| |

"You're not respecting the law this way. In fact, you're using your majority power to defy the law. Two very grave facts have emerged. First, public land was sold to a private citizen. What might have been built there? A park, a school, a hospital? Secondly, the council at large was never informed, which is inadmissible when public interests are at stake. Only the opposition can act as a check on the majority's power, and that's the only guarantee of democracy." |

| |

Councilman Balsamo |

| |

"Now we're getting somewhere. Compliance is only verified after an incident. Each department did its job. Let people die." |

| |

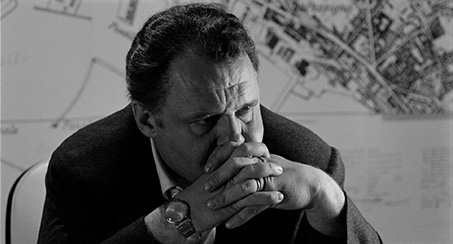

Councilman De Vita |

If the idea of self-serving property developers – ones who put profit above the welfare of those who end up living in the houses they throw up as cheaply as they can – sounds like something from the bad old days of tower blocks and corrupt councillors, let me tell you a little story about the properties currently being constructed not far from my back door.

Having had their first three proposals rejected (a story in itself, but not one for here), the developers reached a compromise that involved wedging a row of narrow terraced houses against a railway embankment. Due to ongoing wrangles about just how many properties they can squeeze into this space, the build has taken some time and was in progress for a good six months before the roofs were finally fitted. During this period the wood and plasterboard interiors were subjected to a half-year long assault of heavy rain showers and blazing sunshine. No problems there. Wood just loves being made wet and then rapidly dried out over and over again. In order to cram as much real estate as possible into a small space, none of the houses have doors or windows at the rear, and there is thus no escape route in the event of a fire at the front of the properties. Ah. This also makes it nigh-on impossible to create a through draft in the summer. And they'll need one, believe me. With no rear windows, it was decided that the only way to get any natural light to the rear of the houses was to fit some really big windows at the front. And being south facing, these windows will be hit by the summer sun all day long. Keep that in mind while I relate what happened next.

Despite only having planning approval for big windows for the first floor bedrooms, the developers decided they'd fit patio doors with Juliet balconies instead (you know the sort of thing, those railings they put in front of such high doorways to stop you falling out). The trouble is that they ordered the wrong doors, ones that open outwards instead of inwards as required. Putting right this mistake would cost a few thousand, so they elected instead to leave them in place. And obviously you can't fit Juliet balconies in front of outward opening doors. Think about this for a second. A first floor bedroom with doors that open outwards and no barrier to stop you walking through them. Our local council, as is its way, hardly raised an eyebrow. The developer's solution to this health and safety nightmare (one enforced by the planning office, I should add) was to have stays fitted to prevent the doors from opening too far. Just far enough for a small child or a dog to get through, perhaps. Given how hot the interiors of these houses will be once the summer sun hits that glass, I'm guessing that the first thing any future resident will do is unscrew the stays so they can open the doors more widely and get some air into the room. I certainly would if I moved in there. The council, meanwhile, after some haranguing from local residents, eventually noticed that these doors were actually supposed to be windows and insisted they be changed. The developer ignored them and began preparations instead to pull down a local landmark situated on the land without bothering with things like official approval. Of course, it's probably sheer coincidence that a close relative of the head of the development company is reputed to be good friends with... No, at this stage it's probably best that I say no more.

And there's so much more I could tell you about this almost blackly comic tale of incompetence and self-interest, one coloured by a startling lack of concern for the possible consequences of this collision of greed and toothless inaction. The council's reluctance to take measures that could prevent a potential serious injury or even a death has everyone bemused, including some of those involved in the build. Yet should that death occur at a later date, you can bet your bottom dollar that everyone who had anything to do with the project will be running around looking to absolve themselves of blame and be busy pointing their tainted fingers at others.

It's the moral issue of taking responsibility before rather than after the event that sits at the heart of Francesco Rosi's riveting and oh-so-suggestively titled Hands Over the City [Le mani sulla città]. A property development company controlled by chief investor Edoardo Nottola has secured a contract with the city of Naples to construct new tower blocks as part of its urban renewal programme. His next step is to convince the council to steer the programme onto farmland that he has bought on the cheap for precisely that purpose. It's a no-risk venture, Nottola tells a group of potential moneymen, one that looks set to give them a staggering five thousand per cent return on their investment. But when the side of a building situated adjacent to one of his construction sites suddenly collapses, killing two adults and crippling a child, the mayor is pressurised into launching an inquiry to investigate whether the correct procedures were followed.

Doesn't sound like the basis for dynamite drama, does it? But oh, you should see it. The collapse of the building is an astonishing sequence that was clearly staged for real, and as the locals flee the falling debris, onlookers gather and the emergency services get to work, you could almost believe you were watching a newsreel report of an actual disaster. A couple of minutes later we're in the council chambers and smack in the middle of a furious debate, where impassioned left-winger De Vita is attempting to raise the matter of this architectural catastrophe, a debate the conservative Mayor is keen to suppress. "Councilman De Vita," he shouts across the hubbub, "this item is not on the agenda." "Mr. Mayor, forgive me," De Vita responds, "but people can't schedule their deaths to accommodate our agenda." The protests continue but De Vita is having none of it. This incident and others before it, he tells a packed council chamber, are the direct result of shameful private speculation. He wants an inquiry board set up, one comprised of representatives from every political group, to investigate the city's real estate business, and particularly Edoardo Nottola. He has good reason for targeting the man. Nottola, after all, is not just the majority shareholder in the company whose construction may have caused the collapse, he's a councilman too. The Mayor does not see – or perhaps refuses to acknowledge – the conflict of interest. Councilman Nottola, he brazenly states, is also a private citizen, and there's no law against investing in a construction company, even one that has been given a fat contract by the city. Rarely if ever has political in-fighting and the workings of a city council been so arrestingly portrayed on film. Forget the sneering self-promotion of Prime Minister's Question Time, this is political debate its most furiously passionate, a brilliantly staged and ferociously performed collision of opposing views that at times looks ready to explode into physical conflict.

De Vita eventually gets his way and the requested cross-party inquiry is launched, one that initially fails to uncover any technical wrongdoing but which exposes a moral black hole at the heart of the council. Technically, at least, everyone did their job, but no more than was required, and none of them seem to have spared a thought for the potential human consequences of their actions. It's an attitude memorably illustrated early in the investigation by the planning official who is asked whether the building demolished by Nottola's company shared a common wall with the one that collapsed. In an agitated display of bureaucratic bluff, the man claims to be unable to tell one wall from two on a plan of this scale because of the thickness of the nibs on pens used to make the drawings. "Then how can you establish whether a building can be demolished?" one of the investigating team is quick to ask, to which the official instantly replies, "That's not within my office's jurisdiction." Does any of this sound familiar?

As the inquiry team searches for answers that most of them appear to have no real interest in uncovering, Nottola looks for ways to cover his back. He gets little help from fellow councilman and former ally Maglione, who instead tries to convince him that it would be in the best interests of the party if he took the fall on this one, something a man of Nottola's ambition clearly has no intention of doing. At one point Nottola lays in wait for De Vita and takes him on a tour of his newest apartment block, making a seemingly persuasive case for how the building's modern amenities will improve the lives of those currently living in crumbling slum dwellings. It takes De Vita to point out that those being evicted from the buildings being demolished could never afford to live in the ones that are replacing them.

By the time council elections begin, we're left in little doubt that the majority of councillors are putting their own interests above those of the people they have theoretically been put in office to represent. It's a situation highlighted by inquiry group member Balsamo – a chief hospital doctor and a potential centre party council member – when he gives his reasons for withdrawing his candidacy to his wealthy party leader. "Please don't take this as a betrayal," he tells him calmly, "but I won't be on the same slate as Nottola. Our inquiry reveals half the city's officials should be in jail, and I'm to ignore it and sit next to Nottola on the council?" His leader's response is to tell him to look at the situation in political rather than moral terms. Never mind who Nottola is or what he represents, he suggests, he's a potentially powerful ally, so let's get him on our side so we can form a majority. Balsamo is unimpressed. "How can we guide public opinion if we accept the likes of him?" he asks, to which his colleague tellingly responds, "My dear Balsamo, we create public opinion."

As behind-the-the-scenes machinations involving dark-suited men and quiet conversations see personal grudges put on hold and a deal struck to potentially place Nottola in a position of even greater influence and power, the sense that we're watching the Mafiosi rather than the city council at work is hard to shake off. We're left with the impression that passionate and vocal men like De Vita, who refuse to make deals and who use their position to expose council corruption and wrongdoing in any way they can, are the city's only real hope for change and salvation.

What sells the whole thing as real and makes even the quietest discourse so damned compelling is the carefully selected and universally excellent cast, and I'm not just talking about the lead players here. There is no dead weight under Rosi's direction, with even the smallest role seemingly given the same care and attention as the central characters. This is particularly evident in the animated council debates, where every one of those involved reacts as if taking active part in a real discussion about which they have strongly held views.

But the lead players still shine, notably Carlo Fermariello, who is little short of marvellous as De Vita, so convincing and kinetic in the council chamber scenes that I began seeking him out in even the widest of shots. It thus came as some surprise to me that that Fermariello was not an actor but a real-life Naples councillor of considerable note, and here is essentially playing himself. I'd vote for him in a heartbeat. As his nemesis Nottola, American import Rod Steiger may seem to be slightly handicapped by losing his voice to an Italian dub, but he still delivers in spades as a physical performer. This is memorably highlighted in the scene that immediately follows Maglione's request that Notolla take the fall, a three minute sequence in which the camera follows Steiger as he wanders the room, silently assessing his situation and trying to figure out just what he will do next.

What really hits home is that this story is in no way tied to the time and place in which it was filmed and set. Indeed, I was left with the conviction that the whole thing could be set in modern-day Britain, or indeed any current European country, with only a few cosmetic changes. MPs, both local and national, continue to misuse the system to line their own pockets, favours are done for cronies in business, and public assets are sold off to private companies who put the relentless pursuit of profit over the welfare of the customer and the public good. Fifty years after Hands Over the City was first released, the scandalous and self-serving behaviour it highlights is as virulent as ever, and as politicians with the passion and integrity of De Vita (and Fermariello, of course) seem increasingly consigned to history, there's a sense that it's being given increasingly free reign to do so.

Hands Over the City is European socio-political cinema at its most arresting, and a prime example of how a film constructed largely from verbal exchanges can be as gripping as even the best action-driven thriller. Its continuing relevance prompts admiration for the integrity and vision of director Francesco Rosi, but also a sadness at the realisation that all these years later there are plenty of politicians who still care little for the most vulnerable in society, are still doing dodgy deals to hang on to power, and are still doing favours for wealthy individuals and companies who put profit over people. As I was typing up this review I was even provided with a sobering real-world postscript to personally reflect on, when it was unexpectedly announced that our local international airport looks set to close in the next couple of months so that the owner who bought it for a nominal £1 not six months ago can – you've guessed it – sell off the land for property development.

There's a grittiness to the look of Hands Over the City that prevents the image from popping from the screen in the manner of a high budget Hollywood picture, but I have no problem with that. Several key scenes were shot in what looks like available light using what we can presume was relatively high speed stock, which adds to the film's potent air of realism. Within this constraint this is an excellent transfer, with an impressive level of detail, a rich tonal range and vibrant contrast when the light is right. Black levels are strong, though there are a few scenes where the contrast is a little harsher than it is elsewhere (the sequence where Balsamo visits his party leader is a good example), but this appears to be down to the source material. The image is consistently stable and free of damage and dust spots.

The linear PCM mono track has the expected range restrictions, but is otherwise in sprightly shape, with no trace of damage and little if any background hiss. Dialogue is always clear, a little crisp on the trebles but in a manner that is normal for films of the period. Piero Piccioni's score is rather well served.

Rosi, La Capria, Ciment (15:57)

Francesco Rosi and one of his co-screenwriters and childhood friend Raffaele La Capria are interviewed in French by film critic and historian Michel Ciment. Both men talk about the inspiration for the film, the social and political situation in Italy at the time and their relationship with their home city of Naples, to which they returned as partial outsiders. Ciment makes really interesting points and asks good questions, in the process prompting a range of fascinating and even quotable responses from Rosi and La Capria. Two of my favourites come near the end, when La Capria claims that Rosi's films "aren't made to console viewers but to stimulate them," and Rosi reveals that "I think I allowed myself the enormous luxury of only making films I loved, films in which I could see myself, in which I could seek myself, my identity..." Very cool.

Booklet

The key content here is an excellent essay on the film by Pasquale Iannone that is so in tune with my views that I had to re-write a couple of paragraphs of this review to avoid looking like I was directly ripping him off. The usual stills, credits and notes on viewing are also included.

In case you haven't guessed, I loved every minute of Franceso Rosi's Hands Over the City. Even if you're not gripped by the politics – and you will be – then the urgency of the drama, the richness of the characters and the thrilling sense that we are watching real events unfold still make this consistently compelling viewing. It's a measure of just how easy it is to get hooked that when I loaded the film into VLC to grab some screen shots and the soundtrack was silenced by a technical error, I still ended up watching large chunks of it all over again. A superb transfer given the tone of the source material and a couple of very good extras make this an absolute must-have. Highly recommended.

|