|

If you come to The Cremator [Spalovac mrtvol], the third feature from prolific Czech director Juraj Herz, with little knowledge of its content, its characters or its setting, then it could take you a little while to get your bearings. Following an intriguingly edited, pre-title trip to the zoo, during which we are introduced to lead character Karl Kopfrkingl and his 'decent, perfect family', we then watch him hosting a sizeable reception, at which guests are forbidden to smoke and denied alcoholic beverages. "When you die, there is no smoking or drinking for all eternity," he tells one male guest, as he gently strokes the man's hair and extinguishes his cigar. The event, it turns out, has been organised by Karl to raise customer awareness of the advantages of cremation over burial, a subject about which he is able to wax lyrical. There is little indication at this point of when the film is set, and as a key work of the celebrated Czech New Wave, the expectations are that it is taking place in the 1969 equivalent of the here and now. It's only when Karl's former army comrade Reineke starts enthusing about Hitler and his policies, and Karl advises his teenage son Mili to brush up on his German, that the koruna begins to drop. This is 1939 Prague, shortly before the German occupation, and the country is on the brink of monumental upheaval.

Initially, this plays as little more than background detail to a portrait of a man with a shared passion for his family and his vocation as a cremator, a process that he believes is not simply about disposing of the remains of the departed, but is one that liberates their souls and brings an end to their earthly suffering. In the company of the bullish Reineke, he initially seems less comfortable, but in the course of their discussions he gradually becomes seduced by the man's propagandist banter, to the point where all other aspects of his life become secondary to this dangerous new calling.

In many ways, Karl is a man of ordinary pleasures and vices, though each is touched with a quaint eccentricity. When buying a present for his wife, for example, he selects a framed portrait of Nicaraguan President Emelian Chamorro, while his cheerful visits to a local brothel are confined, for undisclosed reasons, to the first Thursday of every month. But it's his work at the crematorium that brings him the most satisfaction, a world we are introduced to when he takes new employee Dvorak on a tour of this "temple of death,” introducing him to his co-workers and outlining his duties with an unsettling blend of practicality and grimly comic poetry: "These furnaces," he tells Dvorak, "always remind me of the ones in which our daily bread is baked."

The most striking aspect of The Cremator is not its characters or the increasingly disturbing direction taken by its narrative in the later stages, but the sometimes extraordinary nature of its cinematic handling. A clue to which other Czech filmmaker's work the film feels stylistically wedded is provided by the mere presence of an introduction by the Brothers Quay, and had I not known in advance that the director was Juraj Herz, I could have sworn I was watching an early work by the great Jan Svankmajer. This is firmly established in the opening family trip to the zoo, a disorienting but captivating montage of oddly framed close-ups and rapid-fire editing that feels loaded with hidden meaning and subtextual suggestion. The animated title sequence and lightning-cut montages that follow have Svankmajer written all over them; it should perhaps thus come as no surprise that Herz and Svankmajer were contemporaries who both started out in puppetry and theatre and – unlikely as it may seem – were actually born on the very same day. Herz even acted in Svankmajer's 1964 directorial debut, The Last Trick [Poslední trik pana Schwarcewalldea a pana Edgara].

This signature use of extreme close-ups and quick-cut editing peppers the film's first third and is often wittily employed. A Svankmajer-esque fascination with mouths includes a brief but memorable shot of the family cat audibly licking its lips at the prospect of fishy left-overs, while Karl's indecision over where to hang a new picture is visually realised as a series of flash-cuts of him holding it up in various parts of the room. Later, the technique is put to more overtly political use, as Karl is seduced by Reineke's talk of party meetings and membership, and the pictures of naked women with which he is being tempted are intercut with the more sinister wording of the party membership document he is simultaneously being encouraged to sign. Herz also puts his unique stamp on the look and dramatic flow of the film, not least in the beautifully executed scene transitions, where an action that is seemingly alien to one sequence is more logically concluded in the next, with the unbroken flow of dialogue providing an almost invisible bridge. As the film gradually transforms from a layered social drama into a psychological and darkly political horror story, this signature use of close-ups gives way to some deeply unsettling extreme wide-angle imagery, an expressionist technique employed to present events from Karl's increasingly disturbed viewpoint.

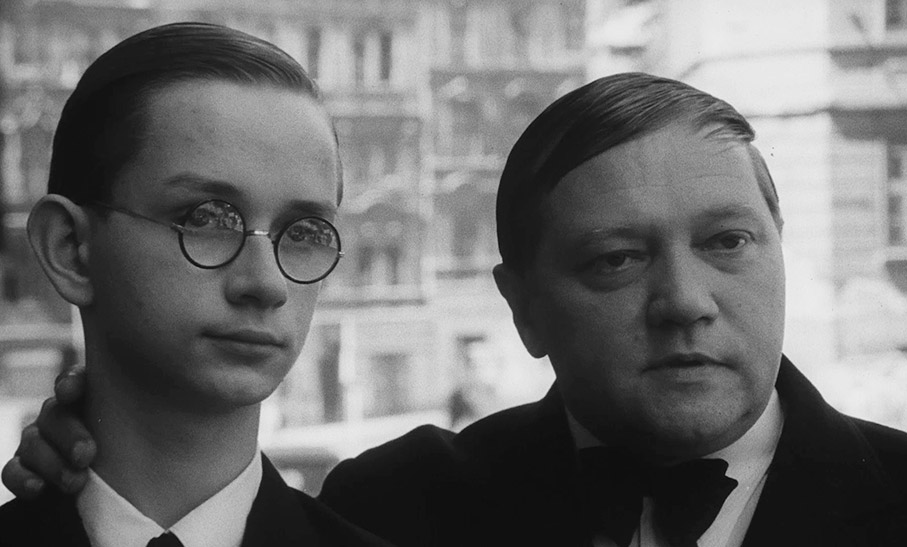

Crucial to why this works as well as it does is down in no small part to a beguiling and quietly unsettling lead performance from Rudolph Hrusínský, whose intermittently faltering, moon-faced friendliness makes his later actions seem all the more appalling. That he gets under your skin from an early stage, in spite of his cheery disposition, is partly down to the fact that his dialogue often sounds more like narration, a close-to-the-mic voice that softly trickles his philosophy directly into our ears. There's also something inherently creepy about his affection for the bodies of the recently departed, whom he treats almost like family, a connection neatly established through his autonomic habit of running a comb through his hair after tenderly doing likewise to a cadaver or even one of his children.

As Karl becomes seduced by the political dark side, the film moves into more openly metaphorical territory and Karl himself becomes a walking symbol of capitulation, betrayal and the dreadful and destructive nature of Nazi ideology. A second viewing reveals how smartly this downward spiral into murderous madness has been signposted, from the killings being portrayed by waxwork animatronics (actually actors in make-up, giving the show a particularly macabre feel) to the iron bar that Dvorak trips over and Karl requests be replaced because "it may come in useful." Given Karl's profession, there's a terrible inevitability to what his role within the party will eventually be, but even I wasn't prepared for the moment when his fascination with the Tibetan Book of the Dead would install in him the belief that he is the reincarnation of Buddha.

By any measurement, The Cremator is extraordinary cinema, a stylistically thrilling work that effortlessly melds narrative, character and socio-political subtext to increasingly disturbing but compelling effect. Even the blackly comic elements are seamlessly blended into the layered whole, typified by the comically bickering couple who disrupt almost every public gathering but whose eventual break-up leaves the abandoned husband in despair, a subtle but poignant reflection of the change that his country is undergoing. In politics, just as in life, you sometimes don't appreciate what you've got until it's gone.

As far as I'm aware, this is the first film previously released on DVD by Second Run to get a Blu-ray upgrade and it's a worthy one. Yes, there are still quite a few dust spots present and the occasional, single-frame flash of detectable damage, but in all other respects this is a serious upgrade on its already decent standard definition predecessor, with considerably (and consistently) sharper detail and an even richer tonal range to its monochrome imagery. Dust speckles aside, this is a very fine transfer that does cinematographer Stanislav Milota's work here proud.

The Linear PCM 2.0 mono soundtrack has also been restored, and while the dynamic range is as narrow as you'd expect for a film of this vintage (there's no thumping bass here), the dialogue is all clear and Zdenek Liska's lively score is nicely handled. There's also no trace of any former damage or rough edges.

Fluent Czech speakers will doubtless be pleased to know that the clearly rendered English subtitles can be switched off if preferred.

Filmed Introduction by the Quay Brothers (12:22)

The only on-disc extra carried over from the earlier DVD finds the always engaging Quay Brothers (you surely don't need me to explain who they are, do you?) enthusing about the film and ticking off nearly all of the points I'd made a note to include in my review. They even manage to top anything I was planning to say by describing the film as "visual and aural morphine" and some of the imagery as "like daggers to the eye."

The Junk Shop [Sberné sorovosti, 1965] (31:37)

Director Juraj Herz's first film may only run for 31 minutes, but it's still bristling with ideas and cinematic invention – watching this back in 1965, you'd have had little doubt that this man had a serious filmmaking future. The Junk Shop observes a single day in the colourful life of the establishment of the title, one based primarily around cheerful employee Haňta and his boss, Bohouš, and their interaction with primarily female customers, almost all of whom are trading in bundles of paper for cash or a lottery ticket. Many of these encounters are comical in nature, from the woman desperately searching for a mislaid invoice in the shop's mountain of waste paper – in which she subsequently loses her young son – to the former circus performer (clearly played by an unshaven male actor in drag) who demands a premium price for her old love letters due to the quality of their content. Briskly paced and consistently imaginative, it's tremendous and playful fun, from its almost Buñuelian disrespect for religion, to Bohouš's dreamy picturing of the flirty woman upstairs as the subject in a series of famous portrait paintings. There's so much going on here that I could fill a few pages describing the action and the comical layering, but it's best to just sit down and experience it for yourself. A terrific inclusion that despite a fair few dust spots and some small remaining damage, is in surprisingly good shape.

Audio Commentary with Kat Ellinger

The venerable Kat Ellinger – she of Diabolique magazine and The Daughters of Darkness podcast – is fast becoming the go-to authority on horror-themed works, at least for a number of our favourite distributors. The Cremator is one of her favourite films, and over the course of its 95-minute length she delivers a lorry-load of information on the film, director Juraj Herz, the Czech New Wave, author of the original novel, Ladislav Fuks, and more. It's fascinating and educational – I not only learned a lot, but have also added a number of films I was not even aware of onto my Must-See list. I've no doubt that Ellinger had some prompt notes to hand (at one point she does read out a quote), but for the most part this feels pleasingly off-the-cuff, driven by her passion for the film and her seemingly encyclopaedic knowledge of Czech and gothic horror cinema.

The Projection Booth Podcast with Mike White and Samm Deighan

Playing as a non-screen-specific second commentary, this detailed discussion of the film from The Projection Booth podcast – which, a little surprisingly, runs for the exact length of the film itself – has almost no crossover with Kat Ellinger's contribution but is every bit as enthralling. Subjects covered including the lead character's almost constant stream of dialogue, the use of the fisheye lens, the political undertones, the editing and inventive scene transitions, and a whole lot more. Lead player Rudolf Hrusínský is intriguingly compared to Peter Lorre, the importance of leaflets within the film is highlighted, and a connection is even found to Twin Peaks. It's fascinating stuff, delivered with a shared and very genuine passion for the film itself.

Also included is the expected Booklet, the meat of which is a detailed and authoritative essay on the film by Daniel Bird, whose detailed knowledge of the Eastern European perceptive analytical skills make this a compelling and revealing read. Credits for the film and production stills are also on board.

I fell in love with The Cremator on my very first viewing of Second Run's original DVD release back in 2012, and watching it again in crisp 1080p only served to highlight what makes this film so special. I've cheated a bit here by effectively reposting (with minor updates) my original review of the film itself, but with personal issues currently impacting on my free time and so much of the analysis that I could have added covered in more depth and with more authority by the extras on this disc, it seemed the right move, and I stand by everything I've written there. If you've never seen this film, then you're in for a dark and inventive treat, but even if you do have the earlier DVD, I'd consider this release an essential upgrade, for the considerable improvement in the image quality and the newly added and consistently excellent special features. Highly recommended.

|