|

The early twentieth century, on the northwestern frontier of British India. Two soldiers arrive to join the 41st Bengal Lancers: Lieutenants John Forsythe (Franchot Tone) and Donald Stone (Richard Cromwell). Lieutenant Alan McGregor (Gary Cooper) is put in charge of them. Stone is the son of the commander Colonel Stone (Guy Standing). Meanwhile, Lieutenant Barrett (Colin Tapley), in disguise as an Indian and undercover, reports that Mohammed Khan (Douglass Dumbrille), Oxford-educated and supposedly a friend of the British, is planning an uprising...

The Lives of a Bengal Lancer came out in 1935, and was one of a cycle of films dealing with the history of various outposts of the British Empire. A popular hit in its day, it’s one of those films which stands up well nowadays, along with Gunga Din from four years later. At the time, Britain and what remained of its Empire were major overseas markets for Hollywood, so the films were made to appeal to those countries and by and large they did. Not everyone approved, of which more below.

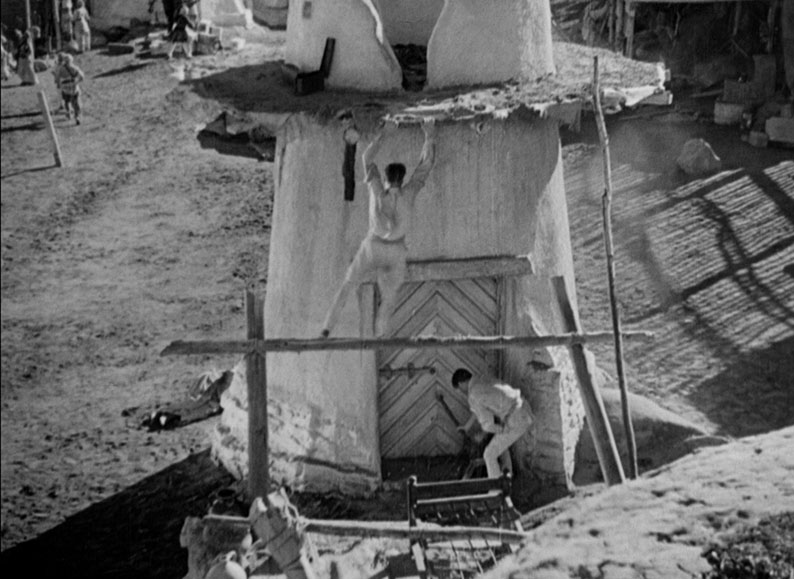

The film is “suggested”, as the credits put it, by Francis Yeats-Brown’s book of the same title, published in 1930. (Screenwriting credits go to Waldemar Young, John L. Balderston and Achmed Abdullah, with Grover Jones and William Slavens McNutt listed for their adaptation.) However, the source text was not a novel, despite what the credits say, but a memoir, and by all accounts nothing of the book survives in the film other than the title. Paramount bought the rights before the book was published, no doubt sensing a hot property. The production was complex. The first director assigned, in 1931, was Ernest B. Schoedsack, who, with Merian C. Cooper, had directed the silent documentary features Grass (1925) and Chang (1927). He was despatched to India to shoot footage, likely to be used as second-unit work. There are some stock shots in the finished film, mainly at the start, possibly partly shot by Schoedsack, but the film was otherwise entirely made in the USA. Desert locations in the much-filmed Lone Pine, California, were supplemented by matte paintings, and there was some work at Red Rock Canyon in Nevada. Schoedsack left the production and he went on to make King Kong (1933) with Merian C. Cooper and its sequel Son of Kong (also 1933) solo. Another director assigned was Stephen Roberts, best known now for The Story of Temple Drake (1933), based on William Faulkner’s then-notorious novel Sanctuary, and one of the films credited or blamed for the Production Code being enforced on the studios in 1934. After other actors had been considered, Gary Cooper took the lead role. After having worked with Henry Hathaway on Now and Forever the previous year, he suggested Hathaway for the production. That earlier film, with a leading role for Shirley Temple opposite Cooper was hardly similar to this very male-skewing (only one credited female role) historical action-adventure, but Hathaway had begun his career working for Allan Dwan and had started directing on Zane Grey westerns in the early-talkie era. Bengal Lancer was his first big-budget studio production. The film isn’t quite the action piece it may seem at first sight: Hathaway and his writers build up to a big climax, with a few setpieces (such as a boar hunt, presumably faked and/or making use of stock footage, as it hasn’t been cut by the BBFC) along the way, but with much emphasis on the characters of the three leads and a not insignificant amount of humour. Given Hathaway’s background in westerns both before this film and after (he was one of the three directors of the big-budget Cinerama production How the West Was Won, from 1962), there’s a lot of the genre in this film. Efficiency was Hathaway’s watchword, and he keeps a tight hold on this film. The marks of a big-budget A picture are everywhere to be seen, from Charles Lang’s cinematography to the production and costume design.

Needless to say, some aspects of films like this are problematic to modern eyes. You have to expect uses of darkface (in this black and white film) and they are there, the main example being Mohammed Khan, played by the Canadian actor Douglass Dumbrille, who played many nationalities in his career. Some of this is due to the plot, with white soldiers in disguise as Indians. But the result isn’t anywhere as jingoistic as it could have been. That said, Muslim organisations complained about the portrayal of members in their faith, due to two scenes in the film. Italy under Mussolini banned Bengal Lancer. However, it was one of eleven American films considered artistically valuable by the Nazi regime in Germany between 1933 and 1937 and, somewhat alarmingly, it was a particular favourite of Hitler’s.

The Lives of Bengal Lancer gained seven Oscar nominations, winning one: Clem Beauchamp and Paul Wing in the now-obsolete category of Best Assistant Director. Its other nominations were for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Writing, Screenplay, Best Art Direction (Hans Dreier, Roland Anderson), Best Sound Recording (Franklin Hansen) and Best Editing (Ellsworth Hoagland). The Best Picture winner that year was Mutiny on the Bounty, for which Franchot Tone was one of three Best Actor nominees, though they all lost to Victor McLaglen for The Informer.

Number 472 in the Indicator series, The Lives of a Bengal Lancer is released on Blu-ray on a single disc encoded for Region B only. The film had a U certificate in British cinemas in 1935 and retained that on DVD in 2000, but it is now a PG.

The film was shot on black and white 35mm and the Blu-ray transfer, derived from Universal’s 4K restoration (Universal own the rights to almost all of Paramount’s catalogue from this era), is in the correct Academy Ratio, namely 1.37:1. There’s a slight softness to the image and quite a lot of grain, but that’s to be expected from a production of this era. The source material seems in good shape, with some minor damage. In HD, the uses of stock footage, becomes quite obvious.

The soundtrack is the original mono, rendered on this disc as LPCM 1.0. There’s not much to say here, with the dialogue, music and sound effects well balanced. English subtitles for the hard of hearing are optionally available and I spotted no errors in them. They go so far as to indicate which language is being spoken with short untranslated non-English exchanges: Hindi and Pushtu (or Pashto). They also get the national anthem right – “God Save the King” – as, while no date is specified, Yeats-Browne served in India during the reign of Edward VII.

Commentary by C. Courtney Joyner and Steve Latshaw

Screenwriter/novelist Joyner and filmmaker Latshaw double up on this disc’s commentary. One of the benefits of a dual commentary is the rapport between the participants (or not, as the case may be) and that’s a benefit here. Joyner states upfront that he’s a Henry Hathaway fan, and it’s inevitable that there’s a lot about his life, character and his long career which extended into the 1970s. Unlike others of his generation, Hathaway could move with the times. For example, he was an admirer of The Wild Bunch when other older directors were quick to disparage Peckinpah’s film. His directing style changed over the years, with later often having actors moving and interacting in front of a static camera, but there are quite a few uses of mobile camerawork in Bengal Lancer. Cinematographer Charles Lang, who worked with Hathaway several times, has his share of shout-outs, for his colour work as well as his black and white (as here). There is also an account of co-writer John L. Balderstone, a playwright as well as a screenwriter, who could be said to have laid the foundations for several genres. He was well versed in horror (the 1931 Dracula, an early script for the 1931 Frankenstein, 1932’s The Mummy) and also wrote or co-wrote such as The Last of the Mohicans (1936), The Prisoner of Zenda (1937) and Gaslight (1944) as well as contributing uncredited to Gone with the Wind (1939). Clearly a very undersung figure, with an affinity for British subjects even though he was born in Philadelphia. Gaslight gained him his second Oscar nomination, the first being for the film in hand. Gary Cooper gets less of a look-in, though Joyner and Latshaw do point out how much his acting relied on underplaying. An informative and entertaining commentary.

Service and Sacrifice (26:25)

Sheldon Hall begins this informative featurette by discussing Francis Yeats-Brown’s book, and the fact that the rights were snapped up by Paramount, presumably with the aim of making a follow-up to the studio’s 1929 hit The Four Feathers (made as a silent, though released with synchronised music and sound effects). Hall discusses the production of the film, with the many hands involved in writing and direction, particularly the Crimea-born of Afghan heritage Achmed Abdullah – this nicely balances the commentary, which doesn’t mention him. The various casting options are also discussed, with Fredric March attached at one point and Henry Wilcoxon beginning production before being dropped in favour of Gary Cooper. (According to Henry Hathaway, that is. Other sources suggest that Wilcoxon was to play Franchot Tone’s role.) There is a contrast between the three American leads and the British actors playing the older soldiers, given that the characters are all meant to be British. No doubt commercial considerations had a say there. Hall also describes the cycle of films on the British Empire, which had run its course by the end of the decade and the outbreak of World War II. In the UK, the main concern of senior BBFC examiner Colonel Hanna was that military subjects were accurate, and some of his corrections made their way into the finished film. Hall more than once cites the work of historian Jeffrey Richards, though doesn’t always agree with him.

Lux Radio Theatre: The Lives of a Bengal Lancer (53:38)

In the 1930s, in the absence of a television service, radio was the home medium of choice. Partly to advertise what was on at your local cinema, or maybe to complement or revisit it, quite a few films ended up on the wireless in versions cut down from the full version – in this case, to about a third of its length. Sometimes the broadcasts included actors from the film. Here it’s the turn of The Lives of a Bengal Lancer on 10 April 1939, with Errol Flynn, Brian Aherne and Jackie Cooper taking the three lead roles and C. Aubrey Smith and Douglass Dumbrille reprising theirs. Cecil B. DeMille introduces the production, which is divided into three acts. During Acts Two and Three, DeMille brings on a guest, a real soldier: General Hugh Samuel Johnson. The film is a favourite of his, and he had seen it four times and says that its sights and sounds would be as poignant to many a soldier as “peat smoke to an Irishman”. After the play, there’s some banter between the cast, with Smith having a go at the others for playing the “sissy game” of cricket. There is also a plug for a daytime radio soap, The Life and Love of Dr Susan, “the story of a young and attractive woman doctor struggling to make life worthwhile for herself and her two small children”. (It ran from 13 February to 29 December that year in fifteen-minute episodes, of which just one survives.) Next week: Bullets and Ballots, with the intriguing prospect of a cast featuring Edward G. Robinson, Mary Astor and Humphrey Bogart.

Theatrical trailer (1:42)

As you might expect, this trailer emphasises the action, with several shots and one large explosion from the final battle. Transferred from an original which has clearly seen better days.

Image gallery

Seventy-six stills, front-of-house cards and poster designs, navigable by the forward and back buttons on your remote.

Booklet

Indicator’s booklet, available with this limited edition of 3000 (future standard editions will not include one), runs to forty pages. The main essay is “A Man’s Got to Be Seasoned” by Sam Wigley. He points out that, given that Cooper and Hathaway’s names have less currency now, the film’s lasting legacy may be the war-movie cliché “We have ways and means of making you talk”. (Actually, that may come from Odette (1950). In Bengal Lancer, Mohammed Khan actually says, “We have ways to make men talk.) Wigley goes on to describe the film’s lengthy production, with its changes of director and leading men. Cooper’s work with Hathaway is discussed as is Cooper’s form in desert-set military stories, such as his work opposite Marlene Dietrich in Morocco (1930, on which Hathaway was assistant director) and with a change of armed force to the French Foreign Legion in Beau Geste (1939). The trend of Empire pictures (with much of the contemporary audience old enough to remember the times) faded with the outbreak of World War II but returned in the 1950s and 1960s. Wigley finishes by making a surprising comparison with a much later film, Zero Dark Thirty (2012).

“Perfect Paradox” is a lengthy contemporary article by Molly Marsh from the Oakland Tribune of 25 November 1934. It describes how Yeats-Brown’s book has been adapted for the screen, or in Marsh’s words, “torn to shreds and pasted together again”, including an account of the man himself visiting the production, seemingly indifferent to how his book might turn out on the screen. This is a look at the film while still in production and of course no way of telling success or failure. She ends by saying that she is betting on the cast and crew to “come through with colours flying and to give us who wait ‘out there’ in darkened theatres a rare experience”. Maybe she saw the finished film and had her wish.

Over to Polly Platt, who met Hathaway in 1973 for a book-length interview published in 2001. We had an extract from this in the Now and Forever booklet and so here we are again with The Lives of a Bengal Lancer. Hathaway talks about how he came to be attached to the film. On the location shoot at Lone Pine, Hathaway – who had been to India – wanted an elephant to help the illusion that the California desert was actually India, and one was eventually forthcoming.

The “Critical Response” section features extracts from reviews in the Monthly Film Bulletin and the New York Times, plus an article from the latter about Conservative MP Arnold Wilson complaining about the film’s portrayal of Muslims. Also in the booklet are cast and crew listings and plenty of stills and poster designs.

Harking back to an age that was vanishing then and has vanished now, The Lives of a Bengal Lancer was one the most successful of the cycle of British Empire pictures and survives as precision-tooled mainstream Hollywood entertainment. As ever, Indicator’s extras are informative and help put the film in its context.

|