out in Baby Burlesks, a series of short films sending up contemporary films with a cast of pre-school children, which look from the stills distinctly problematic by today’s standards. While this is a profile of Temple, inevitably there’s much emphasis on the film whose disc this appears on. It’s also the only one of which we see extracts, given that it’s the one Powerhouse have under licence: other films are represented by posters or stills. There is some discussion of her relationships with Cooper and Lombard, and repeats the story (see above) that her tears in one scene were real. Newland also tells a story about MGM producer Arthur Freed and the disturbing reason why she didn’t make a return to the screen in the late 1940s.

Theatrical trailer (1:41)

This may well be a reissue trailer, as it begins with “brought back to delight you”. It certainly knows where its bread is buttered as there’s a heavy emphasis on the stars, Temple in particular. Sir Guy Standing has a brief look-in at the end.

Image gallery

Sixty-one of them, as usual navigable via the NEXT button on your remote. Most of them are stills, some showing us behind the scenes, forty-two of them in black and white, two in colour (for this monochrome film), plus ten front-of-house cards and six poster designs.

Booklet

Indicator’s booklet with this limited edition runs to thirty-six pages. (When the initial run of 3000 copies sells out, any future standard edition will not contain the booklet.) Nathalie Morris begins with “Honour Bright”. This is an overview of the film’s production and an examination of its themes, especially the issue of money at a time of Depression. Among the things we learn from the film is that an overdrawn bank account could land you a prison sentence in France. Yikes. Morris also mentions that Temple’s monetary value (on or off screen) is a theme of some of her other films. She also cites Graham Greene’s infamous review of Wee Willie Winkie (1937, in which Temple was directed by John Ford, no less), which suggested that Temple’s appeal to adults could be less than savoury. Temple and 20th Century Fox sued him for libel as a result.

Henry Hathaway is up next, with “A Jolly Film Director”, from the Kansas City Star in 1934. “So you want to be a film director?” he asks at the start, and you may not want to be when you reach the end of this piece. Hassles abound, such as wardrobe issues with the stars who are present, your juvenile lead off with mumps and Cecil B. De Mille preventing you from doing process shots due to his own film (Cleopatra) being in production at the time.

Next up are a few items about Shirley Temple, from various US papers in 1934. So we see her beat Cooper at checkers (she’ll let him win next time) and her mother Gertrude revealing that instead of her being a homemaker for her husband and two other children, she now works full-time for her world-famous daughter.

Henry Hathaway reappears, this time being interviewed by Polly Platt about his career in 1973. In this extract he talks about Now and Forever, and reveals how screen-smart Temple was even at her young age. (She changed a telephone from one hand to the other so that the handset didn’t obscure her face for the cameras.) Also in the booklet are contemporary critical quotes from both sides of the Atlantic (including a brief bit from the Monthly Film Bulletin in its first year of existence), a cast and crew listing and plenty of stills.

Now and Forever is a product of a specific time in American film history, when screen entertainment was changing as the Depression lifted and the Production Code came into force. It’s also a reasons why Shirley Temple was one of the biggest stars of the 1930s, and it’s a credit to Gary Cooper that he is not completely upstaged. As usual, the film is well presented on Indicator’s disc and while the extras are fewer than with other releases, all are very useful.

|