|

I’ve stated before – probably several times now – that I have a particular fondness for films that eschew traditional establishing shots and open instead on a facial close-up, which can sometimes tell us something about the character or situation in which they find themselves before a word is spoken. The one that greets us in the first shot of the 1976 Mr. Klein poses a whole series of questions that anyone who knows their twentieth century history should quickly be able to answer. This face here belongs to a middle-aged woman who we soon realise is standing naked and embarrassingly trying to cover her modesty. Two hands are forcefully probing and manipulating her mouth in order to examine her teeth and gums, then move on to her jawline and cheeks. “Rounded gums,” a dispassionate male voice says, followed by, “Slight prognathism.” We then see the face of the doctor carrying out this examination, just before he moves on to measuring the spacing of the woman’s nostrils with a metal instrument seemingly created for this purpose. He continues to probe and measure all aspects of her face and head with what feels like an unnecessary and uncaring level of roughness, then has the woman walk naked across the room to comment on her thighs and her lack of instep. The whole thing is genuinely uncomfortable to watch. Then comes the line we’ve been anticipating. “Facial expression more or less Jewish,” notes the doctor dispassionately, although this is curiously followed by, “Attitudes during examination not Jewish,” whatever the hell he thinks that means. His conclusion, dictated to the nurse as the woman anxiously dresses behind a screen, is that the woman may have either Jewish, Armenian or Arabic ancestry and that her case is “inconclusive.” She is then allowed to leave, and as a final indignity is required to pay 25 Francs for the privilege of being examined to see if she belongs to a race that in occupied France in 1942 was becoming increasingly dangerous to be even be associated with.

It's after this that we meet the titular Robert Klein (Alain Delon), as he plays superficially genial host to a Jewish visitor (I wish I could be sure who the actor is here, because he’s really good) in the spacious study of his luxury apartment. The man has come to Robert to ask if he is interested in buying a valuable painting, one the man is attached to but is forced to sell because he plans to leave the country and needs the money. As a successful art dealer, Robert is certainly willing to purchase the work, but only offers the man half of what he is asking for it, fully aware that he has has a considerable advantage here, one that the man is begrudgingly forced to accept. Tellingly, just after he has signed the receipt that Robert has him draw up, he asks Robert for a business card to pass onto his friends who are in a similar situation to him.

Then, just as the man is leaving, Robert notices that a newspaper on his doorstep that he assumes the man has dropped on his way in, but the man reveals that he still has his copy of what turns out to be the Jewish Information newsletter. When Robert examines the one on the doorstep, he discovers that it has been addressed to him. Not being either Jewish or a subscriber to this journal, he is just a little confused by what proves to be the first chink in Robert’s emotional armour and the seemingly protective wall that social privilege has built around him. For all his lack of empathy for his unfortunate clients, his immediate concern that he is on the mailing list for a Jewish publication confirms that he is all too well aware of the threat under which these people are living. Assuming that this is result of a clerical error, he makes an appointment to visit the office of the newsletter publisher. The administrator (Roland Bertin) is confused by this apparent mix-up, but is unable to check his subscriber list because it is currently in the hands of the Prefecture of Police, news that transforms Robert’s confusion into genuine alarm. He heads straight to the Pigalle police station to talk to the resident Inspector (Michel Aumont), who discovers that the address on the card bearing Robert’s name is not the one at which Robert resides, seemingly confirming Robert’s theory that there is another Robert Klein with whom he emphatically does not want to be confused. When the curious Robert asks for the other Klein’s address, the inspector calmly puts the card away. “What would you say if I gave yours to anyone who asked for it?” he quite reasonably responds. Robert, however, is unable to just let the matter drop and becomes increasingly determined to find and confront this second Robert Klein and put an end to this potentially dangerous confusion.

I find it surprisingly difficult to put into words just what it is about the 1976 Mr. Klein – a late-career feature from celebrated but criminally blacklisted director Joseph Losey – that I found so consistently compelling. That pace rarely alters, and there are no sudden bursts of action or scenes of nail-chewing tension, and I’m not sure that Robert himself ever becomes a particularly likeable character. That I came to care about his fate nonetheless is down as much to Losey’s considerable skill as a pure filmmaker as it to Alain Delon’s perfectly pitched central performance and the knowledge of just how serious the implications of being identified as Jewish in Vichy France at that time were already proving to be. Yet to understand why the film exerts such an unwavering grip you need look no further than that opening sequence, one that tells you so much with so little in what is as impressive an example of understated cinematic storytelling as I’ve seen all year. It’s an approach employed and maintained for the entirety of the film’s two-hour running time, one that not only respects the intelligence of the audience, but that also allows Losey to impart information on a character, a setting or an event on more than one level simultaneously. When we first meet Robert, for example, we do so initially though his voice alone, heard from an upstairs room as he invites his guest in and begins negotiating an unfair price. The camera, meanwhile, lingers on Robert’s attractive young girlfriend, Janine (Juliet Berto), as she lazily wakes and saunters into an opulently luxurious bathroom to freshen her lipstick. Only when Robert appears and playfully chases her back to bed so that he can collect a secreted pouch of coins do we get to see his face. It’s a sequence in which the privileged life that Robert leads is captured by the visuals as the soundtrack clues us in to just how this lifestyle has been paid for. As the subsequent sequence in the study unfolds, no overt statements are made about who the visitor is, why he plans leave the city or why he would accept such a poor deal to do so quickly, but you would have be completely ignorant of twentieth century history not to work this out for yourself. Losey and screenwriter Franco Solinas (in collaboration Fernando Morandi) understand this, and are thus able to tell us all we need to know without saying anything out loud.

What unfolds is a quietly riveting blend of drama, character study, mystery, detective story and sobering true-life history, run though with a strain of Kafkaesque paranoia and even an occasional light dusting of surrealism. As Robert becomes increasingly obsessed with tracking down his mysterious doppelganger, the film remains teasingly ambiguous about the man’s true identity and at times whether he even exists. If he does, then he seems to have the same build as Robert and even something of his dress sense, first confirmed when Robert arrives at the location of a hellhole of an apartment that his doppelganger rented and is immediately mistaken for him by the landlady. In a particularly unfortunate bit of timing, she does so whilst in the process of being interviewed by the police about this absent tenant, police who will later show up at Robert’s home. Later in the story, Robert is at a busy restaurant with his good friend and lawyer, Pierre (Michel Lonsdale), when a bellboy begins walking the floor calling out his name, something the now more cautious Robert initially chooses to ignore. When he does respond, the bellboy reveals that he was asked to locate him by a man at the bar, one who looked similar to Robert but has now disappeared. Robert then spins round to look for the man and catches his own reflection in a large wall mirror, an extraordinary moment that is framed in such a way that, just for a moment I was convinced – as I suspect Robert also was – that he was looking at his exact double in the flesh.

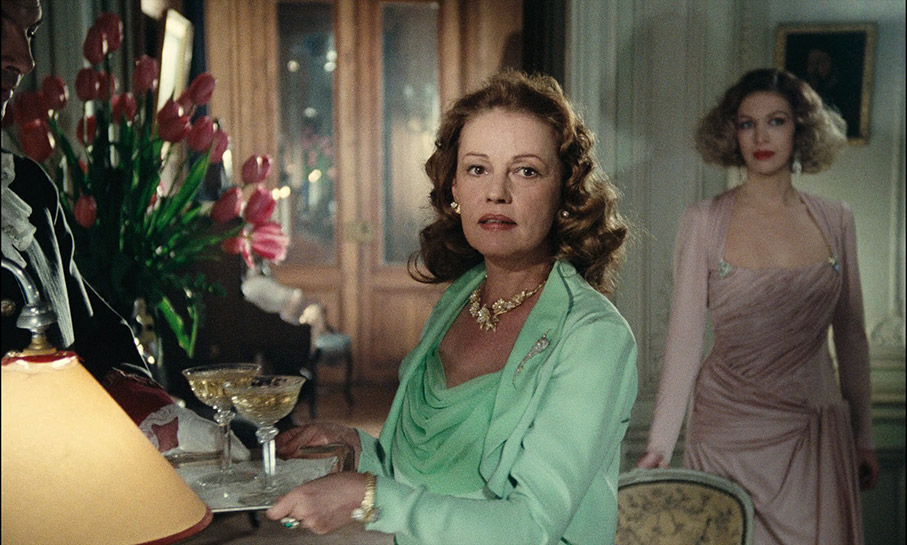

At one point, his quest leads Robert to castle in which an aristocratic dinner party is being hosted by the well-to-do Charles–Xavier (Massimo Girotti), whose wife, Florence (Jeanne Moreau), has been having an affair with Robert’s doppelganger behind her husband’s back. Adding a layer of curiosity to this latest piece of the jigsaw puzzle is that a letter sent by Florence to his doppelganger was delivered to Robert’s apartment instead. Given that Florence was not even aware of our Robert’s existence, the question of how a note sentto her lover could have been posted instead through Robert’s door remains teasingly unanswered. Although one clue always seems to lead to another, at no point does it feel as if Robert is getting any closer to solving the mystery that has come to consume him. Increasingly, it also seems at risk of destroying him, notably when he completely disregards his own safety to walk back into a danger from which he has just fled in order to chase a new lead, and which later sees him abandon all reason in pursuit of an answer that logic suggests he may still never find.

Constantly hovering in the background is the growing threat to the city’s Jewish population, intermittently signposted by police preparation for an as-yet unspecified operation, and more directly by the visits paid to Robert by detectives unaware that he is not the man for whom they are searching. The whole thing builds to a climactic sequence of almost documentary realism, one that recreates the notorious Vel’ d’Hiv roundup in which over 13,000 Jews were arrested and handed over to the occupying German Army for transportation to extermination camps. It’s an inglorious episode of French history that Mr. Klein was one of the first films to honestly portray, while the scale of the operation is soberingly captured by tracking shots along fencing of the Vélodrome d'Hiver in which hundreds of the arrestees are being herded and handheld footage of distressed adults being separated from their children and spouses on arrival.

There is so much more I could talk about when discussing this extraordinary film, a detailed scene-by-scene analysis of which would provide me with enough material for a weighty reference book. Although directed by a politically self-exiled American who apparently didn’t speak a word of French, it is widely regarded in the country in which it was made as one of the finest and most important French films of the 1970s. Handsomely shot by British cinematographer Gerry Fisher, it’s impressively performed across the board by a stellar cast, and is a showcase for the sometimes undervalued talent of a superbly restrained Alain Delon, for whose production company the film was made. Others may disagree, but for me, this is one of the finest achievement of a director that I’m coming to realise, as I make my way too slowly through the films he made over the course of his troubled but often remarkable career, was one of the most important and talented filmmakers of his day.

Sourced from a new 4K restoration by Hiventy with the support of Centre National du Cinéma, the 1.66:1 transfer on this StudioCanal Blu-ray boasts impressive sharpness and picture detail and has that pleasingly textured look you still seem to only get with features that were originated on 35mm film. The colour sometimes has a warm and earthy hue, but elsewhere leans towards cooler blue-greys, but on the whole the pastel-leaning pallete is very nicely captured, all of which gives the film a subtle and effective period feel. The contrast is decently balanced, though the always-solid blacks are accompanied by some loss of detail in darker areas, though once again I cannot be sure how much of this is deliberate. The image is clean of dust and damage and sits rock-solidly in frame.

The DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0 soundtrack is always clear and has a decent dynamic range without a trace of wear or damage. I can’t confirm whether the track is mono or stereo, but using headphones I was unable to detect any clear separation so tend to suspect the former. A German dub is also available as a DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0 track, which has clear dialogue but a more aggressive mix of the location sound, which is sometimes louder and reproduced with less finesse than on the French original.

Optional English and German subtitles are available, plus French subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired. When you select from these three languages on loading the disc, the appropriate subtitles are selected by default if you choose German or English (the French SDH subtitles require selection), and the menus also appear in the selected language.

Introduction by Jean-Baptiste Thoret (11:23)

Critic Jean-Baptiste Thoret delivers a busy introduction to the film and speaks at the sort of speed that will keep the eyes of anyone not fluent in French firmly glued to the subtitles. He gives a flavour of the high regard in which the film is held by French critics by describing it both as “a masterpiece” and “a perfect film from beginning to end,” and the praise doesn’t end there. He highlights the links to Marcel Ophüls’ 1969 documentary, The Sorrow and the Pity, as well as to the plot of Alfred Hitchcock’s North By Northwest, and provides a detailed overview and partial analysis of the film without hitting us with significant spoilers. There is also the option to watch this before the film itself when you select Play Film.

Mr. Klein Revisited by Michel Ciment (46:43)

Revered critic and editor of the cinema magazine Positif, Michel Ciment, talks at considerable length about a film he clearly also holds in the highest regard. A lot of ground is covered here, including background details on Joseph Losey and a passionate assessment of his contribution to cinema and his work on Mr Klein, aspects of which are dissected and analysed in almost forensic detail.

Interview with Henri Henri Lanoë (25:07)

One of three credited editors on the film remembers being offered the chance to work with Joseph Losey by Alain Delon, and describes it as the most satisfying film on which he worked in his long career. Having lived in German-occupied France as a child, he salutes the accuracy of Losey’s recreation, and reveals that the director struggled with the way that films were edited and mixed in French cinema at the time. He also recalls that Losey liked the diegetic songs he had used as placeholder music so much that he decided to keep them, which left Italian composer Egisto Macchi with very little to do.

A film I was criminally unfamiliar with until I was gently prodded to take this disc for review, and I’m now so glad that I agreed to do so. Mr. Klein is one of those special films that I almost feel was made specifically for me, as it gives me everything I want from a low-key drama and does it with the sort of style and layering of scenes that enables me to get more out of the film with every viewing. The special features reinforce the fact that I’m not alone in my deep admiration, and although the black levels punch above their weight a bit, this is still a fine restoration and transfer, and the disc thus has to come enthusiastically recommended.

|