|

For a number of reasons, I came relatively late to Czech New Wave cinema. Back before such films became available on home video formats, access to them was seriously limited in the UK, at least for anyone not living in or close to the capital city and its once-splendid array of independent cinemas. More recently, when Second Run started sending us discs of Czech New Wave titles for review, they tended to be covered by former site writer L.K. Weston, who had a passion for these films and whose knowledgeable reviews prompted Second Run at one point to specifically request that she be the one to cover their next release. When she moved on to pastures new I'll admit that we languished for a while. My previous lack of exposure to these films meant that I felt ill-equipped to pass even remotely authoritative comment on them, but eventually found the time during what proved to be a difficult period of my life to take the long-delayed plunge. That was when I had one of those "oh now I get it" lightbulb moments of realisation. It no doubt helped that the first Czech New Wave title I chose to review was Juraj Herz's extraordinary The Cremator. There really was no turning back after that one.

French, British and Czechoslovakian cinema all had their New Waves, and while they had much in common, each was distinctive in its look and feel. What remains unusual about the 1965 90º in the Shade [Třicet jedna ve stínu] is that it brings together elements of Czech and British New Wave cinema in a single film. Well, sort of. Two versions of film were produced, one with the dialogue in English and the other in Czech, and each had a different and country-specific editor. The producer and four of the five lead actors were British, but the film is set in Prague and had a Czech director, and while the screenplay is credited to celebrated British writer David Mercer on the English language version, on the Czech release that credit is shared with director Jiří Weiss and his countryman Jiří Mucha. And despite the presence of those British actors, even the English-language version of the film feels more like a work of Czech New Wave cinema than a product of its British counterpart.

The first character we meet is slightly portly Kurka (Rudolf Hrušínský), about whom we are invited to speculate when he sits down for sausages and beer at a riverside café on a sweltering summer's day dressed in a suit and tie, while everyone around him swims and sunbathes wearing the minimum that public decorum will allow. He looks painfully out of place, yet despite his lack of cheer he looks oddly comfortable in his chosen attire – it's hard to imagine this man would ever get naked even to shower. That he looks and acts a little like someone who has come to this spot to ogle half-naked women is seemingly confirmed when he fixates on the sunbathing Alena (Anne Heywood), who pays him no heed even when he turns to watch her as she walks right past him.

A short while later, Kurka meets up with his far cheerier colleague Bažant (Donald Wolfit), and the two head to a grocery store run by the combine for which they both work to carry out a surprise audit, a store in which Alena is the assistant manager. The look of surprise on Kurka's face makes it clear that he instantly recognises her as the woman he was so captivated by a short while ago, while Alena's awkward response suggests that she may have been all too aware of his earlier gazing after all. Or is there something else that's bothering her about his presence? The easy-going Bažant is well known to the shop's employees and is clearly well liked, while the fastidious Kurka is new to this district and humourlessly picky about every detail of his duties. He's thus less than happy about a discrepancy in the day's takings, and is unwilling to overlook the fact that shop worker Rosa (Věra Tichánková) borrowed from the till when she forgot her purse that morning. He's not persuaded by the news that she left a receipt for the borrowed money, or by Bažant's attempt to downplay its importance, but when Alena claims she knew all about it and replaces the missing money, he suddenly seems willing to just let it go.

By this point we've been clued into the fact that something is really bothering Alena by her urgent attempt to make a phone call in the store room, a call that is cut short when Kurka walks unexpectedly in. His presence clearly makes Alena uncomfortable and his barely concealed and frankly rather creepy interest in her makes it easy to see why, and if you had any doubts that something is amiss here, the discomforting off-key pulses of Ludek Hulan's largely jazz-driven score are on hand to provide confirmation. At one point, Alena even feigns illness and as soon as Kurka's back is turned is glancing urgently at her watch, but when a blown fuse plunges the shop into darkness, an accident with a coffee cup proves a trigger for things to suddenly mellow between the two. It's then that shop manager Vorell (James Booth), returns from an unspecified errand, and Kurka elects to complete the audit the following morning.

It's here that I was a little thrown. As the shop closes up for the night and everyone goes their separate ways, I expected that we were going to stick with the troubled Alena, who by then had been tentatively established as the central character, but instead she heads off home and we follow Kurka instead. The curse of character convention had led me to assume he lived a solitary and rigidly orderly existence in a pristine apartment, but instead he shares an untidy flat with a son he is at odds with and an alcoholic wife (played by British actress Ann Todd) who appears to despise him. In just a matter of minutes he is transformed from being the film's probable antagonist into a man who is worthy of our sympathy. What's that about not judging by appearances?

The intrigue regarding Anna's situation continues as she urgently pesters her sister and brother-in-law for money for reasons that are a teasing amount of time in coming, and while I'm not about to get into the specifics, I will say that it relates to her relationship with married shop manager Vorell, details of which are revealed through a series of nicely timed and economically handled flashbacks. By this point their personal relationship has stalled, but while Alena is of the view that the affair is over, Vorell is still convinced that he's in with a shot. It's something Alena is quick to dismiss when they furtively meet that evening and the reaons for Alena's anxiety is revealed. Despite this, she remains loyal enough to him to put herself in jeopardy in order to help cover up his misdeeds, a loyalty that will later prove to be tragically one-sided.

As their story unfolds it become evident that Kurka and Alena have more in common than surface impressions might suggest, two lonely souls whose fates have been shaped in part by uncaring others. It's something Kurka seems to recognise in Alena without knowing how to respond to that realisation, and his eventual understanding of what she may have sacrificed and why it comes too late for him to take effective action. Kurka may be more of a stickler for the rules than his laid-back colleague or even his immediate boss, but he's the only one who suspects the truth when events later cast Alena in a negative light, a response that feels triggered more by empathy than repressed desire. Whether his final through-the-window look (I can't say more on this) is one of frustrated emasculation, vengeful intent or both is left for us to interpret.

Despite the almost burned-out brightness of the weather that gives the film its opening title (the Czech title temperature is 30 degrees – they were way ahead of us in adopting centigrade as the standard measurement) and the joviality of Bažant's early banter with the shop employees, a shadow is cast over events that is initially only hinted at, as much through the production design as the words and actions of the actors or the way the mood of a scene is transformed by the music that underscores it. Of course, I may well be reading false meaning into art direction that was designed simply to be an accurate reflection of the location and time, but seemingly everywhere there is what feels like expressionistic evidence of decay and neglect, from the dank stains that blight the kitchen wall of Kurka's apartment to the flaking paint on the window frame in the office of Kurka's and Bažant's boss. Just as characters appear almost conditioned to be indifferent to the crumbling state of their homes and workplaces, they are seemingly insensitive to the feelings of someone whose happiness, future and even life they unknowingly hold in their hands.

One aspect that may initially prove a small barrier to total immersion is, perhaps ironically, also one of the things that makes 90º in the Shade so unusual and intriguing. As a co-production between Britain and Czechoslovakia, the film features a mixed cast of Czech and British actors, all of whom delivered their dialogue in their native language, and the decision to create separate Czech and English language releases meant that the actors not speaking the language of the version in question had to be dubbed by local performers. With this in mind, the advantage of the English-language version is that most of the lead actors deliver their dialogue in the language being spoken. The disadvantage is that Rudolf Hrušínský, a masterful actor whose work I was introduced to through the aforementioned The Cremator, has had his voice replaced with that of a prissy Englishman. Now I'm not knocking the work of the voice actor here, whose diction and delivery are both appropriate for the character as written, it's just that it was clear to me from the off that this voice just doesn't belong to the man I was watching on screen. In the Czech version the mismatch of voices to mouths on the British actors is even more pronounced, but Hrušínský's voice is his own here, and his already fine performance thus feels more complete. Both versions thus have their vocal plusses and minuses, but it's a testament to the film that long before the halfway mark I stopped even noticing the dubbing.

90º in the Shade starts intriguingly and evolves into a gripping tale that studiously avoids sensation or overstatement, grounding the characters and events in a reality that will be instantly recognisable even to those who've never set foot in Prague. It's this, coupled with a string of fine performances and the injustice of the gender politics at play here (again, I can't elaborate without giving more plot details away) that make this such an involving and ultimately affecting work. It left me saddened, a little haunted, but enriched nonetheless, and served as a timely reminder that while not all men are the bastards of gender politic legend, a dispiriting number are still willing to walk callously or indifferently over others in pursuit of their own self-serving agendas.

The 2K restoration of 90º in the Shade was carried out by Powerhouse Films at Final Frame Post in London from the original 35mm camera negative, and the results are impressive. Detail tends to look sharper on closeups than on wide shots (I've encountered this before with anamorphic lenses), but the best material is really crisp, though there are intermittently shots that have a slightly blurred look, which I'm guessing was down to the condition of the source material. The contrast is nicely balanced, nailing the black levels without ever having an aggressive feel, and while some exterior shots look a little overexposed, I have a feeling this was an intentional move on the part of Weiss and cinematographer Bedřich Baťka to expressionistically convey the daytime heat that gives the film its title. Dirt and damage has been digitally cleaned up and there is a fine film grain visible throughout. The framing is the original 2.35:1.

Třicet jedna ve stínu was supplied in HD by the Czech National Film Archive (Národní filmový archiv) and is in less pristine condition than the newly restored English language version. The contrast is slightly more pronounced but the detail is still crisp, though there are noticeably more dust spots and the odd small scratch is visible.

Both versions have remastered Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtracks and both have clear reproduction of dialogue and music, albeit within the expected range restrictions for a film of this vintage. Surprisingly, perhaps, the Czech soundtrack feels a little livelier and is a couple of notches louder than its English counterpart.

Optional English subtitles kick in by default on the Czech language version, and English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are available for the English language print. Impressively, SDH subtitles have also been provided for all of the short films in the special features.

Audio Commentary with Michael Brooke

I can't help wondering if writer and critic Michael Brooke secretly wishes the films he commentates on were a little longer to give him a chance to take the occasional breath, though I suspect he'd probably pack any extra space with even more information. As ever, this one is crammed to the gills with details about the film and its makers, plus some compelling analysis of some of its elements, themes and characters. We get a Kafka quote about one of the locations, a revealing explanation of why this intimate drama was shot in scope, info on the factual incident that inspired the story, and Brooke even credits the sources of the research he conducted specifically for this commentary, something I heartily salute. An excellent extra.

Degrees of Separation (21:57)

For those of us who've only seen each version once or twice, Michael Brooke is back with a breakdown of some of the key differences between the Czech and English cuts of the film using comparative extracts, over which he commentates. He discusses the alternate cuts and uses them as jumping-off points to talk about some specifics of Czech grammar, why the spelling of the British names is different on the opening credits of the Czech language version, footage that is unique to either cut, the differences in their use of sound, and more. A really useful extra.

The Rape of Czechoslovakia (17:48)

The first of four propaganda shorts included here that were either directed, edited or directed and edited by Jiří Weiss while he was based in Britain during World War 2. This 1939 piece is briskly assembled but unsurprising, painting the Czechs as an inherently peaceful people whose seemingly constant celebration of life has been crushed by the jackboot of the invading Nazi army. What's interesting is just how much of the running time is given over to showing us how life in the country was before the Nazi invasion, which is symbolically signalled by the outbreak of a thunderstorm.

The Other RAF (8:02)

A Weiss-directed and edited short from 1942 about the Russian Air Force, one whose breezy editing is its strong point, though the footage of Russian airmen doing synchronised folk dancing is unexpectedly delightful. "Look at these Nazis," the narrator says with barely concealed contempt over footage of captured German pilots, "Young in years but old in murder."

100,000,000 Women (8:06)

A Weiss-edited documentary short from 1942 that looks at the role played by Soviet women during World War 2, with footage of women working in a variety of traditionally male jobs set partly to the instantly recognisable Troika from Prokofiev's Lieutenant Kijé, Op. 60. The film itself proves interesting for both expected and unexpected reasons. The images themselves do play to a once-common image of Russia as a country whose women were as tough and hardy as its men, but what caught me out is that the images female firefighters, train drivers, crane operators and engineers still looks convention-breaking today, because even all these years later these professions are still dominated by men. It brought to mind Connie Field's excellent 1980 documentary, The Life and Times of Rosie the Riveter, which served as a handy reminder that the favourite sexist claim that there are jobs that women just can't do flew out the window when the outbreak of war left a sizeable hole in the workforce, one that these very women were quickly able to fill. Up yours, patriarchy! The film ends with a boisterous appeal from Claudia Nikolayeva, Secretary of the Central Council of Soviet Trade Unions, whose metal-capped teeth predate those worn by Marilyn Manson by over a half a century. And yes, I'm aware that's not remotely relevant.

Before the Raid (34:37)

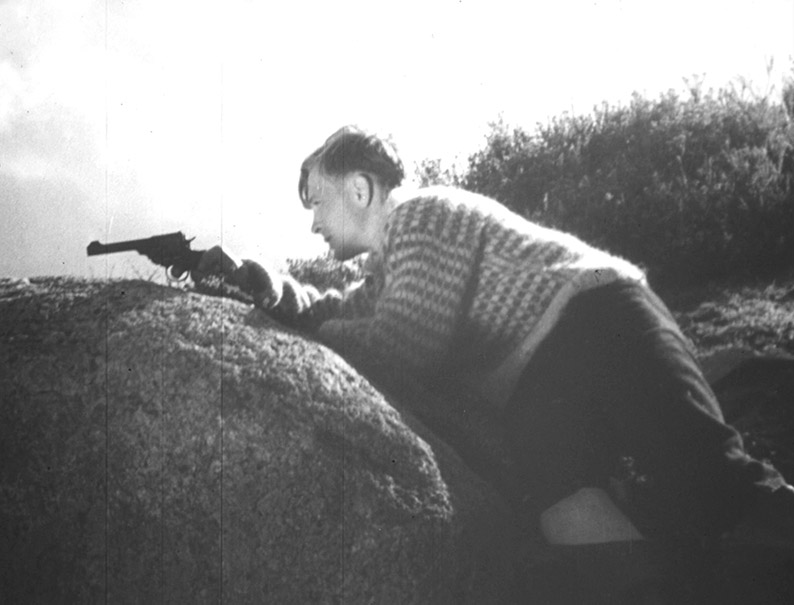

The longest of the short films here (and I do realise how contradictory that sounds) was directed by Weiss and written by celebrated author Laurie Lee, and is a dramatized account of actions taken by a group of Norwegian fisherman against Nazi soldiers that were occupying their village. And it's really something, being tightly directed and boasting an almost documentary air of realism, while the running battle that follows a defiant uprising is thrillingly staged. What particularly impresses for a wartime work is that the Norwegians and Germans both deliver dialogue in their native tongues and neither language is vocally translated or subtitled for clarity. Then again, it doesn't need to be, so effective is Weiss's visually-centric storytelling here. The finale, in which fisherman use their boats to outwit their armed German escorts, is particularly neat. I enjoyed the hell out of this, and its warning about the tactics of oppression – "Starve the people, and they'll do what you want" – still applies to both the international and domestic politics of today.

The IWM Interview with Jiří Weiss (25:14)

An engrossing audio interview with director Jiří Weiss, who relates the story of how he navigated his way from Czechoslovakia to London during World War 2 via an invitation from documentary guru John Grierson and some colourful adventures en route. We get a hearty recommendation for the quality of Dutch jails, and details of where Weiss's film career went following his arrival in London, including brief discussion of the making of Before the Raid, under which this interview runs in the manner of a commentary track.

Booklet

The lead essay here is by Jonathan Owen, who examines the film and its making in enjoyable and sometimes revealing detail. This is followed by a short but useful extract from a 1974 interview with director Jiří Weiss in which he talks about the film's production. Up next are extracts from two reviews of the film, the second of which was written in 2011 by Anthony Nield, who also provides an overview of Weiss's wartime film work. Credits for the main feature and the four short films have also been included, and the booklet is illustrated with promotional photos and a Czech poster.

It has been noted before by writers on this site that one of the pleasures of reviewing discs from dedicated independent distributors like Indicator is that you get to see films you might otherwise have missed, and that's certainly the case with 90º in the Shade. Although a film I was not even aware of before the press release for this disc landed in my inbox, it's one that I was quickly intrigued and gradually pulled in by, before being hit with an emotional gut-punch that sadly still has social relevance today. Two cuts of the film, a great restoration on the English language version and some first-rate extras make this another winner from Indicator. Heartily recommended.

|