| |

“A man and a woman together should be very happy. But they’re often connected by old conventional ties, as I tried to show in Eve and other films, outworn vows, outworn conventions in which nobody believes, which devalues them and which are unworkable. And they can only fight out, and there is nowhere to go. And when they can’t get out, they fight each other.” |

| |

Director Joseph Losey |

As a location, Venice seems to hold a particular fascination for filmmakers and has featured heavily in a good many films in a variety of genres, from Lone Scherfig’s romantic comedy-drama, Italian for Beginners, to Nicolas Roeg’s darkly haunting masterpiece, Don’t Look Now. I’ve only been there once and that was on a daytrip from the mainland in high season, when the city was so teaming with tourists (of which I was one, of course) that just to break through the throng to explore the quieter back streets and alleyways was a Herculean task. I left with a far better understanding of why so many Venetians detest this summer invasion.

Eve, a 1962 film by Josey Losey that I’ll admit straight up to never having seen before this new Indicator Blu-ray arrived at my door, was made before the city started sinking under the weight of package holiday tourism and opens on the titular Eve (Jeanne Moreau) and a male companion and as they travel through Venice in a covered motorboat. As the craft pulls up to the shore and Eve alights, the camera pulls back through a window and pans across the interior of small but busy bar, where patrons are being entertained by stories of his formative years by lively but heavy-drinking Welshman Tyvian Jones, who is described by one patron as “one of our Venetian characters, part-time writer, part-time guide and a couple of other things.” He’s in mid-flow when a man named Sergio Branco (a curiously uncredited Giorgio Albertazzi) walks into the bar, and the mere sight of him prompts Tyvian to freeze. When Sergio sternly asks if he remembers why they are there, Tyvian throws some money on the counter and hurriedly leaves. Outside he reacts as if he’s seen the mutilated ghost of a once-close friend, then walks off and starts to recall the events that brought him to where he is now.

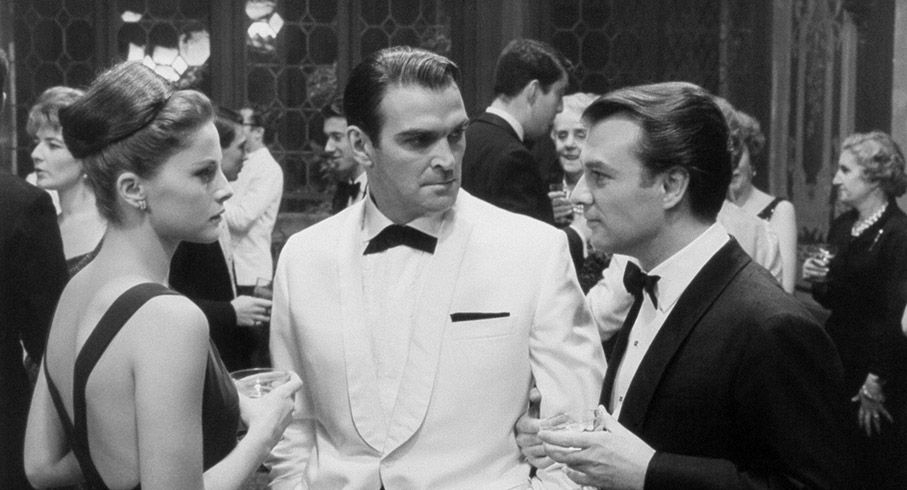

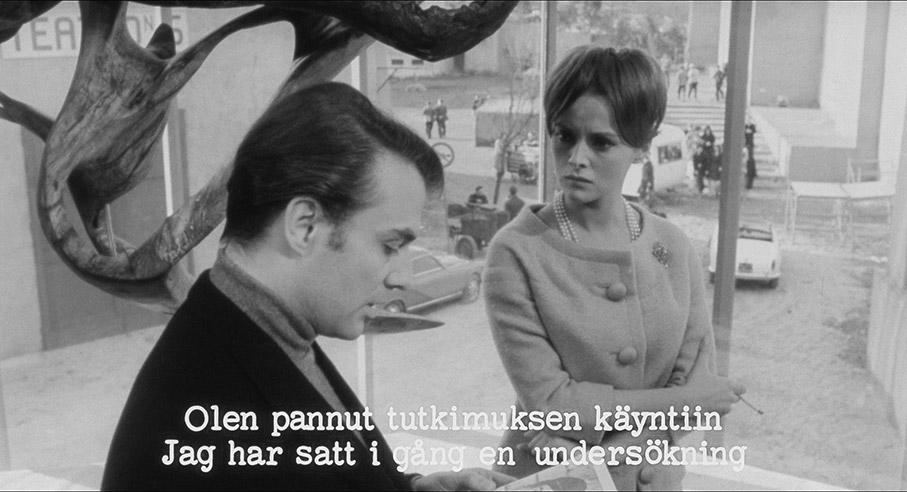

The film then hops back to a previous summer and the premiere of a film adaptation of Tyvian’s hugely successful first novel, The Stranger in Hell. As he explains in voiceover, “The book had made me famous. The film had made me rich.” At a post-premiere party held in one of the city’s grander buildings, a few things become very quickly evident. It turns out that Sergio was the director of this film adaptation, and he clearly has a thorny relationship with Tyvian, who is in engaged to Sergio’s loyal and attractive assistant Francesca (Virna Lisi). Francesca dotes on Tyvian and he does seem fond of her, though when a friend of theirs announces that the two may be marrying soon, the look on Tyvian’s face and his swift departure to a quiet balcony suggest that he’s not quite ready to tie that particular gordian knot. Even less happy about the prospect is Sergio, who is in love with Francesca and has little time for Tyvian, whose honesty he questions and whose background he is investigating. He nonetheless seems keen to make a film of Tyvian’s second novel, a book he has rented a house near Tocello in which to start writing, though a remark from Sergio suggesting that this work has been a long time coming clearly needles the author.

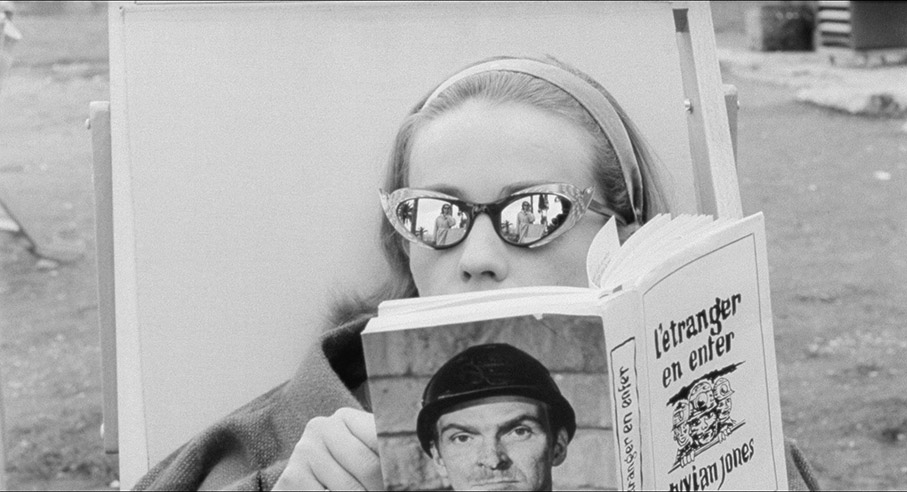

Outside the rain starts bucketing down, and Eve is once again on a small boat, this time with a man named Silvano Pieri (Checco Rissone). The storm becomes so impossible to navigate that they pull ashore and break into the only nearby house in order to shelter, and wouldn’t you know it, the building they’ve found themselves inside is the one that’s been rented by the as-yet unaware Tyvian. In the few short minutes of screen time that follows we glean crucial information about all three individuals, almost none of which is communicated through expositional dialogue. When Eve and Silvano enter a nicely kitted-out bedroom, for example, the nature of their relationship is exposed both by Silvano’s desperately eager-to-please submissiveness and Eve’s casual dispensing orders for and almost indifference to his presence. When Silvano humbly exits the bedroom, the camera stays locked onto Eve as she casually explores the room and puts a record of Billie Holiday’s Willow Weep for Me (which almost becomes her theme song) onto a portable player she presumably carries with her for this very purpose. She reveals whose house it is by examining multiple copies of Tyvian’s book, each seemingly in a different language, then takes a playful soak in a luxurious en-suite bath. When an outraged Tyvian arrives to find his home has been invaded, instead of focussing on his confrontation with Silvano, Losey stays locked on to Eve’s face, her expression clearly intimating that while she may she can hear the furious exchange taking place in the hallway, she’s not remotely bothered by it. When a still barking Tyvian enters the bedroom and angrily takes off the record, the apologetic Silvano in tow, Eve casually gets out of the bath, slips on a gown, walks into the bedroom and puts the record back on, then returns to the bathroom closing the door behind her. At no point does she even acknowledge either Tyvian or Silvano’s presence. Tyvian, on the other hand, is mesmerised by Eve from the moment he first sees her, and his intentions are made clear by his sudden change of attitude towards Silvano, whom he immediately stops berating and encourages to go downstairs and make himself a drink. He even invites the couple to stay the night and gives the still disinterested Eve his own bedroom, where she cuts short his attempts to charm her simply by opening the door to the bathroom, in which a framed picture of Francesca prominently sits. A short while later, when Tyvian’s designs on Eve become evident to Silvano, the two men end up fighting over her, first verbally and then physically, a brawl that ends with Tyvian throwing Silvano out. He then nips upstairs to try it on with Eve, who responds by braining him with a glass ashtray and taking her leave.

If it seems I’ve gone into unnecessary detail on this single scene, then I’ve done so partly to give a flavour of how so many scenes play out in this consistently layered and thematically complex film, with the way characters act and speak proving every bit as important as what they say. It’s a pivotal scene, laying the foundations for much of what will follow by establishing Tyvian’s fascination with Eve and the ease with which he’s willing to go behind Francesca’s back and chase another woman, as well as dropping strong hints about Eve, whose lack of interest in the love-sick Silvano borders on boredom, a seemingly default state when it comes to the men that are drawn to her. In the very next scene we’re given a clearer indication of her philosophy of life when we see her relaxing happily in her apartment, having her nails filed by her maid and surrounded by expensive gifts that were likely bought for her by men she has toyed with and then discarded. Two things quickly become clear, that Eve exploits these men to feed what could be seen as superficial pleasures, and that the smitten Tyvian remains determined to seduce her. It’s a calamitous match, one that is set to frustrate Tyvian and potentially wreck his life but that will do little to drastically alter the course chosen by Eve. It remains uncertain if she is someone who enjoys the finer things in life and has a natural gift for making the men she meets pay for them or is a high-class escort who sometimes enjoys a little fun on the side. At one point she concludes a cordial weekend with Tyvian at an expensive hotel by suddenly and stonily revealing that she now expects to be paid, adding that the real reason she came here with him (at his expense) was to win money at gambling and meet a couple of new clients. Then again, is she saying this to push Tyvian away because she feels he is taking their relationship too seriously, to keep him at a distance after he failed to take heed to her earlier advice not to fall in love with her? Your guess is a as good as mine.

On the basis of this setup Eve has the potential to be a bit of a slog, focussed as it is on two unsympathetic individuals and the emotional harm they inflict on themselves and those around them. Eve is on the surface a predatory user whose only interest in those she attracts and toys with is the material goods and services she extracts from them, while Tyvian is so shallow and delusional that he is willing to sacrifice all of the positive aspects of his life for an obsession that he’s unable or unwilling to see is self-destructive. Even before he first claps eyes on Eve he seems unsure about committing to his relationship with the good-hearted Francesca, but once the two meet he’s simply too weak to be honest with Francesca and clear the way for Sergio, instead keeping her in reserve as someone to fall back on when things don’t go as he’d hoped with Eve. Repeatedly we’re teased by the possibility that either Tyvian or Eve might have a moment of life-changing realisation, but every time this happens it is then undercut by the characters themselves in a manner that pushes a reset button on the nature of their relationship. There are times, for instance, when Eve seems to be genuinely warming to Tyvian and enjoying their time together, but even the most persuasive of these concludes with Eve flipping back to her cold and mercenary norm. Whether this is how she actually feels or is a wall that she throws up to prevent herself from becoming too deeply involved with a man she actually feels something for is open to question. Tyvian, on the other hand, is living a lie and refuses to take even sledgehammer hints, running back to Eve even after being delivered the cruellest of kiss-offs and willing to sacrifice long-held friendships to be at her beck and call. In one particularly sad display of desperation, he shows up at her apartment and pathetically pleads to through a gap in the chained doorway, while Eve cheerfully ignores him and her maid takes receipt of a gift from another of her male admirers thanking her for a fun weekend.

So what is it about the film that exerts such a hold? Initially, I found this hard to pin down. What I do know is that when I put this disc in my player, it was at a late hour on a day in which I was seriously under the weather, and I’d only planned to check out the opening few minutes to get a flavour of what was to come, then go to bed. I ended up watching the whole thing, unable to break away from it despite my tiredness and ill health, quickly and completely becoming as hooked by it as Tyvian is by Eve. A key reason for my instant engagement lay in the performances of Stanley Baker as Tyvian and Jeanne Moreau as Eve, both of whom are on riveting form here, both re-enforcing that long-held storytelling notion that characters don’t have to be particularly likeable to be interesting. Baker is a master of barely controlled frustration, and is able to radiate such a strong sense of will that when he’s reduced to begging Eve to see him the effect is genuinely uncomfortable to watch. Moreau, meanwhile, so radiates allure that it’s easy to see why men would fall for her, but she is equally persuasive in her intermittent disinterest in Tyvian and her air of contentment at the frivolous aspects of her chosen lifestyle. Director Losey marshals these elements with a command of the medium that initially swept me along – the way conversations move from person to person in the post-screening party is so seductive – and with a filmic economy that only really hit home on my second viewing. His facial close-ups of Moreau may theoretically play to his son Gavrick’s belief that the two were just a little bit in love with each other during the film’s making, but it feels only right that Eve should be so closely observed in the film that bears her name, and Moreau reveals so much about her character through her reaction to the words and actions of others and even her environment. Losey’s willingness to experiment is also evident throughout, in his sometimes unexpected camera placement, the economic use of time-compressing editing, a semi-hallucinatory sequence involving a nightclub dancer, and in the striking shot in which a dismayed Francesca is reflected in the lenses of sunglasses being worn by a reclining Eva as she reads Tyvian’s book. It’s a multi-layered image about which a small but significant essay could be written, one that could then be expanded into a discussion on the film’s use of mirrors and reflections to underscore its exploration of duality, a trait most evident in – but not confined to – the false image that Tyvian presents to the world to conceal the sad and insecure truth that lurks beneath.

When the film was first screened in its cut-down form (more on this below) it took a critical mauling, one of the key complaints being that the true motivations for Eve’s behaviour remain frustratingly unclear. For me, that ambiguity is one of the things that makes this film so fascinating, open as it is to so many interpretations. Is she just a cold-hearted shrew who exploits her sex appeal in the shallow pursuit of money and ultimately functionless material goods? Maybe. Is she a woman who has been so hurt by the opposite sex that she has chosen to punish any man who dares pursue her? Perhaps, though there are clear hints that not all those she dates are unhappy with the way that she treats them. Is she a metaphoric avenging angel sent to earth to torture Tyvian for past sins? It’s certainly one reading favoured by Losey’s son Gavrick. Is she a high-class reworking of the prostitute in James Handley Chase’s source novel, one who extracts payment from her clients via indirect means? It’s a possibility. Is she an emotionally damaged woman hiding behind an attachment to superficial objects and experiences? If so, then this paints her playful torture of Tyvian in a very different light. Or is she, as Gavrick also suggests, a reflection of Losey’s response to his wife’s affairs and the impact they had on his feelings for her? If so, then what does that say about Losey himself as reflected in Tyvian’s weaknesses and desperation? I could go on.

Eve is also a visually arresting film, thanks in no small part to the gorgeous monochrome compositions and lighting of master cinematographer Gianni Di Venanzo (he of Michelangelo Antonioni’s La notte, Federico Fellini’s 8½ and Francesco Rosi’s Hands Over the City, to name but three) and Losey’s eye for expressive and offbeat camera placement, whether it be the almost top-shot view of Tyvian as he is refused entry to a laughing Eve’s apartment, or the low-angle wide of a pre-gathering for the wedding of in-film screenwriter Alan McCormick (James Villiers). Most effective of all are his probing close-ups of Eve and Tyvian, which catch small inflections that tell you as much about the characters as anything they say. Just watch Jeanne Moreau during the pre-title boat ride as her expression flicks between warm smiles at her companion and looks of uncertainty, disinterest and even shuddered discomfort at an unspecified memory in the space of a few seconds – see the film a second time and you’ll find plenty to read into this moment. In my humble view, it all works sublimely. Yes, we will likely never see Losey’s original 155 minute cut now and I can guarantee that some will find the find the characters annoying and the film itself unsatisfying, whatever version they elect to watch. I am not one of those people. For me, Eve is a film that challenges and confronts and boldly refuses to offer easy answers or comfortable resolutions, one that explores the (self-) destructive nature of obsession and rejects the idealisation of relationships that still tends to prevail in mainstream cinema. It’s as thematically and cinematically arresting as any film I’ve watched so far this year, and as evidence of Losey’s importance as a filmmaker, storyteller and artist, Eve is up there with his finest work.

Before I get started here I think it only fair to note that much of the text in this section has been lifted from the version comparison feature on the disc titled The Many Faces of Eve, which does such a clear job of explaining the different cuts that I had little to add to it. I’m reproducing – or perhaps adapting – it here to give those thinking of buying this disc a clearer idea of what they will be getting and why.

Anyway, as you’ll find mentioned many times in the special features, Eve was subjected to a number of recuts following its completion, and a total of three separate versions have been included here, one also with the option of an extended ending. Losey’s original cut, the one submitted to the Venice Film Festival, ran for 155 minutes, but was never shown to the public and sadly no longer exists. Its scheduled festival screenings were cancelled by producers Robert and Raymond Hakim, who claimed that their French distribution deal would be harmed if this cut was shown at the festival, which tells you all you need to know about what they thought of it.

After an unsuccessful private screening of the original cut, Losey was persuaded by Jean Moreau to edit it down to 135 minutes, which is the last version that met with Losey’s personal approval. Unfortunately, it wasn’t to end there. The producers then made further cuts, this time to the original negative, reducing the running time further to 116 minutes, which premiered in Paris and was a critical disaster. Further cuts were made and the running time was reduced to 109 minutes for a European version that was released as Eva, and 108 minutes for a US release under the tacky title of The Devil’s Woman. Structurally, Eva and The Devil’s Woman are broadly similar, but while the Italian dialogue has been retained on The Devil’s Woman, the voices have been redubbed in English on Eva, and even when those same characters converse in English their voices have been redubbed for continuity (Sergio’s redubbed voice in particular just doesn’t sound right here). When he saw the Eva cut, Losey described it as “a common, tawdry little melodrama, unclear, pretentious, without rhythm and taste.” He later discovered that his 135 minute edit had been sold to a Scandinavian distributor, but by the time he had raised the money to buy a 35mm print, this version had been cut by 15 minutes and had unremovable Finnish and Swedish subtitles.

When you elect to play the film you are offered four options:

Play as Eve (126 mins), the most complete available restoration available of the film, one that includes two entire scenes that survive only in the Scandinavian version and thus have Finnish and Swedish subtitled burned in, plus other sequences and shots being made available for public viewing for the first time. This version has been restored to be as close as possible to Losey’s preferred cut and is the one reviewed above. The aspect ratio is 1.85:1.

Play as Eve (126 mins), the same restoration but with an extended ending.

Play as Eva (109 mins), the European release cut with the Italian speaking characters redubbed. This version was sourced from an HD master supplied by StudioCanal and is framed 1.66:1.

Play as The Devil’s Woman (108 mins), the American release cut with the original mix of English and Italian dialogue. This version was also sourced from an HD master supplied by StudioCanal and is again framed 1.66:1.

A quick flick through the special features or even a read-though of the above will give you a flavour of the mountainous obstacles that anyone attempting to restore the film faced, but Amsterdam-based EYE Filmmuseum bravely took it on anyway. With material drawn from multiple sources and some of it only surviving on a single print, inevitably there is going to be some variation in quality, but all things considered this is still an impressive job. The best material is in excellent shape, with sharply defined detail, a generous contrast range and solid black levels, all of which shines in some of the facial close-ups, and much of the restoration is of this or similar quality. A few shots drawn from less ideal source material are a tad softer, and some sequences do still have scratches and minor water damage (this is usually on the frame edges) that presumably would have been impossible to remove without harming the integrity of the image. It’s a similar story for the two scenes rescued in their entirety from the Scandinavian print, whose Swedish and Finnish subtitles are simply too large to have been digitally removed without doing visible harm to the image on which they are imprinted. Considering these scenes have been missing from UK and US prints since the film’s release and we wouldn’t be seeing them otherwise, this is easy to live with. A fine film grain is visible and there is no evidence of digital image enhancement.

The DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0 mono soundtrack is in solid shape, being free of obvious damage and wear. Although there are some inevitable restrictions in the dynamic range, the dialogue is always clear, while Michel Legrand’s jazz-driven score and a few of the sound effects intermittently seem to stretch beyond these sonic limitations.

Two sets of optional English subtitles are available. The ones that kick on by default provide translations of the Italian dialogue only, and these can be switched off if you’re fluent in the language. Alternatively, there are the expected subtitles for the hearing impaired, which as well as translating the Italian dialogue also handily indicate when Italian is being spoken.

Joseph Losey: Other Places (8:33)

An interview with Josey Losey, conducted for French television and originally broadcast on 26 January 1967 under the title Cinéma: Le Cinéaste Josey Losey fair un tour d’horizon (à Londres), in which he talks briefly about his move to England after being blacklisted in Hollywood, his interest in stories of non-conformists and, of course, Eve, of which there are several extracts. It also includes a few choice quotes (one of which appears at the top of this review), a personal favourite being, “You don’t have to be an outcast to talk about those who are outcasts,” and Losey makes a telling comment on cut-down version of the film when he says, “I think that Eve is the most personal of my films, the most subjective, but it’s also, for many reasons, the most incomplete film.” Losey speaks in English, but his voice is almost drowned out by the spoken French translation, which has then been translated back into English by optional subtitles that kick on by default.

Jeanne Moreau: Appetite for Destruction (4:44)

Another brief but valuable French television piece, whose mouthful of a title was Tête d-affiche: Jeanne Moreau ou la saveur de vivre and which was originally broadcast on 30 January 1972. When questioned on it, Moreau dismisses the notion that the characters she plays are in any way ‘vicious’ and suggests that such a view is the result of narrow-minded and hypocritical people who use the term to describe anything they find unusual. I’m with her on that. She talks about being attracted to roles that cannot be easily categorised as simply good or evil, and when asked if there are times when she says that she could have been Eve (who is called Eva here), she pauses briefly for thought and then replies with a smile, “Yes, but I don’t say it for long.”

The BEHP Interview with Reginald Beck (124:31)

Another of the valuable audio recordings made for the British Entertainment History Project that are now appearing regularly on Indicator discs (another bloody good reason for buying them, I’d say), this one is with Joseph Losey’s regular editor Reginald Beck and was conducted by Alan Lawson and Winston Ryder on 22 July 1987. Beck was 85 at the time of recording and was clearly not in the best of health (I detected breathing difficulties early on), but his long history in the industry nonetheless makes for a fascinating listen. Although he speaks with a middle-class British accent, Beck was actually born in Russia and emigrated to the UK with his family as a child and first joined the film industry during the silent era. As ever, part of the appeal here is hearing the interviewee’s honest opinions on the sometimes notable filmmakers that he or she has worked with, and Beck doesn’t disappoint on this score. Carol Reed he describes as someone who could never make up his mind (“I’ve no patience with people like that”), Anthony Asquith as a marvellous man to work with, Herbert Wilcox as more an impresario than a director, and when Alberto Cavalcanti’s name is mentioned, Beck lets out a weary, “oh dear, oh dear” and admits that he didn’t like him or enjoy working with him. Of course, his long-standing working relationship with Losey gets some coverage, though is not examined in the sort of detail that I was hoping for. When Eve comes up, Beck laments the recutting of what he remembers as one of Losey’s best. There’s plenty more here, including discussions on editing equipment and recollections of his film work during World War II.

Gavrick Losey: All About Eve (18:57)

Joseph Losey’s son Gavrick looks back at what he regards as a very strange picture that he suspects was partly about his father’s relationship with his mother. There’s an interesting story with a literal punchline regarding work he did for editor Reginald Beck on the film that was messed about by producer interference, and another about Jeanne Moreau really getting into character off set by teasing Stanley Baker and then balling him out. He praises the film’s cinematography and laments the fact that almost no-one has seen his father’s original cut, and describes the release version, a little unfairly, as “an uncompleted, messed-about work on the journey to The Servant.”

Neil Sinyard: A Creation Myth (23:31)

Author, film scholar and Indicator regular Neil Sinyard reflects on a film he feels falls into the category of ‘mutilated masterpieces’ and which he sees as a modern take on the Adam and Eve myth. He looks at how the project came about and how it fell victim to a series of changes demanded by the producers, and cannily notes that making cuts to a film doesn’t necessarily make it feel shorter, as doing so can disrupt the editing rhythm, a point on which I heartily agree. He reveals that Losey’s original plan was to have the film’s male/female conversational dynamic reflected in a soundtrack on which Billie Holliday tracks were augmented by a Miles Davis score, an intriguing proposal that was nixed by a combination of rights issues and an unwillingness on the part of the producers to cough up for Davis’s fee. As it happens, Losey was apparently happy with the score written by Michel Legrand but dismayed by the subsequent changes made to his musical cues. There’s some speculation on Eve’s motivations that I found myself sharing, and Sinyard intriguingly finds thematic links to Nicolas Roeg’s later Bad Timing, which I now feel the urge to watch again as a result.

The Many Faces of Eve (15:45)

A most welcome and clearly presented breakdown of the three main cuts of the film included on this disc, which is captioned with textual explanations that I have borrowed heavily from for The Alternative Cuts section above and which includes side-by-side comparisons to illustrate the changes made. Unless you really know the film off by heart this is an invaluable guide to the differences between the various versions and the importance to the character development of the material that has been restored.

UK Theatrical Trailer (3:32)

A trailer that decides from the start to toss any ambiguity regarding Eve’s motives to the four winds by loudly proclaiming that she’s on a revenge kick to punish men for ruining her. It also makes Jeanne Moreau its primary focus and gives her British co-star only a passing mention. As is suggested by the on-screen text and confirmed by the following extra, this is actually the French trailer with an English language narration. As trailers go, it’s structurally plodding, with two scenes playing out almost in full.

French Theatrical Trailer (3:32)

Exactly the same trailer but with the original French narration, a little less emphasis on Moreau but still the inference that Eve is out for revenge for the past sins of men.

Image Gallery

36 screens of promotional stills and posters, all of which have the film titled as Eva.

Booklet

Following the credits, there is an engaging essay on Jeanne Moreau and her titular role in Eve by freelance film critic Phuong Le. Next there are quotes from various interviews with Josey Losey in which he talks about how he came to the project, working with Jeanne Moreau and Stanley Baker, the film’s intended use of music, the changes made by producers Robert and Raymond Hakim, and more. Following this, we have a short but useful piece on the source novel by James Hadley Chase comprised mainly of telling extracts from the book. After this are excerpts from three contemporary reviews – the one from Monthly Film Bulletin expresses disappointment, the one from Cahiers du cinema sings the film’s praises, and a third from Films and Filming defends it against charges of ‘Antonioni-ism’, which I have indeed seen the film falsely accused of. Bringing up the rear is a fascinating piece on the film’s restoration by Simona Monizza, a curator and restorer at EYE Filmmuseum. Information on the transfer, stills and poster reproductions have also been included.

A film about two unsympathetic individuals, one of whom brings about the downfall of the other, should not theoretically make for compelling cinema, especially in a film that has been repeatedly altered from the director’s original vision, but evidence to the contrary is all here for those receptive to it. As ever, Eve won’t work for everyone and I do get that, but I was riveted by it from the opening scenes and it just seems to get better with every viewing. I’m not alone here. When fellow site reviewer Jerry Whyte, who due to what was doubtless a fluke of bad timing missed the news story announcing this release, heard that my review was almost complete and that he had thus missed the chance to snag the job of writing about it from me, he was metaphorically banging his head on the table, revealing that it’s his favourite Joseph Losey film and one that he assures me he’d have bitten my hand off to review. Frankly, I’d love to see what he’d have written. If you’re even half as passionate about the film as we are, then this Indicator Blu-ray is a dream come true, containing four cuts of the film (well, technically three with an additional end scene for one), including the most complete version in existence, which has been carefully restored, and all backed up by a slew of excellent special features. A knockout release that comes highly recommended.

|